Yolo Causeway

| Yolo Causeway | |

|---|---|

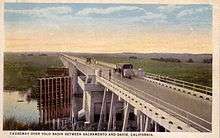

An artist's representation of the original Yolo Causeway. Circa 1920. | |

| Coordinates | 38°33′49″N 121°38′18″W / 38.563494°N 121.638392°WCoordinates: 38°33′49″N 121°38′18″W / 38.563494°N 121.638392°W |

| Carries |

6 lanes of pedestrians and bicycles |

| Crosses | Yolo Bypass |

| Locale | Yolo County, California |

| Official name | Blecher-Freeman Memorial Causeway |

| Maintained by | Caltrans |

| NBI | 22 0044 & 22 0045 |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | prestressed concrete tee beam |

| Total length | 3.2 miles (5.1 km), divided into 877.8-metre (2,880 ft) western segment and 2,682.2-metre (8,800 ft) eastern segment |

| Width | 35.7 metres (117 ft) |

| Number of spans |

72 (western segment) 127 (eastern segment) |

| History | |

| Opened | 1916 (original), 1962 (current) |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 150,000 (2010) |

Yolo Causeway Location in Northern California | |

The Yolo Causeway is a 3.2-mile (5.2-kilometer) long elevated highway viaduct on Interstate 80 that crosses the Yolo Bypass floodplain and connects the cities of West Sacramento, California and Davis, California.

History

Before a causeway was built, motor travelers between Davis and Sacramento were forced to detour south through Tracy and Stockton when seasonal flooding left the Yolo Bypass basin under water.[1] Once the ground was sufficiently dry enough to support vehicle traffic, the first vehicle to make it across the Yolo Bypass established the seasonal "Tule Jake" Road, which was typically passable only during the summer months.[2]

1916 causeway

The original Yolo Causeway opened on 18 March 1916[3] as a two-lane structure 21 feet (6.4 m) wide and 16,538 feet (5,041 m) long,[1][4] connecting what is now the city of West Sacramento with Davis, California. Initially, the causeway was composed of a 2,470-foot (750 m) timber trestle section on the west and the remainder concrete trestle section, with a 113-foot (34 m) plate girder bascule span, which was opened to permit passage of levee maintenance barges.[4] The causeway width was doubled in 1933 when a new all-timber viaduct was added just south of the 1916 reinforced concrete structure, and lights were added in 1950.[1]

Initially, the Lincoln Highway association declined to shift the route to take advantage of the Yolo Causeway,[5] but in 1928, following the completion of the Carquinez Bridge, it was made a part of the re-routed Lincoln Highway, the first road across America. Later, the causeway became a part of US Highways 40 and 99W.

1962 causeway

The current causeway was built in 1962.[3] From west to east, the causeway is composed of twinned 2,880-foot (880 m) long concrete trestles, a 4,700-foot (1,400 m) long earth fill segment, and twinned 8,800-foot (2,700 m) long concrete trestles. The easternmost of the two bridges is the longer of the two and traffic reporters will sometimes refer to the two structures as the "long bridge" and the "short bridge". Each trestle carries a 46-foot (14 m) wide, three-lane roadway.

It was renamed the "Blecher-Freeman Memorial Causeway" in 1994,[6] after two California Highway Patrol officers who were shot to death in 1978 after a highway stop near the causeway.[7]

Bypass

The 25,500 acre (103 km²) Yolo Bypass protects Sacramento and other California Central Valley communities from flooding. During wet seasons, it can be full of water. It contains the Vic Fazio Yolo Wildlife Area, the largest ecological restoration project west of the Everglades. Other nature preserves in it include the Fremont Weir Wildlife Area and Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area.

Approximately 250,000 Mexican free-tailed bats migrate to the Yolo Causeway every June. They roost in the expansion joints between the causeway segments, and feed on the insects that live in the wetlands formed by the Yolo Bypass.[8]

UC Davis vs. Sacramento State

The Causeway Classic College football game between the University of California, Davis and California State University, Sacramento and the Causeway Carriage trophy awarded to the winner of that game are both named after the Yolo Causeway.

References

- 1 2 3 Meyer, J.G.; Hart, Alan S. (September–October 1961). "Progress on US 40 – Carquinez to Sacramento" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. California Department of Transportation. 40 (9–10): 6–10. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "There's No Way to Get There From Here" (PDF). The Traveler. Lincoln Highway Association – California Chapter. 13 (3). July 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- 1 2 Colley, R.F.; Chapman, M. (May–June 1962). "Yolo Causeway: New Crossing Is Scheduled for Early 1963 Completion" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. California Department of Transportation. 41 (5–6): 44–49. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- 1 2 Sutton, W.E. (June 1940). "Redecking the Yolo Causeway" (PDF). California Highways and Public Works. California Department of Transportation. 18 (6): 16; 32. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "Causeway Not On Lincoln Highway". The Lodi Sentinel. 17 June 1916.

- ↑ Assembly Concurrent Resolution No. 119, Act No. ACR 119 of 11 April 1994 (in English). Retrieved on 2 August 2015.

- ↑ Faigin, Daniel. "California Highways - Interstate 80". Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ↑ Costabile, Dominick (12 August 2012). "Going batty: Migrants roost under causeway". Davis Enterprise. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yolo Causeway. |

External links

- Yolo Causeway - Davis Wiki

- Caltrans timeline

- CHP Memorial: Blecher-Freeman

- Blow, Ben (1920). "XI. Division III – The building of the Sacramento-Yolo Causeway". California highways: a descriptive record of road development by the state and by such counties as have paved highways. San Francisco: H.S. Crocker Co. pp. 71–75. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- "The Yolo Basin Concrete Trestle". The Architect and Engineer. 47 (1): 97–100. October 1916. Retrieved 2 August 2015.