Wheat and chessboard problem

The wheat and chessboard problem (sometimes expressed in terms of rice instead of wheat) is a mathematical problem in the form of a word problem:

If a chessboard were to have wheat placed upon each square such that one grain were placed on the first square, two on the second, four on the third, and so on (doubling the number of grains on each subsequent square), how many grains of wheat would be on the chessboard at the finish?

The problem may be solved using simple addition. With 64 squares on a chessboard, if the number of grains doubles on successive squares, then the sum of grains on all 64 squares is: 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + ... and so forth for the 64 squares. The total number of grains equals 18,446,744,073,709,551,615, much higher than what most intuitively expect.

The exercise of working through this problem may be used to explain and demonstrate exponents and the quick growth of exponential and geometric sequences. It can also be used to illustrate sigma notation. When expressed as exponents, the geometric series is: 20 + 21 + 22 + 23 + ... and so forth, up to 263. The base of each exponentiation, "2", expresses the doubling at each square, while the exponents represent the position of each square (0 for the first square, 1 for the second, etc.).

Solutions

The simple, brute-force solution is to just manually double and add each step of the series:

- where is the total number of grains.

The series may be expressed using exponents:

and, represented with capital-sigma notation as:

It can also be solved much more easily using:

A proof of which is:

Multiply each side by 2:

Subtract original series from each side:

Origin and story

The wheat and chess problem appears in different stories about the invention of chess. One of them includes the geometric progression problem. The story is first known to have been recorded in 1256 by Ibn Khallikan.[1] Another version has the inventor of chess (in some tellings Sessa, an ancient Indian Minister) request his ruler give him wheat according to the wheat and chessboard problem. The ruler laughs it off as a meager prize for a brilliant invention, only to have court treasurers report the unexpectedly huge number of wheat grains would outstrip the ruler's resources. Versions differ as to whether the inventor becomes a high-ranking advisor or is executed.[2]

Macdonnell also investigates the earlier development of the theme.[3]

- [According to al-Masudi's early history of India], shatranj, or chess was invented under an Indian king, who expressed his preference for this game over backgammon. [...] The Indians, he adds, also calculated an arithmetical progression with the squares of the chessboard. [...] The early fondness of the Indians for enormous calculations is well known to students of their mathematics, and is exemplified in the writings of the great astronomer Āryabaṭha (born 476 A.D.). [...] An additional argument for the Indian origin of this calculation is supplied by the Arabic name for the square of the chessboard, (بيت, "beit"), 'house'. [...] For this has doubtless a historical connection with its Indian designation koṣṭhāgāra, 'store-house', 'granary' [...].

Pedagogical applications

This exercise can be used to demonstrate how quickly exponential sequences grow, as well as to introduce exponents, zero power, capital-sigma notation and geometric series.

Derivatives of the problem can be used to explain more advanced mathematical topics, such as hexagonal close packing of equal spheres. (How big a chessboard would be required to be able to contain the rice in the last square, assuming perfect spheres of short-grained rice?)

Second half of the chessboard

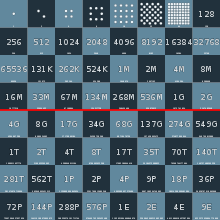

In technology strategy, the second half of the chessboard is a phrase, coined by Ray Kurzweil,[4] in reference to the point where an exponentially growing factor begins to have a significant economic impact on an organization's overall business strategy.

While the number of grains on the first half of the chessboard is large, the amount on the second half is vastly (232 > 4 billion times) larger.

The number of grains of rice on the first half of the chessboard is 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + ... + 2,147,483,648, for a total of 4,294,967,295 (232 − 1) grains of rice, or about 100,000 kg of rice (assuming 25 mg as the mass of one grain of rice).[5] India's annual rice output is about 1,200,000 times that amount.[6]

The number of grains of rice on the second half of the chessboard is 232 + 233 + 234 + ... + 263, for a total of 264 − 232 grains of rice (the square of the number of grains on the first half of the board plus itself). Indeed, as each square contains one grain more than the total of all the squares before it, the first square of the second half alone contains more grains than the entire first half.

On the 64th square of the chessboard alone there would be 263 = 9,223,372,036,854,775,808 grains of rice, or more than two billion times as much as on the first half of the chessboard.

On the entire chessboard there would be 264 − 1 = 18,446,744,073,709,551,615 grains of rice, weighing 461,168,602,000 metric tons, which would be a heap of rice larger than Mount Everest. This is around 1,000 times the global production of rice in 2010 (464,000,000 metric tons).[7]

Moral of the story

The problem warns of the dangers of treating large but finite resources as infinite, i.e., of ignoring distant but absolute and inevitable constraints. As Carl Sagan wrote when referring to the fable, "Exponentials can't go on forever, because they will gobble up everything."[8] Similarly, The Limits to Growth uses the story to present the unintended consequences of exponential growth: "Exponential growth never can go on very long in a finite space with finite resources."[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Clifford A. Pickover (2009), The Math Book: From Pythagoras to the 57th Dimension, New York : Sterling. ISBN 9781402757969. p. 102

- ↑ Tahan, Malba (1993). The Man Who Counted: A Collection of Mathematical Adventures. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. pp. 113–115. ISBN 0393309347. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

- ↑ Macdonell, A. A. (2011-03-15). "Art. XIII.—The Origin and Early History of Chess". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. 30 (01): 117–141. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00146246. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

- ↑ Kurzweil, Ray (1999). The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence. New York: Penguin. p. 37. ISBN 0-670-88217-8. Retrieved 2015-04-06.

- ↑ "Rice CRC - Size and Weight". 2006-08-23. Archived from the original on 2006-08-23. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ "Rice production may touch 100 mn tonnes in 2010-11". Hindustan Times. 2010-07-30. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ↑ "World rice output in 2011 estimated at 476 mn tonnes: FAO". The Economic Times. New Delhi. 2011-06-24. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ↑ Sagan, Carl (1997). Billions and Billions: Thoughts On Life And Death At the Brink Of The Millennium (PDF). New York: Ballantine Books. p. 9. ISBN 0-345-37918-7. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

- ↑ Meadows, Donella H., Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III (1972). The Limits to Growth, p. 24, at Google Books. New York: University Books. ISBN 0-87663-165-0. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

External links

- One telling of the fable

- Salt and chessboard problem - A variation on the wheat and chessboard problem with measurements of each square.