William Barley

William Barley (1565?–1614) was an English bookseller and publisher.[1] He completed an apprenticeship as a draper in 1587, but was soon working in the London book trade. As a freeman of the Drapers' Company, he was embroiled in a dispute between it and the Stationers' Company over the rights of drapers to function as publishers and booksellers. He found himself in legal tangles throughout his life.

Barley's role in Elizabethan music publishing has proved to be a contentious issue among scholars.[2] The assessments of him range from "a man of energy, determination, and ambition",[3] to "somewhat remarkable",[4] to "surely to some extent a rather nefarious figure".[5] His contemporaries harshly criticized the quality of two of the first works of music that he published, but he was also influential in his field.

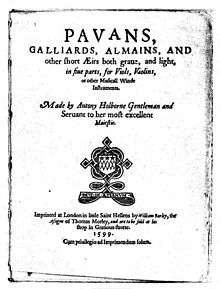

Barley became the assignee of the Thomas Morley, who as well as being a composer held a printing patent (a monopoly of music publishing). He published Anthony Holborne's Pavans, Galliards, Almains (1599), the first work of music for instruments rather than voices to be printed in England. His partnership with Morley enabled him to claim rights to music books, but was short-lived. Morley gave work to the printer Thomas East, and died in 1602. Some publishers ignored Barley's claims, and many music books printed during his later life gave him no recognition.

Drapers' Company

In a deposition of 1598, Barley refers to his age as "xxxiii yeeres or thereabowt", placing his date of birth around 1565.[6] Evidence suggests that Barley may have been born in Warwickshire.[7] Little else is known about his early life. Barley was in London by 1587, having completed an apprenticeship with the Drapers' Company in that year.[8] He trained as a bookseller under Yarath James, a small-time publisher. James operated out of a shop in Newgate Market, near Christ Church Gate, in the 1580s. His interest in ballads was shared by Barley, who published a number of them during his lifetime. By 1592, Barley had opened his own shop in the parish of St Peter upon Cornhill, whose register recorded his marriage to a Mary Harper on 15 June 1603 and christenings and burials of people associated with his family. He conducted business out of this shop for the next twenty years.[9]

Barley is probably the same William Barley who opened a branch office in Oxford. This action brought him into conflict with the authorities. Barley most likely relied on his assistant, William Davis, to run the Oxford shop while he maintained the business at St Peter upon Cornhill. Davis was arrested in 1599 because Barley had failed to register as a bookseller with Oxford University.[10] The two redeemed themselves though, and in 1603, Barley and Davis were admitted as "privileged persons" of Oxford University.[11] Privileged status at Oxford allowed tradesmen to practice their trade free from the jurisdiction of the town's authorities.[12]

Barley ran afoul of London authorities as well. In September 1591, a warrant was issued for his arrest, although the charge is unknown. Barley also found himself in the midst of a longstanding feud between the Drapers' Company and the Stationers' Company. At the time, the latter held a monopoly over the publishing industry; the Drapers' Company wanted its members to be able to function as publishers and booksellers as well, insisting that it was the "custom of the City" to grant its freemen the right to engage in the book trade.[13]

From 1591 to 1604, Barley was associated with at least 57 works. The exact nature of his involvement is, at times, hard to identify. Some works were printed "for" him, others were "to be sold by" him, and two state that they were printed "by" him. He partnered with notable printers and publishers during this period, including Thomas Creede, Abel Jeffes, and John Danter.[14] With Creede, Barley was involved in the publication of A Looking Glass for London and England (1594) and The True Tragedy of Richard III (1594).[15] During this period, Barley entered none of these works in the Stationers' Register (by entering a title into the register, a publisher recorded their rights to the work). This is probably due to the Stationers' feud with the Drapers'; the Stationers' viewed the ability of non-members to enter works into the register as a special privilege. Thus, Barley relied on others, such as Creede, Jeffes, and Danter, to enter these titles. Whether Barley merely acted as a bookseller for the enterers or, in private agreements with them, actually retained the rights to some of the works remains unclear.[16]

In 1595, the Stationers' Company fined Barley 40 shillings for illicitly publishing a number of works. Three years later, the organization sued him and a fellow draper, Simon Stafford, for allegedly publishing privileged books. A raid on Barley's former premises found 4,000 copies of the Accidence, a Latin grammar book protected by monopoly. Despite pleading his innocence in court, Barley, along with Stafford, Edward Venge, and Thomas Pavier (who was Barley's apprentice), was found guilty and sentenced to prison. The lawsuit affirmed the Stationers' Company's control over the Elizabethan book trade. Stafford, Pavier, and other draper-booksellers joined the company within a few years so that they could continue their trade.[17] Curiously, Barley did not join them until 1606. The reasons for the delay are debated among scholars. Bibliographer J. A. Lavin suggests that the Stationers' Company rejected Barley because he had no experience in the printing business.[18] Gerald D. Johnson believes that his partnership with Thomas Morley, who held a royal patent on music publishing, allowed him to circumvent any legal obstacles.[19] The Stationers' Company could not interfere with the publication of works under royal grant.

Music publishing

In Elizabethan England, music printing was regulated by two royal patents issued by the queen: one for metrical psalters (psalms set to music) and one for all other types of music and music paper. The patent-holders thus held a monopoly—only they or their assignees could legally print music.[20] After printer John Day's death in 1584, the patent for metrical psalters transferred to his son Richard Day and was administered by his assignees, who were members of the Stationers' Company. The more general one was awarded to composers Thomas Tallis and William Byrd in January 1575. Despite the monopoly, Tallis and Byrd were not successful in their printing endeavors; their 1575 collection of Latin motets called Cantiones quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur failed to sell and was a financial disaster.[21] After Tallis died in 1585, Byrd continued holding the patent, producing works with his assignee, Thomas East.[22] The monopoly expired in 1596, prompting prospective music publishers such as Barley to take advantage of the resulting power vacuum.[20]

In 1596, despite not having access to a proper music fount, Barley (using the services of Danter and his wood blocks) published The Pathway to Music, a music theory book, and A New Booke of Tabliture, a tutor for the lute and related instruments that included compositions by John Dowland, Philip Rosseter, and Anthony Holborne. Both featured numerous errors, and for the latter, Barley seems not to have gained prior publishing approval from the composers. Dowland disowned A New Booke of Tabliture, calling his lute lessons "falce and unperfect",[23] while Holborne complained of "corrupt coppies" of his work being presented by a "meere stranger".[24] Modern musicologists have labelled the publication "exasperating" and "seedy".[23] Morley criticized The Pathway to Music, stating that the author should be "ashamed of his labour",[23] and that "[v]ix est in toto pagina sana libro" ("there is scarcely a page that makes sense in the whole book").[25] Despite their flaws, both works seem to have been instrumental in introducing music tutor books to the London market.[23]

Two years later, Morley was awarded the same printing monopoly that Byrd had held. Morley's pick of Barley as an assignee (rather than experienced printers such as East or Peter Short, both of whom had previously worked with Morley) is surprising. Morley may have been looking for help in challenging the metrical psalter patent of Richard Day and his assignees. At that time, East and Short were stationers, and the Stationers' Company was actively enforcing the Day monopoly. Barley, however, was not a stationer, and in 1599 he and Morley published The Whole Booke of Psalmes and Richard Allison's Psalmes of David in Metre.[26] The former was a small pocket edition that was largely based on East's 1592 publication of the same name. This work, although pirated and filled with small errors, provides some evidence of Barley's editorial skill; musicologist Robert Illing notes that if Barley "is to be discredited for roguery, he must also be applauded for his strokes of musical imagination" for successfully compressing such a large work into a pocket-sized production.[27] In Allison's work, the two claimed that they had exclusive rights on the metrical psalter. Duly provoked, Day sued. The outcome of his lawsuit is not known, but neither Barley nor Morley ever published another metrical psalter.[26]

Under Morley, Barley published eight books. The covers of each indicated that they were "printed by" Barley, but examination of the typography reveals this to be unlikely. At least two of the works contain designs that seem to belong to a device used by London printer Henry Ballard.[28] Significant among these eight works is Holborne's Pavans, Galliards, Almains (1599), the first work of music for instruments rather than voices to be printed in England, and the first edition of Morley's influential The First Booke of Consort Lessons (1599).[2]

Stationers' Company

Barley's relationship with Morley was short-lived. By 1600, Morley had turned to East as his assignee, authorizing him to print under his name for three years.[29] Two years later, Morley died, and his music patent fell into abeyance. Unable to rely on the protections and privileges of Morley's monopoly, Barley most likely came under increasing pressure from the Stationers' Company. His financial circumstances also deteriorated after he was the target of a successful lawsuit by a cook named George Goodale, who was seeking payment of a debt of 80 pounds. As a result of the suit, many of Barley's goods were seized, including various books and reams of paper. Barley greatly reduced his output from 1601 to 1605, publishing only six works.[30]

Barley evidently decided that it was futile to continue resisting the Stationers' Company, and on 15 May 1605, he successfully petitioned the Drapers' Company for a transfer to the Stationers' Company.[31] On 25 June 1606, the Stationers' Company admitted him as a member. That same day, the Company's court, which had the authority to resolve disputes between members, negotiated a settlement in a lawsuit Barley had brought against East concerning the copyrights on certain music books. East claimed that since he had lawfully entered the books into the Company's register, the rights of the works belonged to him. Barley disagreed, claiming that the works were his through his partnership with Morley, who had held the royal music patent. The court's compromise settlement recognized the rights of both, stipulating that if East were to print an edition of any of the books in question, he was to acknowledge Barley's name on the imprint, pay Barley 20 shillings, and supply him with six free copies. On the other hand, Barley could not publish any of the books without the consent of East or his wife.[32]

Despite the settlement recognizing his claim to Morley's music patent, Barley seemingly found it difficult to enforce his rights, even with his new role as a stationer. Less than half of the known music books published from 1606 to 1613 recognized Barley's rights on the imprint. Barley took Thomas Adams to the Stationers' court in 1609, challenging the copyrights of the music books Adams had published. The court handed down a settlement similar to the one between East and Barley. However, none of the music books Adams published afterward contained any recognition of Barley's patent.[33]

Barley himself published four books under his patent.[34] In March 1612, one of Barley's servants died, possibly from plague. After receiving charitable remuneration from the Stationers' Company, Barley moved, first to the parish of St Katherine Cree, and later to a house on Bishopsgate. Records from St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate indicate his burial on 11 July 1614. His widow, Mary, and their son, William, were legatees of the will of Pavier. Mary Barley, who later remarried, transferred five of her husband's patents to printer John Beale.[35] Some of Barley's remaining copyrights may have also been passed to the printer Thomas Snodham.[2]

Notes

- ↑ Lievsay, among others, believed that Barley was also a printer. This notion was discredited by Lavin in "William Barley, Draper and Stationer" (1969).

- 1 2 3 Miller and Smith

- ↑ Johnson 37

- ↑ McKerrow 20

- ↑ Smith 200

- ↑ Lavin 218

- ↑ Johnson 12. Johnson refutes Lavin's assertion that Barley was born in Woburn, Bedfordshire, claiming that Lavin based his hypothesis on the erroneous assumption that Barley was apprenticed to Thomas Phipps in 1606. By that date, Barley was 41 years old and had already been publishing books for at least 15 years.

- ↑ Lievsay 218

- ↑ Johnson 12. Barley's publications reveal that James' Newgate Market address was also used by Barley in 1591 and 1594.

- ↑ Johnson 12

- ↑ Clark 399. Barley's entry in Oxford's register ("Barley, William; Warw., 35; bibliopola et famulus Doctoris Howson, Vice-Chancellarii") is evidence that he may have been from Warwickshire. Johnson believes that the age discrepancy (Barley should have been 38 in 1603) "is not sufficient to make the identification improbable" (12).

- ↑ Crossley, et al. See also Clark 381–386.

- ↑ Johnson 18. For an in-depth discussion on the dispute between the two companies, see Johnson, Gerald D. (March 1988). "The Stationers Versus the Drapers: Control of the Press in the Late Sixteenth Century". The Library, 6th series 10 (1): 1–17.

- ↑ Johnson 18–19

- ↑ Johnson 41

- ↑ Johnson 18–20

- ↑ Johnson 13–15

- ↑ Lavin 222

- ↑ Johnson 15

- 1 2 Smith 77

- ↑ Milsom

- ↑ Monson

- 1 2 3 4 Johnson 28

- ↑ Smith 86. Smith states that the phrase "meere stranger" is an epithet intended to emphasize Barley's lowly social status.

- ↑ Smith 86

- 1 2 Smith 92–93

- ↑ Illing 223

- ↑ Lavin 217

- ↑ Johnson 30

- ↑ Johnson 15–16

- ↑ Johnson 16

- ↑ Johnson 32

- ↑ Johnson 34–35

- ↑ Johnson 35

- ↑ Johnson 17–18

References

- Clark, Andrew, ed. (1887). Register of the University of Oxford. Volume 2, Oxford: Oxford Historical Society.

- Crossley, Alan, et al. (1979). "Early Modern Oxford" in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 4: The City of Oxford: 74–180. British History Online. Retrieved on 3 June 2009.

- Illing, Robert (1968). "Barley's Pocket Edition of Est's Metrical Psalter". Music and Letters, 49 (3): 219–223.

- Johnson, Gerald D. (March 1989). "William Barley, 'Publisher and Seller of Bookes'". The Library, 6th series 11 (1): 10–46.

- Lavin, J. A. (1969). "William Barley, Draper and Stationer". Studies in Bibliography, 22: 214–23.

- Lievsay, John L. (1956). "William Barley, Elizabethan Printer and Bookseller". Studies in Bibliography, 8: 218–25.

- McKerrow, Ronald (ed., 1910). A dictionary of printers and booksellers in England, Scotland and Ireland, and of foreign printers of English books 1557–1640. London: Bibliographical Society. OCLC 1410091.

- Miller, Miriam and Jeremy L. Smith. "Barley, William" (subscription required). Grove Music Online in Oxford Music Online. Retrieved on 18 December 2008.

- Milsom, John (January 2008). "Tallis, Thomas (c.1505–1585)" (subscription required). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved on 30 December 2008.

- Monson, Craig (January 2008). "Byrd, William (1539x43–1623)" (subscription required). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved on 30 December 2008.

- Smith, Jeremy L. (2003). Thomas East and Music Publishing in Renaissance England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513905-4.

External links