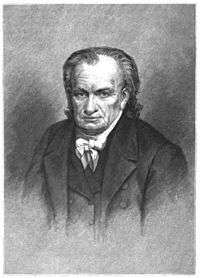

Amos Eaton

| Amos Eaton | |

|---|---|

|

Amos Eaton (1776-1842) | |

| Born |

7 May 1776 Chatham, New York |

| Died |

10 May 1842 (aged 66) Troy, New York |

| Nationality | United States |

| Fields | |

| Institutions |

Williams College Castleton Medical College Rensselaer School |

| Alma mater | Williams College |

| Known for | |

| Influenced |

James Curtis Booth Ezra S. Carr George Hammell Cook James Dwight Dana James Eights Ebenezer Emmons Asa Fitch Asa Gray James Hall Joseph Henry Eben Norton Horsford Douglass Houghton Mary Mason Lyon Almira Hart Lincoln Phelps John Leonard Riddell Abram Sager John Torrey Emma Willard |

| Spouse |

Polly Thomas (m. 1799; d. 1803)[1]:p. 195 Sally Cady (m. 1803; d. 1816)[1]:p. 196 Anna Bradley (m. 1816; d. 1826)[1]:p. 198 Alice Johnson (m. 1827; d. 1831)[1]:p. 226 |

| Children | Twelve[1] |

Amos Eaton (17 May 1776 – 10 May 1842) was an American botanist, geologist, and educator who is considered the founder of the modern scientific prospectus in education, which was a radical departure from the American liberal arts tradition of classics, religious classes, lecture, and recitation.[2][3] Eaton co-founded the Rensselaer School in 1824 with Stephen van Rensselaer III "in the application of science to the common purposes of life".[3][4] His books in the eighteenth century were among the first published for which a systematic treatment of the United States was attempted, and in a language that all could read.[5] His teaching laboratory for botany in the 1820s was the first of its kind in the country.[6][7][8][9] Eaton's popular lectures and writings inspired numerous thinkers, in particular women, whom he encouraged to attend his public talks on experimental philosophy.[10] Emma Willard would found the Troy Female Seminary (Emma Willard School), and Mary Mason Lyon, the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (Mount Holyoke College). Eaton held the rank of senior professor at Rensselaer until his death in 1842.[10][11]

Life

Amos Eaton was born at Chatham, Columbia County, New York on 17 May 1776. His father, Captain Abel Eaton was a farmer of comfortable means. He belonged to a family that traced its lineage to John Eaton, who arrived from Dover, England in 1635, settling two years later in Dedham, Massachusetts Bay Colony. Amos Eaton showed early preference for nature, by the age of sixteen constructing his own compass and chain to survey land as a chain bearer.

Eaton was sent to Williamstown with the Rev. Dr. David Potter, of Spencertown, to study at Williams College. After graduating in 1799 with high marks in natural philosophy, he married the daughter of Malachi and Mary (née McCall) Thomas in October the same year, who died in 1802, leaving him a son. He arranged to study in the legal profession, studying law with the Hon. Elisha Williams, of Spencertown, and the Hon. Josiah Ogden, of New York, receiving admittance to the bar of the Supreme Court of New York. An association that he formed in New York with Dr. David Hosack and Dr. Samuel L. Mitchell, marked another determining point in his career; for, under their instruction, Eaton, became committed to the natural sciences, and in particular botany. Eaton practiced as a lawyer and as a land agent in Catskill, New York until 1810, when he was jailed on charges of forgery, spending nearly five years in prison. On his release in 1815, Eaton removed to New Haven at Yale College to take up the study of botany, chemistry and mineralogy under the tuition of Benjamin Silliman and Eli Ives. He then returned to Williams College to offer a course of lectures and volunteer classes of the students on botany, mineralogy zoology, and geology and published a botanical dictionary. In 1817, he published his Manual of Botany for the Northern States, the first comprehensive flora of the area; it ultimately went through eight editions. From Williams College the lectures were extended, in the shape of courses, with practical instructions to classes, to the larger towns of New England and New York.

He returned to New York State in 1818 to Albany on DeWitt Clinton's preparations for him to deliver a series of lectures to the New York State Legislature on the state's geology in connection with the building of the Erie Canal and agriculture. Among the legislators who heard these lectures was Stephen Van Rensselaer III, patroon of Rensselaerswyck, who, in 1820, hired him to produce A geological Survey of the County of Albany, which was followed by geological surveys of much of the area through which the canal was built. Ultimately, Eaton would complete a survey of a section fifty miles wide from Buffalo to Boston.

Eaton delivered talks at the Lenox Academy and the Medical College at Castleton, Vermont, where he was appointed professor of natural history in 1820. He gave lectures and practical instructions in Troy, laying the foundation as a result of his work, of the Lyceum of Natural History. In 1820 and 1821, Eaton initiated geological and agricultural surveys of Albany and Rensselaer counties at the expense of Van Rensselaer. Eaton's efforts led Troy as a depository of an extensive collection of geological specimens and comprehensive land surveys.

Rensselaer School

After co-founding the Rensselaer School in 1824, Van Rensselaer appointed Eaton to teach chemistry, experimental philosophy, geology, surveying, and the "laws regulating town officers and jurors."[3] By then Eaton was a well established public speaker on natural philosophy, touring and delivering lectures in the northeast. He was also a recognized pioneer in botany and principal land surveyor in the country.[5] Eaton immediately set about to develop a new kind of institution devoted to the application of science to life, to a modern scientific prospectus, to new methods of instruction and examination, to recognize women in higher education a possibility, and to be practical in training for adults. Eaton's original aim was to also train teachers and disciples, which he did in large numbers.[10] Students learned by doing, in sharp contrast with the conventional method of learning by rote. Students were made into experimenters and workers, and, in place of recitations, delivered lectures to one another. Eaton also often led day excursions, taking students to observe the application of science on nearby farms and in workshops, tanneries, and bleaching factories. They then returned to the laboratory, analyzing the principles involved. This, too, was an innovation, as it represented a reversal of the usual pedagogical method, which began with the principle and proceeded to the application.[13] Eaton's principal focus was the training of students to teach science and its applications to the New York farming community via experimental demonstrations, a goal in keeping with Britain's mechanics' institutes and lyceum movements on diffusing useful knowledge. As a result, Eaton's system of instruction posed a challenge, if not a threat, to the traditional liberal-arts colleges, causing them to expand their own curricula and set up departments or schools of engineering and science.[3] Formal engineering education would not be added at Rensselaer until 1828. After becoming professor of natural history at Harvard University in 1842, Asa Gray required some practical work of all of his students in botany along the lines established by Amos Eaton.[10] Under his leadership, Troy, New York rivaled London, England as a center for geological studies in the first part of the 19th century.

Eaton was interested in education for women, he had lectured them on his tour of New England, and he was persuaded that their failure in science was caused by inferior opportunity, not "perversion of female genius." Eaton, clearly hoped to educate females at the school. He believed that women were capable of learning practical science and mathematics; they simply had not been taught the subjects at traditional female academies. His commitment to the cause led Eaton to enroll a class of eight young women in a special mathematics course to show that they could advance beyond "the speculative geometry and algebra as generally practiced in female seminaries." When the students completed their course of study in 1835, Eaton requested a review of their progress by the school's less-than-enthusiastic board of examiners.[14] The eight young ladies who participated in Eaton's experiment continued their education at the Troy Female Seminary. Eaton trained a bevy of future, notable, scientists and lectured to countless later educationists.

Today Amos Eaton Hall houses the mathematics department, and the Amos Eaton Professorship is a faculty endowment named at the institute. The Amos Eaton Chair was originally given by students to Amos Eaton in 1839, but was later returned to the institute by the Eaton family.

Personal life

Following the death of his first wife, Polly Thomas, Eaton was remarried to Sally Cady in 1803, who bore him five sons. After her death he was remarried to Anna Bradley in 1816, by whom he had three sons and two daughters. She having died, Eaton married Alice Johnson in 1827, who bore him one son, and survived him about four years. Three of his children showed a preference for natural philosophy. Hezekiah Hulbert Eaton (1809-1832) became a chemist at Transylvania University but died at the age of twenty-three.[15] Major General Amos Beebe Eaton (1806-1877) was a U.S. Army officer interested in natural philosophy. Sara Cady Eaton (1818-1881) taught natural sciences and modern languages in a young woman's seminary at Monticello, Illinois. Eaton's grandson, Daniel Cady Eaton (1834-1895), professed botany at Yale College in the 1860s.[16]

Children

Works

Amos Eaton published on agriculture, botany, engineering, geology, surveying, and zoology.

- Art without Science (1800)

- Elementary Treatise on Botany (1810)

- Botanical Dictionary (1817) (2nd 1819, 4th ed. 1836)

- Manual of Botany (1817)

- Index to the Geology of the Northern States (1818)

- Geological and Agricultural Survey of the County of Albany, New York (1820)

- Chemical Notebook (1821)

- Chemical Instructor (1822)

- Cuvier's Grand Division (1822)

- Geological Nomenclature of North America (1822)

- Zoological Syllabus and Notebook (1822)

- Geological and Agricultural Survey of the District adjoining the Erie Canal (1824)

- Philosophical Instructor (1824)

- Botanical Exercises (1825)

- Botanical Grammar and Dictionary (1828)

- Geological Text-Books Prepared for Popular Lectures on North American Geology (1830)

- Directions for Surveying and Engineering (1838)

- Geological Text-Book for the Troy Class (1841)

Eaton's students

- James Curtis Booth — chemist, melter and refiner at the U.S. Mint

- Ezra S. Carr — medical doctor, natural scientist

- George Hammell Cook — state geologist of New Jersey and vice-president of Rutgers College

- James Dwight Dana — Geologist, zoologist

- James Eights — Antarctic explorer

- Ebenezer Emmons — geologist; named the Adirondack Mountains

- Asa Fitch — natural historian and entomologist

- Asa Gray — botanist

- James Hall — First New York State Geologist

- Joseph Henry — Developed electromagnetism

- Eben Norton Horsford — scientist

- Douglass Houghton — doctor, chemist, geologist

- Mary Mason Lyon — founder of Mount Holyoke Female Seminary

- Almira Hart Lincoln Phelps — natural scientist and educator

- John Leonard Riddell — botanist, geologist and author

- Abram Sager — professor of zoology, botany, obstetrics, and physiology

- John Torrey — botanist

- Emma Willard — founder of Troy Female Seminary

Offices held

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by NA |

Senior Professor of Rensselaer School (Rensselaer Institute from 1834) 1824-1842[11]:p. 114 |

Succeeded by George Hammell Cook |

Bibliography

- Duane Isely, One hundred and one botanists, Iowa State University Press (1994), p. 143-144

- Ray Palmer Baker, A Chapter in American Education: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1824-1924., Charles Scribner's Sons: NY(1924).

- Palmer C. Ricketts, History of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1824-1934. John Wiley & Sons: NY (1934, Third Edition).

- Amos Eaton, John Batchelder, and Stephen Williams lectures on medical jurisprudence. 1821-1824. Located in: Modern Manuscripts Collection, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD; MS C 326.[18]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ballard, Harlan Hoge (1897). Amos Eaton. Pittsfield, Massachusetts: Press of the Sun Printing Company. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ↑ Reynolds, Terry S. (1992). "The Education of Engineers in America before the Morrill Act of 1862". History of Education Quarterly. 32 (4): 459–482. doi:10.2307/368959. JSTOR 368959.

- 1 2 3 4 Gillett, Margaret (1962). "Discovery of an Unlost Letter: The Beginning of an Epoch in American Higher Education". Journal of Higher Education. Ohio State University Press. 33 (4): 200–206. doi:10.2307/1978187. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ↑ Ricketts, Palmer C. (1914). History of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute: 1824-1914. New York: J. Wiley & Sons. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- 1 2 Youmans, William Jay (1896). Pioneers of Science in America: Sketches of Their Lives and Scientific Work. New York: D. Appleton and Company. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ↑ Smallwood, William Martin (1937). "Amos Eaton, Naturalist". New York History. 18: 167–188. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ↑ Good, H. G. (1941). "Amos Eaton (1776-1842)". Scientific Monthly. 53: 464–469.

- ↑ McAllister, E. M. (1941). Amos Eaton: Scientist and Educator (1776-1842). Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ↑ Rezneck, S. (1971). In Charles Coulston Gillispie [ed.], Dictionary of Scientific Biography, volume 4. NY: Scribner & Sons.

- 1 2 3 4 Rudolph, Emanuel (1996). "History of the Botanical Teaching Laboratory in the United States". American Journal of Botany. 83 (5): 661–671. doi:10.2307/2445926. JSTOR 2445926.

- 1 2 Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (1887). Biographical Record of the Officers and Graduates of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1824-1886. Troy, NY: W.H. Young. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

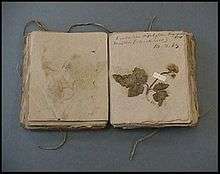

- ↑ Merrill, E. D. (1946). "The Amos Eaton Herbarium". Rhodora. New England Botanical Club, Inc. 48 (573): 201–205. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ Brubacher, J. S.; Rudy, W. (1997). Higher education in transition: A history of American colleges and universities. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction.

- ↑ "RPI Women: Beginnings 1824 to 1835". RPI.edu. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ↑ Stuckey, Ronald L. (1978). "SCIENTIFIC CONTRIBUTIONS OF AMOS EATON'S SON HEZEKIAH HULBERT EATON". Bartonia. Philadelphia Botanical Club. 45: 37–48. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ↑ "Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History: Daniel Cady Eaton". Yale.edu. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ↑ IPNI. Eaton.

- ↑ "Amos Eaton, John Batchelder, and Stephen Williams lectures on medical jurisprudence 1821-1824". National Library of Medicine.

Further reading

- Ballard, Harlan Hoge (1897). Amos Eaton. Pittsfield, Massachusetts: Berkshire Historical and Scientific Society.

- "Amos Eaton Papers, 1797-1846 (finding aid)". New York State Library Website. New York State Library. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- Spanagel, David I. DeWitt Clinton and Amos Eaton: Geology and Power in Early New York (Johns Hopkins University Press; 2014) 288 pages

External links

- "The Amos Eaton Exhibit-Biography".

- An index to the geology of the northern states (1818) - full digital facsimile at Linda Hall Library

- A botanical dictionary