William Cotton (missionary)

| Rev William Charles Cotton | |

|---|---|

Eton College Leaver's Portrait, 1832 | |

| Born |

30 January 1813 Leytonstone, Essex, England |

| Died |

22 June 1879 (aged 66) Chiswick, London, England |

| Cause of death | "ascites and congestion of the brain" |

| Resting place | St John the Baptist's Church, Leytonstone |

| Education | Eton College; Christ Church, Oxford |

| Religion | Anglican |

| Parent(s) | William and Sarah Cotton |

Rev William Charles Cotton MA (30 January 1813 – 22 June 1879) was an Anglican priest, a missionary and an apiarist. After education at Eton College and Christ Church, Oxford he was ordained and travelled to New Zealand as chaplain to George Augustus Selwyn, its first bishop. He introduced the skills of beekeeping to North Island and wrote books on the subject. Later as vicar of Frodsham, Cheshire, England, he restored its church and vicarage but was limited in his activities by mental illness.

Early life

William Charles Cotton was born in Leytonstone, Essex, England, the eldest child of William Cotton and his wife Sarah. His father was a businessman who became Governor of the Bank of England.[1] His younger brother was the jurist Henry Cotton.[2]

He was initially educated at home by tutors, until at the age of 14 he was sent to Eton College. There he became an accomplished rower and had a fine scholastic record, winning the Newcastle Prize for excellence in divinity and the classics in his final year. In 1832 he matriculated to Christ Church, Oxford, and graduated BA in 1836, with first class honours in Classics and second class honours in Mathematics. He decided on a career in the church and was appointed as a curate at Baston, Lincolnshire. However he soon returned to Oxford to work towards his MA. He was ordained as a deacon in 1837 and as a priest in 1839. He had gained his MA in 1838 and in 1839 he was appointed curate at St Edward's Church, Romford, Essex.[3] Even at this stage of his life concerns were being felt about his mental health.[4] He then moved to a curacy at the parish church of St John, Windsor. Here he became a good friend of George Augustus Selwyn, a fellow curate five years his senior.[5]

Missionary

In summer 1841 Selwyn was appointed to be the first Anglican Bishop of New Zealand and Cotton offered to go with him as his chaplain. This decision met with disapproval from Cotton's father who said "You are not missionary material".[6] Cotton did have some of the practical skills which would be valuable; he could use various tools, including a lathe, ride a horse, and row and sail boats.[7] The Tomatin sailed from London for Plymouth Sound without its clerical cargo who went overland to Plymouth before eventually boarding the ship there. Cotton had loaded some hives of bees aboard but had not packed them securely within a hogshead as planned in My Bee Book. Delayed in the English Channel by contrary winds the bee hives were so thrown about aboard the Tomatin that they were jettisoned overboard in Plymouth Sound in Cotton's absence. The missionary party of 23 members set sail from Plymouth late on 26 December 1841 on board the barque Tomatin. On the ship, in addition to their luggage, were various animals and possibly, an unknown number of hives of bees. Cotton's letter dated 30 December 1841, passed to a homeward bound brig on 21 January, stated the bees were safe. However, given the short time available from the Tomatin's arrival in Plymouth Sound on 19 December, the daily hope that contrary winds would abate so they could sail "on the morrow," and the party boarding on 23 December, there's little likelihood he had the time to organize a replacement lot of bees.[8] Either way, the fate of the bees is unknown, they did not survive the trip to Sydney.[9] Also on board was a Māori boy who taught many of the passengers, including Cotton, to speak the Māori language.[10] In April 1842 the Tomatin arrived in Sydney. The boat was damaged by a rock on entering their landing place and, rather than wait for its repair, some of the party, including Selwyn and Cotton, set sail for New Zealand on the brig Bristolian on 19 May. They arrived in Auckland on 30 May. After spending some time as guests of Captain William Hobson, the first Governor of New Zealand, Selwyn and Cotton set sail for the Bay of Islands on the schooner Wave on 12 June, arriving on 20 June.[11] Amongst the party was a clerk, William Bambridge, who was an accomplished artist and was later to become photographer to Queen Victoria.[12]

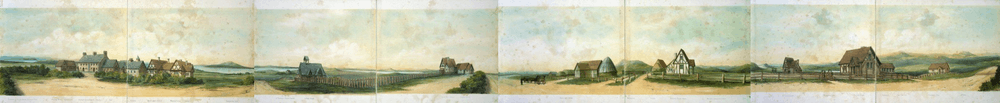

Selwyn had decided to set up residence at the Waimate Mission Station, some 15 miles (24 km) inland from Paihia where the Church Missionary Society had established a settlement 11 years earlier.[13] On 5 July 1842 Selwyn set out on a six-month tour of his diocese leaving the Mission Station in the care of Sarah, his wife, and Cotton. While he was away Cotton was effectively the head of the mission, director of the college and minister at the church.[14] By October 1843 more missionaries had arrived at Waimate and Cotton was able to accompany Bishop Selwyn on his second tour, this time to mission stations and native settlements in the southern part of North Island. Their journey was made partly by canoe but mainly by walking, often for large distances over difficult and dangerous terrain. Part way through the tour Selwyn decided to split the party into two sections with one section led by himself and the other by Cotton. After being away for nearly three months, Cotton arrived back at Waimate early in 1844 and Selwyn returned a few weeks later.[15]

Later in 1844 Selwyn decided to move some 160 miles (257 km) south to Tamaki near Auckland where he bought 450 acres (1.8 km2) of land, giving it the name of Bishop's Auckland. The party left on 23 October and arrived in Auckland on 17 November.[17] During the first six months of 1845 Selwyn was away for much of the time and management of the settlement, and particularly the schools, fell to Cotton.[18] Cotton continued to work in Bishop's Auckland particularly as headmaster of St John's College, and also with ecclesiastical duties and practical tasks. He finally left New Zealand in December 1847, together with Bambridge, arriving in England in May 1848.[19]

Apiarist

From his childhood Cotton had a passionate interest in bees and beekeeping.[2][20] At Oxford University he was a founder and the first secretary of the Oxford Apiarian Society.[2] In 1837 he published his first work about bees, A Short and Simple Letter to Cottagers from a Bee Preserver, which sold 24,000 copies. A second Letter followed three years later. In 1842 he published My Bee Book which amongst other advice suggested ways to render bees semiconscious to obtain the honey rather than by killing them.[21]

New Zealand had two native species of bees but neither was suitable for producing honey. The first honey bees in New Zealand had been introduced by Mary Bumby, the sister of a Wesleyan minister, in March 1839. While Cotton was in Sydney in April 1842 he arranged for hives of bees to be sent to him after his arrival in New Zealand.[22] This took longer than Cotton had expected and it was not until March 1844 that he received his first swarm of honey bees at Waimate. When he moved to Bishop's Auckland he successfully transferred them. He spent much time in training settlers and Māori in the practices of keeping bees and gathering their honey. Towards the end of 1844 he published A Few Simple Rules for New Zealand Beekeepers. He later wrote a series of articles on beekeeping in The New Zealander and these were published together in 1848 as A Manual for New Zealand Beekeepers. Another book, written in Māori, Ko nga pi (The Bees) was published the following year.[23] There is a tradition that Cotton introduced bees to New Zealand[24] but this is incorrect, although he was largely responsible for teaching the skills of beekeeping to the immigrants and the natives.[25]

When Cotton was later appointed vicar of Frodsham he continued his interest in beekeeping and carried out experiments on bees. On one of his trips to the Continent Cotton purchased a copy of a book called Schnurrdiburr by Wilhelm Busch which contained comical illustrated stories about a beekeeper and his bees. Cotton produced his own version of the book with his own verses attached to the illustrations entitled Buzz a Buzz or The Bees – Done freely into English. He took an active part in the discussions which led to the formation of the British Beekeepers' Association and became one of its vice presidents. He collected a library of over 200 books on bees and beekeeping which was bequeathed to the parish of Frodsham on his death. In 1932 it was deposited with the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, and in 1987 transferred to Reading University Library.[26]

Oxford

There is little information about the nine years following Cotton's return from New Zealand. He remained a Fellow of Christ Church, Oxford, but was in residence in the college only intermittently. He spent some of this time travelling on the Continent. In 1855 he was in Constantinople and in the summer of 1857 he visited Avignon and Paris. In December 1855 he was appointed as curate to St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, a position from which he resigned in May 1857. While in Oxford he met Lewis Carroll, with whom he shared an interest in photography.[27]

Vicar of Frodsham

In the summer of 1857 Cotton was appointed vicar of Frodsham, a market town in north Cheshire. At the time there were problems in the parish, in particular there was little financial provision for the outlying townships and the fabric of the parish church of St Laurence was in a bad condition. To make matters worse, the church stood in an elevated position above the town, making access difficult. Cotton sank into a state of apathy and despondence, and in the autumn of 1865 he was admitted for several weeks to Manor House Asylum, Chiswick, an asylum, under the care of Dr Seymour Tuke. There was some improvement in his mental condition and by 1870 Cotton was making arrangements for the restoration of the parish church. At this time there was competition from other denominations, particularly the Wesleyan Methodists. Financed by Thomas Hazlehurst, a member of the family business of Hazlehurst & Sons, soap and alkali manufacturers of nearby Runcorn, one small chapel had already been built near the parish church and another chapel, larger and more splendid, was planned for the centre of town. Cotton organised the building of a temporary chapel of ease in the middle of the town. This was constructed of iron (and known as the Iron Church) and was erected in a very short time on land donated by the Marquess of Cholmondeley. In addition to restoring the parish church, Cotton began to organise the restoration of the vicarage, in autumn 1872 hiring John Douglas to draw up plans. He also employed Douglas to design a house for him to live in while the vicarage was being renovated.[28] Cotton successfully improved the provision of church schools in his parish.[29] During his ministry he took boys from his parish to various events, both locally and to Manchester and Liverpool.[30]

In the late 1870s Cotton's mental health began to deteriorate to such a degree that he became unable to carry out his duties. In 1879 a sequestration order was obtained to allow John Ashton to take charge of the affairs of the parish; Cotton was readmitted to Manor House in the early summer and died there in June. His funeral took place at St John the Baptist's Church in Leytonstone and he was buried in the family grave in the churchyard. On the same day a memorial service was held for him in his Frodsham church.[31] A memorial to his memory is in Frodsham Parish Church.[32] The symbol of the honey bee appears on the chain of office of Frodsham's mayor and in various other places in the town, a Frodsham street is named Maori Drive and a Māori inscription is still present on the doorstep of Cotton's Old Vicarage.[33]

Mental health

There is no doubt that William Cotton was a talented man whose achievements were limited by his mental ill-health. Numerous references have been made to Cotton's erratic behaviour,[34] in particular his over-spending,[35] and his periods of depression.[36] There can be little doubt that he suffered from bipolar disorder; Cotton's biographer Smith refers to his "manic depression".[37] He did achieve much, particularly during his years as a missionary, and in the field of apiculture. As he became older his condition deteriorated, especially during the time he was vicar of Frodsham. However, in view of his achievements in Frodsham, including the building of the Iron Church, the restoration of the parish church and vicarage, and the development of the church schools in his parish, the comment that while he was there "he had occasional periods of effectiveness"[2] seems unfair.

References

Citations

- ↑ Smith 2006, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 Cotton, J. S. (2004), "Cotton, Sir Henry (1821–1892)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 30 March 2013 ((subscription or UK public library membership required))

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 10–14.

- ↑ Smith 2006, p. 14.

- ↑ Smith 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Smith 2006, p. 25.

- ↑ Barrett, Peter (2013) The Immigrant Bees, Volume V (pp.423-429)

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 26–29.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 36–45.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 56–65.

- ↑ "WILLIAM BAMBRIDGE (1819–1879) – Extract from Auckland Waikato Historical Journal No 41, Sep 1982", bambridge.org, retrieved 8 February 2008

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 69, 82–85.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 114–122.

- ↑ Panorama, natlib.govt.nz, retrieved 29 June 2014

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Smith 2006, p. 147.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 155–161.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 7, 9.

- ↑ Smith 2006, p. 18.

- ↑ Smith 2006, p. 88.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 151–154.

- ↑ Latham 1987, p. 49., Smith 2006, p. 7.

- ↑ Barrett, Peter (2009), Myth, Fable and Speculation – W. C. Cotton's attempt to ship bees to New Zealand in 1841, Journal, 39, Frodsham: Frodsham & District History Society, pp. 13–19

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 197–203.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 162–169.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 171–188, 209.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 203–205.

- ↑ Latham 1987, p. 87.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Latham 1987, p. 66.

- ↑ Smith 2006, p. 8.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 20–21, 99, 171, 190–193.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 13–14, 21, 142, 163–164, 193–194.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 14, 20, 162.

- ↑ Smith 2006, p. 208.

Sources

External links

- Works by William Cotton at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Cotton at Internet Archive

- Genealogy page