Woylie

| Woylie[1] | |

|---|---|

1.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Potoroidae |

| Genus: | Bettongia |

| Species: | B. ogilbyi |

| Binomial name | |

| Bettongia penicillata Gray, 1837 | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

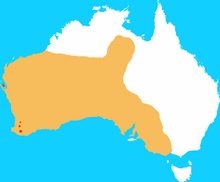

| Historic woylie range in orange, current range in red | |

The woylie (Bettongia ogilbyi), also known as the brush-tailed bettong, is an extremely rare small marsupial that belongs to the genus Bettongia. It is endemic to Australia. Formerly it had two separate subspecies, B. p. ogilbyi and the now extinct B. p. penicillata.

Etymology

The common name is from the Nyungar language walyu.[3]

Description

The woylie is a small macropod, being only some 30 to 35 cm in body length, with a tail around 37 cm long, and weighing between 1.1 and 1.6 kg.[4] The fur of this bettong is yellowish-brown in color with a patch of paler fur on its belly, while the end of its furry tail is dark colored. It has little or no hair on the muzzle and tail. This species has a more slender build and larger ears than its relative the burrowing bettong.[5][6][7]

Distribution and habitat

The woylie once inhabited more than 60% of the Australian mainland, but now occurs on less than 1%. It formerly ranged over all of the southwest of Eastern Australia, most of South Australia, the northwest corner of Victoria and across the central portion of New South Wales. It was abundant in the mid-19th century. By the 1920s, it was extinct over much of its range. As of 1992, it was reported only from four small areas in Western Australia. In South Australia, a number of populations have been established through reintroduction of captive-bred animals. As of 1996, it occurred in six sites in Western Australia, including Karakamia Sanctuary run by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, and on three islands and two mainland sites in South Australia, following the reintroduction program and the controlling of foxes. Today, this species lives mostly in open sclerophyll forest and Malee eucalyptus woodlands with a dense low understory of tussock grasses.[5] However, this versatile species is also known to have once inhabited a wide range of habitats, including low arid scrub or desert spinifex grasslands.[2][8]

Ecology and behaviour

This species is strictly nocturnal and is not gregarious. It can breed all year round if the conditions are favorable. The female can breed at six months of age and give birth every 3.5 months. Its lifespan in the wild is about four to six years.[5] The woylie is able to use its tail, curled around in a prehensile manner, to carry bundles of nesting material. It builds its dome-shaped nest in a shallow scrape under a bush. The nest, which consists of grass and shredded bark, sticks, leaves, and other available material, is well-made and hidden. The woylie rests in its nest during the day and emerges at night to feed.

The woylie has an unusual diet for a mammal. Although it may eat bulbs, tubers, seeds, insects, and resin of the hakea plant, the bulk of its nutrients are derived from underground fungi which it digs out with its strong foreclaws. These fungi can only be digested indirectly. In a portion of its stomach, the fungi are consumed by bacteria. These bacteria produce the nutrients that are digested in the rest of the stomach and small intestine. When it was widespread and abundant, the woylie likely played an important role in the dispersal of fungal spores within desert ecosystems.[8]

Population and current status

This bettong was once very abundant and widespread across Australia. In 1863, Gould mentioned it was "abundant in all parts of the colony". As late as 1910, the species was said to be very abundant in the Australian southwest.[7] Decline seems to have been caused by a number of factors, including the impact of introduced grazing animals, land clearance for agriculture, predation by introduced red foxes[9] and, possibly, changed fire regimens. As a result, this species suffered localized extinctions throughout its range, and was very endangered by the 1970s.

Subsequent conservation efforts concentrated on controlling the introduced red fox and reintroducing woylies from expanding populations to fox-free sites in its former range. Stable populations have been established in places such as Venus Bay, St Peter Island, Wedge Island, Shark Bay, and Scotia Sanctuary. As a result of these efforts, the woylie population rose to sufficient numbers that it was taken off the threatened species list in 1996. The population expanded with new, wild-born joeys being recorded and survived several drought years in the early 2000s. The total population of this species rose to 40,000 in 2001.

However, sudden population crash occurred in late 2001, and in just five years in most areas, the woylie population dropped to only 10-30% of its pre-2001 numbers. The IUCN Red List also revised the woylie as critically endangered.

The exact cause of this rapid population crash remains uncertain, although researcher Andrew Thompson has found two parasite infestations in woylie blood.[10] Predation and habitat destruction were also suggested as contributing to the recent decline of the species.[11]

As of 2011, the global population is estimated to be less than 5,600 individuals.[2] It is said to be "on the brink of extinction."[12]

"It is believed the woylie population peaked a decade ago at more than 250,000, but numbers have since declined by about 90 per cent."[13] However, despite these losses woylies continue to thrive as small localized populations in fox- and cat-free sanctuaries, including a population at Wadderin Sanctuary in the central Western Australian wheatbelt established in 2010.

References

- ↑ Groves, C.P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 57. OCLC 62265494. ISBN 0-801-88221-4.

- 1 2 3 Wayne, A.; Friend, T.; Burbidge, A.; Morris, K. & van Weenen, J. (2008). "Bettongia penicillata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 29 December 2008. Database entry includes justification for why this species is listed as critically endangered

- ↑ "Aboriginal Words in the English Language: L-Z". One Big Garden. Retrieved 12 Sep 2012.

- ↑ "Brush-tailed bettong (Bettongia penicillata)". ARKive.

- 1 2 3 "Woylie (Bettongia penicillata)". Shark Bay World Heritage Area. Government of Western Australia - Department of Parks and Wildlife.

- ↑ "Lesser Bilby Macrotis leucura" (PDF). Threatened species of the Northern Territory. Northern Territory Government - Department of Land Resource Management. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- 1 2 Francis Harper (1945). Extinct and Vanishing Mammals of the Old World.

- 1 2 "Brush-tailed Bettong Woylie Bettongia penicillata" (PDF). Threatened species of the Northern Territory. Northern Territory Government - Department of Land Resource Management. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ↑ Short, J. (1998). "The extinction of rat-kangaroos (Marsupialia: Potoroidae) in New South Wales, Australia". Biological Conservation. 86: 365–377. doi:10.1016/s0006-3207(98)00026-3.

- ↑ Leonie Harris (2008-10-07). "Woylie marsupial under threat". 7.30 report.

- ↑ "Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi - Woylie". Australian Government - Department of the Environment.

- ↑ Roger Underwood, Doomed Planet: On the origin of the specious, Quadrant, August 31, 2012

- ↑ "Win for endangered woylie efforts." June 23, 2014. News.com.au at

General references