Belgium in World War I

The history of Belgium in World War I traces Belgium's role between the German invasion in 1914, through the continued military resistance and occupation of the territory by German forces, known as the Rape of Belgium, to the armistice in 1918, as well as the role it played in the international war effort through its African colony and small force on the Eastern Front.

Background

German invasion

.jpg)

When World War I began, Germany invaded neutral Belgium and Luxembourg as part of the Schlieffen Plan, in an attempt to capture Paris quickly by catching the French off guard by invading through neutral countries. It was this action that technically caused the British to enter the war, as they were still bound by the 1839 agreement to protect Belgium in the event of war. On 2 August 1914, the German government demanded that German armies be given free passage through Belgian territory, although this was refused by the Belgian government on 3 August.[1] On 4 August, German troops invaded Belgium.[2]

It is widely claimed that the Belgian army's resistance during the early days of the war, with the army – around a tenth the size of the German army – holding up the German offensive for nearly a month, gave the French and British forces time to prepare for the Marne counteroffensive later in the year.[3] In fact, the German advance on Paris was almost exactly on schedule.

The German invaders treated any resistance—such as demolition of bridges and rail lines—as illegal and subversive, shooting the offenders and burning buildings in retaliation.[4]

Flanders was the main base of the British army and it saw some of the greatest loss of life on both sides of the Western Front.

German occupation 1914–18

The Germans governed the occupied areas of Belgium (over 95% of the country) while a small area around Ypres remained under Belgian control. An occupation authority, known as the General Government, was given control over the majority of the territory although the two provinces of East and West Flanders were given separate status as a war zone under the direct control of the German army. Elsewhere martial law prevailed. For the majority of the occupation, the German military governor was Moritz von Bissing (1914–17). Beneath the governor was a network of regional and local German kommandanturen and each locality was under the ultimate control of a German officer.[5]

Many civilians fled the war zones to safer parts of Belgium. Many refugees from all over the country went to the Netherlands (which was neutral) and about 300,000 to France. Over 200,000 went to Britain, where they resettled in London and found war jobs. The British and French governments set up the War Refugees Committee (WRC) and the Secours National, to provide relief and support; there were an additional 1,500 local WRC committees in Britain. The high visibility of the refugees underscored the role of Belgium in the minds of the French and British.[6][7] In the spring of 1915, German authorities started construction on the Wire of Death, a lethal electric fence along the Belgian-Dutch border which would claim the lives of between 2,000 and 3,000 Belgian refugees trying to escape the occupied country.[8]

On the advice of the Belgian government in exile, civil servants remained in their posts for the duration of the conflict, carrying out the day-to-day functions of government. All political activity was suspended and Parliament shut down. While farmers and coal miners kept up their routines, many larger businesses largely shut down, as did the universities. The Germans helped set up the first solely Dutch-speaking university in Ghent. The Germans sent in managers to operate factories that were underperforming. Lack of effort was a form of passive resistance; Kossmann says that for many Belgians the war years were "a long and extremely dull vacation."[9] Belgian workers were conscripted into forced labour projects; by 1918, the Germans had deported 120,000 Belgian workers to Germany.[10]

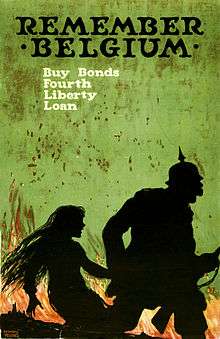

The Rape of Belgium

The German army was outraged at how Belgium had frustrated the Schlieffen Plan to capture Paris. From top to bottom there was a firm belief that the Belgians had unleashed illegal saboteurs (called "Francs-tireurs") and that civilians had tortured and maltreated German soldiers. The response was a series of multiple large-scale attacks on civilians and the destruction of historic buildings and cultural centers. The German army executed between 5,500 and 6,500[11] French and Belgian civilians between August and November 1914, usually in near-random large-scale shootings of civilians ordered by junior German officers. Individuals suspected of partisan activities were summarily shot. Historians researching German Army records have discovered 101 "major" incidents—where ten or more civilians were killed—with a total of 4,421 executed. Historians have also discovered 383 "minor" incidents that led to the deaths of another 1,100 Belgians. Almost all were claimed by Germany to be responses to guerrilla attacks.[12] In addition some high-profile Belgian figures, including politician Adolphe Max and historian Henri Pirenne, were imprisoned in Germany as hostages.

The German position was that widespread sabotage and guerrilla activities by Belgian civilians were wholly illegal and deserved immediate harsh collective punishment. Recent research that systematically studied German Army sources has demonstrated that they in fact encountered no irregular forces in Belgium during the first two and a half months of the invasion. The Germans were responding instead to a phantom fear they had unconsciously created themselves.[13]

Bryce Report and international response

The British were quick to tell the world about German atrocities. Britain sponsored the "Committee on Alleged German Outrages" known as the Bryce Report. Published in May 1915, the Report provided elaborate details and first-hand accounts, including excerpts from diaries and letters found on captured German soldiers. The Report was a major factor in changing public opinion in neutral countries, especially the United States. After Britain shipped 41,000 copies to the US, the Germans responded with their own report on atrocities against German soldiers by Belgian civilians.[14]

The Bryce Report was ridiculed in the 1920s and 1930s and afterwards as highly exaggerated wartime propaganda. It relied too heavily on unproven allegations of refugees and distorted interpretations of diaries of German soldiers.[15] Recent scholarship has not tried to validate the statements in the Bryce Report. Instead research has gone into the official German records and have confirmed that the Germans committed large-scale deliberate atrocities in Belgium.[16]

International relief

Belgium faced a food crisis and an international response was organized by an American engineer based in London, Herbert Hoover, on the request of Émile Francqui, whose Comité National de Secours et d'Alimentation (CNSA) realized that the only way to avoid a famine in Belgium was through imports from overseas.[17] Hoover's Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) received the permission of both Germany and the Allies for their activities.[18] As chairman of the CRB, Hoover worked with Francqui to raise money and support overseas, transporting food and aid to Belgium which was then distributed by the CNSA. The CRB purchased and imported millions of tons of foodstuffs for the CN to distribute, and watched over the CN to make sure the German army did not appropriate the food. The CRB became a veritable independent republic of relief, with its own flag, navy, factories, mills, and railroads. Private donations and government grants (78%) supplied an $11-million-a-month budget.[19]

At its peak, the American arm, the American Relief Administration (ARA) fed 10.5 million people daily. Great Britain became reluctant to support the CRB, preferring instead to emphasize Germany's obligation to supply the relief; Winston Churchill led a military faction that considered the Belgian relief effort "a positive military disaster." [20]

Internal politics

The prewar Catholic ministry remained in office as a government in exile with Charles de Broqueville continuing as prime minister and also taking on the war portfolio. Viscount Julien Davignon continued as foreign minister until 1917, when de Broqueville gave up the war ministry and took over foreign affairs. The government was broadened to include all parties, as politics were suspended for the duration; of course, no elections were possible. The two main opposition leaders, Paul Hymans of the Liberals and Emile Vandervelde of the Labour party, became ministers without portfolio in 1914. In a cabinet shakeup in May 1918, de Broqueville was excluded altogether. The government was based in the French city of Le Havre, but communications with the people behind German lines were difficult and roundabout. The government in exile did not govern Belgium, and so its politicians instead squabbled endlessly, and plotted unrealistic foreign policy moves, such as the annexation of Luxembourg or a slice of the Netherlands after the war.[21]

Belgium was not officially one of the Allies. In turn they did not consult with Belgium, but Britain, France and Russia formally pledged in 1916 that "when the moment comes, the Belgian government will be called to participate in the peace negotiations and that they will not put an end to the hostilities unless Belgium is re-established in its political and economic independence and largely indemnified for the damage which she has undergone. They will lend their aid to Belgium to assure her commercial and financial rehabilitation."[22]

Flemish identity

Flemish consciousness of their national identity grew through the events and experiences of war. The German occupying authorities, under Von Bissing and influenced by pre-war Pan-Germanism, viewed the Flemish as an oppressed people and launched a policy to appeal to the demands of the Flemish Movement which had emerged in the late 19th century. These measures were collectively known as the Flamenpolitik ("Flemish Policy"). From 1916, the Germans sponsored the creation of "Von Bissing University" which was the first university that taught in Dutch language. Dutch was also introduced as the language of instruction in all state-supported schools in Flanders in 1918. The German measures split the Movement between the "activists" or "maximalists", who believed that using German support was their only chance to realize their objectives, and the "passivists" who opposed German involvement. In 1917, the Germans created the Raad van Vlaanderen ("Council of Flanders") as a quasi autonomous government in Flanders composed of "activists". In December 1917, the council attempted to achieve Flemish independence from Belgium but the defeat of Germany in the war meant that they never achieved success. After the war, many "activists" were arrested for collaboration.

Independently, among the Belgian soldiers on the Yser Front, the Flemish Frontbeweging ("Front Movement") was formed from Flemish soldiers in the Belgian army to campaign for greater use of the Dutch language in education and government, although it was not separatist.[23] Kossmann concludes that the German policy of fostering separatism in Flanders was a failure because it did not win popular support.[24]

Belgian military operations

Belgium was poorly prepared for war. Strict neutrality meant there was no coordination of any kind with anyone. It had a new, inexperienced general staff. It started compulsory service in 1909; the plan was to have an army of 340,000 men by 1926. In 1914 the old system had been abandoned and the new one was unready, lacking trained officers and sergeants, as well as modern equipment. The army had 102 machine guns and no heavy artillery. The strategy was to concentrate near Brussels and delay a German invasion as long as possible—a strategy that in the event proved highly effective as it disrupted the German timetable. For example, the German timetable required the capture of the railway center of Liège in two days; it took 11.[25][26]

Much of the small army was captured early on as the frontier forts surrendered. In late 1914 the king had only 60,000 soldiers left.[27] During the war a few young men volunteered to serve, so by 1918 the total force had returned to 170,000. That was far too few to launch a major offensive. The Germans had nothing to gain from an attack, so the short Belgian front was an island of relative calm as gigantic battles raged elsewhere on the Western Front. The total of Belgian soldiers killed came to about 2.0% of its eligible young men (compared to 13.3% in France and 12.5% in Germany).[28]

Yser Front

King Albert I stayed in the Yser as commander of the military to lead the army while the Belgian government, under Charles de Broqueville withdrew to Le Havre in France.

Belgian soldiers fought a number of significant delaying actions in 1914 during the initial invasion. At the Battle of Liège, the town's fortifications held off the invaders for over a week, buying valuable time for Allied troops to arrive in the area. Additionally, the German "Race to the Sea" was stopped dead by exhausted Belgian forces at the Battle of the Yser. The dual significance of the battle was that the Germans were unable to complete their occupation of the entire country, and the Yser area remained unoccupied. The success was a propaganda coup for the Belgian army.[29]

Belgian troops continued to hold the same sector of frontline, known as the Yser Front and by now a part of the main Western Front, until 1918, a fact that provided a propaganda coup to the Belgian forces on the Western Front for the duration of the war.[29]

Belgian Congo and the East Africa Campaign

German presence in Africa posed no direct threat to the Belgian Congo; however, in 1914 a German gunboat sank a number of Belgian vessels on Lake Tanganyika.[30] Congolese forces, under Belgian officers, fought German colonial forces in the Cameroons and seized control of the western third of German East Africa, advancing as far as the town at Tabora. The League of Nations in 1925 made Belgium the trustee of this territory (modern Rwanda and Burundi) as the mandate of Ruanda-Urundi.

Eastern Front

The Belgian Expeditionary Corps was a small armoured car unit; it was sent to Russia in 1915 and fought on the Eastern Front. The Minerva armoured car were used for reconnaissance, long distance messaging and carrying out raids and small scale engagements. 16 Belgians were killed in action.[31]

Aftermath

Postwar settlements

King Albert I went to the Paris Peace Conference in April 1919, where he met with the Big Four and the other leaders of France, Italy, Britain and the United States. He had four strategic goals: 1) to restore and expand the Belgian economy, using cash reparations from Germany; 2) to assure Belgium's security by the creation of a new buffer state on the left bank of the Rhine; 3) to revise the obsolete treaty of 1839; and 4) to promote a 'rapprochement' between Belgium and the Grand duchy of Luxembourg.

He strongly advised against a harsh, punitive treaty against Germany that would eventually provoke German revenge.[32] He also considered that the dethronement of the princes of Central Europe and, in particular, the dissolution of the Habsburg Empire would constitute a serious menace to peace and stability on the continent.[33] The Allies considered Belgium to be the chief victim of the war, and it aroused enormous popular sympathy, but the King's advice played a small role in Paris.[34]

Belgium was given much less than it wanted, with a total payment of three billion German gold marks (about $500 million); the money did not stimulate the lethargic Belgian economy of the 1920s. Belgium also received a small slice of territory in the east of the country (known as Eupen-Malmedy) from Germany, which remains part of the country to this day. Its demands for a slice of Zeeland in the Netherlands (which had remained neutral during the conflict, but was widely believed to have collaborated with Germany), were rejected and led to ill-will. Britain was willing to guarantee Belgian borders only if it committed to neutrality, which Albert rejected. Instead, Belgium became a junior partner with France in an occupation of part of Germany under a 1920 Treaty. Belgium was also given a League of Nations trusteeship over the former German colonies in Africa of Rwanda and Burundi.[35] On the whole, Belgian diplomacy was poorly handled and ineffective.[36]

Between 1923 and 1925, Belgian and French soldiers occupied the Ruhr to force the Weimar government to maintain payment of reparations.

Commemoration

Due to the hundreds of thousands of British and Canadian casualties, the blood-red red poppies that sprang up in no man's land when fields were torn up by artillery were immortalized in the 1915 poem In Flanders Fields. In the British Empire and America, poppies became a symbol of human life lost in war and were adopted as an emblem of remembrance from 1921.

The suffering of Flanders is still remembered by Flemish organizations during the yearly Yser pilgrimage and "Wake of the Yser" in Diksmuide at the monument of The Yser tower.

British veterans and civilians in the 1920s created a shrine of sacrifice in Belgium. The city of Ypres was made the symbol of all Britain was fighting for and was given an almost sacred aura. The Ypres League transformed the horrors of trench warfare into a spiritual quest in which British and imperial troops were purified by their sacrifice. After the war Ypres became a pilgrimage destination for Britons to imagine and share the sufferings of their men and gain a spiritual benefit.[37]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Belgium in World War I. |

Notes

- ↑ "German Request for Free Passage through Belgium, and the Belgian Response, 2–3 August 1914". www.firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ↑ "World War I: Belgium". histclo.com. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ Barbara W. Tuchman, The Guns of August (1962) pp 191–214

- ↑ Spencer Tucker, ed., The European Powers in the First World War (1999) pp 114–20

- ↑ Léon van der Essen, A short history of Belgium (1920) pp 174–5

- ↑ Pierre Purseigle, "'A Wave on to Our Shores': The Exile and Resettlement of Refugees from the Western Front, 1914–1918," Contemporary European History (2007): 16#4 pp 427–444, [online at Proquest]

- ↑ Peter Cahalan, Belgian Refugee Relief in England during the Great War (New York: Garland, 1982);

- ↑ "De Dodendraad - Wereldoorlog I". Bunkergordel.be. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ E.H. Kossmann, The Low Countries: 1780–1940(1978) p 525, 528–9

- ↑ Bernard A. Cook, Belgium: a history (2002) pp. 102–7

- ↑ John Horne and Alan Kramer, German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial (Yale U.P. 2001)

- ↑ Horne and Kramer. German Atrocities 1914. pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Horne and Kramer. German Atrocities 1914. p. 77.

- ↑ Patrick J. Quinn (2001). The Conning of America: The Great War and American Popular Literature. Rodopi. p. 39.

- ↑ Trevor Wilson, "Lord Bryce's Investigation into Alleged German Atrocities in Belgium, 1914–1915," Journal of Contemporary History (1979) 14#3 pp 369–383.

- ↑ John Horne and Alan Kramer, German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial (Yale University Press, 2002); Larry Zuckerman, The Rape of Belgium: The Untold Story of World War I (NYU Press, 2004); Jeff Lipkes, Rehearsals: The German Army in Belgium, August 1914 (Leuven University Press, 2007)

- ↑ George H. Nash, The Life of Herbert Hoover: The Humanitarian, 1914–1917 (1988)

- ↑ David Burner, Herbert Hoover: A Public Life (1996) p. 74.

- ↑ Burner, Herbert Hoover p. 79.

- ↑ Burner, p. 82.

- ↑ Sally Marks, Innocent Abroad p 21-35

- ↑ Sally Marks, Innocent Abroad p 24

- ↑ Cook, Belgium: a history pp. 104–5

- ↑ Kossmann, The Low Countries: 1780–1940 (1978) p 528

- ↑ Hew Strachen, The First World War: Volume I: To Arms (2001) 1:208-12, 216

- ↑ Emile Joseph Galet and Ernest Swinton, Albert King of the Belgians in the Great War (1931), pp 73–106

- ↑ Kossmann, Low Countries(1978) pp 523–4

- ↑ Niall Ferguson, The Pity of War (1999) p 299

- 1 2 Spencer Tucker, ed., The European Powers in the First World War (1999) pp 116–8

- ↑ Spencer C. Tucker and Priscilla Mary Roberts, eds. (2005). World War I : A Student Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 1056.

- ↑ "Belgian Armoured Cars in Russia". Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ↑ Vincent Dujardin, Mark van den Wijngaert, et al. Léopold III

- ↑ Charles d'Ydewalle. Albert and the Belgians: Portrait of a King.

- ↑ Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919 (2003) pp 106, 272

- ↑ Sally Marks, Innocent Abroad: Belgium at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 (1991)

- ↑ Kossmann, The Low Countries pp 575–8, 649

- ↑ Mark Connelly, "The Ypres League and the Commemoration of the Ypres Salient, 1914–1940," War in History (2009) 16#1 pp 51–76, online

Further reading

- Den Hertog, Johan. "The Commission for Relief in Belgium and the Political Diplomatic History of the First World War," Diplomacy and Statecraft (2010) 21#4 pp 593–613.

- Horne, John N. and Alan Kramer. German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial (Yale University Press, 2001), online review; Summary of book.

- Kossmann, E. H. The Low Countries 1780–1940 (1978) excerpt and text search ; full text online in Dutch (use CHROME browser for automatic translation to English) pp 517–44

- Lipkes, Jeff. Rehearsals: The German Army in Belgium, August 1914 (2007) excerpt and text search

- Marks, Sally. Innocent Abroad: Belgium at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 (1991) online edition

- Pawly, Ronald. The Belgian Army in World War I (2009) excerpt and text search

- Proctor, T. M. "Missing in Action: Belgian Civilians and the First World War," Revue belge d’Histoire contemporaine (2005) 4:547–572.

- Zuckerman, Larry (2004). The Rape of Belgium: The Untold Story of World War I. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9704-4., focused on the early months

Primary sources

- Bryce Report (1915)

- Galet, Emile Joseph. Albert King of the Belgians in the Great War (1931), detailed memoir by the military visor to the King; covers 1912 to the end of October, 1914

- Gay, George I., ed. Public Relations of the Commission for Relief in Belgium: Documents (2 vol 1929) online

- Gibson, Hugh. A Journal from Our Legation in Belgium (1917) online, by American diplomat

- Hoover, Herbert. An American Epic: Vol. I: The Relief of Belgium and Northern France, 1914–1930 (1959) text search

- Hoover, Herbert. The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: Years of Adventure, 1874–1920 (1951) pp 152–237

- Hunt, Edward Eyre. War Bread: A Personal Narrative of the War and Relief in Belgium (New York: Holt, 1916.) online

- Whitlock, Brand. Belgium: a personal narrative (1920)], by U.S. ambassador online

- Charlotte Kellogg, Commission for Relief in Belgium, Women of Belgium turning tragedy to triumph (1917)

External links

- Brussels 14–18 at Brussels-Capital Region

- Articles relating to Belgium at the International Encyclopedia of the First World War