Battle for Caen

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

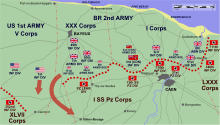

The Battle for Caen from June–August 1944 was a battle of the Second World War between Allied forces of the mainly Anglo-Canadian Second Army and German forces of Panzergruppe West during the Battle of Normandy. The Allies aimed to take Caen, one of the largest cities in Normandy on D-Day. Caen was an important Allied objective because it lay astride the Orne River and Caen Canal; these two water obstacles could strengthen a German defensive position if not crossed. Caen was a road hub and the side which held it could shift forces rapidly. The area around Caen was open, compared to the bocage country in the west of Normandy and was valuable land for airfields.

On D-Day, 6 June 1944, Caen was an objective for the 3rd British Infantry Division and remained the focal point for a series of battles throughout June, July and into August. The battle did not go as planned for the Allies, instead dragging on for two months, because German forces devoted most of their reserves to holding Caen, particularly their armoured divisions. As a result, German forces facing the American invasion thrust further west were spread thin, relying on the rough terrain of the back country to slow down the American advance up to Operation Cobra. With so many German divisions held up defending Caen, the American forces were eventually able to break through to the south and east, threatening to encircle the German forces in Normandy from behind. The old city of Caen—with many buildings dating back to the Middle Ages—was destroyed by Allied bombing and the fighting. The reconstruction of Caen lasted until 1962; today, little of the pre-war city remains.

Background

Operation Neptune

On 6 June 1944, Allied forces invaded France by launching Operation Neptune, the beach landing operation of Operation Overlord. A force of several thousand ships assaulted the beaches in Normandy, supported by about 3,000 aircraft. The D-Day landings were successful, but the Allied forces were unable to take Caen as planned. The Allies also employed airborne troops. The US 82nd Airborne Division and US 101st Airborne Division, as well as the British 6th Airborne Division (with the attached 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion), were inserted behind the enemy lines. The British and Canadian paratroopers behind Sword Beach were tasked in Operation Tonga with reaching and occupying the strategically important bridges such as Horsa and Pegasus, as well as to take the artillery battery at Merville to hinder the forward progress of the German forces. They managed to establish a bridgehead north of Caen, on the east bank of the Orne, that the Allied troops could use to their advantage in the battle for Caen. The first operation intended to capture Caen was the initial landings on Sword Beach by the British 3rd Infantry Division on 6 June. Despite being able to penetrate the Atlantic Wall and push south the division was unable to reach the city, their final objectives according to the plan, and in fact fell short by 3.7 mi (6.0 km). The 21st Panzer Division launched several counter-attacks during the afternoon which blocked the road to Caen.

Battle

Operation Perch

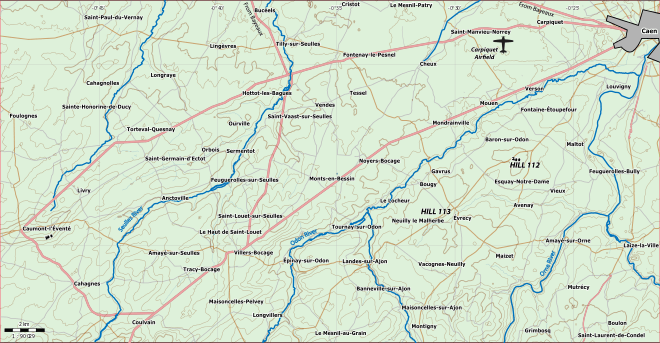

Operation Perch was the second attempt to capture Caen after the direct attack from Sword Beach on 6 June failed. According to its pre-D-Day design, Operation Perch was intended to create the threat of a British break-out to the south-east of Caen.[1] The operation was assigned to XXX Corps; the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division was tasked with capturing Bayeux and the road to Tilly-sur-Seulles.[2][3] The 7th Armoured Division would then spearhead the advance to Mont Pinçon.[3][4] On 9 June, General Bernard Montgomery, commander of all ground troops in Normandy, ordered that Caen be taken by a pincer movement.[5] The eastern arm of the attack would consist of I Corps's 51st (Highland) Infantry Division. The Highlanders would cross into the Orne bridgehead, the ground gained east of the Orne during Operation Tonga, and attack southwards to Cagny, 6 mi (9.7 km) to the southeast of Caen. XXX Corps would form the pincer's western arm; the 7th Armoured Division would advance east, cross the Odon River to capture Évrecy and the high ground near the town (Hill 112).[1][6]

Over the next few days, XXX Corps battled for control of the town of Tilly-sur-Seulles, defended by the Panzer-Lehr Division and elements of the 12th SS Panzer Division; the Allied forces became bogged down in the bocage, unable to overcome the formidable resistance offered.[7][8][9] I Corps were delayed moving into position, so their attack was rescheduled for 12 June.[6] When the 51st Highland Division launched its attack, it faced stiff resistance from the 21st Panzer Division in its efforts to push south; with the Highlanders unable to make progress, by 13 June the offensive east of Caen was called off.[10]

On the right flank of XXX Corps, the Germans were unable to resist American attacks and began to withdraw southwards, which opened a 7.5 mi (12.1 km) gap in the German front line.[4][11] Conscious of the opportunity presented, Miles Dempsey, British Second Army commander, ordered the 7th Armoured Division to exploit the opening in the German lines, seize the town of Villers-Bocage and advance into the western flank of the Panzer-Lehr Division.[12][13][14] After the Battle of Villers-Bocage, the position was judged untenable and 7th Armoured Division was withdrawn on 14 June.[15][16] The division was reinforced by the 33rd Armoured Brigade, which was landing in the beachhead.[17][18] It was planned that the reinforced division would resume the attack, but on 19 June, a severe storm descended upon the English Channel damaging the two Mulberry harbours and causing widespread disruption to beach supply operations, and further offensives were abandoned.[17][19]

Le Mesnil-Patry

The last big Canadian operation in June was directed at gaining high ground to the south-west of Caen, in support of attacks further west by the 50th (Northumbrian) Division and 7th Armoured Division. No. 46 Royal Marine Commando, Canadian tanks and Le Régiment de la Chaudière, advanced to Rots. An attack on 11 June by The Queen's Own Rifles and tanks of the 1st Hussars (6th Canadian Armoured Regiment) was repulsed at Le Mesnil-Patry by troops of the 12th SS-Panzer Division, which had been preparing a counter-attack. The attack had been planned for the early hours of 12 June, but was brought forward to 2:30 p.m. on 11 June.[20][21]

The Canadian column advanced, with B Squadron of the 1st Hussars in the lead, with men of D Company of the Queen's Own Rifles riding on the 1st Hussar tanks.[21] Panzergrenadiers and tanks of the 12th SS-Panzer Division ambushed B Squadron in a grain field near Le Mesnil-Patry, having gleaned information from Hussar radio traffic, after capturing wireless codes from a destroyed Canadian tank on 9 June. Canadian infantry riding on the tanks jumped off or were thrown off the tanks, which were hit and engaged the SS-Panzergrenadiers in the wheat fields as the surviving tanks pushed on into the village.[22] The commander of the lead element of the Hussars, Lieutenant Colonel Colwell, ordered a retreat, but the order was not heard by B Squadron. Using Panzerfausts, Panzerschrecks and anti-tank guns, the Germans knocked out 51 of the 53 Shermans and inflicted casualties of 61 killed or missing, 2 wounded and 11 captured from the vanguard of the 1st Hussars. The Queen's Own Rifles suffered 55 killed, 33 wounded and 11 taken prisoner during the attack.[21] An English newspaper called it the modern equivalent of the Charge of the Light Brigade.[22] The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division assumed a static role until Operation Windsor in the first week of July.[23]

Operation Martlet

Operation Martlet (also known as Operation Dauntless) was a preliminary attack to support Operation Epsom was launched on 25 June by the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division and the 8th Armoured Brigade of XXX Corps.[24] The objective was to secure ground on the right flank of VIII Corps. During Epsom, VIII Corps would be endangered by the German forces on the Rauray Spur to the west, a ridge that overlooked the line of advance of 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division. The spur and the villages of Rauray, Fontenay-le-Pesnel, Tessel-Bretteville, and Juvigny were to be taken by the 49th Division and the 50th Division was to advance southwards from Tilly. Opposing the British were the 3rd Battalion, 26th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment and elements from the 12th SS Panzer Regiment of 12th SS Panzer Division, stationed on and around the spur. Both had been depleted by the fighting in the preceding weeks, but were well dug-in.[25]

By the afternoon of 25 June, the 43rd Division had reached its objective line at the woods near Vendes.[26] By midnight, the 49th Division established a line roughly south of Fontenay-le-Pesnel. Rauray and around half of the spur remained in enemy hands. At 5:30 a.m. on 26 June, the 70th Infantry and 8th Armoured Brigades continued the 49th Division attack. A battlegroup of the 24th Lancers and the 12th (Motorised) Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps, reached Tessel-Bretteville but were withdrawn during the afternoon, as the troops on their right had been held up.[27] During the night, two companies of II/192nd Panzer-Grenadier Regiment of 21st Panzer Division reinforced the Panzer-Lehr-Division on the right flank near Vendes.[28] Then next day, the 146th Brigade captured Tessel-Bretteville wood and the 70th Infantry Brigade–8th Armoured Brigade battlegroup reached Rauray, which was captured by nightfall.[29]

Early on 28 June, the 70th Brigade attacked towards Brettevillette, but counter-attacks by part of Kampfgruppe Weidinger delayed the British advance until the II SS Panzer Corps arrived, retook Brettevillete and formed a new defensive line around Rauray.[29][30] From 29–30 June, the 49th Division consolidated the area around Rauray, as the main counter-attack by II SS Panzer Corps against Operation Epsom took place further south.[31] On 1 July, Kampfgruppe Weidinger attacked Rauray frontally at 6:00 a.m. The 11th Durham Light Infantry and the 1st Tyneside Scottish eventually repulsed the attack and at 10:00 a.m. the Germans withdrew. At 11:00 a.m., Kampfgruppe Weidinger attacked again, but failed to breach the British line. An attack around noon by the 9th SS Panzer Division to the south made little progress and by 6:00 p.m. the Germans withdrew, leaving about thirty knocked-out armoured vehicles behind.[32]

Operation Epsom

After a delay caused by the three-day storm that descended upon the English Channel, the Second Army launched Operation Epsom on 26 June.[33][34] The objective of the operation was to capture the high ground south of Caen, near Bretteville-sur-Laize.[35] The attack was carried out by the newly arrived VIII Corps, which consisted of 60,244 men under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir Richard O'Connor.[36] The operation would be supported by 736 artillery pieces, the Royal Navy, close air support and a preliminary bombardment by 250 bombers of the Royal Air Force.[37][38] However, the planned bombing mission for the start of the operation had to be called off due to poor weather over Britain.[39]

I and XXX Corps were also assigned to support Epsom, but delays in landing equipment and reinforcements led to their role being reduced. On the day before the attack was to be launched, Operation Martlet (also known as Operation Dauntless) was to be launched; 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division, supported by tanks, was to secure the VIII Corps flank, by capturing the high ground to the right of their advance.[24][40][40] I Corps would launch two supporting operations, several days following the launch of Epsom, codenamed Aberlour and Ottawa. The 3rd Division, supported by the 8th Canadian Brigade, would launch the former and attack north of Caen; the latter would be an attempt by the 3rd Canadian Division, supported by tanks, to take the village and airfield of Carpiquet, but the attacks were cancelled.[41]

Supported by the tanks of the 31st Tank Brigade, the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division made steady progress and by the end of the first day, had largely overrun the German outpost line, although there remained some difficulties in securing the flanks of the advance. Over the following two days, a foothold was secured across the River Odon and efforts were made to expand this, by capturing strategic points around the salient and moving up the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division. However, in response to powerful German counter-attacks by the I SS Panzer Corps and II SS Panzer Corps, some of the British positions across the river were withdrawn by 30 June; VIII Corps had advanced nearly 6 mi (9.7 km).[42] The Germans throwing in their last available reserves, had been able to achieve a defensive success at the operational level and contain the British offensive.[43] Tactically, the fighting was indecisive and after the initial gains made, neither side was able to make much progress; German counter-attacks were repulsed and further advances by British forces halted.[44]

The Second Army had retained the initiative over the German forces in Normandy, had halted a massed German counter-attack against the Allied beachhead before it could be launched and prevented German armoured forces being redeployed to face the Americans or being relieved and passed into reserve.[45] The operation cost the Second Army up to 4,078 casualties, from 26–30 June VIII Corps suffered 470 men killed, 2,187 wounded and 706 men missing. During 1 July, a further 488 men were killed and wounded and 227 were reported missing. These figures exclude formations conducting preliminary operations and attacks in support of Epsom.[46] The German Army lost over 3,000 men and 126 tanks knocked out.[47][48]

Operation Windsor

The airfield at Carpiquet near Caen was to have been taken on D-Day but German resistance prevented its capture. Many concrete shelters, machine gun towers, underground tunnels, 75 mm (2.95 in) anti-tank guns and 20 mm (0.79 in) anti-aircraft guns were around the airfield, behind mine fields and barbed wire entanglements. Operation Windsor was intended to break through the strongly held German positions near the airfield. The 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade was reinforced by the Royal Winnipeg Rifles from the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade and tanks of The Fort Garry Horse (10th Armoured Regiment) and three squadrons of specialist tanks from the 79th Armoured Division, including a flamethrower squadron. Artillery support was provided by the battleship HMS Rodney, 21 artillery regiments and two squadrons of RAF Hawker Typhoon ground support aircraft.[49]

The French Resistance had informed the Canadian troops about the defences surrounding the airfield. The Canadians took Carpiquet village on 5 July and three days later, after repulsing several German counter-attacks, took the airfield and adjacent villages during Operation Charnwood. Major-General Rod Keller, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division commander, was severely criticised for not sending two brigades into Operation Windsor and for delegating detailed planning to Brigadier Blackader of the 8th Brigade.[50] The perceived poor performance of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was seen by Lieutenant-General John Crocker, the I Corps commander, as more evidence that Keller was unfit for his command. After the performance of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division in Operation Atlantic, Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds the II Canadian Corps commander, decided that Keller should retain his command.[51]

Operation Charnwood

Three infantry divisions and three armoured brigades of I Corps were to attack southwards through Caen to the Orne river and capture bridgeheads in the districts of Caen south of the river.[52][53] An armoured column was prepared to advance through the city to rush the bridges; it was hoped that I Corps could exploit the situation to sweep on through southern Caen toward the Verrières and Bourguébus ridges, opening the way for the British Second Army to advance toward Falaise.[54][55] New tactics were tried, including a preparatory bombardment by Allied strategic bombers to assist the Anglo-Canadian advance and to prevent German reinforcements from reaching the battle or retreating.[56][57][58][59] Suppression of the German defences was of a secondary consideration; close support aircraft and 656 guns supported the attack.[55][60]

On the night of 7 July, the first wave of bombers dropped over 2,000 short tons (1,800 t) of bombs on the city.[nb 1] The attack began at 04:30 on 8 July and several hours later the final wave of bombers arrived over the battlefield.[59][65] By evening, the Allied force had reached the outskirts of Caen and the German command authorised the withdrawal of all heavy weapons and the remnants of the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division across the Orne to the southern side of Caen. The remnants of the 12th SS-Panzer Division fought a rearguard action and then retired over the Orne.[66][67]

"Mountains of rubble, [approximately] 20 or 30 feet [≈ 6 or 9 meter] high [...] the dead lay everywhere."

Arthur Wilkes describing the situation following the operation.[68]

Early on 9 July, Anglo-Canadian patrols entered the city and Carpiquet airfield was occupied after 12th SS-Panzer Division withdrew during the night.[69] By noon, the Allied infantry had reached the north bank of the Orne and inflicted many losses on the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division.[70] Some bridges were left intact but were blocked by rubble and covered by German troops on the south side of the river, ready for a German counter-attack.[71] By mid-afternoon on 9 July, Operation Charnwood was complete.[62] Following the battle "In the houses that were still standing there slowly came life, as the French civilians realized that we had taken the city. They came running out of their houses with glasses and bottles of wine.".[68]

Operation Jupiter

Operation Jupiter was a VIII Corps attack by the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division and the 4th Armoured Brigade on 10 July, the day after the conclusion of Operation Charnwood. The German defenders had five infantry battalions, two Tiger heavy tank battalions, two Sturmgeschütz companies and Nebelwerfer drawn mostly from the 10th SS-Panzer Division Frundsberg, with elements of the 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen and the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend in reserve. The attack was intended to capture the villages of Baron-sur-Odon, Fontaine-Étoupefour, Château de Fontaine and recapture the top of Hill 112 by 9:00 a.m.[72] After the first phase, positions on Hill 112 were to cover an advance on Éterville, Maltot and the ground up to the River Orne. A bombardment of mortars and over 100 field guns was to precede the attack.[73]

The German troops endured naval bombardment, air attack and artillery fire but held their ground, with support from Tiger tanks of the schwere SS-Panzer Abteilung 102 carrying 88 mm guns which out-ranged the opposing British Churchill and Sherman tanks. Hill 112 was not captured and was left as a no-man's-land between the two armies. Several villages nearby were taken and the 9th SS Panzer Division was sent from reserve to contain the attack, which achieved the Allied operational objective. (In August the Germans withdrew from Hill 112 and the 53rd (Welsh) Division occupied the feature almost unopposed. British casualties during the period were c. 25,000 troops and c. 500 tanks. The 43rd Infantry Division had 7,000 casualties from 10–22 July.)[74]

Operation Atlantic

During the Battle of Caen, the I SS Panzer Corps had turned the 90-foot (27 m) high ridge into their primary fortification, defending it with hundreds of guns, tanks, Nebelwerfers, mortars, and infantry from up to three divisions.[75] As part of a minor follow-up to Operation Goodwood, The Calgary Highlanders had managed to establish preliminary positions on Verrières at Point 67, on the northern spur of the ridge.[76] On 20 July, The South Saskatchewan Regiment, with support from The Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada and the 27th Armoured Regiment (The Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment), as well as Hawker Typhoons, assaulted the ridge.[77] The Cameron Highlanders attacked Saint-André-sur-Orne but were repulsed.[78] The main attack took place in torrential rain, rendering tanks and infantry immobile and aircraft grounded.[77] The South Saskatchewans lost 282 casualties.[79] In the aftermath of the South Saskatchewan attack, two German SS Panzer divisions counter-attacked and forced the Canadians back past their start-lines. The counter-attack also forced the supporting The Essex Scottish Regiment back. The Essex Scottish lost c. 300 casualties.[80] On 21 July, Simonds ordered The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada and The Calgary Highlanders to stabilise the front along Verrières Ridge.[81] The two battalions and the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division defeated counter-attacks by the two SS Panzer divisions in costly defensive fighting.[79]

Operation Goodwood

Operation Goodwood took place from 18–20 July 1944. VIII Corps, with three armoured divisions, attacked towards the German-held Bourguébus Ridge, along with the area between Bretteville-sur-Laize and Vimont, intending to force the Germans to commit their armoured reserves in costly counter-attacks. Goodwood was preceded by the Second Battle of the Odon, preliminary attacks intended to inflict casualties and keep German attention on the east end of the bridgehead. On 18 July, I Corps conducted an advance to secure villages and the eastern flank of VIII Corps. On the western flank of VIII Corps, the II Canadian Corps conducted Operation Atlantic to capture the remaining German-held sections of the city of Caen south of the Orne River.

The Germans were able to contain the offensive, holding many of their rear defences on Bourguébus Ridge but had been shocked by the weight of the attack and preliminary aerial bombardment.[82] A defensive system less than 5 miles (8.0 km) deep could be overwhelmed at a stroke and the Germans had only the resources to hold ground in such depth in the sector south of Caen.[83] The south bank suburbs and industrial districts of Caen were captured by the Canadians, the British advanced 7 miles (11 km) east of Caen and ground for about 12,000 yards (11,000 m) to the south of Caen was taken.[84][85] The attack reinforced the German view that the Allied threat on the eastern flank was the most dangerous and more units were transferred eastwards, including the remaining mobile elements of the 2nd Panzer Division from the area south of Caumont. At the western end of the bridgehead, the US and Allied forces faced 1½ panzer divisions compared with 6½ facing the Allied forces on the eastern flank. Operation Cobra (25–31 July) broke through the defences of the Seventh Army west of St. Lô on 25 July, with few German armoured units in the area to counter-attack.[86]

Aftermath

Analysis

Shulman wrote that due to the attacks around the city of Caen, seven of the ten German panzer divisions in Normandy were facing the Anglo-Canadian forces, when the American forces launched Operation Cobra.[87] "What better justification for the strategy adopted by Allied planners to attract to the anvil of Caen the bulk of German armour and there methodically hammer it to bits!"[88] In 1962, British Official historian L. F. Ellis wrote that "Twenty-First Army Group's persistent pressure had compelled Rommel to make good a shortage of infantry by using his armour defensively. The strongest armoured divisions were clustered around that eastern flank until the American army had reached a position from which it was ready to break through the less heavily guarded western front."[89] Overy wrote that von Kluge warned Hitler that the German left flank had collapsed following Operation Cobra and "The choice was between holding at Caen and abandoning western France, or dividing German forces between two battles, and risking collapse in both." Hitler compromised by ordering the German army to hold in front of Caen, while armoured forces were diverted to tackle the American attack. "The result was predictable. Strong British and Canadian thrusts both sides of Caen immobilised the German forces and intercepted those driving towards the American front."[90] Ford called the battle for Caen a pyrrhic victory; the War Office had forecast that the 21st Army Group would have suffered 65,751 casualties by 7 August and actual casualties were 50,539 men.[91][92]

Damage and civilian casualties

Before the invasion, Caen had a population of 60,000 people. On 6 June, Allied aircraft dropped leaflets urging the population to leave but only a few hundred did so. Later in the day, British heavy bombers attacked the city to slow the flow of German reinforcements; 800 civilians were killed in the first 48 hours of the invasion. Streets were blocked by rubble, so the injured were taken to an emergency hospital set up in the Bon Sauveur convent. The Palais des Ducs, the church of Saint-Étienne and the railway station were all destroyed or severely damaged. About 15,000 people took refuge for more than a month in medieval quarry tunnels south of the city.[93]

The Défense Passive and other civil defence coordinated medical relief. Six surgical teams were alerted on the morning of the invasion and police brought medical supplies to Bon Sauveur and hospitals at Lycée Malherbe and Hospice des Petites Sœurs des Pauvres.[94] Many buildings caught fire and molten lead dripped from their roofs. About 3,000 people took refuge in Bon Sauveur, Abbaye aux Hommes and Saint Etienne church. Foraging parties were set out into the countryside for food, and old wells were re-opened. On 9 June, the bell tower of Saint Pierre was destroyed by a shell from the battleship Rodney. The Vichy government in Paris managed to get some supplies through to Caen under the auspices of Secours Nationale, 250 short tons (230 t) in total.[95]

The Germans ordered all remaining civilians to leave on 6 July; by the bombing during the evening of 7 July, only 15,000 inhabitants remained. 467 heavy bombers prepared the way for Operation Charnwood. Although the delayed-action bombs were aimed at the northern edge of Caen, massive damage was again inflicted on the city centre. At least two civilian shelters were hit and the University of Caen was destroyed, 350 people being killed by the raid and the fighting in Caen on 8 July, bringing the civilian death toll to 1,150 since D-Day.[96] The Germans withdrew from Caen north of the Orne on 9 July and blew the last bridge.[97] The southern part of the city was liberated on 18 July by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division.[98]

By the end of the battle, the civilian population of Caen had fallen from 60,000 to 17,000. Caen and many of the surrounding towns and villages were mostly destroyed; the University of Caen (founded in 1432) was razed. The buildings were eventually rebuilt after the war, and the University of Caen adopted the phoenix as its symbol. About 35,000 residents were made homeless after the Allied bombing and the destruction of the city caused much resentment.[99] After the war, the West German government paid reparations to the families of civilians killed, starved or left homeless by Allied bombing and fighting in Caen. The rebuilding of Caen officially lasted from 1948 to 1962. On 6 June 2004, Gerhard Schröder became the first German chancellor to be invited to the anniversary celebration of the invasion.

Atrocities

One hundred and fifty-six Canadian prisoners-of-war were shot near Caen by the 12th SS Panzer Division in the days and weeks following D-Day.[100] Twenty Canadians were killed near Villons-les-Buissons, north-west of Caen in Ardenne Abbey. The abbey was captured at midnight on 8 July by the Regina Rifles. The soldiers were exhumed and buried in the Bény-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery. After the war, Kurt Meyer was convicted and sentenced to death on charges of inappropriate behaviour towards civilians and the execution of prisoners,[101] a sentence later commuted to life imprisonment. He was released after serving eight years.[102]

Commemoration

There are many monuments to the Battle for Caen and Operation Overlord. For example, on the road to Odon-bridge at Tourmauville, there is a memorial for the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division; or the monument on hill 112 for the 53rd (Welsh) Infantry Division, as well as one for the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division. Near Hill 112, a forest was planted in memory of those that fought there.

The landings at Normandy, the Battle for Caen and the Second World War are remembered today with many memorials; Caen hosts the Mémorial with a "peace museum" (Musée de la paix). The museum was built by the city of Caen on top of where the bunker of General Wilhelm Richter, the commander of the 716th Infantry Division, was located. On 6 June 1988 French President François Mitterrand and twelve ambassadors from countries that took part in the fighting in Normandy joined to open the museum. The museum is dedicated to pacifism and borders the Parc international pour la Libération de l'Europe, a garden in remembrance of the Allied participants in the invasion.

The fallen are buried in the Brouay War Cemetery (377 graves), the Banneville-la-Campagne War Cemetery (2,170 graves), the Bény-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery (2,049 graves), the Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery (2,957 graves), La Cambe German war cemetery (21,222 graves) as well as many more.

See also

Media

Films

- D-Day 6.6.44 BBC documents advances on Caen

- based on Eisenhower: Crusade in Europe (1949)

- The Norman Summer (1962) CBS documentary

- In Desperate Battle: Normandy 1944 (1992) Canadian TV movie

- Road to Ortona (1962) Canadian documentary

- Turn of the Tide (1962) Canadian documentary

- V Was for Victory (1962) Canadian documentary

- Crisis on the Hill (1962) Canadian documentary

Games

- Call of Duty 2: Video game from the US game developer Infinity Ward. Released on 3 November 2005, the player is British Sergeant John Davis in the attack on Caen.

- Hidden & Dangerous 2: The player is a British SAS soldier that must liberate a town near Caen from the Germans.

- Battlefield 1942: This extremely popular multi-player game features a map of Caen only available with the latest patch which can be found on the Battlefield 1942 website. The two opposing teams, the Germans and the Canadians, must fight over the city of Caen.

- Company of Heroes: Opposing Fronts: The entire British campaign, spanning nine missions, is about the British Second Army's advance towards Caen and the battle of Caen.

- Day of Defeat a multiplayer Second World War first-person shooter computer video game features a map titled Caen which is based on the battle.

Notes

Citations

- 1 2 Trew, p. 22

- ↑ Forty, p. 36

- 1 2 Buckley (2004), p. 23

- 1 2 Taylor, p. 9

- ↑ Stacey, p. 142

- 1 2 Ellis, p. 247

- ↑ Gill, p. 24

- ↑ Clay, p. 254 and 256

- ↑ Forty, p. 37

- ↑ Ellis, p. 250

- ↑ Weigley, pp. 109–110

- ↑ Hart, p. 134

- ↑ Buckley24

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 308

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 16–78

- ↑ Forty, p. 160

- 1 2 Ellis, p. 255

- ↑ Fortin, p. 69

- ↑ Williams, p. 114

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 February 2014. Retrieved 2014-05-22.

- 1 2 3 "VICTORY CAMPAIGN, Failure at Les Mesnil-Patry: 11 June 44". warchronicle.com. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- 1 2 Martin & Whitsed 2008, p. 20.

- ↑ Stacey, p. 140

- 1 2 Ellis, p. 275

- ↑ Meyer, p. 340

- ↑ Saunders, p. 35

- ↑ Saunders, pp. 35–36

- ↑ Meyer, p. 386; Clark, pp. 42, 65

- 1 2 Baverstock, pp. 40–47

- ↑ Saunders, p. 123

- ↑ Ellis, p. 283

- ↑ Baverstock, pp. 65–149

- ↑ Williams, p. 114

- ↑ Clark, p. 22

- ↑ Clark, pp. 31–32

- ↑ Jackson, pp. 12, 22, 27

- ↑ Jackson, pp. 30–32

- ↑ Clark, p. 29

- ↑ Ellis, p. 277

- 1 2 Clark, p. 21

- ↑ Stacey, p. 150

- ↑ Jackson, p. 57

- ↑ Hart, p. 108

- ↑ Clark, p. 100

- ↑ Clark, p. 104; Copp, p. 18; Daglish, pp. 218–219; Gill, p. 30; Jackson, pp. 59, 114; Wilmot, p. 348

- ↑ Jackson, pp. 37, 40, 44, 53, 55 & 59

- ↑ Clark, pp. 107–109

- ↑ Jackson, p. 59

- ↑ Reynolds,p. 146

- ↑ Copp 2004, pp. 98, 111–112.

- ↑ Copp 2004, pp. 98, 113–115.

- ↑ Trew, p. 38

- ↑ Stacey, p. 157

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 351

- 1 2 Keegan, pp. 82–188

- ↑ Buckley, p. 31

- ↑ Trew, pp. 34, 36–37

- ↑ Ellis, p. 313

- 1 2 Trew, p. 37

- ↑ Scarfe, p. 70

- ↑ Keegan, p. 189

- 1 2 Cawthorne, p. 120

- ↑ Trew, p. 36

- ↑ D'Este, p. 313

- ↑ Copp (2004), p. 103

- ↑ Copp, p. 105

- ↑ Wood, p. 92

- 1 2 British Ministry of Defence

- ↑ Van der Vat, p. 150

- ↑ D'Este, p. 318

- ↑ Ellis, p. 316

- ↑ Jackson, p. 62

- ↑ Jackson, pp. 61–62

- ↑ Jackson, p. 62 et al.

- ↑ Bercuson, Pg. 222

- ↑ Copp, Fifth Brigade at Verrières Ridge, Pg. 2

- 1 2 Bercuson, Pg. 223

- ↑ Erik Hillis ([email protected]). "Canada at War". wwii.ca. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- 1 2 Scislowski

- ↑ Bercuson, Pg. 224

- ↑ Tank Tactics, Jarymowycz p. 132

- ↑ Ellis 1962, p. 352.

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 264

- ↑ Williams 2004, p. 131.

- ↑ Trew, p. 94

- ↑ Williams, p. 185

- ↑ Shulman, pp. 162–163

- ↑ Shulman, p. 166

- ↑ Ellis, p. 492

- ↑ Overy, p. 212

- ↑ Ford, p. 9

- ↑ Hart, p. 47

- ↑ Beevor, pp. 144–147

- ↑ Beevor, p. 146

- ↑ Beevor, pp. 200–202

- ↑ Beevor, pp. 266–269

- ↑ Beevor, p. 272

- ↑ Beevor, p. 315

- ↑ Beevor, p. 147

- ↑ Margolian, p. x (preface)

- ↑ Meyer, pp. 357, 372

- ↑ Meyer, p. 379

References

- Beevor, Antony (2009). D-Day: The Battle for Normandy. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-88703-3.

- Buckley, John (2006) [2004]. British Armour in the Normandy Campaign 1944. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-40773-7. OCLC 154699922.

- Cawthorne, Nigel (2005). Victory in World War II. London: Capella (Acturus). ISBN 1-84193-351-1. OCLC 222830404.

- Clark, Lloyd (2004). Operation Epsom. Battle Zone Normandy. The History Press. ISBN 0-7509-3008-X.

- Clay, Major Ewart W. (1950). The path of the 50th: The Story of the 50th (Northumbrian) Division in the Second World War. Aldershot: Gale and Polden. OCLC 12049041.

- Copp, Terry (2004) [2003]. Fields of Fire: The Canadians in Normandy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3780-1. OCLC 56329119.

- Daglish, Ian (2005). Operation Goodwood. Over the Battlefield. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 1-84415-153-0. OCLC 68762230.

- D'Este, Carlo (2004) [1983]. Decision in Normandy: The Real Story of Montgomery and the Allied Campaign. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-101761-9. OCLC 44772546.

- Ellis, Major L. F. (2004) [1962]. Victory in the West: The Battle of Normandy. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. I (N & M Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 1-845740-58-0.

- Ford, Ken; Howard, Gerrard (2004). Caen 1944: Montgomery's Breakout Attempt. Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-625-9.

- Fortin, Ludovic (2004). British Tanks In Normandy. Histoire & Collections. ISBN 2-915239-33-9.

- Forty, George (2004). Villers Bocage. Battle Zone Normandy. Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-3012-8.

- Gill, Ronald; Groves, John (2006) [1946]. Club Route in Europe: The History of 30 Corps from D-Day to May 1945. MLRS Books. ISBN 978-1-905696-24-6.

- Hart, Stephen Ashley (2007) [2000]. Colossal Cracks: Montgomery's 21st Army Group in Northwest Europe, 1944–45. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-3383-1. OCLC 70698935.

- Hastings, Max (2006) [1985]. Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy. New York: Vintage Books USA; Reprint edition. ISBN 0-307-27571-X. OCLC 62785673.

- Jackson, G. S.; Staff, 8 Corps (2006) [1945]. 8 Corps: Normandy to the Baltic. Smalldale: MLRS Books. ISBN 978-1-905696-25-3.

- Jarymowycz, R. (2001). Tank Tactics, from Normandy to Lorraine. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner. ISBN 1-55587-950-0.

- Keegan, John (2004) [1982]. Six Armies in Normandy: From D-Day to the Liberation at Paris. London: Pimlico. ISBN 1-84413-739-2. OCLC 56462089.

- Margolian, Howard (1998). Conduct Unbecoming: The Story of the Murder of Canadian Prisoners of War in Normandy. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8360-9.

- Martin, C. C.; Whitsed, R. (2008). Battle Diary: From D-Day and Normandy to the Zuider Zee and VE. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 1-55488-092-0.

- Meyer, Kurt (2005) [1957]. Grenadiers: The Story of Waffen SS General Kurt "Panzer" Meyer. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, US; New Ed edition. ISBN 0-8117-3197-9.

- Overy, Richard (1996). Why the Allies Won: Explaining Victory in World War II. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-7453-9.

- Reid, Brian (2005). No Holding Back. Robin Brass Studio. ISBN 1-896941-40-0.

- Reynolds, Michael (2001) [1997]. Steel Inferno: I SS Panzer Corps in Normandy. Da Capo Press. ISBN 1-885119-44-5.

- Scarfe, Norman (2006) [1947]. Assault Division: A History of the 3rd Division from the Invasion of Normandy to the Surrender of Germany. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Spellmount. ISBN 1-86227-338-3.

- Shulman, Milton (2004) [1947]. Defeat in the West. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-36603-X.

- Stacey, Colonel Charles Perry; Bond, Major C. C. J. (1960). The Victory Campaign: The Operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. III. Ottawa: The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. OCLC 58964926. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- Tamelander, Michael; Zetterling, Niklas (2004). Avgörandets Ögonblick: Invasionen i Normandie 1944. Norsteds Förlag. ISBN 978-91-7001-203-7. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- Taylor, Daniel (1999). Villers-Bocage Through the Lens. Old Harlow: Battle of Britain International. ISBN 1-870067-07-X. OCLC 43719285.

- Trew, Simon; Badsey, Stephen (2004). Battle for Caen. Battle Zone Normandy. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-3010-1. OCLC 56759608.

- Van der Vat, Dan (2003). D-Day; The Greatest Invasion, A People's History. Toronto: Madison Press. ISBN 1-55192-586-9. OCLC 51290297.

- Weigley, Russell F. (1981). Eisenhower's Lieutenants: The Campaigns of France and Germany, 1944–1945. Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-283-98801-0.

- Williams, Andrew (2004). D-Day to Berlin. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-83397-1. OCLC 60416729.

- Wilmot, Chester; Christopher Daniel McDevitt (1997) [1952]. The Struggle For Europe. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1-85326-677-9. OCLC 39697844.

- Wood, James A. (2007). Army of the West: The Weekly Reports of German Army Group B from Normandy to the West Wall. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-3404-8. OCLC 126229849.

Further reading

- Pogue, F. C. (1950). "D-Day to the Breakout". The Supreme Command. United States Army in World War II The European Theater of Operations. Washington: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army. OCLC 252766501.

- Steiger, A. G. (1952). Invasion and Battle of Normandy, 6 June – 22 August 1944 (PDF). The Campaign in North-West Europe: Information from German Sources. II. Ottawa: Canadian Army, Army Historical Section. OCLC 32228446. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- "The Drive on Caen: Northern France, 7 June – 9 July 1944" (PDF). Commemorative Booklets. London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- "The Final Battle for Normandy: Northern France, 9 July – 30 August 1944" (PDF). Commemorative Booklets. London: Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle for Caen. |

- 9th Canadian Brigade operations, 7 June 1944 (2012)

- The Battle of Caen, 1944

- Overview of the Battle for Caen

- Operation Charnwood

- Caen: Stalingrad of the Hitler Youth

- onWar.com Maps

- Caen Memorial

- Normandy field trip survival guide

- Légion Magazine Reassessing Operation Totalize

- Info about the massacre

- Info about the battle

- ornebridgehead.org

- junobeach.org

- Abbaye d'Ardenne

- Prison massacre 6 June 1944, Caen

Coordinates: 49°11′10″N 0°21′45″W / 49.18611°N 0.36250°W