Wojciech Korfanty

| Wojciech Korfanty | |

|---|---|

|

Wojciech Korfanty in 1925 | |

| Deputy Prime Minister of Poland | |

|

In office October 1923 – December 1923 | |

| Member of the Sejm | |

|

In office 1922–1930 | |

| Member of the Senate | |

|

In office 1930–1935 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Adalbert Korfanty April 20, 1873 Siemianowitz/Laurahütte, German Empire |

| Died |

August 17, 1939 (aged 66) Warsaw, Poland |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Political party |

Polish Christian Democratic Party Labor Party |

| Spouse(s) | Elżbieta Korfantowa |

| Occupation | Politician, activist |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Wojciech Korfanty (born Adalbert Korfanty, IPA: [ˈvɔjt͡ɕɛx kɔɾˈfantɨ]) (20 April 1873 - 17 August 1939) was a Polish activist, journalist and politician, who served as a member of the German parliaments, the Reichstag and the Prussian Landtag, and later, in the Polish Sejm. Briefly, he also was a paramilitary leader, known for organizing the Polish Silesian Uprisings in Upper Silesia, which after World War I was contested by Germany and Poland. Korfanty fought to protect Poles from discrimination and the policies of Germanisation in Upper Silesia before the war and sought to join Silesia to Poland after Poland regained its independence.

Biography

Early life

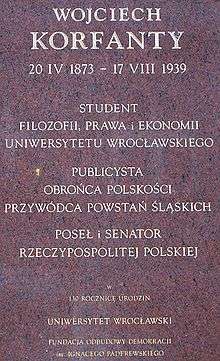

Adalbert Korfanty was born the son of a coal miner in Sadzawka,[1] part of Siemianowice (at the time Laurahütte), in Prussian Silesia, then German Empire. From 1895 until 1901, he studied philosophy, law, and economics, first at the Technical University in Charlottenburg (Berlin) (1895) and then at the University of Breslau,[2] where the Marxist Werner Sombart was among his teachers. Korfanty and Sombart remained friends for many years.

In 1901, Korfanty became editor-in-chief of the Polish language paper Górnoslązak (The Upper Silesian), in which he appealed to the national consciousness of the region's Polish-speaking population.[3]

In 1903, Korfanty was elected to the German Reichstag[4] and in 1904 also to the Prussian Landtag,[5] where he represented the independent "Polish circle" (Polskie koło). This was a significant departure from tradition, as the Polish minority in Germany had so far predominantly supported the conservative 'Centre Party', which represented the large Catholic community in Germany, who felt inferior in the Protestant-dominated Reich.[6] However, when the 'Centre Party' refused to advocate Polish minority rights (beyond the Poles' rights as Catholics), the Poles distanced themselves from it, seeking protection elsewhere. In a paper entitled Precz z Centrum ("Away with the Centre Party", 1901), Korfanty urged the Catholic Polish-speaking minority in Germany to overcome their national indifference and shift their political allegiance from supra-national Catholicism to the cause of the Polish nation.[7] However, Korfanty retained his Christian Democratic convictions and later returned to them in domestic Polish politics.[8]

Polish restoration

At the end of World War I, in 1918, a Kingdom of Poland was proclaimed by Germany, which was then replaced by an independent Polish state. In a Reichstag speech on October 25, 1918, Korfanty demanded that the provinces of West Prussia (including Ermeland (Warmia)) and the city of Danzig (Gdańsk), the Province of Posen, and parts of the provinces of East Prussia (Masuria) and Silesia (Upper Silesia) be included in the Polish state.[9]

After the war, during the Great Poland Uprising, Korfanty became a member of the Naczelna Rada Ludowa (Supreme People's Council) in Poznań, and a member of the Polish provisional parliament, the Constituanta-Sejm.[10] He was also the head of the Polish plebiscite committee in Upper Silesia.[11] He was one of the leaders of the Second Silesian Uprising in 1920[11] and the Third Silesian Uprising in 1921[12] — Polish insurrections against German rule in Upper Silesia. The German authorities were forced to leave their positions by the League of Nations. Poland was allotted by the League of Nations roughly half of the population and valuable mining districts, which were eventually attached to Poland. Korfanty was accused by Germans of organizing terrorism against German civilians of Upper Silesia.[13] German propaganda newspapers also "smeared" him with ordering the murder of Silesian politician Theofil Kupka.[14][15]

Republican politics

Korfanty was a member of the national Sejm from 1922 to 1930, and in the Silesian Sejm (1922–1935), where he represented a Christian Democratic view-point. He opposed the autonomy of the Silesian Voivodship, which he saw as an obstacle against its re-integration into Poland. However, Mr. Korfanty defended the rights of the German minority in Upper Silesia, because he believed that the prosperity of minorities enriched the whole society of a region.

He briefly acted as vice-premier in the government of Wincenty Witos (October–December 1923). From 1924, he resumed his journalist activities as editor-in-chief of the papers Rzeczpospolita ("The Republic", not to be confused with the modern newspaper of the same name) and Polonia.[16] He opposed the May Coup of Józef Piłsudski and the subsequent establishment of Sanacja. In 1930, Korfanty was arrested and imprisoned in the Brest-Litovsk fortress, together with other leaders of the Centrolew, an alliance of left-wing and centrist parties in opposition to the ruling government.[17]

Exile

In 1935, he was forced to leave Poland[18] and emigrated to Czechoslovakia, from where he participated in the "center-right" Morges Front group formed by émigrés Ignacy Paderewski and Władysław Sikorski. After the German invasion of Czechoslovakia, Korfanty moved on to France. He returned to Poland in the April 1939, after Nazi Germany had cancelled the Polish-German non-aggression pact of 1934, hoping that the renewed threat to Polish independence would help overcome the domestic political cleavage. He was arrested immediately upon arrival. In August, he was released as unfit for prison due to his bad health, and died shortly afterwards, two weeks before World War II began with the German invasion of Poland. Although his cause of death remains unclear, it has been claimed that the treatment he received in prison may have caused his health to deteriorate.

Ex Post Facto

After 1945, when the Polish communists sought legitimisation as the champions and guarantors of Polish independence, Korfanty was finally rehabilitated as a national hero due to his fight to protect the Polish population in Upper Silesia from discrimination, and his efforts to join the Polish population in Silesia to Poland. Today, many streets, places and institutions are named after him. When Opole Silesia became part of Poland in 1945, the town of Friedland in Oberschlesien, inside German Upper Silesia, was renamed Korfantów in his honour.

References

- ↑ Rechowicz, Henryk (1971). Sejm Śląski, 1922-1939 (in Polish). Śląsk. p. 340.

- ↑ Plaque (in Polish). Wrocław: Fundacja Odbudowy Democracji im. Ignacego Paderewskiego. 2003 – via WikiMedia Commons.

- ↑ Anderson, Margaret Lavinia (2000). Practicing Democracy: Elections and Political Culture in Imperial Germany. Princeton University Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-691-04854-1.

- ↑ Tooley, T. Hunt (1997). National Identity and Weimar Germany: Upper Silesia and the Eastern Border, 1918-1922. U of Nebraska Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-8032-4429-0.

- ↑ Markert, Werner (1959). Polen. In Zusammenarbeit mit zahlreichen Fachgelehrten (in German). Böhlau Verlag. p. 730.

- ↑ Tägil, Sven (1999). Regions in Central Europe: The Legacy of History. C. Hurst & Co. p. 223. ISBN 1-85065-552-9.

- ↑ Orzechowski, Marian (1975). Wojciech Korfanty: biografia polityczna (in Polish). Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. p. 39.

- ↑ Crampton, R. J. (1997). Eastern Europe in the twentieth century - and after. Routledge. p. 42. ISBN 0-415-16422-2.

- ↑ Weber, Max (1988). Zur Neuordnung Deutschlands: Schriften und Reden 1918-1920. Mohr Siebeck. p. 390. ISBN 3-16-845053-7.

- ↑ Gordon, Harry (1992). The Shadow of Death: The Holocaust in Lithuania. University Press of Kentucky. p. 9. ISBN 0-8131-1729-1.

- 1 2 von Frentz, Christian Raitz (1999). A Lesson Forgotten: Minority Protection Under the League of Nations : the Case of the German Minority in Poland, 1920-1934. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster. p. 76. ISBN 3-8258-4472-2.

- ↑ Halecki, Oskar; Polonsky, Antony (1978). A History of Poland. Routledge. p. 289. ISBN 0-7100-8647-4.

- ↑ Popiołek, Kazimierz; Zieliński, Henryk (1963). Zródla do dziejów powstań śląskich. Zakład Narodowy im. Ossoliń skich. p. 330.

- ↑ T. Hunt Tooley, "National identity and Weimar Germany: Upper Silesia and the eastern border, 1918-1922", U of Nebraska Press, 1997, pg. 227, "But the most vicious attacks were reserved for Korfanty, who was caricatured, smeared and lampooned in every issue. The Polish leader always appeared with money and drink in hand. He appeared cavorting with prostitutes, paying the assassins of Kupka, arriving in hell"

- ↑ Herde, Peter; Kiesewetter, Andreas (2001). Italien und Oberschlesien 1919-1922 (in German). Verlag Königshausen & Neumann. p. 25. ISBN 3-8260-2035-9.

- ↑ Kaiser, Wolfram; Wohnout, Helmut (2004). Political Catholicism in Europe, 1918-45. Routledge. p. 155. ISBN 0-7146-5650-X.

- ↑ von Frentz, Christian Raitz (1999). A Lesson Forgotten: Minority Protection Under the League of Nations : the Case of the German Minority in Poland, 1920-1934. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster. p. 173. ISBN 3-8258-4472-2.

- ↑ Kaiser, Wolfram; Wohnout, Helmut (2004). Political Catholicism in Europe, 1918-45. Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 0-7146-5650-X.

Literature

- Sigmund Karski: Albert (Wojciech) Korfanty. Eine Biographie. Dülmen 1990. ISBN 3-87466-118-0

- Marian Orzechowski: Wojciech Korfanty. Breslau 1975.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wojciech Korfanty. |

- Wojciech Korfanty in the German National Library catalogue

- Biografie

- Die polnischen Aufstände unter Korfanty