Wheal Eliza Mine

The ruins of the mineworkings | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

Wheal Eliza Mine | |

| Location | Simonsbath |

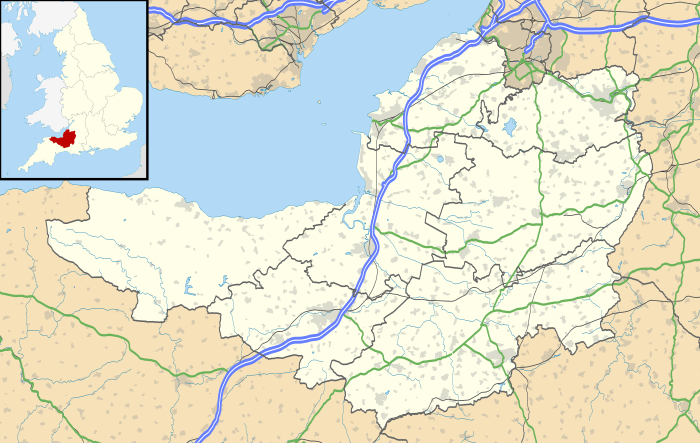

| County | Somerset |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°07′46″N 3°44′19″W / 51.12944°N 3.73861°WCoordinates: 51°07′46″N 3°44′19″W / 51.12944°N 3.73861°W |

| Production | |

| Products | copper, iron |

| History | |

| Opened | 1845 |

| Closed | 1857 |

Wheal Eliza Mine was an unsuccessful copper and iron mine on the River Barle near Simonsbath on Exmoor in the English county of Somerset.

The first mining activity on the site may be from 1552.[1]

The mine was originally called Wheal Maria, then changed to Wheal Eliza.[2] It was one of the projects undertaken by the Knight family after they bought large parts of Exmoor in the early 19th century. Frederick Knight (MP) took over from his father in trying to exploit the mineral assets of the land.[1]

Several adits were driven into the rock and a 300 feet (91 m) shaft dug. It was a copper mine from 1845–54, although no copper was extracted,[2] despite samples showing 60% metallic ore.[3] It was then examined by Henry Schneider, of Schneider Hannay & Co which became the Barrow Hematite Steel Company, during 1856-57 for iron although none was found.[2] The mine was soon abandoned and allowed to flood.[4]

In 1858 the area became notorious for the murder of a seven-year-old girl, Anna Burgess. On the death of her mother she moved with her father, William Burgess, into lodgings in Simonsbath. His older children went into domestic service.[5] Burgess was supported by The Reverend W. H. Thornton (1830-1916) who was the first vicar of Exmoor.[6] The parson raised money to support Burgess, but this was spent on alcohol. In June 1858 he left his lodgings with his daughter, telling the landlady that he was taking her to live with her grandmother in Porlock Weir. Some burnt clothes were found which had belonged to Anna and the Rev Thornton investigated in Porlock Weir finding that the girl had not been taken there. Thornton instigated a search and rode to Curry Rivel to fetch the nearest police officer. The searchers had found a recently dug grave, however it did not contain the girl's body. Burgess had escaped by boat to Swansea but was found and brought back to Somerset, where he was imprisoned in Dulverton. He said nothing about the whereabouts of his daughter and searches of the local moors continued for two months. A witness then said he had seen Burgess near the Wheal Eliza Mine. Local magistrates ordered the mine to be drained which took several months and cost £350. Once the water had been pumped away a bag was found containing the child's body.[4][6] Burgess was found guilty of murder and before being hanged admitted that he had killed her so that he could spend the 2s 6d a week intended for her welfare on drink. He was taken to the gaol in Taunton and hanged on 4 January 1859.[4][5]

Little remains of the original buildings but the pit for the waterwheel and parts of the shaft head with a rising main and pump rod are still at the site.[2][7] There are also platforms and the footings of several buildings.[7]

References

- 1 2 "Wheal Eliza mine, NE of Simonsbath, Exmoor". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Claughton, Peter. "Wheal Eliza.". List of Mines in North Devon and West Somerset. University of Exeter. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ↑ "Will the peat bogs of craggy Exmoor ever reveal their ancient treasures?". North Devon Journal. 10 August 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Byford, Enid (1987). Somerset Curiosities. Dovecote Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0946159483.

- 1 2 "Wheal Eliza" (Word). Victoria County History. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- 1 2 Hesp, Martin. "Simonsbath -Cow Castle Circular". Westcountry Walks. Western Morning News. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- 1 2 "MSO6802 - Wheal Eliza Mine". Exmoor Historic Environment Record. Exmoor National Park. Retrieved 23 March 2014.