Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River

Coordinates: 39°42′N 125°53′E / 39.700°N 125.883°E

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

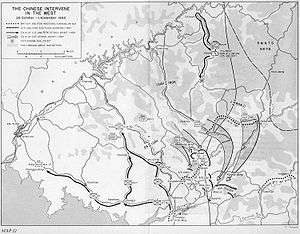

The Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River, also known as the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on(Chinese: 清川江战役) or the Second Phase Campaign Western Sector[nb 3] (Chinese: 第二次战役西线; pinyin: Dì Èr Cì Zhàn Yì Xī Xiàn), was a decisive battle in the Korean War, and it took place from November 25 to December 2, 1950, along the Ch'ongch'on River Valley in the northwestern part of North Korea. In response to the successful Chinese First Phase Campaign against the United Nations forces, General Douglas MacArthur launched the Home-by-Christmas Offensive to evict the Chinese forces from Korea and to end the war. Anticipating this reaction, the Chinese People's Volunteer Army Commander Peng Dehuai planned a counteroffensive, dubbed the "Second Phase Campaign", against the advancing UN forces.

Hoping to repeat the success of the earlier First Phase Campaign, the Chinese 13th Army[nb 4] first launched a series of surprise attacks along the Ch'ongch'on River Valley on the night of November 25, 1950, effectively destroying the Eighth United States Army's right flank while allowing Chinese forces to move rapidly into UN rear areas. In the subsequent battles and withdrawals during the period of November 26 to December 2, 1950, although the US Eighth Army managed to avoid being surrounded by Chinese forces, the Chinese 13th Army were still able to inflict heavy losses onto the retreating UN forces which had lost all cohesion. In the aftermath of the battle, the US Eighth Army's heavy losses forced all UN forces to evacuate North Korea and to withdraw to the 38th parallel.

Background

Well, if they go fast enough, maybe some of them can be home by Christmas.— General Douglas MacArthur[12]

In the wake of the United Nations (UN) forces' successful landing at Inchon and the subsequent destruction of the Korean People's Army (KPA) by mid-1950, the Eighth United States Army crossed the 38th parallel and advanced rapidly towards the Sino-Korean border.[13] Alarmed by this development, China's Chairman Mao Zedong ordered the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) to intervene in Korea and to launch the First Phase Campaign against the UN forces.[14] Between October 25 and November 4, 1950, the PVA 13th Army surprised and defeated the Republic of Korea (ROK) II Corps and the US 1st Cavalry Division in a series of battles around Onjong and Unsan, destroying the right flank of the US Eighth Army while forcing the UN forces to retreat back to the Ch'ongch'on River.[15] Although Chinese forces were able to break through the UN line, logistics difficulties forced the Chinese to withdraw on November 5, 1950.[16]

Despite the success of the Chinese First Phase Campaign, the UN planners still believed that China had not intervened in Korea on a large scale.[17] The suddenness of the Chinese withdrawal in the face of a victory further reinforced this belief.[18] Working on the assumption that only 30,000 Chinese troops could remain hidden in the hills,[19] General Douglas MacArthur ordered the bombing of the bridges over the Yalu River in an effort to cut off Chinese reinforcements.[20] Confident that the UN air force could detect and disrupt any troop movements across the Yalu River, MacArthur launched the Home-by-Christmas Offensive on November 24 to rout the remaining Chinese and North Korean forces and to end the Korean War.[21]

Unknown to the UN planners, however, there were already 180,000 Chinese troops stationed in Korea, with more reinforcements infiltrating across the border.[22] Although the PVA was ordered to maintain a defensive posture in North Korea until Soviet weapons could arrive in the spring of 1951,[23] its earlier successes convinced the Chinese leadership that the PVA was capable of turning the tide of UN advance.[24] Encouraged by the fact that the UN did not know their true numbers, PVA Commander Peng Dehuai outlined the Second Phase Campaign, a counteroffensive aimed at pushing the UN forces back to a line halfway between Ch'ongch'on River and Pyongyang.[5] As a part of a deception plan to further reinforce the weak appearance of Chinese forces, Peng ordered all units to rapidly retreat north while releasing POWs along the way.[25] With 230,000 troops at his disposal and another 150,000 heading to the Chosin Reservoir,[5] Peng authorized the start of the Second Phase Campaign on November 22, 1950.[26]

Prelude

Location, terrain and weather

The battle was fought along the UN front line around the Ch'ongch'on River and its tributaries,[27] which is located 50 mi (80 km) south of the Sino-Korean border.[28] The UN front line stretched horizontally from the Korean west coast to the Taebaek Mountains in central Korea,[29] while the Ch'ongch'on River crosses into the north of the UN line at the town of Kujang-dong.[30] From west to east, a series of towns, such as Chongju, Yongsan-dong, Ipsok, Kujang-dong, Tokchon, and Yongwon dot the front line,[31] and connecting those towns are a series of road junctions located at Sinanju, Anju, Kunu-ri and Pukchang-ni.[32] A road runs south from Kunu-ri into Sunchon and eventually into Pyongyang, and it would later become the main retreat route for the UN forces stationed at the center of the front line.[33] The hilly terrains on the northern bank of the Ch'ongch'on River formed a defensive barrier that allowed the Chinese to hide their presence while dispersing the advancing UN forces.[34] The battle was also fought over one of the coldest Korean winters in 100 years,[35] with temperatures dropped to as low as −30 °F (−34 °C).[36]

Forces and strategies

Acting on MacArthur's instructions, General Walton Walker of the Eighth Army started the Home-by-Christmas Offensive at 10 a.m. on November 24, 1950.[37] With a reconstituted ROK II Corps placed on the Eighth Army's right flank, the advance was led by the US I Corps to the west, US IX Corps in the center, and the ROK II Corps to the east.[38] The three UN Corps advanced cautiously in a continuous front line in order to prevent more ambushes similar to the Chinese First Phase Campaign,[38] but the lack of manpower stretched the UN forces to the limit.[38] Except for the strong Chinese resistances against the ROK II Corps, the Eighth Army met little opposition, and the line between Chongju to Yongwon was occupied on the night of the November 25.[39]

Despite the lack of manpower, the US Eighth Army had three and half times the firepower of the opposing Chinese forces.[40] The US Fifth Air Force, which was responsible for the air support, also had little opposition due to the lack of anti-aircraft weapons by the Chinese.[41] Boosted by a Thanksgiving feast with roasted turkeys on the eve of the advance, the morale was high among the UN ranks, and home by Christmas and Germany by spring was in everyone's mind.[42] The high morale, however, caused a degradation of troop discipline, and most of the soldiers had discarded their equipment and ammunition supply before the battle. A rifle company from the US IX Corps, for example, started its advance with most of the helmets and bayonets thrown away, and there were on average less than one grenade and 50 rounds of ammunition carried per man.[43] Because the UN planners did not foresee that the war would be dragged into a winter campaign, all elements of the Eighth Army started the offensive with a shortage of winter clothing.[37]

| "As a main objective, one of the units must fight its way rapidly around the enemy and cut off their rear.... Route of attack must avoid highways and flat terrain in order to keep tanks and artillery from hindering the attack operations.... Night warfare in mountainous terrain must have a definite plan and liaison between platoon commands. Small leading patrol groups attack and then sound the bugle. A large number will at that time follow in column." |

| Chinese operation principles for the Second Phase Campaign[44][45] |

While the Eighth Army was advancing, the PVA 13th Army was hiding in the mountains with the 50th and 66th Corps to the west, the 39th and the 40th Corps in the center and the 38th and 42nd Corps to the east.[6] Anticipating the UN advances, the Chinese planned a series of counterattacks to catch the Eighth Army off guard.[5] Hoping to repeat the success of the earlier First Phase Campaign, the 38th and 42nd Corps would first attack the ROK II Corps and to destroy the UN right flank, then cut behind the UN lines.[46] At the same time, the 39th and 40th Corps would hold the US IX Corps in place while preventing any reinforcements to the ROK II Corps.[47] The 50th and 66th Corps would stay behind and check the advances of the US I Corps.[47]

Although the PVA 13th Army had a nominal strength of 230,000 men,[6] its actual strength during the battle could be as low as 150,000 men.[27] The PVA 66th Corps, for example, had only 6,600 men per division at the start of the battle,[48] as opposed to the expected 10,000 men per division.[49] There were also only one firearm available for every three Chinese soldiers, and the rest were employed as grenade throwers.[41] Because most of the Chinese howitzers and guns were left behind in Manchuria, mortars were the only artillery support available for the Chinese.[41] For the counteroffensive, the average Chinese soldier were issued with only five days worth of rations and ammunition, and resupply could only be obtained by scavenging on the battlefield.[50] To compensate for its shortcomings, the Chinese relied extensively on night attacks and infiltrations in order to avoid the UN firepower.[51] The primitive logistics system had also allowed the Chinese to maneuver over the rough hilly terrains, thus enabled them to by-pass the UN defenses and to surround the isolated UN positions.[52][53] Because the Chinese had captured large numbers of Nationalist weapons during the Chinese Civil War, most of the Chinese weapons were composed of US made small arms such as the Thompson submachine gun, the M1 Garand rifle, the M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle, the bazooka and the M2 mortar.[54]

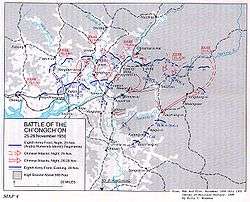

Battle

As the US Eighth Army stopped its advance on the afternoon of November 25, 1950, the PVA 13th Army commenced the Second Phase Campaign.[55] A massive frontal attack was launched against the entire UN line from Yongsan-dong to Yongwon.[56] To the west, the ROK 1st Infantry Division of the US I Corps was attacked by the PVA 66th Corps at Yongsan-dong. In the center, strong probing actions by the PVA 39th and 40th Corps were carried out against the US IX Corps at Ipsok and Kujang-dong. In the east, the PVA 38th and 42nd Corps broke through ROK II Corps' line at Tokchon and Yongwon. The Home-by-Christmas Offensive was completely stalled on the morning of November 26.[57]

Actions at Tokchon and Yongwon

In the aftermath of the Battle of Onjong, the Chinese recognized the ROK II Corps as the most vulnerable unit of the Eighth Army.[46] Besides lacking the firepower of their US counterpart,[40] the ROK II Corps also held the most difficult terrain on the UN right flank.[46] At 10 a.m. on November 24, the ROK 7th Infantry Division on the II Corps' left flank attacked north from Tokchon.[58] At the same time, the ROK 8th Infantry Division on the II Corps' right flank advanced north from Yongwon.[59] The stubborn defenses by the PVA 38th and 42nd Corps soon ground the Korean advances to a halt, and the continuous fighting for the next two days failed to create any gains for the Koreans.[60] During the advances, the Chinese defenses managed to create a wedge in the center of the ROK 7th Infantry Division, forcing the division to commit most of its reserves on the front line.[61] Meanwhile, the ROK 6th Infantry Division in the II Corps' rear could only offer its 2nd Infantry Regiment as the corps' reserve due to the earlier losses at Onjong.[62]

As the Koreans were preparing their defensive positions on the dusk of November 25, the two Chinese corps were mobilizing for a decisive counterattack against the Eighth Army's right flank.[55] The PVA 38th Corps planned to attack in full force against the ROK 7th Infantry Division's center and right flank, while two divisions from the 42nd Corps started to march through the hills in order to bypass the ROK 8th Infantry Division's right flank.[63] Given the importance of this assault, Han Xianchu, one of Peng's deputies, personally commanded the 38th and 42nd Corps for the rest of the battle.[64]

The PVA 38th Corps landed the first blow against the ROK II Corps at 5 p.m. on November 25.[65] Aided by total surprise, the PVA 113th Division of the 38th Corps first shattered the ROK 7th Infantry Division's Reconnaissance Company on the division's right flank,[66][67] creating a 0.5 mi (800 m) gap between the ROK 7th and 8th Infantry Division.[65] Simultaneously, the PVA 114th Division of the 38th Corps attacked the center-right of the ROK 7th Infantry Division, pushing the ROK 5th and 8th Infantry Regiment back in the process.[67][68] When the ROK 7th Infantry Division's center and right were in complete chaos, the PVA 112th and the 113th Division of the 38th Corps slipped past the UN lines and advanced towards Tokchon.[64] With only one battalion in reserve to check the Chinese divisions, the Tokchon garrison and the ROK 7th Infantry Division headquarters were soon surrounded and attacked by the two Chinese divisions at 4 a.m. on November 26.[64][69] Under heavy pressures from the PVA 114th Division, the ROK 5th and 8th Infantry Regiment tried to fall back to Tokchon, but the Chinese ambushes in the rear scattered the unsuspecting Koreans.[69] On the afternoon of November 26, Tokchon was captured by the Chinese,[70] and the ROK 3rd Infantry Regiment on the ROK 7th Infantry Division's left flank drifted westward and joined the US 2nd Infantry Division.[59]

While the ROK 7th Infantry Division was being annihilated at Tokchon by the PVA 38th Corps, the ROK 8th Infantry Division was also being routed, at Yongwon by the PVA 42nd Corps. With the PVA 125th Division tying down the ROK 10th and 21st Infantry Regiment at Yongwon,[71] the 124th and the 126th Division tried to infiltrate the ROK 8th Infantry Division's rear by marching through the hills east of Yongwon.[72] At 1 p.m. on November 25, the ROK 16th Infantry Regiment to the ROK 8th Infantry Division's rear spotted the two Chinese divisions at Maengsan, 20 km (12 mi) south of the Yongwon.[71] Surprised by this development, the ROK 8th Infantry Division ordered the 16th Infantry Regiment to block the Chinese advance while the ROK 10th and 21st Infantry Regiment were retreating from Yongwon.[73] But before the order could be carried out, the Chinese struck first after learning their trap had been discovered.[72] As the ROK 10th and 21st Infantry Regiment were retreating from Yongwon early in the morning of November 26, the PVA 125th Division ambushed both ROK regiments, forcing the Koreans to abandon their heavy equipment and to scatter into the hills.[74] Meanwhile, following the bonfires made by the Koreans for the cold weather,[75] the PVA 124th Division overran a battalion from the ROK 16th Infantry Regiment and attacked the ROK 8th Infantry Division's command post at Maengsan.[76] With the entire division dispersed, the ROK 8th Infantry Division headquarters and the ROK 16th Infantry Regiment broke out of Maengsan on November 27 and retreated from the battlefield.[77]

During the chaos of the battle, Major General Yu Jai Hung of the ROK II Corps did not receive news from the front line until midnight of November 25 — five hours after the Chinese had entered the Korean rear.[78] Responding to the crisis, Hung committed the ROK 2nd Infantry Regiment of the 6th Infantry Division to block the Chinese divisions.[66] As the 2nd Infantry Regiment marched towards the front on the morning of November 26, the PVA 113th Division intercepted the regiment and destroyed its command post, scattering the ROK II Corps' entire reserve in the process.[67][79] With most the ROK II Corps' units destroyed by November 27, the UN right flank had fallen to the Chinese.[80]

Although the UN aerial reconnaissance observed on November 27 that the Chinese forces on the UN right flank were moving rapidly into the Eighth Army's rear,[81] Walker still ordered the rest of the Eighth Army to continue the offensive north.[75][82] Convinced that the collapse of the ROK II Corps was merely a small counterattack by the Chinese,[75] Walker ordered the US I and IX Corps to shift eastward in order to cover the ROK II Corps' sector.[83] By that time, however, the US I and IX Corps had already suffered heavy losses from the Chinese counteroffensive at Kujang-dong, Ipsok and Yongsan-dong.

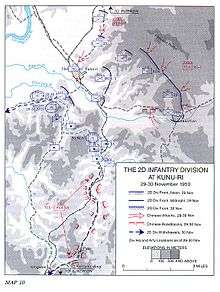

Actions at Kujang-dong

On the left of the ROK 7th Infantry Division, ROK II Corps, the US 2nd Infantry Division of the IX Corps was placed in the path of a major Chinese supply line.[84] During the Home-by-Christmas Offensive, US 9th Infantry Regiment led the division's advance northward along the Ch'ongch'on River, while the US 38th Infantry Regiment was placed on the division's right flank.[85] The offensive started with little resistance against the US 2nd Infantry Division, although the 9th Infantry Regiment was stalled by Chinese defenses at Hill 219, north of Kujang-dong on November 25.[84] In order to renew the offensive on the next day, the 23rd Infantry Regiment of the US 2nd Infantry Division was moved into the rear of the 9th Infantry Regiment.[84] At the same time, the 38th Infantry Regiment had arrived at Somin-dong, a town on the road between Kujang-dong and Tokchon.[86] When the aerial reconnaissance detected an increase in Chinese activities, the 38th Infantry Regiment's A Company was sent on a patrol into Chinese territory.[86]

To ensure the success of the Chinese counterattack against ROK II Corps, the PVA 40th Corps was assigned the mission of protecting the PVA 38th Corps' flank against the US 2nd Infantry Division.[72] To accomplish this mission, the PVA 119th Division of the 40th Corps would first attack Somin-dong and to prevent the Americans from reinforcing the Koreans.[87] The 120th Division would then fight its way across the Ch'ongch'on River and tie down the bulk of the US 2nd Infantry Division.[87] Finally, the 118th Division would flank the Americans from the west and capture Kujang-dong from the rear.[87]

On the night of the Chinese counteroffensive, the PVA 120th Division first accidentally stumbled upon the US 9th Infantry Regiment on the northern bank of the Ch'ongch'on River.[87][88] The surprise encounter between the two sides soon left the 9th Infantry Regiment with only three rifle companies combat effective.[89] Unaware that the 1st Battalion of the US 23rd Infantry Regiment had pulled up behind the US 61st Field Artillery Battalion,[90] four Sharp Sword Companies from the PVA 359th Regiment of the 120th Division proceeded to cross the river and attacked the US artillery positions.[87] Although the 61st Battalion was routed by surprise,[90] the US 23rd Infantry Regiment quickly knocked out two of the unsuspecting Chinese companies.[87][91] The surviving Chinese troops drifted eastward and occupied a hill named Chinaman's Hat,[87] enabling the Chinese to overlook the entire 23rd Infantry Regiment's positions.[92]

While the PVA 120th Division commenced its attack on the US 2nd Infantry Division's center, the PVA 119th Division was also trying to drive a wedge between Kujang-dong and Tokchon.[87] In a series of confusing battles between the PVA 119th Division and the US 38th Infantry Regiment, the patrolling A Company of the 38th Infantry Regiment was first splintered under Chinese attacks.[93] Adding to the confusion, Chinese reconnaissance teams resorted to sweet musics and dancing to lure the Americans into exposing their positions,[94] and the resulting Chinese counter fire caused the loss of the G Company on the 38th Infantry Regiment's center.[95] The Chinese had also penetrated the 38th Infantry Regiment's left flank, blocking the regiment's retreat route in the process.[96] By the morning of November 26, Chinese troops were spotted all around the 38th Infantry Regiment.[97]

The Chinese promptly withdrew as the morning came on November 26, and a counterattack by the 38th Infantry Regiment later reopened the road to the rear.[96] When the ROK 3rd Infantry Regiment of the ROK 7th Infantry Division suddenly appeared in the 38th Infantry Regiment's sector, Colonel George B. Peploe of the 38th Infantry Regiment realized the right flank of the US 2nd Infantry Division and the entire Eighth Army had collapsed.[98] Under orders from Major General Laurence B. Keiser, commander of the US 2nd Infantry Division, Colonel Peploe immediately took command of the ROK 3rd Infantry Regiment while trying to refuse his right flank.[98] At the same time, Colonel Paul L. Freeman of the 23rd Infantry Regiment had also tried to lead his regiment to capture Chinaman's Hat, but without much success.[99]

The Chinese immediately renewed their attacks on the night of November 26. A counterattack from Chinaman's Hat soon captured the 23rd Infantry Regiment's command post.[100] On the 23rd Infantry Regiment's left, the 9th Infantry Regiment's G Company was also overran by the attacking Chinese forces, forcing Colonel Charles C. Sloane Jr. to withdraw the remnants of his regiment across the river.[89] Chinese ambushes in the rear then decimated the rest of the 9th Infantry Regiment.[101] To the US 2nd Infantry Division's right, Commander Wen Yuchen of the PVA 40th Corps ordered the 119th Division to destroy the 38th Infantry Regiment in order to protect the Chinese breakthrough on the UN right flank.[102] The ferocious fighting soon forced the 38th Infantry Regiment to fight its way back to Kujang-dong in order to rejoin the division.[103]

Although Walker did not cancel the Home-by-Christmas Offensive on November 27, Keiser ordered his division to withdraw to Kujang-dong.[82] Before Keiser's order was complete on November 28, Walker instructed Major General John B. Coulter of the IX Corps to set up a new defensive line at Kunu-ri — 20 mi (32 km) south of the US 2nd Infantry Division.[104] Full scale retreat of the US 2nd Infantry Division started on the night of November 27, with the Chinese attacking everywhere against the Americans.[105] As the division's convoy tried to move south, they were met with machine gun and mortar fire from numerous Chinese roadblocks in the rear.[106] Chinese bazooka teams had also knocked out several vehicles while others were trying to swarm the tanks and to lob grenades into the hatch.[107] With some losses, the US 2nd Infantry Division broke through the PVA 118th Division's blockade and arrived at Kunu-ri on the night of November 28.[87][108]

Actions at Ipsok

For the Home-by-Christmas Offensive, US 25th Infantry Division of the IX Corps advanced on the left of the US 2nd Infantry Division along the Kuryong River, one of the northern tributaries of the Ch'ongch'on River.[109] On November 24, the 25th Infantry Division started its offensive at the city of Yongbyon, south of Ipsok.[110] To lead the offensive, five companies of infantry, armor and artillery were drawn from the 25th Infantry Division to form a special task force named "Task Force Dolvin".[111] With Task Force Dolvin leading the offensive on the eastern bank of the Kuryong River, the US 24th Infantry Regiment of the 25th Infantry Division was placed on division's right to maintain contact with the 2nd Division,[109] while the US 35th Infantry Regiment of the 25th Infantry Division was on the western bank of the river advancing from Yongsan-dong to Unsan.[112] The 27th Infantry Regiment of the 25th Infantry Division was located in the division's rear as reserves.[113]

Because of the earlier UN defeat at the Battle of Unsan, the US 25th Infantry Division expected to encounter heavy Chinese resistance during its advance.[109] But the Chinese screening forces withdrew with the American advance.[114] Aside from the harassing fire, the US 25th Infantry Division did not encounter strong resistance along the way.[115] Ipsok was captured by Task Force Dolvin on November 24, and several American POWs from the Unsan battle were also recovered at the town.[114] When Task Force Dolvin proceeded to capture a series of hills north of Ipsok on the next day,[116] Chinese resistance started to stiffen.[117] During the hill battles on the afternoon of November 25, the Eighth Army Ranger Company of Task Force Dolvin suffered heavy losses against the Chinese defenses,[118] and the task force stopped its advance at dusk.[117]

While the US 25th Infantry Division was advancing, the opposing PVA 39th Corps was waiting for instructions from the PVA High Command.[119] But the Chinese still conducted a series of probing actions against the American positions on the night of November 25. The Chinese patrols soon destroyed the rest of the Ranger Company,[120] while numerous Chinese reconnaissance teams disguised as Americans infiltrated Task Force Dolvin's positions.[121] On the right of Task Force Dolvin, the mountainous terrains scattered US 24th Infantry Regiment while blocking most of its radio transmissions.[122] Upon learning the destruction of the Ranger Company, Major General William B. Kean of the US 25th Infantry Division sent the 2nd Battalion of the 27th Infantry Regiment to reinforce Task Force Dolvin.[123] He also sent the assistant division commander Brigadier General Vennard Wilson to command of the task force, renaming the task force "Task Force Wilson".[124]

After the successful attack against the Eighth Army's right flank, the PVA High Command gave the go ahead for the 39th Corps to attack the US 25th Infantry Division on November 26.[119] The PVA 115th Division of the 39th Corps was immediately mobilized for an assault against Task Force Wilson and the US 24th Infantry Regiment, while the 116th and 117th Division were moving to attack Ipsok and to cut the American retreat route.[125] The crushing attack soon left the task force decimated and reeling.[126] The PVA 347th Regiment of the 115th Division first met the C Company on the task force's center,[125] and after the sharp encounter most of the C Company's men were missing in action.[127][nb 5] On the right flank, the 115th Division attacked the task force's B Company.[125] Met with waves of Chinese suicide bombers, the B Company was reduced to 26 soldiers out of the original 200.[127] Some Chinese snipers and infiltrators even managed to reach Task Force Wilson's command post, resulting in the death of the task force's executive officer.[128] As the entire task force's line collapsing, the E Company sleeping at the task force's rear was pushed to the front line.[127] Although the tank fire from the E Company stopped the Chinese advance,[129] the company was reduced to just one platoon after the battle.[130] Chinese forces in the rear had also attacked the task force's artillery at Ipsok, preventing fire support during the night.[131] In the aftermath of the night battle, the task force found itself surrounded, and the Chinese troops were chanting in all directions against the Americans.[132] When Wilson tried to evacuate the wounded, Chinese roadblocks ambushed the medical convoy just south of the 2nd Battalion's perimeter.[133]

With only the 2nd Battalion of Task Force Wilson remaining combat effective on the morning of November 27, Wilson ordered the task force to withdraw to Ipsok.[130] Under heavy air cover,[134] the 2nd Battalion broke through PVA 348th Regiment's roadblock and reached Iposk on the afternoon.[125][134] Meanwhile, the US 24th Infantry Regiment had lost contact with most of its units, and the regiment commander Colonel John T. Corley could only collect one battalion from his regiment on the morning of November 27.[113][nb 6] On November 28, Walker shifted the US I Corps eastward by attaching the US 25th Infantry Division to the US I Corps, while ordering the 25th Infantry Division to withdraw to the Ch'ongch'on River.[83][135] With the US 35th Infantry Regiment rejoining the 25th Infantry Division after the battle at Yongsan-dong,[136] the 25th Infantry Division withdrew south and Task Force Wilson was dissolved by Kean on November 28.[135]

Actions at Yongsan-dong

After an extensive refit in the aftermath of the Unsan battle, ROK 1st Infantry Division was placed on the US I Corps right flank at Yongsan-dong on November 20.[137] As part of the Home-by-Christmas Offensive, the ROK 1st Infantry Division was to advance north and to capture the town of Taechon[138] while the US 35th Infantry Regiment of the US 25th Infantry Division was advancing north from Yongsan-dong on the Korean right flank.[139] At the same time, the US 24th Infantry Division of the US I Corps would advance towards Chongju on the ROK 1st Infantry Division's left flank.[138]

On the morning of November 24, the ROK 1st Infantry Division advanced towards the town of Taechon with its 11th and 12th Infantry Regiment on point.[138] Although Chinese booby traps and mortar fire tried to delay the Koreans along the way, the 1st Infantry Division still managed to envelope the town by the dusk of November 24.[138] But unknown to the Koreans, the 1st Infantry Division was marching into a Chinese assembly area, and the resistance around Taechon immediately increased as the result.[140] On the night of November 24, the defending PVA 66th Corps counterattacked the Koreans with infantry and cavalry charges,[138][140] and the Chinese and Korean troops were soon locked in a seesaw battle from November 25 to 26.[140]

As the battle around Taechon dragged into the night of November 26, the ROK 11th Infantry Regiment on the division's right became disorganized.[140] Brigadier General Paik Sun Yup of the ROK 1st Infantry Division soon brought up the 15th Infantry Regiment from his reserve to relieve the 11th Infantry Regiment.[140] After receiving news on the Chinese attack against the 25th Division across the Kuryong River, Paik had also directed his division to defend against the upcoming Chinese counteroffensive.[138] As the morning came on November 27, the Chinese troops around Taechon did not stop their assault even under punishing UN air strikes, and some of the attacks spilled into US 24th Infantry Division's area.[141] Upon noticing their flank was buckling, the US 24th Infantry Division and the US 35th Infantry Regiment started the retreat southward to the Ch'ongch'on River.[142]

At 1 p.m. on November 27, Peng ordered the PVA 66th Corps to destroy the ROK 1st Infantry Division before the Koreans could retreat to the Ch'ongch'on River.[143] On the evening of November 27, the PVA 66th Corps launched a massive attack against the ROK 1st Infantry Division, the US 5th Regimental Combat Team of the 24th Infantry Division and the US 35th Infantry Regiment.[144] After midnight, the Chinese attacks broke through the Korean lines and captured Yongsan-dong, resulting in the loss of the ROK 11th, 15th and US 35th Infantry Regiment's command posts.[145] The ROK 11th and 15th Infantry Regiment were soon scattered[146] while the retreating US 35th Infantry Regiment was blocked at Yongsan-dong with Chinese forces attacking from behind.[147] Under heavy pressure, the US 35th Infantry Regiment fought its way through the town and rejoined the US 25th Division on the afternoon of November 28.[147] At the same time, Paik rallied the broken ROK regiments and recaptured Yongsan-dong.[146] The ROK 1st Infantry Division held the town against the subsequent Chinese attacks until it withdrew from the battle on November 29.[148]

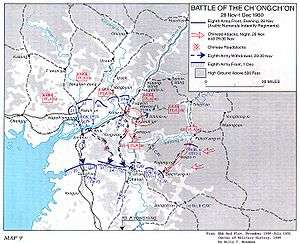

Actions at Kunu-ri

Kunu-ri is a crossroad village on the northern bank of the Kaechon River, one of Ch'ongch'on River's southern tributaries.[33] As the Chinese counteroffensive grew in strength against the Eighth Army's center, Kunu-ri had become a major bottleneck for the US IX Corps' retreat.[33] In an effort to stabilize the front on November 28, Walker ordered the US 2nd Infantry Division to retreat from Kujang-dong and to set up a new defensive line at Kunu-ri.[149] The importance of Kunu-ri was also noted by the Chinese, and on November 27, Peng instructed the PVA 38th Corps to cut the US IX Corps retreat route.[143] The PVA 114th Division of the 38th Corps would capture Kunu-ri by marching westward on the road from Tokchon, while the PVA 112th Division would follow on a parallel route through the hills north of the road.[150]

With the US 2nd Infantry Division still at engaged at Kujang-dong, Coulter ordered the Turkish Brigade in the IX Corps reserve to block the Chinese advance.[151] On the night of November 27, the Turks took up defensive position at Wawon to the east of Kunu-ri.[152] They were soon met with the PVA 342nd Regiment from the 114th Division.[150] The ensuing battle between the Chinese regiment and the brigade's advance battalion continued for much of the November 28, resulting 400 Turkish casualties.[153][154] As dusk came on November 28, the Turkish Brigade tried to retreat 5 km (3.1 mi) west to Sinim-ri to set up stronger defensive positions, but the PVA 342nd Regiment caught up with the brigade and attacked its rear, completely surrounding the brigade.[153][155] With communications cut between the brigade and the Turkish headquarters,[153] the PVA 340th and the 342nd Regiment from the 114th Division then fragmented the brigade during the night battle.[155][156] The trapped Turks broke out of the Chinese encirclement on the morning of November 29 and the brigade was attached to the US 2nd Infantry Division.[157]

Although the Turkish Brigade was crippled by the Chinese, its delaying action allowed the US 2nd Infantry Division to secure Kunu-ri on the night of November 28.[158] With the US 23rd Infantry Regiment setting up defensive positions to the north of Kunu-ri on the morning of November 29, the US 38th Infantry Regiment tried to occupy the hills to the northeast of Kunu-ri.[159] But the American soon found the PVA 112th Division had already occupied the hills.[159][160] The 38th Infantry Regiment was then forced to occupy a lower position at 1 mi (1.6 km) away from the Chinese.[159] At the same time, the remnants of the Turkish Brigade joined up with the US 38th Infantry Regiment, covering the regiment's right flank on the northern bank of the Kaechon River.[161]

On the afternoon of November 28, MacArthur started to recognize that a crisis was growing in Korea.[162] With the start of the Battle of Chosin Reservoir on November 27, MacArthur gathered his field commanders, including Walker, for a conference in Tokyo.[163] During the conference, MacArthur learned about the situation on the Eighth Army's right flank and judged that the Eighth Army was in great danger.[164] He instructed Walker to withdraw from the battle before the Chinese could surround the Eighth Army.[165] After the conference at November 29, Walker ordered all Eighth Army units to retreat to a new line around Sunchon, 30 mi (48 km) south of Kunu-ri.[34]

Following Walker's orders, most of the Eighth Army's major units promptly broke contact with the Chinese and withdrew,[166] but the US 2nd Infantry Division was forced to stay at Kunu-ri in order to hold off the Chinese forces on the Eighth Army's right flank.[167] By the time the 2nd Infantry Division tried to withdraw on the night of November 29, the two Chinese divisions attacked the US 38th Infantry Regiment. The PVA 112th Division first struck the 38th Infantry Regiment on the left flank,[168] but the American defenses held firm,[168] forcing the Chinese to go on the defensive.[160] Meanwhile, the PVA 114th Division attacked the Turkish Brigade and the right flank of the 38th Infantry Regiment.[155] The Chinese outflanked the Turks by attacking along the southern bank of the Kaechon River, then crossed the river in the UN rear areas.[169] Upon noticing this development, Brigadier General Tahsin Yazıcı of the Turkish Brigade ordered a withdrawal,[169] leaving the right flank of the 38th Infantry Regiment completely uncovered.[168] By the dusk of November 29, Chinese had cut the road between the 38th Infantry Regiment and Kunu-ri,[170] and the Americans had to retreat by infiltrating the Chinese lines.[171] At 4 a.m. on November 30, the 38th Infantry Regiment crossed the Kaechon River under the cover of the 23rd Infantry Regiment and Kunu-ri was under Chinese control.[172]

The Gauntlet

In the aftermath of the ROK II Corps' collapse on November 27, Peng immediately ordered the PVA 38th Corps to cut the road between Kunu-ri and Sunchon in the US IX Corps rear, while the PVA 42nd Corps would surround the entire Eighth Army by rushing south through Pukchang-ni and capture Sunchon.[143] At the same day, Walker shifted the Eighth Army's line eastward by attaching the US 1st Cavalry Division and the Anglo-Australian 27th Commonwealth Infantry Brigade to the US IX Corps.[83] The US 1st Cavalry Division would contain the Chinese breakthrough at Pukchang-ni,[173] while the 27th Commonwealth Brigade secured the road between Kunu-ri and Sunchon.[174]

With the new orders on November 28, the US 5th Cavalry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division left Kunu-ri to rejoin the division to the northeast of Sunchon.[75] With the US 5th Cavalry Regiment absent and the 8th Cavalry Regiment still recovering from the earlier losses from the battle at Unsan, Major General Hobart Gay of the US 1st Cavalry Division placed the US 7th Cavalry Regiment to the south of Pukchang-ni, behind the remnants of the ROK 6th Infantry Division.[175][176] Lacking reinforcements, the ROK 6th Infantry Division was quickly routed by the PVA 42nd Corps on the night of November 28.[155][177] Chinese forces then attacked the 7th Cavalry Regiment under the cover of the fleeing Korean soldiers and refugees pouring into the American front.[178] Under Gay's order, the 7th Cavalry Regiment withdrew southwest to the town of Sinchang-ni on the morning of November 29, and the Chinese resumed the drive southward.[179] A fierce battle between the PVA 125th Division and the 7th Cavalry Regiment broke out during the night of November 29, but by the morning of November 30 the PVA 42nd Corps' advance was halted.[180]

The PVA 38th Corps, on the other hand, was marching towards the Kunu-ri—Sunchon road virtually unopposed.[150] On 7 a.m. at November 28, the PVA 113th Division of the 38th Corps occupied the town of Samo-ri,[150] placing it right in the path of the 5th Cavalry Regiment and besides the Kunu-ri—Sunchon road.[181] An hour and half later, the advance platoon from the 5th Cavalry Regiment was ambushed and destroyed.[173] With its advance blocked, the 5th Cavalry Regiment tried to dislodge the Chinese garrison, but it was forced to turn back by the afternoon.[182] The 113th Division then occupied the valley containing the Kunu-ri—Sunchon road at that night and blocked the retreat route of the US 2nd Infantry Division.[33][155] Upon receiving the news on November 29, 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, part of 27th Brigade, tried to clear the valley from the south, but the attack was halted due to the lack of heavy weapons.[183]

One of the first victims of the new Chinese roadblock was a convoy from the Turkish Brigade, and it was ambushed on the night of November 28.[184] A military police patrol was sent to investigate, but most of its members were killed by the morning.[185] With the battle still raging at Kunu-ri, the news of the Chinese roadblock reached the US 2nd Infantry Division on November 29.[185] Keiser sent the Reconnaissance Company and the remnants of the 9th Infantry Regiment to dislodge the Chinese, but the roadblock held firm even with a platoon of tanks attacking it.[184] With the battle at Kunu-ri ended by the night of November 29, the PVA 112th Division joined the 113th Division[186] and the roadblock grew to 6 mi (9.7 km) in depth.[187]

| "For the next 500 yards the road was temporarily impassable because of the numerous burning vehicles and the pile up of the dead men, coupled with the rush of the wounded from the ditches, struggling to get aboard anything that rolled...either there would be bodies in our way, or we would almost borne down by wounded men who literally throw themselves upon us...I squeezed [a wounded ROK soldier] into our trailer. But as I put him aboard, other wounded men piled on the trailer in such number that the Jeep couldn't pull ahead. It was necessary to beat them off." |

| Lieutenant Colonel William Kelleher of the US 1st Battalion, 38th Infantry Regiment describing the carnage at the Gauntlet[188] |

The 2nd Infantry Division, however, did not know the strength of the roadblock on the night of November 29.[167] At the same time, the US 25th Infantry Division Military Police mistakenly reported that the alternative retreat route from Kunu-ri to Anju was also blocked by Chinese.[187] Later, Coulter ordered Keiser to withdraw by breaking the roadblock with the 27th Commonwealth Brigade.[189] On the early morning of November 30, Keiser made the decision to withdraw through the valley.[190]

On the morning of November 30, the 9th Infantry Regiment led the withdrawal by attacking the roadblock. Four tanks were first sent down the road and the Chinese held their fire.[191] Encouraged by this development, Colonel Sloane ordered the 9th Infantry Regiment to press forward, but Chinese machine gun and mortar fire immediately stopped the advance at 9 a.m.[191] The ROK 3rd Infantry Regiment attached to the 2nd Infantry Division was sent to reinforce the US 9th Infantry Regiment, but it was routed by friendly fire.[192][193] With no contacts between the American commands and the British units,[194] the Middlesex Regiment advanced to the south end of the valley without attacking the roadblock.[195] Believing that the roadblock was short and the British were attacking up the road,[196] Keiser ordered the 2nd Infantry Division to run through the blockade at 10 a.m.[197]

As the 2nd Infantry Division entered the valley, later known as the "Gauntlet",[1] the Chinese machine guns delivered punishing fire while mortar shells saturated the road.[198] The length of the roadblock caught the 2nd Infantry Division by surprise,[199] and the road was soon filled with wrecked vehicles and wounded and dead soldiers.[200] Those who tried to take cover in the ditches were promptly left behind by the convoy rushing south, and unit cohesion instantly evaporated.[199] During the day, the air cover tried to suppress the Chinese positions with some success, but with no air cover at night, the Chinese attack intensified.[199] Finally, the Chinese blocked the road completely by destroying the US 38th and 503rd Artillery Battalion of the 2nd Infantry Division,[201] and the immobilized artillery pieces forced the rest of the division to abandon all vehicles and to retreat by hiking through the hills.[199][201] At the rear of the division, Colonel Freeman attempted to save his 23rd Infantry Regiment by retreating through the Kunu-ri—Anju road.[202] In one of the last acts of the battle, the 23rd Infantry Regiment fired off its stock of 3,206 artillery shells within 20 minutes,[200] and the massive barrage shocked the Chinese troops from following the regiment.[203] The last stragglers from the US 2nd Infantry Division finally arrived at Sunchon on December 1, and by December 2 the Eighth Army had completely lost contact with the Chinese.[204]

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the battle, US Eighth Army's casualty number exceeded 11,000 in the first count.[9] A large number of documents, including all records from the US 2nd Infantry Division and the US 24th Infantry Regiment, were lost during the battle, and this made it difficult for historians to either analyze the events in detail or to assess the exact battle damage and losses incurred.[205] However, it was later approximated that the US 2nd Infantry Division had suffered 4,037 casualties, and most of its artillery pieces, 40 percent of its signal equipment, 45 percent of its crew-served weapons, 30 percent of its vehicles were lost during the battle.[206] Thus, the US 2nd Infantry Division was deemed to be crippled,[207] and Keiser was relieved from command by the end of the battle.[208] The other US unit that had reported significant losses was the US 25th Infantry Division with 1,313 casualties.[209] The Turkish Brigade had also reported 936 casualties with 90 percent equipment, 90 percent vehicle and 50 percent artillery losses,[210] and the brigade was rendered combat ineffective.[173] The South Korean casualties could not be estimated due to the complete absence of South Korean records during the first half of the Korean War,[211] but according to Paik, the ROK II Corps' headquarters was forced to disband in the aftermath of the battle.[212] As for Chinese losses, Peng estimated 45,000 casualties by the end of the battle,[213] and the official Chinese history attributed 20,000 casualties to combat, while the rest were attributed to the lack of adequate winter clothing and the lack of food.[11] For its role in setting up the Gauntlet against the US 2nd Infantry Division, the PVA 38th Corps was awarded the title "Ten Thousand Years Corps" by Peng on December 1, 1950.[214]

With the US 2nd Infantry Division, the Turkish Brigade and the ROK II Corps out of action, the US Eighth Army was reduced to just two corps, composed of four divisions and two brigades.[215] Meanwhile, the over-extended Chinese logistics system had also left the victorious 13th Army half-starved and incapable of any further offensive operations.[216][217] But during the chaotic UN retreats, no reconnaissance was conducted to determine the state of the Chinese forces.[2] As the result, Walker ordered the Eighth Army to abandon North Korea on December 3,[215][218] much to the surprise of the Chinese commanders.[219] The following 120 mi (190 km) withdrawal to the 38th parallel is often referred to as "the longest retreat in US military history."[220][221][222] Aside from extremely low morale after the battle, the entire Eighth Army was also gripped with "bug out fever" during the retreat,[223] and a song called the "Bugout Boogie" was composed to commemorate the Eighth Army's defeat.[224] Walker died two days before the Christmas of 1950, and Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway assumed the command of the US Eighth Army.[225] At the UN, all hopes for a unified Korea were abandoned, and a ceasefire at the 38th parallel was proposed to China on December 11, 1950.[226]

Having decisively won the battle and once again turned the tide of the war in favor of the Communists,[1] the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River represented the peak of the Chinese military's performance in Korea.[227] However, Mao interpreted the UN ceasefire as a weakness that China should further exploit.[228] Against advice from Peng and other senior military leaders,[228] Mao ordered the PVA to invade South Korea—a mission that was beyond the Chinese military's abilities while breaking the fragile Chinese supply lines.[227] Recognizing the Chinese difficulties,[217] Ridgway then led the Eighth Army to inflict severe losses on the PVA during the Chinese offensives of 1951.[13]

See also

- History of the People's Liberation Army

- History of the United States Army

- Military history of Turkey

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ This is the total US army casualty number between November 25 to December 15, 1950, minus the numbers from the 3rd and the 7th Infantry Division at the Chosin Reservoir. See Ecker 2005, p. 62.

- ↑ Xue stated that the total Chinese casualties during the Second Phase Campaign were 30,000 battle casualties and 50,000 non-battle casualties, with 10,000 battle casualties and 30,000 non-battle casualties incurred at the Eastern Sector. This would place 20,000 battle casualties and 20,000 non-battle casualties at the Western Sector. See Xue 1990, p. 59-60.

- ↑ The Eastern Sector is the Battle of Chosin Reservoir.

- ↑ In Chinese military nomenclature, the term "Army" (军) means Corps, while the term "Army Group" (集团军) means Army.

- ↑ Official Chinese history claimed that 115 black soldiers from the Task Force Wilson's C Company were captured intact as a unit, but military historian Roy Appleman believed that those soldiers were from the missing C Company of the US 24th Infantry Regiment. See Appleman 1989, p. 139.

- ↑ The other two battalions of the US 24th Infantry Regiment drifted into the US 9th and 27th Infantry Regiment's sectors after heavy Chinese attacks, and both battalions were attached to other regiments for the rest of the battle. How those two battalions became separated from the 24th Infantry Regiment is unclear due to the communication breakdown and the loss of all records. See Appleman 1989, p 142.

- Citations

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1989, p. 75.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 354.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 201.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 Roe 2000, p. 233.

- 1 2 3 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 90.

- ↑ Ecker 2005, p. 62.

- ↑ "Korean War (Kore Savaşi)" (in Turkish). Turkish War Veterans Association. Archived from the original on 2012-05-23. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- 1 2 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 283.

- ↑ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 110.

- 1 2 Xue 1990, pp. 59, 60.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 57.

- 1 2 Millett, Allan R. (2009). "Korean War". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ↑ Roe 2000, pp. 145, 150.

- ↑ Roe 2000, pp. 174, 176.

- ↑ Roe 2000, p. 176.

- ↑ Alexander 1986, p. 287.

- ↑ Roe 2000, p. 207.

- ↑ Roe 2000, p. 224.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 24.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 24, 33.

- ↑ Roe 2000, p. 229.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, pp. 86–88.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Roe 2000, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, pp. 90, 92.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 45.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 3.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 27, 76.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 40, 76.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 76.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 40, 47–48.

- 1 2 3 4 Appleman 1989, p. 203.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 48.

- ↑ Halberstam 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ Roe 2000, p. 133.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 Roe 2000, p. 242.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 69–73.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1989, p. 18.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 37.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Appleman 1992, p. 720.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 102, 104.

- 1 2 3 Roe 2000, p. 234.

- 1 2 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 61.

- ↑ Alexander 1986, p. 304.

- ↑ Shrader 1995, pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 102.

- ↑ Alexander 1986, pp. 310–311.

- ↑ Shrader 1995, p. 182.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 17–18.

- 1 2 Roe 2000, p. 276.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 74.

- ↑ Roe 2000, p. 280.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 230.

- 1 2 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 236.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 230–231, 237.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 231.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 238.

- ↑ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, pp. 95–96.

- 1 2 3 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 92.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 79.

- 1 2 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 232.

- 1 2 3 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 95.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 233.

- 1 2 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 235.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 81.

- 1 2 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 237.

- 1 2 3 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 96.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 238, 240.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 240.

- 1 2 3 4 Appleman 1989, p. 85.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 239.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 241.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 80.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 242.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 83.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 86.

- 1 2 Roe 2000, p. 283.

- 1 2 3 Roe 2000, p. 282.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1989, p. 154.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 53.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 155.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 97.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 156.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 187.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 169.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 169–174.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 175.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 179.

- ↑ Mahoney 2001, p. 54.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 185.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 180.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 186.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 190.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 188–189.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 189.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 156, 188.

- ↑ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 98.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 192.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, pp. 66, 80.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 193.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 197–198.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 200.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1989, p. 50.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 51.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 51, 104.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 50, 103.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 140.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 52.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 104–106.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 63.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 106.

- 1 2 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 99.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 107.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 109, 111.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 138, 140.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 112.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 114.

- 1 2 3 4 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 100.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 115.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1989, p. 120.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 118.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 124.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 121, 123.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 122.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 128.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 130.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 136.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 223.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 224.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 148.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Appleman 1989, p. 150.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 151.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 134–145.

- 1 2 3 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 101.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 145.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 136, 152.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 152.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 135.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 153.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 4 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 102.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 88.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 251.

- 1 2 3 Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 252.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 104.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 91.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 91, 200.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1989, p. 206.

- 1 2 Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 103.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 109.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 212.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 214.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 104.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 105.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 220.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 230.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1989, p. 207.

- 1 2 Mossman 1990, p. 110.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 112.

- ↑ Roe 2000, p. 289.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 209.

- 1 2 3 Appleman 1989, p. 92.

- ↑ Farrar-Hockley 1990, p. 333.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 82.

- ↑ Roe 2000, p. 285.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 243.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 94

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 98

- ↑ Roe 2000, p. 290.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 205.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 93.

- ↑ Farrar-Hockley 1990, p. 334.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 229.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 227.

- ↑ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 107.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 238.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 265.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 234.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 235.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 242.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 243.

- ↑ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, pp. 263–264.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 245.

- ↑ Farrar-Hockley 1990, p. 335.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 122.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 246.

- ↑ Mossman 1990, p. 123.

- 1 2 3 4 Roe 2000, p. 291.

- 1 2 Roe 2000, p. 292.

- 1 2 Appleman 1989, p. 275.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 271.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 270.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 303.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. xv, 142, 285.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 289.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 285.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 290–291.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 287.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 288–289.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 403.

- ↑ Paik 1992, p. 111.

- ↑ Zhang 1995, p. 123.

- ↑ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 108.

- 1 2 Mossman 1990, p. 150.

- ↑ Roe 2000, p. 378.

- 1 2 Shrader 1995, p. 174.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, p. 312.

- ↑ Roe 2000, p. 367.

- ↑ Alexander 1986, p. 319.

- ↑ Malkasian 2001, p. 8.

- ↑ Varhola 2000, p. 14.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 383–384.

- ↑ Dickson 2004, p. 238.

- ↑ Appleman 1989, pp. 390, 397.

- ↑ Alexander 1986, p. 375.

- 1 2 Ryan, Finkelstein & McDevitt 2003, p. 130.

- 1 2 Ryan, Finkelstein & McDevitt 2003, p. 131.

References

- Alexander, Bevin R. (1986), Korea: The First War We Lost, New York, NY: Hippocrene Books, Inc, ISBN 978-0-87052-135-5

- Appleman, Roy (1989), Disaster in Korea: The Chinese Confront MacArthur, 11, College Station, TX: Texas A and M University Military History Series, ISBN 978-1-60344-128-5

- Appleman, Roy (1992), South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, ISBN 0-16-035958-9

- Chae, Han Kook; Chung, Suk Kyun; Yang, Yong Cho (2001), Yang, Hee Wan; Lim, Won Hyok; Sims, Thomas Lee; Sims, Laura Marie; Kim, Chong Gu; Millett, Allan R., eds., The Korean War, Volume II, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-7795-3

- Chinese Military Science Academy (2000), History of War to Resist America and Aid Korea (抗美援朝战争史) (in Chinese), Volume II, Beijing: Chinese Military Science Academy Publishing House, ISBN 7-80137-390-1

- Dickson, Paul (2004), War Slang: American Fighting Words and Phrases Since the Civil War, Riverside, NJ: Brassey's Inc, ISBN 978-1-57488-710-5

- Ecker, Richard E. (2005), Korean Battle Chronology: Unit-by-Unit United States Casualty Figures and Medal of Honor Citations, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, ISBN 0-7864-1980-6

- Farrar-Hockley, Anthony (1990), Official History: The British Part in the Korean War, Volume I, London, England: HMSO, ISBN 0-11-630953-9

- Halberstam, David (2007), The Coldest Winter – America and the Korean War, New York, NY: Hyperion, ISBN 978-1-4013-0052-4

- Mahoney, Kevin (2001), Formidable Enemies: The North Korean and Chinese Soldier in the Korean War, Novato, CA: Presidio Press, ISBN 978-0-89141-738-5

- Malkasian, Carter (2001), The Korean War 1950-1953, New York, NY: Osprey Publishing Ltd., ISBN 1-84176-282-2

- Mossman, Billy C. (1990), Ebb and Flow: November 1950-July 1951, United States Army in the Korean War, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, ISBN 978-1-4102-2470-5

- Paik, Sun Yup (1992), From Pusan to Panmunjom, Riverside, NJ: Brassey Inc, ISBN 0-02-881002-3

- Roe, Patrick C. (2000), The Dragon Strikes, Novato, CA: Presidio, ISBN 0-89141-703-6

- Ryan, Mark A.; Finkelstein, David M.; McDevitt, Michael A. (2003), Chinese Warfighting: The PLA Experience Since 1949, Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 0-7656-1087-6

- Shrader, Charles R. (1995), Communist Logistics in the Korean War, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-29509-3

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000), Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953, Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4

- Xue, Yan (徐焰) (1990), First Confrontation: Reviews and Reflections on the History of War to Resist America and Aid Korea (第一次较量:抗美援朝战争的历史回顾与反思) (in Chinese), Beijing: Chinese Radio and Television Publishing House, ISBN 7-5043-0542-1

- Zhang, Shu Guang (1995), Mao's Military Romanticism: China and the Korean War, 1950-1953, Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 0-7006-0723-4

Further reading

- Fehrenbach, T. R., Jr. (1963), This Kind of War, New York: Macmillan.

- Marshall, S.L.A. (1982). The River and the Gauntlet: Defeat of the Eighth Army by the Chinese Communist forces, November, 1950, in the Battle of the Chongchon River, Korea. Des Moines, IA: Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-3845-3.

- Spurr, Russell (1988). Enter the Dragon: China's Undeclared War Against the U.S. in Korea 1950–51. New York, NY: Newmarket Press. ISBN 1-55704-008-7.