List of World Heritage Sites in the United Kingdom and the British Overseas Territories

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Sites are places of importance to cultural or natural heritage as described in the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, established in 1972.[1]

There are 30 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the United Kingdom and the British Overseas Territories.[2] The UNESCO list contains one designated site in both England and Scotland (the Frontiers of the Roman Empire) plus sixteen exclusively in England, five in Scotland, three in Wales, one in Northern Ireland, and one in each of the overseas territories of Bermuda, Gibraltar, the Pitcairn Islands, and Saint Helena. The first sites in the UK to be inscribed on the World Heritage List were Giant's Causeway and Causeway Coast; Durham Castle and Cathedral; Ironbridge Gorge; Studley Royal Park including the Ruins of Fountains Abbey; Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites; and the Castles and Town Walls of King Edward in Gwynedd in 1986. The latest site to be inscribed was the Gorham's Cave complex in Gibraltar in July 2016.[3]

The constitution of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (commonly referred to as UNESCO) was ratified in 1946 by 26 countries, including the UK. Its purpose was to provide for the "conservation and protection of the world’s inheritance of books, works of art and monuments of history and science".[4] The UK contributes £130,000 annually to the World Heritage Fund which finances the preservation of sites in developing countries.[5] Some designated properties contain multiple sites that share a common geographical location or cultural heritage.

The United Kingdom National Commission for UNESCO advises the British government, which is responsible for maintaining its World Heritage Sites, on policies regarding UNESCO.[6] In 2008, Andy Burnham – then Minister for Culture, Media, and Sport – voiced concerns over the worth of the designation of sites in the UK as World Heritage Sites and called for a review of the government's policy of putting forward new sites; this was partly due to rising costs and lower-than-expected income from visitors, few of which were aware of the World Heritage Site status of the sites they visited.[7]

World Heritage Site selection criteria i–vi are culturally related, and selection criteria vii–x are the natural criteria.[8] Twenty-three properties are designated as "cultural", four as "natural", and one as "mixed".[note 1][2] The breakdown of sites by type was similar to the overall proportions; of the 890 sites on the World Heritage List, 77.4% are cultural, 19.8% are natural, and 2.8% are mixed.[9] St Kilda is the only mixed World Heritage Site in the UK. Originally preserved for its natural habitats alone,[10] in 2005 the site was expanded to include the crofting community that once inhabited the archipelago; the site became one of only 25 mixed sites worldwide.[11] The natural sites are the Dorset and East Devon Coast; Giant's Causeway and Causeway Coast; Gough and Inaccessible Islands; and Henderson Island. The rest are cultural.[2]

In 2012, the World Heritage Committee added Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City to the List of World Heritage in Danger citing threats to the site's integrity from planned urban development projects.[12]

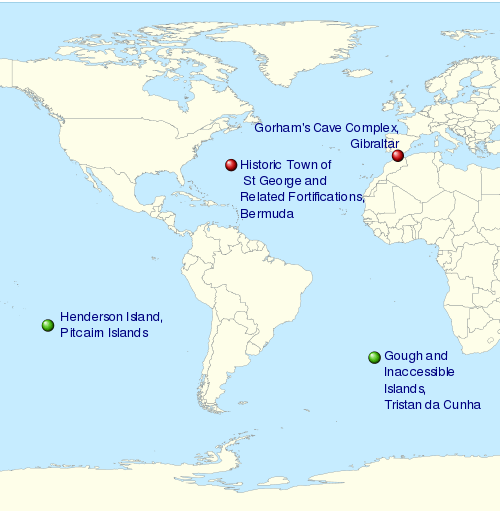

Location of sites

The UNESCO list contains one designated site in both England and Scotland (the Frontiers of the Roman Empire, which is also in Germany)[13] with another sixteen in England, five in Scotland, three in Wales, one in Northern Ireland, and one in each of the overseas territories of Bermuda, Gibraltar, the Pitcairn Islands, and Saint Helena. The maps below show all current World Heritage Sites.

List of sites

The table lists information about each World Heritage Site:

- Name: as listed by the World Heritage Committee[9]

- Location: in one of the UK's constituent countries and overseas territories, with co-ordinates provided by UNESCO

- Period: time period of significance, typically of construction

- UNESCO data: the site's reference number, the year the site was inscribed on the World Heritage List, and the criteria it was listed under

- Description: brief description of the site

| Name | Image | Location | Date | UNESCO data | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blaenavon Industrial Landscape |  |

Blaenavon, 51°47′N 3°05′W / 51.78°N 3.08°W[14] |

19th century[14] | 984; 2000; iii, iv[14] |

In the 19th century, Wales was the world's foremost producer of iron and coal. Blaenavon is an example of the landscape created by the industrial processes associated with the production of these materials. The site includes quarries, public buildings, workers' housing, and a railway.[14] |

| Blenheim Palace |  |

Woodstock, Oxfordshire, 51°50′28″N 1°21′40″W / 51.841°N 1.361°W[15] |

1705–1722[15] | 425; 1987; ii, iv[15] |

Blenheim Palace, the residence of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, was designed by architects John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor. The associated park was landscaped by Capability Brown. The palace celebrated victory over the French and is significant for establishing English Romantic Architecture as a separate entity from French Classical Architecture.[15] |

| Canterbury Cathedral, St Augustine's Abbey, and St Martin's Church |  |

Canterbury, Kent, 51°17′N 1°05′E / 51.28°N 1.08°E[16] |

11th century[16] | 496; 1988; i, ii, vi[16] |

St Martin's Church is the oldest church in England. The church and St Augustine's Abbey were founded during the early stages of the introduction of Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons. The cathedral exhibits Romanesque and Gothic architecture, and is the seat of the Church of England.[16][17][18] |

| Castles and Town Walls of King Edward in Gwynedd |  |

Conwy, Isle of Anglesey and Gwynedd, 53°08′20″N 4°16′34″W / 53.139°N 4.276°W[19] |

13th–14th centuries[19] | 374; 1986; i, iii, iv[19] |

During the reign of Edward I of England (1272–1307), a series of castles were constructed in Wales with the purpose of subduing the population and establishing English colonies in Wales. The World Heritage Site covers many castles including Beaumaris, Caernarfon, Conwy, and Harlech. The castles of Edward I are considered the pinnacle of military architecture by military historians.[19][20] |

| City of Bath |  |

Bath, Somerset, 51°22′48″N 2°21′36″W / 51.380°N 2.360°W[21] |

1st–19th centuries[21] | 428; 1987; i, ii, iv[21] |

Founded by the Romans as a spa, an important centre of the wool industry in the medieval period, and a spa town in the 18th century, Bath has a varied history. The city is preserved for its Roman remains and Palladian architecture.[21] |

| Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape |  |

Cornwall and Devon, 50°08′N 5°23′W / 50.13°N 5.38°W[22] |

18th and 19th centuries[22] | 1,215; 2006; ii, iii, iv[22] |

Tin and copper mining in Devon and Cornwall boomed in the 18th and 19th centuries, and at its peak the area produced two-thirds of the world's copper. The techniques and technology involved in deep mining developed in Devon and Cornwall were used around the world.[22] |

| Derwent Valley Mills |  |

Derwent Valley, Derbyshire, 53°01′12″N 1°29′56″W / 53.020°N 1.499°W[23] |

18th and 19th centuries[23] | 1,030; 2001; ii, iv[23] |

The Derwent Valley Mills was the birthplace of the factory system; the innovations in the valley, including the development of workers' housing – such as at Cromford – and machines such as the water frame, were important in the Industrial Revolution. The Derwent Valley Mills influenced North America and Europe.[24] |

| Dorset and East Devon Coast |  |

Dorset and Devon, 50°42′N 2°59′W / 50.70°N 2.98°W[25] |

n/a | 1029; 2001; viii[25] |

The cliffs that make up the Dorset and Devon coast are an important site for fossils and provide a continuous record of life on land and in the sea in the area since 185 million years ago.[25] |

| Durham Castle and Cathedral |  |

Durham, County Durham, 54°46′26″N 1°34′30″W / 54.774°N 1.575°W[26] |

11th and 12th centuries[26] | 370; 1986; ii, iv, vi[26] |

Durham Cathedral is the "largest and finest" example of Norman architecture in England and vaulting of the cathedral was part of the advent of Gothic architecture. The cathedral houses relics of St Cuthbert and Bede. The Norman castle was the residence of the Durham prince-bishops.[26] |

| Forth Bridge | .jpg) |

Edinburgh, Inchgarvie and Fife, 56°00′02″N 3°23′19″W / 56.000421°N 3.388726°W[27] |

1890 | 1485; 2015; i, iv[27] |

The Forth Bridge is a cantilever railway bridge over the Firth of Forth in the east of Scotland, 9 miles (14 kilometres) west of Edinburgh City Centre. It is considered an iconic structure and a symbol of Scotland, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was designed by the English engineers, Sir John Fowler and Sir Benjamin Baker. |

| Frontiers of the Roman Empire |  |

Northern 54°59′N 2°36′W / 54.99°N 2.60°W[28] |

2nd century[28] | 430; 1987 (modified in 2005 and 2008); ii, iii, iv[28] |

Hadrian's Wall was built in 122 AD and the Antonine Wall was constructed in 142 AD to defend the Roman Empire from "barbarians".[28] The World Heritage Site was previously listed as Hadrian's Wall alone, but was later expanded to include the Antonine Wall in Scotland and the barriers, walls and forts in modern Germany.[29] |

| Giant's Causeway and Causeway Coast |  |

County Antrim, 55°14′24″N 6°30′40″W / 55.240°N 6.511°W[30] |

60–50 million years ago[30] | 369; 1986; vii, viii[30] |

The causeway is made up of 40,000 basalt columns projecting out of the sea. It was created by volcanic activity in the Tertiary period.[30] |

| Gough and Inaccessible Islands |  |

40°19′05″S 9°56′07″W / 40.3181°S 9.9353°W[31] |

n/a | 740; 1995 (modified in 2004); vii, x[31] |

Together, the Gough and Inaccessible Islands preserve an ecosystem almost untouched by mankind, with many endemic species of plants and animals.[31] |

| Heart of Neolithic Orkney |  |

Orkney, 58°59′46″N 3°11′17″W / 58.996°N 3.188°W[32] |

3rd millennium BC[32] | 514; 1999; i, ii, iii, iv[32] |

A collection of Neolithic sites with purposes ranging from occupation to ceremony. It includes the settlement of Skara Brae, the chambered tomb of Maes Howe and the stone circles of Stenness and Brodgar.[32] |

| Henderson Island | |

Henderson Island, 24°21′S 128°19′W / 24.35°S 128.31°W[33] |

n/a | 487; 1988; vii, x[33] |

The island is an atoll in the south of the Pacific Ocean, the ecology of which has been almost untouched by man and its isolation illustrates the dynamics of evolution. There are ten plant and four animal species endemic to the island.[33] |

| Historic Town of St George and Related Fortifications, Bermuda |  |

St George, 32°22′46″N 64°40′40″W / 32.379444°N 64.677778°W[34] |

17th–20th centuries[34] | 983; 2000; iv[34] |

Founded in 1612, St George's is the oldest English town in the New World and an example of planned urban settlements established in the New World in the 17th century by colonial powers. The fortifications illustrate defensive techniques developed through the 17th to 20th centuries.[34] |

| Ironbridge Gorge | |

Ironbridge, Shropshire, 52°37′34″N 2°29′10″W / 52.626°N 2.486°W[35] |

18th century[35] | 371; 1986; i, ii, iv, vi[35] |

Ironbridge Gorge contains mines, factories, workers' housing, and the transport infrastructure that was created in the gorge during the Industrial Revolution. The development of coke production in the area helped start the Industrial Revolution. The Iron Bridge was the world's first bridge built from iron and was architecturally and technologically influential.[35] |

| Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City |

|

Liverpool, Merseyside, 53°24′N 2°59′W / 53.40°N 2.99°W[36] |

18th and 19th centuries[36] | 1,150; 2004; ii, iii, iv[36] |

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Liverpool was one of the largest ports in the world. Its global connections helped sustain the British Empire, and it was a major port involved in the slave trade until its abolition in 1807, and a departure point for emigrants to North America. The docks were the site of innovations in construction and dock management.[36] |

| Maritime Greenwich |  |

Greenwich, London, Greater London, 51°28′45″N 0°00′00″E / 51.4791°N 0°E[37] |

17th and 18th centuries[37] | 795; 1997; i, ii, iv, vi[37] |

As well as the presence of the first example of Palladian architecture in England, and works by Christopher Wren and Inigo Jones, the area is significant for the Royal Observatory where the understanding of astronomy and navigation were developed.[37] |

| New Lanark |  |

New Lanark, South Lanarkshire, 55°40′N 3°47′W / 55.66°N 3.78°W[38] |

19th century[38] | 429; 2001; ii, iv, vi[38] |

Prompted by Richard Arkwright's factory system developed in the Derwent Valley, the community of New Lanark was created to provide housing for workers at the mills. Philanthropist Robert Owen bought the site and turned it into a model community, providing public facilities, education, and supporting factory reform.[38] |

| Old and New Towns of Edinburgh |  |

Edinburgh, 55°56′49″N 3°11′28″W / 55.947°N 3.191°W[39] |

11th–19th centuries[39] | 728; 1995; ii, iv[39] |

The Old Town of Edinburgh was founded in the Middle Ages, and the New Town was developed in 1767–1890. It contrasts the layout of settlements in the medieval and modern periods. The layout and architecture of the new town, designed by luminaries such as William Chambers and William Playfair, influenced European urban design in the 18th and 19th centuries.[39] |

| Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret's Church |  |

Westminster, Greater London, 51°29′59″N 0°07′43″W / 51.4997°N 0.1286°W[40] |

10th, 11th, and 19th centuries[40] | 426; 1987 (modified in 2008); i, ii, iv[40] |

The site has been involved in the administration of England since the 11th century, and later the United Kingdom. Since the coronation of William the Conqueror, all English and British monarchs have been crowned at Westminster Abbey. Westminster Palace, home to the British Parliament, is an example of Gothic Revival architecture; St Margaret's Church is the palace's parish church, and although it pre-dates the palace and was built in the 11th century, it has been rebuilt since.[40][41][42] |

| Pontcysyllte Aqueduct and Canal |  |

Trevor, Wrexham, 52°58′12″N 3°05′13″W / 52.970°N 3.087°W[43] |

1795–1805[43] | 1,303; 2009; i, ii, iv[43] |

The aqueduct was built to carry the Ellesmere Canal over the Dee Valley. Completed during the Industrial Revolution and designed by Thomas Telford, the aqueduct made innovative use of cast and wrought iron, influencing civil engineering across the world.[43][44] |

| Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew |  |

Kew, Greater London, 51°28′26″N 0°17′42″W / 51.474°N 0.295°W[45] |

18th–20th centuries[45] | 1,084; 2003; ii, iii, iv[45] |

Created in 1759, the influential Kew Gardens were designed by Charles Bridgeman, William Kent, Capability Brown, and William Chambers. The gardens were used to study botany and ecology and furthered the understanding of the subjects.[45] |

| St Kilda |  |

St Kilda, 57°48′58″N 8°34′59″W / 57.816°N 8.583°W[46] |

n/a | 387; 1987 (modified in 2005 and 2008); ii, iii, iv[46] |

Although inhabited for over 2,000 years, the isolated archipelago of St Kilda has had no permanent residents since 1930. The islands' human heritage includes various unique architectural features from the historic and prehistoric periods. St Kilda is also a breeding ground for many important seabird species including the world's largest colony of gannets and up to 136,000 pairs of puffins.[46][47] |

| Saltaire |  |

Saltaire, Shipley, West Yorkshire, 53°50′13″N 1°47′24″W / 53.837°N 1.790°W[48] |

1853[48] | 1,028; 2001; ii, iv[48] |

Saltaire was founded by mill-owner Titus Salt as a model village for his workers. The site, which includes the Salts Mill, featured public buildings for the inhabitants and was an example of 19th-century paternalism.[48] |

| Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites |  |

Wiltshire, 51°10′44″N 1°49′31″W / 51.1788°N 1.8252°W[49] |

4th–2nd millennia BC[49] | 373; 1986 (modified in 2008); i, ii, iii[49] |

The Neolithic sites of Avebury and Stonehenge are two of the largest and most famous megalithic monuments in the world. They relate to man's interaction with his environment. The purpose of the henges has been a source of speculation, with suggestions ranging from ceremonial to interpreting the cosmos. "Associated sites" includes Silbury Hill, Beckhampton Avenue, and West Kennet Avenue.[49] |

| Studley Royal Park including the Ruins of Fountains Abbey |  |

North Yorkshire, 54°06′58″N 1°34′23″W / 54.116°N 1.573°W[50] |

1132 (abbey), 19th century (park)[50] |

372; 1986; i, iv[50] |

Before the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the mid-16th century, Fountains Abbey was one of the largest and richest Cistercian abbeys in Britain and is one of only a few that survives from the 12th century. The later garden, which incorporates the abbey, survives to a large extent in its original design and influenced garden design in Europe.[50] |

| Tower of London |  |

Tower Hamlets, Greater London, 51°30′29″N 0°04′34″W / 51.5080°N 0.0761°W[51] |

11th century[51] | 488; 1988; ii, iv[51] |

Begun by William the Conqueror in 1066 during the Norman conquest of England, the Tower of London is a symbol of power and an example of Norman military architecture that spread across England. Additions by Henry III and Edward I in the 13th century made the castle one of the most influential buildings of its kind in England.[51] |

| Gorham's Cave Complex |  |

East face of the Rock of Gibraltar, 36°07′13″N 5°20′31″W / 36.120397°N 5.342075°W[52] |

33-23 thousand years ago[53] | 1500; 2016; iii[52] |

Comprising four natural sea caves, the complex is the last known site of Neanderthal inhabitation some 28,000 years ago. Evidences of occupation by modern humans are also present at the site.[52] |

Tentative list

The Tentative List is an inventory of important heritage and natural sites that a country is considering for inscription on the World Heritage List, thereby becoming World Heritage Sites. The Tentative List can be updated at any time, but inclusion on the list is a prerequisite to being considered for inscription within a five- to ten-year period.[54]

The UK's Tentative List was last updated on 16 July 2016, and consisted of 12 sites. The properties on the Tentative List are as follows:[55]

See also

- List of World Heritage Sites in Europe

- World Heritage Sites in Scotland

- Tourism in the United Kingdom

Notes

- ↑ A mixed site is one that falls under both natural and cultural criteria.

References

- Citations

- ↑ "The World Heritage Convention". UNESCO. Retrieved September 17, 2010.

- 1 2 3 United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Properties inscribed on the World Heritage List, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-08-16

- ↑ Forth Bridge given World Heritage Site status, BBC Online, 2015-07-05, retrieved 2015-07-06

- ↑ UNESCO Constitution, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-08-17

- ↑ Funding, Department for Culture, Media and Sport, retrieved 2009-08-17

- ↑ About us, The United Kingdom National Commission for UNESCO, retrieved 2009-08-17

- ↑ Andy Burnham launches debate on the future designation of World Heritage Sites in the UK, Department for Culture, Media and Sport, 2008-12-02, retrieved 2009-08-17

- ↑ The Criteria for Selection, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-27

- 1 2 World Heritage List, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-27

- ↑ New publication spotlights St Kilda, Scottish Natural Heritage, 2004-12-09, retrieved 2009-08-16

- ↑ Dual World Heritage Status For Unique Scottish Islands, National Trust for Scotland, 2005-07-14, retrieved 2009-08-16

- ↑ "Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City Threats to the Site (2012)". Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ↑ "Frontiers of the Roman Empire". unesco.org.

- 1 2 3 4 Blenheim Palace, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-27

- 1 2 3 4 Canterbury Cathedral, St Augustine's Abbey, and St Martin's Church, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-08-15

- ↑ Historic England, "Church of St Martin (441523)", Images of England, retrieved 2009-08-16

- ↑ Historic England, "St Augustine's Abbey (464466)", PastScape, retrieved 2009-08-16

- 1 2 3 4 Castles and Town Walls of King Edward in Gwynedd, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-08-12

- ↑ Liddiard (2005), p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 City of Bath, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-29

- 1 2 3 4 Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-08-12

- 1 2 3 Derwent Valley Mills, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-27

- ↑ Derwent Valley Mills Partnership (2000), pp. 30–31, 96.

- 1 2 3 Dorset and East Devon Coast, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-29

- 1 2 3 4 Durham Castle and Cathedral, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-27

- 1 2 Forth Bridge, UNESCO, retrieved 2015-07-05

- 1 2 3 4 Frontiers of the Roman Empire, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-28

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Frontiers of the Roman Empire". Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Giant's Causeway and Causeway Coast, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-28

- 1 2 3 Gough and Inaccessible Island, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-08-12

- 1 2 3 4 Heart of Neolithic Orkney, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-28

- 1 2 3 Henderson Island, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-28

- 1 2 3 4 Historic Town of St George and Related Fortifications, Bermuda, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-08-02

- 1 2 3 4 Ironbridge Gorge, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-27

- 1 2 3 4 Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-29

- 1 2 3 4 Maritime Greenwich, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-29

- 1 2 3 4 New Lanark, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-28

- 1 2 3 4 Old and New Towns of Edinburgh, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-08-12

- 1 2 3 4 Westminster Palace, Westminster Abbey and Saint Margaret's Church, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-08-15

- ↑ History, Westminster Abbey, retrieved 2009-08-15

- ↑ Thornbury (1878), p. 567.

- 1 2 3 4 Pontcysyllte Aqueduct and Canal, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-08-12

- ↑ Listed Buildings: Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, Trevor, Wrexham County Borough Council, retrieved 2009-08-12

- 1 2 3 4 Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-28

- 1 2 3 St Kilda, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-08-12

- ↑ Benvie (2000).

- 1 2 3 4 Saltaire, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-28

- 1 2 3 4 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-27

- 1 2 3 4 Studley Royal Park including the Ruins of Fountains Abbey, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-29

- 1 2 3 4 Tower of London, UNESCO, retrieved 2009-07-28

- 1 2 3 Gorham's Cave Complex, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-15

- ↑ Finlayson C, Pacheco FG, Rodríguez-Vidal J, et al. (October 2006). "Late survival of Neanderthals at the southernmost extreme of Europe" (PDF). Nature. 443 (7113): 850–3. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..850F. doi:10.1038/nature05195. PMID 16971951.

- ↑ Glossary, UNESCO, retrieved 2010-01-01

- ↑ Tentative list of United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, UNESCO, 2006-01-19, retrieved 2016-07-16

- 1 2 3 Chatham Dockyard and its Defences, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-17

- 1 2 3 Creswell Crags, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-17

- 1 2 3 Darwin's Landscape Laboratory, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-17

- 1 2 England's Lake District, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-17

- 1 2 Island of St Helena, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-17

- 1 2 3 Jodrell Bank Observatory, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-17

- 1 2 Mousa, Old Scatness and Jarlshof: the Zenith of Iron Age Shetland, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-17

- 1 2 Slate Industry of North Wales, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-17

- 1 2 Flow Country, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-17

- 1 2 The Twin Monastery of Wearmouth Jarrow, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-17

- 1 2 Turks and Caicos Islands, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-17

- 1 2 Great Spas of Europe, UNESCO, retrieved 2016-07-17

- Bibliography

- Benvie, Neil (2000), Scotland's Wildlife, London: Aurum Press, ISBN 978-1-85410-978-1

- Derwent Valley Mills Partnership (2000), Nomination of the Derwent Valley Mills for inscription on the World Heritage List, Derwent Valley Mills Partnership

- Keay, J; Keay, J (1994), Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland, London: Harper Collins, ISBN 0-00-255082-2

- Liddiard, Robert (2005), Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500, Macclesfield: Windgather Press Ltd, ISBN 0-9545575-2-2

- Thornbury, Walter (1878), "St Margaret's Westminster", Old and New London, Victoria County History, 3

External links