Zephaniah Kingsley

Zephaniah Kingsley, Jr. (December 4, 1765 – September 14, 1843) was a planter, slave trader, and merchant who built several plantations in the Spanish colony of Florida in what is now Jacksonville. He served on the Florida Territorial Council after Florida was acquired by the United States in 1821.

A plantation that he owned and lived at for 25 years is preserved as Kingsley Plantation, part of the Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve that is run by the United States National Park Service.

Kingsley was a relatively lenient slave owner who gave his slaves the opportunity to earn their freedom. He married a total of four slave women, practicing polygamy. His first wife, Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley, was a 13-year-old slave when Kingsley purchased her. He took her as his common-law wife and later trusted her with running his plantation when he was away on business. He had a total of nine mixed-race children with his wives. He educated his children and worked to settle his estate on them and his wives.

His interracial family and his business interests caused Kingsley to be heavily invested in the Spanish system of slavery and society. Like the French colonies, it provided for certain rights to a class of free people of color and allowed multiracial children to inherit property.

Kingsley became involved in politics when control of the Florida colony passed from Spain to the United States in 1821. He tried to persuade the new territorial government to maintain the special status of the free black population. Unsuccessful, in 1828 he published a treatise that defended a system of slavery that would allow slaves to purchase their freedom and give rights to free blacks and free people of color. Faced with American laws that forbade interracial marriage, Kingsley relocated his large family to Haiti between 1835 and 1837. After his death, his estate in Florida was the subject of dispute between his widow Anna Jai and other members of Kingsley's family.

Early life and education

Kingsley was born in Bristol, England, the second of eight children, to Zephaniah Kingsley, Sr., a Quaker from London, and Isabella Johnstone of Scotland.[1] The elder Kingsley moved his family to the Colony of South Carolina in 1770. His son was educated in London during the 1780s; Zephaniah Kingsley, Sr. purchased a rice plantation near Savannah, Georgia, and several other properties throughout the colonies and Caribbean islands. In total, he owned probably around 200 slaves in all.[2] Like other British loyalists, Kingsley, Sr. was forced to leave South Carolina with his family; he relocated to New Brunswick, Canada in 1782 following the American Revolutionary War, where the Crown provided him some land in compensation for his losses.[3][4]

His son Zephaniah Kingsley, Jr. returned to Charleston, South Carolina in 1793, swore his allegiance to the United States, and began a career as a shipping merchant. His first ventures were in Haiti, during the Haitian Revolution, where coffee was his main interest as an export crop.[5] He lived in Haiti for a brief period while the fledgling nation was working to create a society based on former slaves transitioning as free citizens. Kingsley traveled frequently, prompted by recurring political unrest among the Caribbean islands.[6]

The instability affected his business interests, but development of the Deep South in the United States sharply increased the demand for slaves. Kingsley began to travel to West Africa to procure Africans to be traded as slaves between America, Brazil, and the West Indies.[7] In 1798 he became a Danish citizen in the Danish West Indies;[8] He continued to make his living trading slaves and shipping other goods into the 19th century, although the US prohibited the African slave trade in 1807, effective in 1808. Kingsley became a citizen of Spanish Florida in 1803, and many slaves were smuggled into there and into the US.[5]

Laurel Grove

Spain was offering land to settlers in order to populate Florida, so Kingsley petitioned the governor for land but was turned down. After waiting, he decided to purchase a 2,600-acre (11 km2) farm for $5,300 ($759,313 in 2009). It was named Laurel Grove, and its main entrance was a dock on Doctors Lake, south of where Orange Park is located today. Kingsley arrived with ten slaves and began to cultivate it immediately.[9] Another source stated he received a substantial land grant because he brought 74 slaves to Florida.[3][10] The plantation grew oranges, sea island cotton, corn, potatoes, and peas.

Kingsley's first slaves came from his family's plantation in South Carolina. By 1811, he had acquired a total of 100 slaves at Laurel Grove, obtained from Africa via Cuba.[11] Kingsley trained the slaves at Laurel Grove in agricultural vocations for future sale; he provided slave buyers with skilled artisans, which allowed him to charge 50 percent more than market price per slave.[3][10] At Laurel Grove, slaves were trained not only in farming, but blacksmithing, carpentry, and cotton ginning.[12]

In 1806, Kingsley took a trip to Cuba, where he purchased Anna Madgigine Jai (born as Anta Majigeen Ndiaye), a 13-year-old Wolof girl from what is now Senegal. He married her in an African ceremony in Havana soon after purchasing her.[13] The union was not legally recognized by Spanish Florida or the United States during their lives.[14][15] Kingsley took Anna to Laurel Grove and gradually depended on her to run the plantation in his absence.[16][note 1]

In 1811, he petitioned the colonial Spanish government to free Anna and their three mixed-race children, and the request was granted. The Laurel Grove plantation during one year earned $10,000 ($128,940 in 2009), which was an extraordinary amount for Florida. With his earnings, Kingsley purchased several locations on the opposite side of the St. Johns River, including St. Johns Bluff, San Jose, and Beauclerc in what is now Jacksonville, and Drayton Island farther south near Lake George.[3]

After gaining freedom, Anna Kingsley was awarded five acres in a land grant by the Spanish government, and she purchased slaves to help farm it.[13][17][18]

Zephaniah Kingsley became involved in the shipping industry, including the coastwise trade, related to his large-scale slave trading. While at Laurel Grove, Kingsley was attempting to smuggle in 350 slaves (the international slave trade was abolished in 1807) when the ship was captured by the U.S. Coast Guard. Not knowing what to do with so many indigent people, the Coast Guard turned them over to Kingsley, who was the only person in the area who could care for such a number.[10]

During an insurgency that became known as the Patriot Rebellion, in an attempt to annex Florida to the United States, American forces, American-supplied Creek, and renegades from Georgia, crossed the border into the Spanish colony and began raiding the few settlements in North Florida. They enslaved the black people they captured. In 1813, the Americans captured Kingsley and forced him to sign an endorsement of the rebellion.[note 2]

The insurgents occupied Laurel Grove, using it as a base to raid other plantations and nearby towns. Kingsley left the area. After assuring her safety with the Spanish forces, Anna burned the plantation down so the rebels could not use it; she took her children and a dozen slaves aboard a Spanish gunboat to escape the conflict.[19] For her loyalty, Anna received a reward of 350 acres (1.4 km2) from the Spanish colonial government.[13]

Fort George Island

Kingsley and Anna moved to a plantation on Fort George Island at the mouth of the St. Johns River in 1814; they remained there for 25 years. Anna and Kingsley's fourth and last child was born on Fort George Island in 1824.

Kingsley took three younger slave women as common-law wives and fathered mixed-race children with at least two of them, totaling nine children in all.[20] All three women were slaves whom he eventually freed: they were named Flora Kingsley, Sarah Kingsley, who brought her son Micanopy; and Munsilna McGundo, who brought her daughter Fatima. The Kingsley family was, according to historian Daniel Stowell, "complex at best".[14] In his will, the only woman Kingsley named as his wife was Anna. Primary documentation by Kingsley is scarce, but historians consider Flora, Sarah, and McGundo as "lesser wives",[3] or "co-wives" with Anna.[21] Stowell suggests "concubines" is a more accurate description of their status.[14] Kingsley lavished all his children with affection, attention, and luxury. They were educated with the best European teaching he could afford.[22] When he entertained visitors at his Fort George plantation, Anna sat "at the head of the table"; they were "surrounded by healthy and handsome children" in a parlor decorated with portraits of African women.[23]

The plantation featured a main house and a two-story structure with a kitchen on the ground floor and living quarters on the second called the "Ma'am Anna House". Anna lived with her children in the custom among the Wolof people.

The plantation produced oranges, sea island cotton, indigo, okra, and other vegetables. Approximately 60 slaves were managed under the task system: each slave had a quota of work to do per day. When they were finished, they were allowed to do what they wished.[13][24] Some slaves had personal gardens which they were allowed to cultivate, and from which they sold vegetables. Thirty-two cabins were constructed for and by the slaves, made from tabby, which made them durable, insulated, and inexpensive although labor-intensive. The cabins were located about a quarter of a mile (400 m) from the main house. Slaves were allowed to padlock their cabins and build porches that faced away from the main house. Both of these features were unusual for slave quarters in antebellum America.[25]

Restrictions under a new government

Following the transfer of Florida from Spain to the United States in 1821, President James Monroe appointed Kingsley to serve on Florida's Territorial Council, which began to establish an American government. The Council focused primarily on allowing immigrants to Florida access to the 40,000,000 acres (160,000 km2) ceded by Spain, and removing the Seminole to Indian Territory.[26] Americans settled in the central portion of Florida and built productive plantations worked by slaves. They were used to the binary racial caste system that had developed throughout the Southeastern U.S. This system contrasted with the standing practice in which Kingsley was invested, which, based on Spanish law as implemented in Florida, supported three social tiers of whites, free people of color, and slaves. The Spanish government recognized interracial marriages and allowed mixed-race children to inherit property.

Kingsley's first task with the Territorial Council was an attempt to persuade them to determine a favorable place for the free people of color in a U.S.-controlled Florida. He addressed the council stating, "I consider that our personal safety as well as the permanent condition of our Slave property is intimately connected with and depends much on our good policy in making it the interest of our free colored population to be attached to good order and have a friendly feeling towards the white population."[27]

When it became apparent to Kingsley that the council could not make a decision on the rights of free blacks and mixed-race people, he resigned his position.[28] Through the 1820s the council began to enact strict laws separating the races, and Kingsley became worried about his future and the rights of his family. To address these issues, in 1828 he wrote a pamphlet titled A Treatise on the Patriarchal or Co-operative System of Society as it Exists in Some Governments, and Colonies in America, and the United States Under the Name of Slavery With its Necessary Advantages crediting himself as "An Inhabitant of Florida", defending the system to which he had become accustomed. In it, he wrote,

"Slavery is a necessary state of control from which no condition of society can be perfectly free. The term is applicable to and fits all grades and conditions in almost every point of view, whether moral, physical, or political."[3]

Kingsley asserted that when slavery is associated with cruelty it is an abomination; when it is joined with benevolence and justice, it "easily amalgamates with the ordinary conditions of life".[3][29]

He wrote that Africans were better suited than Europeans for labor in hot climates (a shared stereotype), and that their happiness was maximized when they were rigidly controlled; their contentment was greater than whites of a similar class. He asserted that people of mixed race were healthier and more beautiful than either Africans or Europeans, and considered his mixed race children a barrier to an impending race war.[3][30]

The treatise was published four times, the last printing in 1834. Reception was mixed. While some Southerners used it to defend the institution of slavery, others saw Kingsley's support of a free class of blacks as a prelude to the abolition of it.[31] abolitionists considered Kingsley's arguments for slavery weak and wrote that logically, the planter should conclude that slavery must be eradicated. Lydia Child, a New York-based abolitionist, included him in 1836 on a list of people perpetuating the "evils of slavery".[32] Although Kingsley was wealthy, learned, and powerful, the treatise was a factor in the decline of his reputation in Florida. He became embroiled in a political scandal with Florida's first governor, William DuVal. The governor was quoted in newspapers making scathingly critical remarks about Kingsley's motives and his mixed-race family after the planter petitioned to have DuVal removed from his office for corruption.[33]

Haiti

After trying to persuade the new government of Florida to provide for rights for free people of color, including the right of mixed-race children to inherit property from their fathers, Kingsley began to think the independent republic of Haiti was more conducive to what he wanted to achieve. Haiti's government was actively recruiting free blacks from across the Americas to settle the island, offering them land and citizenship.[34] Kingsley highlighted its successes as a nation of free blacks in his treatise, writing

"...under a just and prudent system of management, negroes are safe, permanent, productive and growing property, and easily governed; that they are not naturally desirous of changes, but are sober, discreet, honest and obliging, are less troublesome, and possess a much better moral character than the ordinary class of corrupted whites of a similar condition."[35]

Kingsley's praise of Haiti's new system—which outlawed slavery—combined with his defense of slavery, is notable to author Mark Fleszar, who comments that the paradox in Kingsley's thinking indicated a "disordered worldview".[36] He was determined to create the society he had written about and defended.

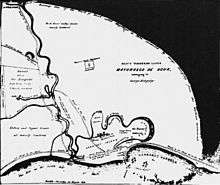

Kingsley's son George and six of his slaves arrived in Haiti to scout for land, finding a suitable location on the northeastern shore of the island, in what is today the Puerto Plata Province of the Dominican Republic. By 1835 it became evident Kingsley realized that his marriage to Anna would not be recognized in the United States, and, in the event of his death, holdings in the name of Anna, Flora, Sarah, McGundo, and their mixed-race children might be confiscated. Over the next two years, most of Kingsley's extensive family relocated. Two of his daughters stayed in Florida, as they had married local white planters. The others went with him to a plantation named Mayorasgo de Koka, which was worked by more than 50 slaves transplanted from the Fort George Island plantation. In Haiti, the workers were contracted to work as indentured servants, who would earn their full freedom after nine years of labor.[37]

Death and property disputes

After visiting his family in Haiti in 1843, Kingsley boarded a ship going to New York City to conduct business there. His death of pulmonary disease at 78 years old was recorded in New York City, where Kingsley was buried in a Quaker cemetery. He left much of his land to his wives and children, a bequest which was immediately contested on racial grounds by his white relatives. Kingsley's niece, Anna McNeill (who married George Whistler; their son James Whistler became a noted artist) was among the family members who tried to have all of Kingsley's family of African descent excluded from his will.[3] Kingsley's will stipulated that no remaining slaves should be separated from their families, and that they should be given the opportunity to purchase their freedom at half their market price. Anna Madgigine Jai, who kept her African name through the marriage, returned to Florida in 1846 to oppose Kingsley's white relatives in court in Duval County. Arguing her case within the dictates of the Adams–Onís Treaty, she was successful; an extraordinary achievement in light of the state and local policy that was hostile toward freed slaves or blacks of any status.[38]

After a brief period in Florida during the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865), Anna fled to New York as she supported the Union. After the war, she returned to Florida. Anna Madgigine Jai died in April or May 1870 on a farm in the Arlington neighborhood of Jacksonville. She was buried there in an unmarked grave.[13]

Post Civil War

The Fort George plantation was sold soon after Kingsley's death. After the Civil War, the Freedmen's Bureau controlled the island until 1869, when it was purchased by another planter. The island changed hands under private ownership until 1955, when it was acquired by the Florida Park Service. Kingsley's house, "the oldest standing plantation house in Florida";[39] Ma'am Anna House, and the barn survived the years relatively intact. Most of the slave quarters did as well. The National Park Service established the Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve in 1988 and acquired 60 acres (0.24 km2) of land surrounding the Kingsley Plantation buildings in 1991.[40]

Notes

- ↑ Mark Fleszar writes that interpretations of how much Anna managed Laurel Grove "deserves caution", as Kingsley's letters indicate white overseers were responsible for the day-to-day issues of the plantation when he was away on business. Kingsley told abolitionist Lydia Child in an interview that Anna "was very capable, and could carry on all the affairs of the plantation in my absence, as well as I could myself." He either deliberately misrepresented other details in his life or Child's reporting was inaccurate, calling into question other statements Kingsley was reported to have made. (Fleszar, p. 72.)

- ↑ John McIntosh, owner of the Fort George Plantation before Kingsley, accused him in 1826 of financially supporting the war. The accusation may have been politically motivated, as Kingsley suddenly resigned his position from the Territorial Council, and McIntosh was angry about the public treatment he had received since the war for his role in it. (Fleszar, p. 135.)

Citations

- ↑ Fleszar, p. 9.

- ↑ Fleszar, pp. 17–18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 May, Philip S. (January 1945). "Zephaniah Kingsley, Nonconformist", The Florida Historical Quarterly 23 (3), pp. 145–159.

- ↑ Fleszar, p. 23.

- 1 2 Stowell, p. 2.

- ↑ Fleszar, pp. 35–39.

- ↑ Fleszar, pp. 40–44.

- ↑ Schafer, p. 21.

- ↑ Fleszar, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 Williams, Edwin (October 1949). "Negro Slavery in Florida". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 28 (2): 94–110. JSTOR 30138779.

- ↑ Stowell, p. 3.

- ↑ McTammany, Mary Jo (May 26, 1999). "Laurel Grove Was 'Real' Orange Park", Florida Times-Union (Jacksonville, FL), p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mallard, Kiley (Winter 2007). "The Kingsley Plantation: Slavery in Spanish Florida", Florida History and the Arts, pp. 1–7.

- 1 2 3 Stowell, p. 4.

- ↑ Fleszar, p. 68.

- ↑ Schafer, p. 34.

- ↑ "Anna Kingsley: A Free Woman", Timucuan Ecological and Historical Park, National Park Service, accessed May 14, 2010.

- ↑ Fleszar, p. 76.

- ↑ Schafer, pp. 37–42.

- ↑ Fleszar, p. 139.

- ↑ Schafer, p. 56.

- ↑ Fleszar, p. 133.

- ↑ Stowell, p. 108.

- ↑ Labor, Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, National Park Service (July 6, 2006). Retrieved on July 10, 2009.

- ↑ Davidson, James M.; Roberts, Erika, and Rooney, Clete "Preliminary Results of the 2006 University of Florida Archaeological Field School Excavations at Kingsley Plantation, Fort George Island, Florida", African Diaspora Archeology Network. Retrieved on July 10, 2009.

- ↑ Gannon, p. 215.

- ↑ Stowell, p. 30.

- ↑ Fleszar, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Fleszar, p. 148.

- ↑ Brown, Cantor (January 1995). "Race Relations in Territorial Florida", The Florida Historical Quarterly, pp. 287–307.

- ↑ Fleszar, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Fleszar, pp. 154–156.

- ↑ Fleszar, pp. 150–152.

- ↑ Stowell, p. 19.

- ↑ Kingsley, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Fleszar, p. 157.

- ↑ Stowell, p. 20.

- ↑ Schafer, p. 72.

- ↑ "Archaeology Field School", Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, National Park Service, accessed May 15, 2010.

- ↑ Stowell and Tilford, pp. 17–21.

References

- Bennett, Charles(1989). Twelve on the River St. Johns, University of North Florida Press. ISBN 0-8130-0913-8.

- Fleszar, Mark (2009). The Atlantic Mind: Zephaniah Kingsley, Slavery, and the Politics of Race in the Atlantic World, Georgia State University. .

- An Inhabitant of Florida (Zephaniah Kingsley, Jr). (1829). A Treatise on the Patriarchal or Co-operative System of Society as it Exists in Some Governments, and Colonies in American, and the United States Under the Name of Slavery With its Necessary Advantages, reprinted 2005 by Eastern National.

- Gannon, Michael (ed.) (1996). A New History of Florida, University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1415-8

- Schafer, Daniel L. (2003). Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley: African Princess, Florida Slave, Plantation Slaveowner, University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2616-4

- Stowell, Daniel (ed.) (2000). Balancing Evils Judiciously: The Proslavery Writings of Zephaniah Kingsley, University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2400-5

- Stowell, Daniel and Tilford, Kathy (1998). Kingsley Plantation: A History of Fort George Island Plantation, Eastern National. ISBN 1-888213-23-X

- Wu, Kathleen (2010). "Manumission of Anna: Another Interpretation" in El Escribano: The St. Augustine Journal of History, 46. ISSN 0014-0376.

External links

- Kingsley Plantation Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve

- Zephaniah Kingsley Collection and the University of Florida