Architect-led design–build

Design-build construction methods, where the designer and constructor are the same entity or are on the same team rather than being hired separately by the owner, began to make a resurgence in America at the end of the twentieth century. Most of these design-build projects were and are led by the contractor, who hires an architect to design its building, which the contractor then builds for its client, the owner.

More recently, some architects have begun to embrace a lead role in the design-build approach. They contract with the owner both to design and to construct a building, and they procure the construction services either by subcontracting to a general contractor or by contracting directly with the various construction trades. Ironically, although the notion of an architect leading a design-build team is considered new and innovative, it is really a return to the construction approach employed for the millennia prior to the twentieth century, in which the architect was the Masterbuilder, rather than merely the designer.

The following definition describes, assesses and compares the architect-led design–build (ALDB, sometimes known as designer-led design–build) process to other, related architectural project delivery methods. It focuses on the architect's role in each method, and characterizes that role in terms of responsibility. Responsibility is interpreted in terms of how much direct contact with the client (building owner) and how much control over the project the architect has, and how much risk the architect bears. The architect's role and responsibilities may change in function of the geopolitical location of the development and other criteria.

This definition of ALDB outlines the broader context of design–build, presenting that as an alternative to the traditional design–bid–build process for making buildings. First, this traditional process is introduced, then the distinct forms of design–build are explained, and from there, the focus narrows to examine specific forms of the architect-led design build method, what distinguishes it, the benefits and limitations, the results that it can achieve.

Introduction and context

Traditional design–bid–build projects

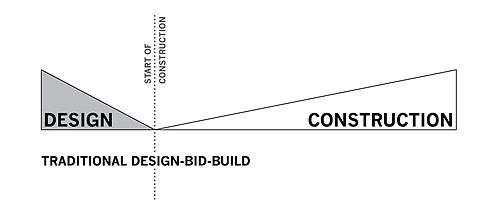

Of various approaches to making buildings, the traditional design–bid–build process is one in which a building owner hires an architect to design a building and provide a complete set of design and construction documents (drawings); a pool of general contractors bid to deliver the project's construction; the architect is hired by the building owner to aid in selecting a general contractor from those bidding on the job; the architect's set of stamped, completed and approved plans are handed off to the contracted GC, to establish a contractual agreement which binds the contractor to build the building exactly as shown in the drawings, approved plans / blue prints. From the plans/blue prints and under the GC's supervision, the project is built.

The traditional design–bid–build approach remains suitable for many projects, and where the architect remains in control of the project and beyond the design phase to supervise construction fully, or otherwise, it is definitely preferable. It is also comprehensively governed and endorsed by the American Institute of Architects.

The architect's role in traditional design–bid–build

This sequential process separates design and construction into independent tasks. Furthermore, the owner's two contracts – the first with the architect and the second with the general contractor – sets up discrete teams of specialists. Each may take too narrow a view of the whole, and if, with respective responsibilities unclear, tasks overlap or are overlooked, the parties' relationship can become more adversarial than collaborative. Fear of the resulting litigation that often targets the architect can drive architects to absent themselves from the hurly-burly of the construction process. If less involved on site, the architect may lose opportunities to inform construction, as an advocate for the client's vision and as a steward of the original design intent. Not only does this handover of responsibility diminish the architect's standing, the lack of continuity may also compromise the quality of the project outcomes.

Design–build as an alternative to design–bid–build

- Dynamic: Design–build (or Design/Build, D-B or D/B, or 'DB') is a construction project delivery system in which the designer and constructor are teamed together (or are a single entity) rather than each being hired separately by the owner or developer. If teamed together, the designer and constructor may be in a joint business venture, or one may be the subcontractor of the other.

- Efficient: Typically led by contractors, 'design–build' has evolved as an efficient way to deliver projects primarily where the building project goals are straightforward, either constrained by budget, or the outcome is prescribed by functional requirements (for example, a highway, sports facility, or brewery). Construction industry commentators have described design–build as a high performance 'construction project delivery system', a dynamic approach to making buildings that presents an alternative to the traditional design-bid-build approach.

- Single-source: Design–build is growing because of the advantages of single-source management: Unlike traditional design-bid-build, it allows for the owner to contract with just one party who acts as a single point of contact, is responsible for delivering the project and coordinates the rest of the team. Depending on the phasing of the project, there may be multiple sequential contracts between the owner and the design–builder. the owner benefits because if something turns out to be wrong with the project, there is a single entity that is responsible for fixing the problem, rather than a separate designer and constructor each blaming the other.

Not all design–build projects are alike.[1] Here, there is a distinction between design–build projects led by contractors and those led by architects. Architect-led Design Build is a form of 'design–build' that, according to the DBIA,[2] has been rapidly gaining market share in the United States over the past 15 years. The Design Build Institute of America describes the design–build process as follows:

Taking singular responsibility, the design–build team is accountable for cost, schedule and performance, under a single contract and with reduced administrative paperwork, clients can focus on the project rather than managing disparate contracts. And, by closing warranty gaps, building owners also virtually eliminate litigation claims.

The DBIA's 2005 chart shows the uptake of design–build methods in non-residential design and construction in the United States.[3]

Architect-led design–build is sometimes known by the more generic name "designer-led design–build". Although employed primarily by architects, architectural technologists and other architectural professions, the design–build structure works similarly for interior design projects led by an interior designer who is not an architect, and also for engineering projects where the design–build team is led by a professional structural, civil, mechanical or other engineers. In addition, it is common for the design professional who leads the design–build team to create a separate corporation or similar business entity through which the professional performs the construction and other related non-professional services.

Design–build continues to gain ground as a significant trend in design and construction today.[4]

In March 2011, industry consultants ZweigWhite published "Design-Bid-Build meets the opposition".[5] In it, they suggest that while Design-Bid-Build "still rules", the traditional approach is losing favor as "alternative project delivery methods threaten [the] design-bid-build model." While not referencing the architect-led design–build approach specifically, the article states that D/B already accounts for 27% of projects, according to their 2010 Project Management Survey and goes on to argue that,

The emerging trends in delivery seem to point to a return to the primordial concept of the masterbuilder, as exemplified by D/B and IPD [Integrated Project Delivery].

Design–build workflow

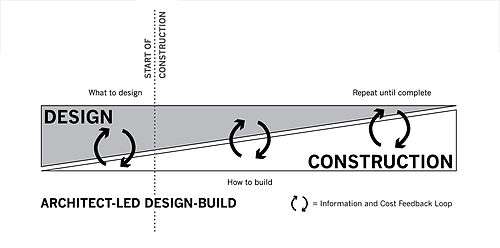

The dynamic architect-led design–build workflow reintroduces discursive coordination, collaboration and consistent, reflexive managerial oversight over the arc of a project schedule, maximizing project efficiency (time, cost, functionality) without compromising design performance or the quality of project outcomes. Design–build can be an iterative and dynamic method, reflecting an emergent design process in which decisions are made holistically and progressively refined as interdependencies are prioritized, identified and coordinated.

Contractor-led design–build projects: the architect's role

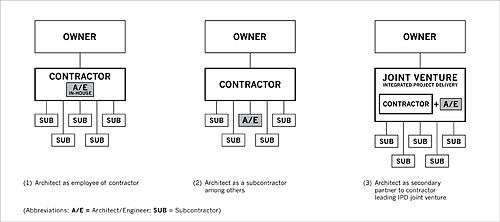

On contractor-led design–build projects, management is structured so that the owner works directly with a contractor who, in turn, coordinates subcontractors. Architects contribute to contractor-led design–build projects in one of several ways, with varying degrees of responsibility (where "A/E" in each diagram represents the architect/engineer):

(1) Architect as employee of contractor

The architect works for the contractor as an in-house employee. The architect still bears professional risk and is likely to have less control than in other contractor-led design–build approaches.

(2) Architect as a subcontractor

Here, the architect is one of the many subcontractors on the team led by the contractor. The architect bears similar professional risk but still with little control.

(3) Architect as second party in contractor-led integrated project delivery (IPD)

The architect and contractor work together in a joint venture, both coordinating the subcontractors to get the project built. The building owner has a single contract with this joint venture. The contractor leads the joint venture so in supervising the subs, the architect might defer to the contractor. The architect bears the same risk as they do in the traditional approach but has more control in IPD, even if they were to defer to the contractor.

Examples of contractor-led design–build projects

- Dena'ina Civic & Convention Center, Anchorage, AK, Neeser Construction, Inc.

- In 2010, it won the 2010 DBIA Design Build Merit Award for a public sector project over $50 million.[6]

- Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, Phoenix, AZ, Ehrlich Architects[7][8][9]

- In 2009, it won the 2009 DBIA National Design Build Award for a public sector project over $25 million.[10]

Projects

Architect-led design–build projects are those in which interdisciplinary teams of architects and building trades professionals collaborate in an agile management process, where design strategy and construction expertise are seamlessly integrated, and the architect, as owner-advocate, project-steward and team-leader, ensures high fidelity between project aims and outcomes. In architect-led design–build projects, the architect works directly with the owner (the client), acts as the designer and builder, coordinating a team of consultants, subcontractors and materials suppliers throughout the project lifecycle.

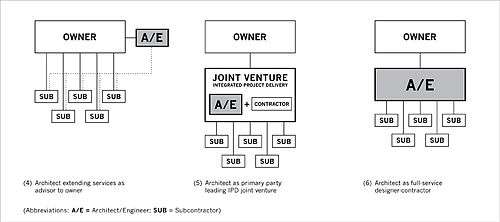

Architects lead design–build projects in several ways, with varying degrees of responsibility (where "A/E" in each diagram represents the architect/engineer):

(4) Architect as provider of extended services

Contracted to the owner, the architect extends his or her services beyond the design phase, taking responsibility for managing the subcontractors on behalf of the owner. The architect bears similar risk but has more control over the project than in the traditional approach or on contractor-led design–build projects.

(5) Architect as primary party in architect-led integrated project delivery (IPD)

Again, as in (C) above, the architect and contractor work together in a joint venture, both coordinating the subcontractors to get the project built. Again, the building owner has a single contract with this joint venture. This time, the architect leads the joint venture so in supervising the subs, the contractor might defer to the architect. The architect might bear more risk than they do in the traditional approach but risk is shared with the owner and the contractor, as outlined in their agreement. An alternative approach to effectuating this delivery structure is for the architect to contract directly with the owner to design and build the project, and then to subcontract the procurement and construction responsibilities to its allied general contractor, who enters into further subcontracts with the trades. This is a difference in form, rather than in substance, because the business and legal terms of the agreement between the architect and the general contractor may be the same regardless of whether they are characterized as a joint venture or as a subcontract. It is the "flip side of the coin" of the contractor-led approach described above in which the general contractor subcontracts the design to the architect.

(6) Architect as full service leader of design build process

Contracted to the owner, the architect offers full service to the owner, taking responsibility for managing the subcontractors, consultants and vendors, and involving them throughout the project, start to finish, from design through construction. The architect's role shifts during the project, from designer to site supervisor (effectively taking the role of a general contractor), but monitors the project vision, and is able to call upon subcontractors' construction expertise throughout. The architect bears the greatest risk but also has more control over the project than in either the traditional approach, or in the contractor-led and other architect-led design–build projects.

Workflow

In design–build projects led by architects, the architect has the opportunity to lead the team through progressive iterations during the design–build process instead of producing sequential, schematic, design, construction drawings and construction administration documents. These continuous feedback loops extend the phase in which the team is dedicated to producing the most informed design. Each iteration is progressively informed by budgets, continuously improving information and the best efficient construction techniques.

The architect≠client relationship renegotiated

Together, client and architect can prioritize their decisions so choices can be made when the relevant information for making decisions is actually available. This is in contrast to the typical process in which architects are constrained to make speculative choices without accurate cost or technical information, and clients are invited to make decisions only at review milestones.

Here, the architect is able to co-design with the client in an ongoing exchange throughout a project, so the client retains more influence over the design, and once on site, is a more informed stakeholder during construction. This way, architect-led design–build can be co-creative, and the most appropriate project outcomes can emerge from this active dialogue between clients, designers and fabricators. The process allows clients the opportunity to participate with full transparency in the financials of the project throughout its time-line.

Over the arc of a building project, the architect's strategic leadership role remains constant but their tasks may vary from:

- Discovering and prioritizing client's requirements (functional, aesthetic, budget, schedule) to

- Identifying contextual constraints (technicalities of site, materials, construction methods, neighborhood/cultural mindset, historical meaning)

- Synthesizing both to define initial parameters and set project direction to assume the best and most complete architectural expression

- Generating a preliminary design response

- Drafting documentation for that design that invites and facilitates continuous client and consultant feedback

- Managing the financials and assuming full fiduciary responsibility over the course of the project with full client transparency

- Refining progressive iterations of a design from both design and construction perspectives until an optimal outcome, appropriate to the project goals, emerges.

- Preparing actionable, legible drawing sets that reflect construction-ready and trade-specific details for each trade to refer to, under architect's supervision, on site – and publishing these at the appropriate time in the process of construction.

Reintegrating practice, towards a modern architecture

Throughout an architect-led design–build project, design and construction considerations are inextricable from each other until each are optimized. This design–build approach allows for a dynamic, recursive process rather than a linear one, for construction expertise early and design expertise late. So, rather than designing-then-building, architect-led design–build works like this:

Key features

Challenging the split between design and construction

- In the master–builder relationship, design and construction tasks were considered inextricable from one another. From the mid-twentieth century on, design and construction contracts, activities and roles were separated from one another as projects became more complex. In response to this complexity, increasingly specialized roles, silo'd by skill, and project management shaped by litigation and risk management, deepened this split.

- The architect-led approach challenges this "Balkanization" of the building profession, successfully, respectfully, comprehensively reintegrating design and construction tasks and reuniting architecture and construction professionals.

- The architect leading these complex design–build projects acknowledges that the client requires interdisciplinary – not just multi-disciplinary – teams of properly coordinated, varied specialists to deliver, and these cross-functional teams require active management to collaborate effectively.

Better business

In architect-led design–build projects, the leading architect:

- Serves the owner directly, rather than through the contractor

- Respects the contractors' craft expertise and time

- Facilitates a profitable project for all

- Reclaims his or her own value, and draws on knowledge from a project to feed it back to the profession

- Facilitates as the "conductor of a work or symphony with only a single performance", advocating the owner's vision, maximizing the subcontractors' construction expertise and brokering the two.

Above all, the architect leading the design–build project empowers the architects and contractors to produce better, cost effective, higher quality, context-sensitive, high performance buildings. How? By comprehending, prioritizing, and designing according to specific relationships between scope, quality and time, and by optimizing cost to program.

So by inviting architects to lead, design–build methods give architects a platform for advocating clients, respecting craftsmanship and reasserting the value of architects' expertise, improving the built environment, and for doing better business. The more functional and less fearful the architect's business, the more attention they can pay to producing high quality design outcomes.

Generating unique outcomes by replicable methods

Consistent and recursive, the design–build process can generate unique, high quality buildings that improve and optimize the broader built environment and work for and are tailored to clients beyond the construction schedule, within specific budgetary, scheduling and site constraints. By removing impediments mostly ascribed to aggressive risk management, the approach broadens the scope for greater architectural creativity. This way, outcomes are more likely to respond to functionality, synthesize context, social intent and artistic sensibility.

Appropriate and successful application across a broad range of projects

Architect-led design–build is suited primarily to less prescriptive architectural projects (private residences, non-profit institutions, museums), for the efficiencies it yields and the sophisticated design interpretation it affords, particularly:

- Where the primary project goals are design-driven or visionary rather than prescribed by budgetary constraint or functional requirements

- Where the project is specifically "Capital A"-artistically/creatively driven, in a way that traditionally yields the highest level of cost overruns.

- Where the efficiencies of design–build approach and an architect's interpretive skill are equally important

These less prescriptive projects need not be stuck with the "broken buildings and busted budgets"[11] described by Barry Lepatner. Rather, the less prescriptive the project, the more the client needs an architect to steward an emergent design from vision to completion. So it follows that for the broadest range of building projects, the rigors of architect-led design–build is compelling and preferable where design is of paramount importance to the client.

Unifying strategy and practice

The Architect-led design build process synthesizes strategy and craft, so project outcomes cohere with client objectives. Connecting problem-solving ('brains on' design activities) to physical outcomes ('hands on' construction activities), as vernacular architecture and grand industrial crafts-led architecture have both done, the architect-led design–build approach assumes that design decisions are informed and improved by knowledge of fabrication options, tools and techniques, and that construction will more likely match a client's project objectives if it follows an overall design intention. It is not a nostalgic endeavor but a reclamation of thinking and making, a reintegration after mid-twentieth century specialization.

Flexible

A design–build process led by an architect can be open, consistent, tolerant to inevitable or necessary changes during construction. Transparent to all participating consultants, it demystifies the decision-making process for clients. As co-creators, clients' input informs design as it happens, not just during the design phase. In exchange, architects leading a design build process maintain oversight of what gets built on behalf of clients, rather than ceding control to contractors.

Generating recursive knowledge

The process and the knowledge it produces is recursive: Since subcontractors are engaged early and often in an architect-led design build project, to assess efficiencies, opportunity costs, payback rates and quality options. Their input informs overall design decisions from the outset. Cost-benefit is also a constant consideration that informs design decisions from the outset. Building performance is measured early too, so that trade offs between budget, schedule, functionality and usability can inform specification and continuous refinement of the design.

Architects engaged in this dynamic process understand and keep up to date with the potential of contemporary technology[12] and materials available to building professionals, and translate what they learn into their design work. This knowledge is fed back, not just to the specific project but can be shared to other project teams, throughout a studio, or more broadly to the profession, and can become an active source of insight in and of itself.

Contracts

The architect leading the design–build project works with the client, acting as the single point of contact to a unified team of end-to-end service providers, including architects and construction trades people. The architect, as the "ALDB entity", can guarantee the price for the complete structure to cover the building owner under a single contract, determining where funds are best spent.

A single set of integrated contracts combining design and construction responsibilities, rather than two discrete contracts for each, acknowledges the interdependence of the architects' and construction trades' project responsibilities, and reduces the likelihood of disputes.

Advanced Design-Build Strategies for Architects[13] by Dorwin AJ Thomas, formerly chairman of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Design–build Knowledge Community, includes more detail on contracts for design–build projects, and further project examples.

Advantages

According to the DBIA, the design–build approach offers advantages to owners, including: "One team, one contract, one unified flow of work from initial concept through completion."[14]

Benefits to owners

- Speed of completion

- Single-point responsibility

- Greater cost savings and earlier cost certainty

- "Value Engineering" at conceptual stages rather than too late, after project design is complete

- Better communication

- Fewer disputes and litigation

- Higher quality outcomes

- Clear roles, responsibilities and accountability

- Less administrative burden

- Reduced risk to the client (because the design–build entity assumes more)

- Reduced risk to design consultants and subcontractors which results in lower construction costs, greater efficiencies and fewer litigation claims.

Benefits to practitioners

- Control over costs

- Streamlined team communication, so less administration, fewer litigation claims, greater market share as more owners choose this approach.

Overall benefits

Design–build architects learn from experience in a dynamic, live process during an evolving project, to achieve design goals and yield authentic outcomes: From experience, they are able to work with placeholders, anticipating when to defer design decisions and trusting that as open-ended options become limited and details more precise, a robust, appropriate authentic design can and will emerge. In this sense, design–build is as much an art as it is a tried and trusted methodology.

- Owners remain involved and therefore are able to contribute throughout their projects. Because of process they are able to make informed decisions at the opportune times, which results in better buildings that meet their needs in meaningful ways.

- Subcontractors are respected as team-members, and can perform their work more efficiently, effectively and profitably. Unknowns in their work are reduced so that they are better positioned to be financially successful.

- Architects regain control, assert their value in making buildings, ensuring their designs are realized

- Architects gain and share knowledge in their community of practice

- Conflict is reduced or resolved at low cost

- Costs and quality are controlled

- As more "trouble free" high quality buildings are bid, architects will gain respect and have more impact on the American built environment.

Limitations and constraints

Advocates of architect-led design build[13][15][16] also offer critiques of the approach, highlighting:

- Issues that an architect-led approach to design–build still does not overcome:

- Typical project management issues (establishing liability, writing contracts, scoping estimates and schedule) or

- Variation across different states' licensing laws or

- Conflict of interest and ethical issues

- Where architect-led design–build imposes:

- Greater business and financial risks associated with architect taking on general contractor responsibilities

- Changes to the way architects do business, so they

- Establish a construction company as a separate corporation that signs a separate construction contract, so they are able to insure and simplify liability insurance coverage

- Either they have, or are able to acquire, the skills of a design–builder

- Recognize the parties' different incentives

- Modify how they prepare Contract Documents, relying more on performance specifications than they do currently, to facilitate substitutions for the benefit of the constructor.

See also

References

- ↑ Hopes and Fears of Design–build, Nancy Solomon, Architectural Record, November 2005

- ↑ Design Build Institute of America, or DBIA

- ↑ What is Design Build? Archived May 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Architects Should Be Leading Design-build Projects, by Luis Jauregui Residential Design Build magazine, October 2010 Archived February 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The Zweig Letter, ISSN 1068-1310, issue 902

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ↑ Walter Cronkite School of Journalism, Phoenix, by Sam Lubell, Architect magazine, July 30, 2009

- ↑ Cronkite Communication School Speaks to Phoenix Redevelopment, by Jay W. Schneider, Building Design and Construction, August 14, 2009

- ↑ Walter Cronkite School of Journalism, case study by Scott Blair, Greensource magazine, September 2010 Archived April 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- ↑ LePatner, Barry. "Broken Buildings, Busted Budgets: How to Fix America's Trillion-Dollar Construction Industry". The University of Chicago Press, 2007.

- ↑ An Enthusiastic Sceptic by Nat Oppenheimer, Architectural Design (2009) Volume: 79, Issue: 2, Pages: 100–105, an assessment of Building Information Management (BIM) software

- 1 2 Advanced Design-Build Strategies for Architects by Dorwin A.J. Thomas, DBIA Archived March 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2011-03-23."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-08-22. Retrieved 2012-08-22.

- ↑ AIA Teaching Architects To Lead Design-Build Teams by Tom Nicholson, Design and Construction, May/June 2005

- ↑ "Designer-led Design-Build" by Mark Friedlander, Schiff Hardin Archived October 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

Further reading

- "A New Solution For Public Construction Projects: Sequential Designer-Led Design-Build", by Mark Friedlander

- "Design-Build and Integrated Project Delivery: Narrowing the Gap" American Institute of Architects (AIA), issue 21, August 21, 2009

- When Is Hiring Professionals Worth It? The Bottom Line: It Depends.; Architects vs. Contractors vs. Design-Build Firms . . . There Are Several Options and No Easy Answers, by Denise DiFulco, The Washington Post, July 17, 2008

- 'Design-Build' Trend Sweeps Redo Market; 2-Step Approach Unites Architects, Contractors by Ann Marie Moriarty, The Washington Post, March 27, 2002

External links

Examples of projects

- The East Harlem School, New York, Peter Gluck and Partners, Architects

- East Harlem School, gallery, Architype Review Vol. 4 No. 3

- East Harlem School, New York, description, Architype Review Vol 4 No.3

- East Harlem School, dialogue with Peter Gluck, architect, Architype Review Vol 4 No.3

- The Pride of E103rd Street, by Suzanne LaBarre, Metropolis magazine, January 13, 2010

- The East Harlem School at Exodus House, feature, Urban Omnibus, February 2010

- The Vienna Way House, Marmol Radziner, Architects