Beach Pneumatic Transit

| Beach Pneumatic Transit | |||

|---|---|---|---|

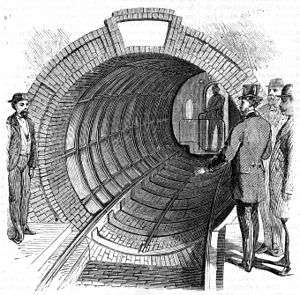

Sketch of the train car and tunnel | |||

| Overview | |||

| Type | Atmospheric railway | ||

| Locale | New York City, United States | ||

| Termini |

Warren Street and Broadway Murray Street and Broadway | ||

| Stations | 1[note 1] | ||

| Operation | |||

| Opened | 26 February 1870[1] | ||

| Closed | 1873[1] | ||

| Owner | Beach Pneumatic Transit Company | ||

| Operator(s) | Beach Pneumatic Transit Company | ||

| Rolling stock | 1 car | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 95 m (312 ft)[1] | ||

| Number of tracks | Single track | ||

| |||

The Beach Pneumatic Transit was the first attempt to build an underground public transit system in New York City. It was developed by Alfred Ely Beach in 1869 as a demonstration subway line running on pneumatic power. As the subway line had one stop and a one-car shuttle going back and forth, it was merely a novelty and not a regular mode of transport. It lasted from 1870 until 1873.

History

Alfred Ely Beach demonstrated a model of basic pneumatic subway system, in which air pressure in the tube pushed the cars, at the American Institute Exhibition in New York in 1867.[2] After demonstrating that the model was viable, in 1869 Beach and his Beach Pneumatic Transit Company began constructing a pneumatically-powered subway line beneath Broadway. Funneled through a company he set up, Beach put up $350,000 of his own money to bankroll the full-scale test project.[3] Built with a tunneling shield,[2] the tunnel was complete in only 58 days.[1] Its single tunnel, 312 feet (95 m) long, 8 feet (2.4 m) in diameter, was completed in 1870 and ran under Broadway from Warren Street to Murray Street.[2][4]

However, one of the city's top politicians of the day, William "Boss" Tweed, would not support such a project. With no initial political support for the project, Beach started the project by claiming he was building postal tubes. The initial permit was to install a pair of smaller postal tubes below Broadway; however, Tweed later amended the permit to allow the excavation of a single large tunnel wherein the smaller tubes could reside.[5]:12–13[6] The exact location of the tubes was determined during construction by compass and survey as well as verified by driving jointed rods of iron up through the roof of the tunnel to the pavement.[7] The line was built as a demonstration of a pneumatic transit system, open to the public with a 25-cent fare per person.[2] Proceeds for the admission went to the Union Home and School for Soldiers' and Sailors' Orphans.[8] It was planned to run about 5 miles (8.0 km) in total, to Central Park, if it were ever completed.[5]:11

For the public, the project was basically an attraction. It ran only a single car on its one-block-long track to a dead-end at its terminus, and passengers would simply ride out and back, to see what the proposed subway might be like. During its first two weeks of operation, the Beach Pneumatic Transit sold over 11,000 rides, and over 400,000 total rides in its single year of operation.[6][9][10] Although the public showed initial approval, Beach was delayed in getting permission to expand it due to official obstruction for various reasons. By the time he finally gained permission in 1873, public and financial support had waned, and the subway was closed down within the year.[10] The project was shut down when a stock market crash caused investors to withdraw support. It is unclear that such a system could have been practical for a large-scale subway network.[2][5]:14[11]

After the project was shut down, the tunnel entrance was sealed and the station, built in part of the basement of the Rogers Peet Building, was reclaimed for other uses. The entire building was lost to fire in 1898.[12] In 1912, workers excavating for the present-day BMT Broadway Line dug into the old Beach tunnel, where they found the remains of the car, the tunnelling shield used during initial construction, and even the piano in the subway's waiting room.[2][10] The shield was removed and donated to Cornell University, which has since lost track of its whereabouts.[13] The tunnel was almost completely within the limits of the present day City Hall station under Broadway, but it is rumored that a small portion could still be accessed by a manhole on Reade Street.[14] The New-York Historical Society commissioned a plaque honoring Alfred Beach to be placed in the City Hall station.[3][6]

Although the Beach Pneumatic Transit lasted for only three years, the project gave way to the New York pneumatic tube mail system, which was based on the request that Beach had made to Tweed and which ran until 1953.[5]:14

Design

Aesthetics

It was designed as a very ornate project. The station was adorned with frescoes and easy chairs. Zirconia lamps revealed the luxurious interior of the station.[15] There were statues and a gold fish pond in the station that people could look at while they waited for their turn to enter the ride.

Technical specs

The car could hold 22 people[16] and the riders would enter the site at Devlin's Clothing Store, a well known shop, located at 260 Broadway, on the southwest corner of Warren Street.[8][17][18]

The ride was controlled by a 48 short tons (44 t) Roots blower,[6] nicknamed "the Western Tornado", built by "Roots Patent Force Rotary Blowers" (see Roots Blower Company). When the car reached the end, baffles on the blower system were reversed and the car was pulled back by the suction.[16]

Related developments

The Crystal Palace pneumatic railway was a similar but longer system which operated in 1864 on the grounds of The Crystal Palace in London.[19]

In 2013, entrepreneur Elon Musk proposed a Hyperloop system, which would propel capsules through tubes at high speeds using pressurized air.[2]

In popular culture

- The 1973 novel The Taking of Pelham One Two Three by Morton Freedgood (under the pen name John Godey) features a character speculating on Beach's tunnel as a possible escape route for four men who have hijacked a subway car and demanded ransom for its passengers. The history of Beach's project is briefly described, but is ultimately unrelated to the criminals' escape plan.

- In the 1989 movie Ghostbusters II, it is referred to as the New York Pneumatic Railroad (NYPRR). The film depicts the fictional Van Horne Station beneath the intersection of East 77th Street and First Avenue, where a subterranean river of ectoplasm flows through its tunnels toward the fictional Manhattan Museum of Art. It is interesting to note that the building used for filming the Manhattan Museum of Art's exterior was actually the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House near Battery Park, which is within a mile of the original Beach Pneumatic Transit's tunnel location.[20] The station shown in the movie is based on the closed City Hall Station which is adjacent to the actual pneumatic system's location.

- Neal Schusterman's Young Adult Novel Downsiders makes many references to the Beach Pneumatic Transit.

- The novel Faces in the Crowd by William Marshall depicts the abandoned station and tunnel as the headquarters of a criminal plot.

- The song Sub-Rosa Subway on the first album by the Canadian rock band Klaatu, titled: 3:47 EST, is about Beach's subway.

- The film An American Tail: The Treasure of Manhattan Island involves the main characters Fievel Mouskewitz and Tony Toponi exploring a series of caverns directly beneath one of the abandoned terminals for the Pneumatic Transit system.

- The comic book Atomic Robo Volume 6: The Deadly Art of Science depicts an entire network of pneumatic transit tubes running beneath Manhattan. Constructed in part by Nikola Tesla, the system was shut down for not being built "according to code" and is not part of common public knowledge.

- In the Brian K. Vaughan comic book, Ex Machina, issue #43 has ex-superhero-turned-Mayor of New York, Mitchell Hundred, describing Beach's project to his deputy mayor. Later, in issue #44, the remains of the Beach Pneumatic Transit tunnel become the site of a confrontation between Hundred and a parallel universe automaton who reveals the source of Hundred's powers, while chastising him for failing to prepare his world for an extradimensional conquest. This was part of the series' Ring Out The Old story arc, whose contents appear in the trade paperback Ex Machina Vol. 9: Ring Out the Old (ISBN 1-4012-2694-9) and Ex Machina: The Deluxe Edition Book Five' (ISBN 1-4012-2999-9).

- In "Wormquake!", a second season episode of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Donatello makes mention of the pneumatic subway while he, along with April O'Neil and Casey Jones, are searching the sewers and subway system.

- In Libba Bray's 2015 novel, "Lair of Dreams," the Beach Pneumatic Transit tunnel plays an important part in the plot, mentioning many of the facts related to the real tunnel and stations while set in the 1920s in the paranormal young adult novel.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ The terminus at Murray Street was a dead-end, not a station

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 "www.nycsubway.org". www.nycsubway.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Santora, Marc (August 14, 2013). "When the New York City Subway Ran Without Rails". The New York Times.

- 1 2 "Inventor of the Week - Alfred Beach" (MIT)

- ↑ Brennan, Joseph (2005). "They found the tube in excellent condition". Beach Pneumatic. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- 1 2 3 4 Diehl, Lorraine (2004). The Tracks that Built New York City. New York. ISBN 9781400052271.

- 1 2 3 4 "The remarkable pneumatic people mover" on Damn Interesting

- ↑ "To excavate the Earth" (Columbia University)

- 1 2 Beach Pneumatic Transit on capsu.org website

- ↑ "The Secret Subway" (PBS)

- 1 2 3 Martin, Douglas (November 17, 1996). "Subway Planners' Lofty Ambitions Are Buried as Dead-End Curiosities". nytimes.com. The New York Times. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ "Beach Pneumatic Transit - The Interborough Rapid Transit subway" (plrog.org)

- ↑ Barry, Keith (2010-02-26). "Feb. 26, 1870: New York City Blows Subway Opportunity". Wired.

- ↑ Worthington, George (12 Dec 1912). "A Subway Relic". Electrical Review and Western Electrician. 61: 1137.

- ↑ "Top 12 Secrets of the NYC Subway". Untapped Cities.

- ↑ "The Pneumatic Mail Tubes" (USPS)

- 1 2 "Frederic Delaitre's Lost Subways / Beach Pneumatic Subway". sfr.fr.

- ↑ Super User. "Alfred Ely Beach and NYC's First Subway". Alfred Ely Beach and NYC's First Subway.

- ↑ "They found the tube in excellent condition" (Columbia University)

- ↑ Delaitre, Frédéric (2002-07-10). "Crystal Palace Atmospheric Railway". Lost Subways. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ↑ Ghostbusters II at the Internet Movie Database

Further reading

- Most, Doug, The Race Underground : Boston, New York, and the incredible rivalry that built America's first subway (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2014), ISBN 9780312591328.

- The First New York Subway: Beach Pneumatic Transit Sometimes Interesting. 19 May 2012

- The Secret Subway: Episode of American Experience about the subway

- No. 1474: Beach's Secret Subway: Episode of The Engines of Our Ingenuity about the subway

- "Pneumatic Transit" Animation by Abby Digital

- The Beach Pneumatic Transit Company - Just a Bunch of Hot Air? from the Museum of the City of New York Collections blog

- Beach, Alfred Ely (March 5, 1870). "The Pneumatic Tunnel Under Broadway, N.Y.". Scientific American. 22 (10): 154–156. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican03051870-154.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beach Pneumatic Transit. |

- "Beach Pneumatic Transit" at Abandoned Stations, by Joseph Brennan

- "Beach Pneumatic Transit" on nycsubway.org

Coordinates: 40°42′48″N 74°00′25″W / 40.71332°N 74.00701°W