Zavala County, Texas

| Zavala County, Texas | |

|---|---|

|

Zavala County Courthouse in Crystal City | |

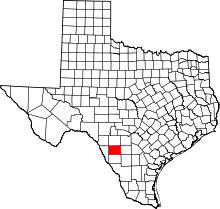

Location in the U.S. state of Texas | |

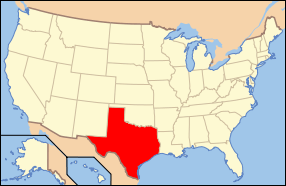

Texas's location in the U.S. | |

| Founded | 1884 |

| Named for | Lorenzo de Zavala |

| Seat | Crystal City |

| Largest city | Crystal City |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,302 sq mi (3,372 km2) |

| • Land | 1,297 sq mi (3,359 km2) |

| • Water | 4.3 sq mi (11 km2), 0.3% |

| Population | |

| • (2010) | 11,677 |

| • Density | 9.0/sq mi (3/km²) |

| Congressional district | 23rd |

| Time zone | Central: UTC-6/-5 |

| Website |

www |

Zavala County is a county located in the U.S. state of Texas. As of the 2010 census, the population was 11,677.[1] Its county seat is Crystal City.[2] The county was created in 1858 and later organized in 1884.[3] Zavala is named for Lorenzo de Zavala, Mexican politician, signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence, and first vice president of the Republic of Texas.

History

Native Americans

Radiocarbon assays indicate the county’s Tortuga Flat Site[4] was used in the 15th and 16th centuries by Pacuache.[5] Archeologist T. C. Hill of Crystal City conducted excavations in 1972-1973 at the site, uncovering artifacts. More than 100 archeological sites have been identified by researchers of the University of Texas at San Antonio at the Chaparrosa Ranch. Coahuiltecan, Tonkawa, Lipan Apache and Mescalero Apache and Comanche have inhabited the area after the Pacuache.[6]

The Wild Horse Desert

The area between the Rio Grande and the Nueces River, which included Zavala County, became disputed territory known as the Wild Horse Desert, where neither the Republic of Texas nor the Mexican government had clear control. Ownership was in dispute until the Mexican-American War. The area became filled with lawless characters who deterred settlers in the area. An agreement signed between Mexico and the United States in the 1930s put the liability of payments to the descendants of the original land grants on Mexico.[7][8] According to a list of Spanish and Mexican grants in Texas (found in the Book, "With All Arms," by Carl Laurence Duaine, New Santander Press, Edinberg, TX, 1987), Pedro Aguirre owned 51,296 acres in Zavala County, while Antonio Aguirre had 34,552. Seven other people (including two women—Juana Fuentes and Maria Escolastica Diaz—each had 4,650 acres.

County established and growth

Zavala County was established in 1846 and named for Lorenzo de Zavala, a Mexican colonist and one of the signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence.[9] The county was organized in 1858, with an error putting an additional “L” in the county. The mistake was not corrected until 1929. Batesville became the county seat. Crystal City won a 1928 election to become the new county seat.[10] Grey (Doc) White and the Vivian family settled Cometa circa 1867. They were joined by the Ramón Sánchez and Galván families in 1870 and by J. Fisher in 1871.[11] Murlo community was settled about the same time.[12] Ranching dominated the county originally, until overgrazing destroyed the grasslands. Zavala then became the first county in Texas to grow flax commercially.[13] Ike T. La Pryor the largest ranch in the county and advertised the land for farming. The community that sprang up was named La Pryor.[14] Developers E. J. Buckingham and Carl Groos purchased all 96,101 acres (388.91 km2) of the Cross S Ranch in 1905, platted the town of Crystal City, and sold the rest as sections divided into 10-acre (40,000 m2) farms.[15]

Winter Garden

Zavala, Dimmitt, Frio and LaSalle counties are considered the Winter Garden Region of Texas.[16] Irrigation and mild winter climate has made the area ideal for year-round vegetable farming. During the winter of 1917–18 spinach was introduced to Zavala.[17] The first annual Spinach Festival was introduced in 1936, halted during World War II, but resumed in 1982.[18] Cartoonist E. C. Segar who created the spinach-eating Popeye received a letter of appreciation from the Winter Garden Chamber of Commerce, thanking him for his support of Spinach in the American diet. Segar’s written response appeared in two newspapers exhorting children everywhere to enjoy Segar’s favorite vegetable. He later approved a 1937 statue of Popeye to be erected in Crystal City, dedicated “To All The Children of the World”.[19] Bermuda onions became a major crop. Spinach, sorghum, and cotton were the three biggest crops. The principal crops grown in Zavala County in 1989 were spinach, cotton, pecans, corn, and onions.[13]

Internment Camp

The Crystal City, Texas Family Internment Camp began as a migrant labor camp in the 1930s. By the time it closed, it had held German and Japanese combatants and their families, Latin Americans and at least one Italian Latin American family, as well as German and Japanese American families. There were 100 acres (0.40 km2) for housing and security measures. An additional 190 acres (0.77 km2) were for farming and personnel residences. The first internees, of German ethnicity, arrived on December 12, 1942, and were expected to work on construction, being paid 10 Cents an hour. A 70-bed hospital was built in 1943, as was a school for children of the internees. Internees ran nursery schools and kindergartens. From its inception through June 30, 1945, the Crystal City camp held 4,751 internees and saw 153 births. The camp closed in 1948.[20]

Mexican Americans

The Mexican Revolution that began in 1910 resulted in thousands of laborers flowing across the border to cultivate vegetable crops. By 1917 and 1918 Pancho Villa was sending banditos across the Rio Grande. Crystal City organized home guards for protection against Villa's associates. By 1930 Crystal City was overwhelmingly composed of Mexican Americans. That year, Zavala County had the highest percentage of laborers (1,430 per 100 farms) and the lowest percentage of tenants (33 per 100 farms) of all counties in South Texas. Owner-operators were primarily Anglo, whereas sharecroppers and farm laborers were Hispanic. By the late 1950s a majority of those graduating from high school in the county were Mexican American. In 1990, 89.4 percent of the county population of 12,162 were Hispanic.[21]

Tejano politics

Juan Cornejo of the Teamsters Union and The Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations organized the Hispanic population among cannery workers and farm laborers of Crystal City in 1962–63 and succeeded in electing an all Latino city council. The feat became known as the Crystal City Revolts.[22][23] The Raza Unida Party was established in 1970 in Crystal City and Zavala County to bring greater self-determination among Tejanos.[24]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 1,302 square miles (3,370 km2), of which 1,297 square miles (3,360 km2) is land and 4.3 square miles (11 km2) (0.3%) is water.[25]

Major highways

Adjacent counties

- Uvalde County (north)

- Frio County (east)

- Dimmit County (south)

- Maverick County (west)

- La Salle County (southeast)

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 26 | — | |

| 1870 | 138 | 430.8% | |

| 1880 | 410 | 197.1% | |

| 1890 | 1,097 | 167.6% | |

| 1900 | 792 | −27.8% | |

| 1910 | 1,889 | 138.5% | |

| 1920 | 3,108 | 64.5% | |

| 1930 | 10,349 | 233.0% | |

| 1940 | 11,603 | 12.1% | |

| 1950 | 11,201 | −3.5% | |

| 1960 | 12,696 | 13.3% | |

| 1970 | 11,370 | −10.4% | |

| 1980 | 11,666 | 2.6% | |

| 1990 | 12,162 | 4.3% | |

| 2000 | 11,600 | −4.6% | |

| 2010 | 11,677 | 0.7% | |

| Est. 2015 | 12,235 | [26] | 4.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[27] 1850–2010[28] 2010–2014[1] | |||

As of the census[29] of 2000, there were 11,600 people, 3,428 households, and 2,807 families residing in the county. The population density was 9 people per square mile (3/km²). There were 4,075 housing units at an average density of 3 per square mile (1/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 65.06% White, 0.49% Black or African American, 0.59% Native American, 0.09% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 31.08% from other races, and 2.66% from two or more races. 91.22% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 3,428 households out of which 43.80% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.10% were married couples living together, 21.80% had a female householder with no husband present, and 18.10% were non-families. 16.60% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.10% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.28 and the average family size was 3.70.

In the county, the population was spread out with 34.10% under the age of 18, 10.20% from 18 to 24, 25.60% from 25 to 44, 18.70% from 45 to 64, and 11.30% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29 years. For every 100 females there were 97.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.80 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $16,844, and the median income for a family was $19,418. Males had a median income of $22,045 versus $14,416 for females. The per capita income for the county was $10,034. About 37.40% of families and 41.80% of the population were below the poverty line, including 48.90% of those under age 18 and 42.40% of those age 65 or over. The county's per-capita income makes it one of the poorest counties in the United States.

Communities

- Batesville

- Cometa

- Chula Vista-River Spur

- Crystal City (county seat)

- La Pryor

- Las Colonias

- Loma Vista

See also

References

- 1 2 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "Texas: Individual County Chronologies". Texas Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. The Newberry Library. 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Tortuga Flat". Texas Beyond History. UT-Austin. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Campbell, Thomas N. "Pacuache Indians". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ "Chaparrosa Ranch". Texas Beyond History. UT-Austin. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Wranker, Ralph. "The South Texas Area". Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Bartlett, Richard C; Williamson, Leroy; Sansom, Andrew; Thornton III, Robert L (1995). "The South Texas Plains". The Wild Horse Desert. University of Texas Press. pp. 123–141. ISBN 978-0-292-70835-8.

- ↑ "Lorenzo de Zavala". Lone Star Junction. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ "Batesville, Texas". Texas Escapes. Texas Escapes - Blueprints For Travel, LLC. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Ochoa, Ruben E. "Cometa, Texas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Ochoa, Ruben E. "Murlo, Texas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- 1 2 Ochoa, Ruben E. "Zavala County". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Ochoa, Ruben E. "La Pryor, Texas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Odintz, Mark. "Crystal City, Texas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Odintz, Mark. "Winter Garden Region". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Mortensen, E. "Spinach Culture". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Usler, Mark (2008). "Crystal City: Spinach Capital of the World". Hometown Declarations - America's Self-Proclaimed World Capitals. DM Enterprises In. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-9786987-1-3.

- ↑ Reavis, Dick J (June 1987). "The Importance of Popeye". Texas Monthly: 98,100.

- ↑ Dickerson, James L (2010). "The Konzentrationslager Blues". Inside America's Concentration Camps: Two Centuries of Internment and Torture. Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 145–160. ISBN 978-1-55652-806-4.

- ↑ Arreola, Daniel David (2002). "Homeland Forged". Tejano South Texas: A Mexican American Cultural Province. University of Texas Press. pp. 43–63. ISBN 978-0-292-70511-1.

- ↑ Acosta, Teresa Paloma. "The Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Acosta, Teresa Paloma. "Crystal City Revolts". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ↑ Ruiz, Vicki (2006). Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia (Volume 1). Indiana University Press. pp. 367–368. ISBN 978-0-253-34681-0.

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ↑ "County Totals Dataset: Population, Population Change and Estimated Components of Population Change: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ↑ "Texas Almanac: Population History of Counties from 1850–2010" (PDF). Texas Almanac. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

External links

- Zavala County government's website

- Zavala County from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Historic Zavala County materials, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- "Zavala County Profile" from the Texas Association of Counties

|

Uvalde County |  | ||

| Maverick County | |

Frio County | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Dimmit County |

Coordinates: 28°52′N 99°46′W / 28.86°N 99.76°W