Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary

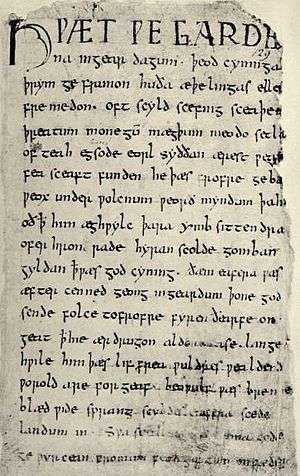

Front cover of the 2014 hardback edition, titled "Hringboga Heorte Gefysed" | |

| Editor | Christopher Tolkien |

|---|---|

| Author |

Anonymous (Beowulf) J. R. R. Tolkien (Sellic Spell) |

| Translator | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Cover artist | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English, Old English |

| Subject | Old English poetry |

| Genre | Epic poetry |

| Published | 22 May 2014 |

| Publisher |

HarperCollins Houghton Mifflin Harcourt |

| Pages | 425 (Hardback) |

| ISBN | 978-0-00-759006-3 |

| OCLC | 875629841 |

| Preceded by | The Fall of Arthur |

| Followed by | The Story of Kullervo |

Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary is a prose translation of the early medieval epic poem Beowulf from Old English to modern English language. Translated by J. R. R. Tolkien from 1920 to 1926, it was edited by Tolkien's son Christopher and published posthumously in May 2014 by HarperCollins.

In the poem, Beowulf, a hero of the Geats in Scandinavia, comes to the aid of Hroðgar, the king of the Danes, whose mead hall Heorot has been under attack by a monster known as Grendel. After Beowulf slays him, Grendel's mother attacks the hall and is then also defeated. Victorious, Beowulf goes home to Geatland in Sweden and later becomes king of the Geats. After fifty years have passed, Beowulf defeats a dragon, but is fatally wounded in the battle. After his death, his attendants bury him in a tumulus, a burial mound, in Geatland.

The translation is followed by a commentary on the poem that became the base for Tolkien's acclaimed 1936 lecture "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics".[1] Furthermore, the book includes the previously unpublished "Sellic Spell" and two versions of "The Lay of Beowulf". The former is a fantasy piece on Beowulf's biographical background while the latter is a poem on the Beowulf theme.[2]

Plot

Beowulf, a prince of the Geats, and his followers set out to help king Hroðgar of the Danes in his fight against the monster Grendel. Because Grendel hates music and noise he frequently attacks Hroðgar's mead hall Heorot killing the king's men in their sleep. While Beowulf cannot kill Grendel directly in their first encounter, he still wounds him fatally. Afterwards he has to face Grendel's mother who has come to avenge her son. Beowulf follows her to a cavern beneath a lake where he slays her with a magical sword. There he also finds the dying Grendel and decapitates him.

Beowulf returns home to become king of the Geats. After some 50 years, a dragon whose treasure had been stolen from his hoard in a burial mound begins to terrorize Geatland. Beowulf, now in his eighties, tries to fight the dragon but cannot succeed. He follows the dragon to his lair where Beowulf's young relative Wiglaf joins him in the fight. Eventually, Beowulf slays the dragon but is mortally wounded. In the end, his followers bury their king in a mound by the sea.

Reception

Tolkien's translation of Beowulf has been compared to Seamus Heaney's translation from 2000. Joan Acocella writes that since Tolkien was not a professional poet like Heaney, he had to make compromises in translating the original Old English epic. According to Acocella, Heaney's focus on rhyme and alliteration makes him occasionally lose details from the original that remain in Tolkien's prose version.[3] Tolkien's version stays closer to the details and rhythm of the original and also very close to the original sense of the poem, which has been attributed to Tolkien's scholarly knowledge of Old English, whereas Heaney, on the other hand, succeeded in producing a translation suited for the modern reader, more so than Tolkien's.[3][4]

The publication also caused some controversy among scholars. Beowulf expert and University of Kentucky professor Kevin Kiernan, called it a "travesty", and criticism was also offered by Harvard professor Daniel Donoghue.[5] Writing for Business Insider, Kiernan cites J. R. R. Tolkien himself who disliked his own translation. According to Kiernan, any prose translation of Beowulf will neglect the "poetic majesty" of the original.[6] University of Birmingham lecturer Philippa Semper instead called the translation "captivating" and "a great gift to anyone interested in Beowulf or Tolkien."[4]

Writing in the New York Times, Ethan Gilsdorf comments that Tolkien had been skeptical about putting Beowulf into modern English, and had written in his 1940 essay On Translating Beowulf that turning the poem "into 'plain prose' could be an 'abuse'."[7] Gilsdorf continues, "But he did it anyway"; Tolkien remarking that the result "was 'hardly to my liking'."[7]

Background and legacy

J. R. R. Tolkien specialized in English philology at university and in 1915 graduated with Old Norse as special subject. In 1920, he became Reader in English Language at the University of Leeds, where he claimed credit for raising the number of students of linguistics from five to twenty. He gave courses in Old English heroic verse, history of English, various Old English and Middle English texts, Old and Middle English philology, introductory Germanic philology, Gothic, Old Icelandic, and Medieval Welsh.[8] Having read Beowulf earlier, he began a translation of the poem which he finished in 1926 but never published. Acocella writes that Tolkien may not have had the time to pursue a publication when he moved to Oxford and began to write his novel The Hobbit. Tolkien's biographer Humphrey Carpenter argues also that Tolkien was too much of a perfectionist to publish his translation.[3]

Ten years later, however, Tolkien drew upon this work when he gave a lecture "Beowulf: The Monster and the Critics". According to this lecture, the true theme of Beowulf, namely death and defeat, was being neglected in favour of archaeological and philological disputes on how much of the poem was fictive or true.[3]

Influences on The Hobbit

Tolkien described Beowulf as one of the "most valued sources" for The Hobbit.[9] Certain descriptions in The Hobbit seem to have been lifted straight out of Beowulf with some minor rewording, such as when each dragon stretches out its neck to sniff for intruders.[10] Likewise, Tolkien's descriptions of the lair as accessed through a secret passage mirror those in Beowulf. Other specific plot elements and features in The Hobbit that show similarities to Beowulf include the title thief as Bilbo Baggins is called by Gollum and later also by Smaug, and Smaug's personality which leads to the destruction of Lake-town.[11] Tolkien refines parts of Beowulf's plot that he appears to have found less than satisfactorily described, such as details about the cup-thief and the dragon's intellect and personality.[12] By his naming his sword "Sting" one can see Bilbo's acceptance of the kinds of cultural and linguistic practices found in Beowulf, signifying his entrance into the ancient world in which he found himself.[13] This progression culminates in Bilbo stealing a cup from the dragon's hoard, rousing him to wrath—an incident directly mirroring Beowulf, and an action entirely determined by traditional narrative patterns. As Tolkien wrote, "The episode of the theft arose naturally (and almost inevitably) from the circumstances. It is difficult to think of any other way of conducting the story at this point. I fancy the author of Beowulf would say much the same."[14]

References

- Citations

- ↑ "JRR Tolkien's Beowulf translation to be published". BBC News. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ "Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary". Publishers Weekly. 26 May 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Acocella, Joan (2 June 2014). "Slaying Monsters: Tolkien's 'Beowulf'". The New Yorker. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- 1 2 Worrall, Patrick (22 May 2014). "Tolkien's Beowulf: a 'great gift'". Channel 4. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ "Hwæt? a new academic spat over Tolkien". London Evening Standard. 21 May 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Kiernan, Kevin (2 June 2014). "Why Tolkien Hated His Translation Of Beowulf". Business Insider. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- 1 2 Gilsdorf, Ethan (18 May 2014). "Waving His Wand at 'Beowulf'". New York Times. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, letter No. 7

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, letter No. 25

- ↑ Faraci, Mary (2002). "'I wish to speak' (Tolkien's voice in his Beowulf essay)". In Chance, Jane. Tolkien the Medievalist. Routledge. pp. 58–59. ISBN 0-415-28944-0.

- ↑ Solopova, Elizabeth (2009), Languages, Myths and History: An Introduction to the Linguistic and Literary Background of J.R.R. Tolkien's Fiction, New York City: North Landing Books, p. 37, ISBN 0-9816607-1-1

- ↑ Purtill, Richard L. (2006). Lord of the Elves and Eldils. Ignatius Press. pp. 53–55. ISBN 1-58617-084-8.

- ↑ McDonald, R. Andrew; Whetter, K. S. (2006). "'In the hilt is fame': resonances of medieval swords and sword-lore in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings". Mythlore (95/96).

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, p. 31

- Works cited

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-31555-7