Alexander Selkirk

| Alexander Selkirk | |

|---|---|

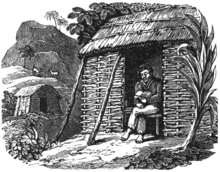

Clad in goatskins, Selkirk awaits rescue in a sculpture by Thomas Stuart Burnett (1885) | |

| Born |

1676 Lower Largo, Fife, Scotland |

| Died |

13 December 1721 (aged 45) Cape Coast, Ghana |

| Nationality | Scottish and British (after 1707) |

| Occupation | Sailor |

| Known for | Inspiring Robinson Crusoe |

Alexander Selkirk (1676 – 13 December 1721) was a Scottish privateer and Royal Navy officer who spent more than four years as a castaway (1704–1709) after being marooned by his captain on an uninhabited island in the South Pacific Ocean. He survived that ordeal, but succumbed to tropical illness a dozen years later while serving aboard HMS Weymouth off West Africa.

Selkirk was an unruly youth, and joined buccaneering voyages to the South Pacific during the War of the Spanish Succession. One such expedition was on Cinque Ports, commanded by William Dampier. The ship called in for provisions at the Juan Fernández Islands, and Selkirk judged correctly that the craft was unseaworthy and asked to be left there.

When he was eventually rescued by follow-on English privateer Woodes Rogers, Selkirk had become adept at hunting and making use of the resources he found on the island. His story of survival was widely publicised after their return to England, becoming a source of inspiration for writer Daniel Defoe's fictional character Robinson Crusoe.

Early life and privateering

Alexander Selkirk was the son of a shoemaker and tanner in Lower Largo, Fife, Scotland, born in 1676.[1] In his youth, he displayed a quarrelsome and unruly disposition. He was summoned before the Kirk Session in August 1693[2] for his "indecent conduct in church", but he "did not appear, being gone to sea." He was back at Largo in 1701, when he again came to the attention of church authorities for beating up his brothers.[3]

Early on, he was engaged in buccaneering. In 1703, he joined an expedition of English privateer and explorer William Dampier to the South Pacific Ocean,[4] setting sail from Kinsale in Ireland on 11 September.[5] They carried letters of marque from the Lord High Admiral authorising their armed merchant ships to attack foreign enemies as the War of the Spanish Succession was then going on between England and Spain.[6] Dampier was captain of St George, and Selkirk served on Cinque Ports, St George's companion ship, as sailing master under Captain Thomas Stradling.[7] By this time, Selkirk must have had considerable experience at sea.[3]

In February 1704, following a stormy passage around Cape Horn,[8] the privateers fought a long battle with a well-armed French vessel, St Joseph, only to have it escape to warn its Spanish allies of the buccaneers' arrival in the Pacific.[9] A raid on the Panamanian gold mining town of Santa María failed when their landing party was ambushed.[10] The easy capture of Asunción, a heavily-laden merchantman, revived the men's hopes of plunder, and Selkirk was put in charge of the prize ship. Dampier took off some much-needed provisions of wine, brandy, sugar and flour; then abruptly set the ship free, arguing that the gain was not worth the effort. In May 1704, Stradling decided to abandon Dampier and strike out on his own.[11]

Castaway

In September 1704, after parting ways with Dampier,[12] Captain Stradling brought Cinque Ports to an island known to the Spanish as Más a Tierra located in the uninhabited Juan Fernández archipelago 670 km (420 mi) off the coast of Chile for a mid-expedition restocking of fresh water and supplies.[13]

Selkirk had grave concerns about the seaworthiness of their vessel and probably wanted to make the needed repairs before going any farther. He declared that he would rather stay on Juan Fernández than continue in a dangerously leaky ship.[14] Willing to be rid of a troublemaker, Stradling took him up on the offer and landed Selkirk on the island with a musket, gunpowder, a hatchet, a knife, a kettle, a Bible and some clothing.[15] Selkirk regretted his rashness, but Stradling refused to let him back on board.[14]

Cinque Ports did indeed later founder off the coast of what is now Colombia. Stradling and some of his crew survived the loss of their ship but were forced to surrender to the Spanish. The survivors were taken to Peru where they endured a harsh imprisonment.[16]

Life on the island

At first, Selkirk remained along the shoreline of Juan Fernández. During this time, he ate spiny lobsters and scanned the ocean daily for rescue, suffering all the while from loneliness, misery and remorse. Hordes of raucous sea lions, gathered on the beach for the mating season, eventually drove him to the island's interior.[17] Once inland, his way of life took a turn for the better. More foods were available there: feral goats—introduced by earlier sailors—provided him with meat and milk, while wild turnips, cabbage leaves and dried pepper berries offered him variety and spice. Rats would attack him at night, but he was able to sleep soundly and in safety by domesticating and living near feral cats.[18]

Selkirk proved resourceful in using materials that he found on the island: he forged a new knife out of barrel hoops left on the beach,[19] he built two huts out of pepper trees, one of which he used for cooking and the other for sleeping, and he employed his musket to hunt goats and his knife to clean their carcasses. As his gunpowder dwindled, he had to chase prey on foot. During one such chase, he was badly injured when he tumbled from a cliff, lying helpless and unable to move for about a day. His prey had cushioned his fall, probably sparing him a broken back.[20]

Childhood lessons learned from his father, a tanner, now served him well. For example, when his clothes wore out, he made new ones from hair-covered goatskins using a nail for sewing. As his shoes became unusable, he had no need to replace them, since his toughened, calloused feet made protection unnecessary.[19] He sang psalms and read from the Bible, finding it a comfort in his situation and a prop for his English.[15]

During his sojourn on the island, two vessels came to anchor. Unfortunately for Selkirk, both were Spanish. As a Scotsman and a privateer, he risked a grim fate if captured and, therefore, tried to hide himself. On one occasion, he was spotted and chased by a group of sailors from one of the ships. His pursuers urinated beneath the tree in which he was hiding but failed to discover him. Frustrated, his would-be captors gave up and sailed away.[14]

Rescue

Selkirk's long-awaited deliverance came on 2 February 1709 by way of Duke,[21] a privateering ship piloted by William Dampier, and its sailing companion Duchess.[22] Thomas Dover led the landing party that met Selkirk.[23] After four years and four months without human company, Selkirk was almost incoherent with joy.[24] The Duke's captain and leader of the expedition was Woodes Rogers, who mischievously referred to him as the governor of the island. The agile castaway caught two or three goats a day and helped restore the health of Rogers' men, who were suffering from scurvy.[25]

Captain Rogers was impressed by Selkirk's physical vigour, and also by the peace of mind that he had attained while living on the island, observing: "One may see that solitude and retirement from the world is not such an insufferable state of life as most men imagine, especially when people are fairly called or thrown into it unavoidably, as this man was".[26] He made Selkirk the Duke's second mate, later giving him command of one of their prize ships, Increase,[27] before it was ransomed by the Spanish.[28]

Selkirk returned to privateering with a vengeance. At Guayaquil, in present-day Ecuador, he led a boat crew up the Guayas River, where a number of wealthy Spanish ladies had fled, and relieved them of the gold and jewels they had hidden inside their clothing.[29] His part in the hunt for treasure galleons along the coast of Mexico resulted in the capture of the Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación y Desengaño,[30] renamed Bachelor, on which he served as sailing master under Captain Dover to the Dutch East Indies.[31] Selkirk completed the around-the-world voyage by the Cape of Good Hope as the sailing master of Duke,[32] arriving at the Downs off the English coast on 1 October 1711.[33] He had been away for eight years.[5]

Later life and influence

Selkirk's experience as a castaway aroused a great deal of attention in England. Rogers included an account of Selkirk's ordeal in a book chronicling their privateering expedition entitled A Cruising Voyage Round the World (1712). The following year, prominent essayist Richard Steele wrote an article about him for The Englishman newspaper. Selkirk appeared set to enjoy a life of ease and celebrity, claiming his share of Duke's plundered wealth—about £800[34] (equivalent to £107,400 today).[35] However, legal disputes made the amount of any payment uncertain.[36]

After a few months in London, he began to seem more like his former self again.[34] In September 1713, he was charged with assaulting a shipwright in Bristol and may have been kept in confinement for two years.[37] He returned to Lower Largo, where he met Sophia Bruce, a young dairymaid. They eloped to London early in 1717 but apparently did not marry. He was soon off to sea again, having enlisted in the Royal Navy.[38] While on a visit to Plymouth in 1720, he married a widowed innkeeper named Frances Candis.[39] He was serving as master's mate on board HMS Weymouth, engaged in an anti-piracy patrol off the west coast of Africa, when he died on 13 December 1721, succumbing to the yellow fever that plagued the voyage. He was buried at sea.[40]

When Daniel Defoe published The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1719), few readers could have missed the resemblance to Selkirk. An illustration on the first page of the novel shows "a rather melancholy-looking man standing on the shore of an island, gazing inland", in the words of modern explorer Tim Severin. He is dressed in the familiar hirsute goatskins, his feet and shins bare.[41] Yet Crusoe's island is located not in the mid-latitudes of the South Pacific but 4,300 km (2,700 mi) away in the Caribbean, where the furry attire would hardly be comfortable in the tropical heat. This incongruity supports the popular belief that Selkirk was a model for the fictional character,[42] although literary scholars now accept that his was "just one of many survival narratives that Defoe knew about."[43]

In other literary works

| Wikisource has the original text of William Cowper's: |

- William Cowper's "The Solitude Of Alexander Selkirk" is about Selkirk's feelings as the castaway lived all alone on the island. This poem gave rise to the common phrase "monarch of all I survey" via the verse:

I am monarch of all I survey,

My right there is none to dispute;

From the centre all round to the sea,

I am lord of the fowl and the brute.[1]

- ^ Ravitch & Ravitch (2006), p. 134.

- Charles Dickens used Selkirk as a simile in Chapter Two of The Pickwick Papers (1836): "Colonel Builder and Sir Thomas Clubber exchanged snuff-boxes, and looked very much like a pair of Alexander Selkirks—'Monarchs of all they surveyed.'"[44] This is also a reference to William Cowper's poem.[45]

- Poet Patrick Kavanagh likens his loneliness on the road to that of Selkirk, in his poem "Inniskeen Road: July Evening":

Oh, Alexander Selkirk knew the plight

Of being king and government and nation.

A road, a mile of kingdom, I am king

Of banks and stones and every blooming thing.[1]

- ^ Regan (2004), pp. 402–403.

- In "Etiquette", one of W. S. Gilbert's Bab Ballads, Selkirk is used as a model for the English castaways:

These passengers, by reason of their clinging to a mast,

Upon a desert island were eventually cast.

They hunted for their meals, as Alexander Selkirk used,

But they couldn’t chat together—they had not been introduced.[1]

- ^ Gilbert (1970), p. 274.

- Joshua Slocum mentions Selkirk in the book Sailing Alone Around the World (1900). During his visit to the Juan Fernández Islands, Slocum runs across a marker commemorating Selkirk’s stay.[46]

- In Allan Cole and Chris Bunch's Sten science fiction series, Book Two, The Wolf Worlds, the Scottish character Alex bemoans their predicament after crash landing: "'A slackit way f'r a mon,' Alex mourned to himself. 'Ah didnae ken Ah'd ever be Alex Selkirk.'"[47]

In film

Selkirk, the Real Robinson Crusoe is a stop motion film by Walter Tournier based on Selkirk's life. It premièred simultaneously in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay on 2 February 2012,[48] distributed by The Walt Disney Company. It was the first full-length animated feature to be produced in Uruguay.[49]

Commemoration

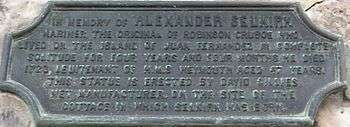

"In memory of Alexander Selkirk, mariner, the original of Robinson Crusoe who lived on the island of Juan Fernández in complete solitude for four years and four months. He died 1723 [sic], lieutenant of HMS Weymouth, aged 47 years [sic]. This statue is erected by David Gillies, net manufacturer, on the site of the cottage in which Selkirk was born."

Selkirk has been memorialised in his Scottish birthplace. Lord Aberdeen delivered a speech on 11 December 1885, after which his wife Lady Aberdeen unveiled a bronze statue and plaque in memory of Selkirk outside a house on the site of his original home on the Main Street of Lower Largo, Fife, Scotland. David Gillies of Cardy House, Lower Largo, a descendant of the Selkirks, donated the statue created by Thomas Stuart Burnett ARSA.[50]

The Scotsman is also remembered in his former island home. In 1869, the crew of HMS Topaze placed a bronze tablet at a spot called Selkirk's Lookout on a hill of Más a Tierra, Juan Fernández Islands, to mark his stay.[51] On 1 January 1966, Chilean president Eduardo Frei Montalva renamed Más a Tierra Robinson Crusoe Island after Defoe's fictional character in order to attract tourists. The largest of the Juan Fernández Islands, known as Más Afuera, became Alejandro Selkirk Island, although Selkirk probably never saw that island since it is located 180 kilometres (110 miles; 100 nautical miles) to the west.[52]

Archaeological findings

An archaeological expedition to the Juan Fernández Islands in February 2005 found part of a nautical instrument that could have belonged to Selkirk. It was "a fragment of copper alloy identified as being from a pair of navigational dividers"[53] dating from the early 18th (or late 17th) century. Selkirk is the only person known to have been on the island at that time who is likely to have had dividers and was even said by Rogers to have had such instruments in his possession.[54] The artefact was discovered while excavating a site not far from Selkirk's Lookout where the famous castaway is believed to have lived.[55]

Notes

- ↑ Howell (1829), pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Takahashi et al. (2007), n. 11, "Date of 1693, verified from the original Kirk Session Records (CH2/960/2, pp. 29, 30), is erroneously given in other printed sources as 1695."

- 1 2 Howell (1829), pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Funnell (1707), pp. 1–2.

- 1 2 Funnell (1707), p. 3.

- ↑ "Letters of Marque and Reprisal for the St George, Declaration of William Dampier". The National Archives. 13 October 1702. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ Howell (1829), pp. 33, 37–38.

- ↑ Funnell (1707), pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Funnell (1707), p. 26.

- ↑ Funnell (1707), pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Funnell (1707), pp. 45–47.

- ↑ Funnell (1707), pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Lee (1987), pp. 394–395.

- 1 2 3 Rogers (1712), p. 125.

- 1 2 Rogers (1712), p. 126.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), pp. 145, 333.

- ↑ Steele (1713), p. 169–171.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), pp. 127–128.

- 1 2 Rogers (1712), p. 128.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), p. 6.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), p. 124.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), p. 129.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), pp. 131–132.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), p. 130.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), p. 147.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), p. 220.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), pp. 178–179.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), p. 294.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), p. 312.

- ↑ Cooke (1712), p. 61.

- ↑ Rogers (1712), p. 427.

- 1 2 Steele (1713), p. 173.

- ↑ Clark, Gregory (2016). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ Souhami (2001), pp. 180–181.

- ↑ Lee (1987), p. 399; cf. Souhami (2001), p. 186, "He did not show up for the hearing. He moved to the obscurity of London for some months, then went home to Largo."

- ↑ Souhami (2001), pp. 190–192.

- ↑ Souhami (2001), pp. 201–202.

- ↑ Souhami (2001), pp. 203–205.

- ↑ Severin (2002), p. 11.

- ↑ Severin (2002), p. 17.

- ↑ Little, Becky (28 September 2016). "Debunking the Myth of the 'Real' Robinson Crusoe". National Geographic. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ↑ Dickens (1836), p. 15.

- ↑ Ravitch & Ravitch (2006), p. 134.

- ↑ Slocum (1900), p. 141.

- ↑ Bunch & Cole (1984), p. 21.

- ↑ "Selkirk, el verdadero Robinson Crusoe". Cine Nacional. 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ "Selkirk llega al DVD con algunas novedades". El País. 8 April 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ "Notable Dates in History". Scots Independent. 2006. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ Severin (2002), p. 59.

- ↑ Severin (2002), pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Takahashi et al. (2007), p. 270.

- ↑ Takahashi et al. (2007), pp. 294–295.

- ↑ Takahashi et al. (2007), pp. 274–275.

References

- Bunch, Chris; Cole, Allan (1984). Sten 2: The Wolf Worlds. London: Orbit Books. ISBN 978-143-44-3107-3.

- Cooke, Edward (1712). A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, Performed in the Years 1708, 1709, 1710 and 1711. 2. London: B. Lintot & R. Gossling.

- Dickens, Charles (1836). The Pickwick Papers. London: Chapman & Hall.

- Funnell, William (1707). A Voyage Round the World, Containing an Account of Captain Dampier's Expedition into the South Seas in the Ship St George in the Years 1703 and 1704. London: W. Botham.

- Gilbert, W. S. (1970). James Ellis, ed. The Bab Ballads. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-067-405801-9.

- Howell, John (1829). The Life and Adventures of Alexander Selkirk. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd.

- Lee, C. D. (1987). "Alexander Selkirk and the Last Voyage of the Cinque Ports Galley". Mariner's Mirror. 73 (4): 385–399. doi:10.1080/00253359.1987.10656168.

- Ravitch, Michael; Ravitch, Diane (2006). The English Reader: What Every Literate Person Needs to Know. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-019-50-7729-2.

- Regan, Stephen (2004). Irish Writing: An Anthology of Irish Literature in English 1789–1939. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-019-95-4982-5.

- Rogers, Woodes (1712). A Cruising Voyage Round the World: First to the South-Sea, Thence to the East-Indies, and Homewards by the Cape of Good Hope. London: A. Bell.

- Severin, Tim (2002). In Search of Robinson Crusoe. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-046-50-7698-7.

- Slocum, Joshua (1900). Sailing Alone Around the World. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-048-620326-3.

- Souhami, Diana (2001). Selkirk's Island: The True and Strange Adventures of the Real Robinson Crusoe. New York: Harcourt Books. ISBN 978-015-60-2717-5.

- Steele, Richard (3 December 1713). "Alexander Selkirk, an Account of His Living Alone Above Four Years in a Desolate Island". The Englishman. 1 (26): 168–173.

- Takahashi, Daisuke; Caldwell, David H.; Cáceres, Iván; Calderón, Mauricio; Morrison-Low, A. D.; Saavedra, Miguel A. & Tate, Jim (2007). "Excavation at Aguas Buenas, Robinson Crusoe Island, Chile, of a Gunpowder Magazine and the Supposed Campsite of Alexander Selkirk, Together with an Account of Early Navigational Dividers". Post-Medieval Archaeology. 41 (2): 270–304. doi:10.1179/174581307X236157.

Further reading

- Kraske, Robert (2005). Marooned: The Strange But True Adventures of Alexander Selkirk. New York: Clarion Books. ISBN 978-061-85-6843-7.

- Takahashi, Daisuke (2002). In Search of Robinson Crusoe. New York: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 978-081-54-1200-7.

- Wilson, Rick (2009). The Man Who Was Robinson Crusoe: A Personal View of Alexander Selkirk. Glasgow: Neil Wilson Publishing. ISBN 978-19-064-7602-1.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1885–1900 Dictionary of National Biography's article about Alexander Selkirk. |

- "Trapped on a Pacific Island: Scientists Research the Real Robinson Crusoe" by Marco Evers (6 February 2009) in Spiegel Online

- "Island Gives Up Secret of Real Robinson Crusoe" in The Scotsman (22 September 2005)

- "The Real Robinson Crusoe" by Bruce Selcraig (July 2005) in Smithsonian

- An account of a trip to Selkirk's Island by James S. Bruce and Mayme S. Bruce (Spring 1993) in The Explorers Journal

- "On a Piece of Stone: Alexander Selkirk on Greater Land" by Edward E. Leslie (1988) in Desperate Journeys, Abandoned Souls: True Stories of Castaways and Other Survivors (pp. 61–85)

- Satellite imagery of the Juan Fernández Islands from Google Maps

-

The Life and Adventures of Alexander Selkirk public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Life and Adventures of Alexander Selkirk public domain audiobook at LibriVox