Boley, Oklahoma

| Boley, Oklahoma | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

|

Boley 100th Birthday Rodeo & Bar-B-Q Festival | |

|

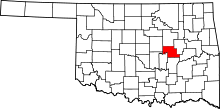

Location of Boley, Oklahoma | |

| Coordinates: 35°29′34″N 96°28′54″W / 35.49278°N 96.48167°WCoordinates: 35°29′34″N 96°28′54″W / 35.49278°N 96.48167°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oklahoma |

| County | Okfuskee |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.6 sq mi (4.3 km2) |

| • Land | 1.6 sq mi (4.3 km2) |

| • Water | 0.0 sq mi (0.0 km2) |

| Elevation | 892 ft (272 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 1,184 |

| • Density | 740.0/sq mi (275.3/km2) |

| Time zone | Central (CST) (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP code | 74829 |

| Area code(s) | 539/918 |

| FIPS code | 40-07500[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1090385[2] |

Boley is a town in Okfuskee County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 1,184 at the 2010 census, a gain of 5.2 percent from 1,126 in 2000.[3] Boley was established in 1903 as a predominantly Black pioneer town with Native American ancestry among its citizens.[4]

The Boley Public School District is one of the smallest public school districts in the state of Oklahoma. For the most recent data available, it tied with Sweetwater for the smallest high school with 15 students. For a combined district, K-12, Boley finished first, just ahead of Clarita (58) and Sweetwater (60), with 51 students.[5] Boley is also home to BBQ equipment maker, Smokaroma, Inc, and the John Lilley Correctional Center. The Boley Historic District is a National Historic Landmark.[6][7] Currently Boley hosts The Annual Boley Rodeo & Bar-B-Que Festival.[8]

History

This area was settled by Creek Freedmen, whose ancestors had been held as slaves of the Creek at the time of Indian Removal in the 1830s. After the American Civil War, the United States negotiated new treaties with tribes that allied with the Confederacy. It required them to emancipate their slaves and give them membership in the tribes. Those formerly slaves were called the Creek Freedmen. At the time of allotments to individual households under the Dawes Commission, Creek Freedmen were registered as such on the Dawes Rolls (even if they were of mixed-race and also descended directly from Creek ancestors.) Creek Freedmen set up independent townships, of which Boley was one. The town was established on the land allotted to Abigail Barnett, daughter of James Barnett, a Creek freedman.[9]

The coming of the Fort Smith & Western Railroad allowed agricultural land to be more profitably used as a townsite. Property owned by the Barnett family, among other Creek Freedmen, was midway between Paden and Castle, and ideal for a station stop. With the approval of the railroad management, Boley, Creek Nation, Indian Territory was incorporated in 1905. It was named for J. B. Boley, an official of the railroad.[9] There were no other African-American towns nearby, it became a center of regional business. During the early part of the 20th century, Boley was one of the wealthiest Negro towns in the US. It boasted the first nationally chartered bank owned by blacks, and its own electric company.[10] The town had over 4,000 residents by 1911, and was the home of two colleges: Creek-Seminole College, and Methodist Episcopal College. The Masonic Lodge was called "the tallest building between Okmulgee and Oklahoma City," when it was built in 1912.[9] Booker T. Washington visited Boley in 1905, and was so impressed that he included Boley in his speeches.

Boley's development paralleled that of the railroad. After World War I, a fall in agricultural prices and the bankruptcy of the railroad caused Boley's failure. It went bankrupt in 1939 during the Great Depression. Before World War II, Boley's population had declined to about 700.[9] With the Second Great Migration underway, by 1960 most of the population had left for other urban areas.[11][12] So far the New Great Migration has not benefited Boley.

Timeline

- 1903 Founding[9]

- 1905 Booker T. Washington tours the newly incorporated Boley. Newspaper The Boley Progress starts publication.[13]

- 1907 Oklahoma becomes a state. Although by 1897 Oklahoma law required black children to be educated separately from white children, with statehood the legislature passed Jim Crow laws similar to those in much of the South. Oklahoma was no longer a refuge for colored people from Jim Crow.[14]

- 1911 Facts about Boley, Okla. the largest and wealthiest exclusive Negro city in the world. (Boley, OK: Commercial Club, 1911[15]

- 1922 "Produced in the All-Colored City of Boley, Okla." The Crimson Skull; Baffling Western Mystery Photo-Play, starring Bill Pickett, was an example of the race movie genre.[16]

- 1925, State Training School for Incorrigible Negro Boys was located in Boley; it would become the John Lilley Correctional Center.

- 1926 The Boley Progress ceases publication.

- 1932 Armed citizens of Boley thwart a bank robbery attempt by members of Pretty Boy Floyd's gang.[17]

- 1934 30th Anniversary Celebration[18]

- 1939 Fort Smith & Western Railroad and Boley go bankrupt.

- 1959 Smokaroma founded.

- 1961 First of the Annual Boley Rodeo & Bar-B-Que Festivals.

- 1975 Boley National Historic District given landmark status.

Inscription on Oklahoma Historical Society plaque honoring Boley

Boley, Oklahoma Est. August 1903 - Inc. May 1905 Boley, Creek Nation, I.T., Established as all black town on land of Creek Indian Freedwoman Abigail Barnett. Organized by T.M. Haynes first townsite manager. Named for J.B. Boley, white roadmaster, who convinced Fort Smith & Western Railroad that blacks could govern themselves. This concept soon boosted population to 4,200. Declared National Historic Landmark District by Congress 5-15-1975. Oklahoma Historical Society [19]

Boley Historic District

Part of Boley was declared as Boley Historic District and a National Historic Landmark in 1975. The District is roughly bounded by Seward Avenue, Walnut and Cedar Streets, and the southern city limits of Boley.[20][21]

Quotations about Boley from Booker T. Washington

"They have recovered something of the knack for trade that their fore-parents in Africa were famous for".[11]

"Boley, Indian Territory, is the youngest, most enterprising, and in many ways the most interesting of the Negro towns in the US."[22]

Notable people

- Cardell Camper, major league baseball player

- Pumpsie Green - baseball player, first African American to play for the Boston Red Sox

- Zenobia Powell Perry - composer[23]

Geography

Boley is located at 35°29′34″N 96°28′54″W / 35.49278°N 96.48167°W (35.492813, -96.481776).[24] The cemetery is located southwest of the town.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 1.6 square miles (4.1 km2), all land.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 1,334 | — | |

| 1920 | 1,154 | −13.5% | |

| 1930 | 874 | −24.3% | |

| 1940 | 942 | 7.8% | |

| 1950 | 646 | −31.4% | |

| 1960 | 573 | −11.3% | |

| 1970 | 514 | −10.3% | |

| 1980 | 423 | −17.7% | |

| 1990 | 908 | 114.7% | |

| 2000 | 1,126 | 24.0% | |

| 2010 | 1,184 | 5.2% | |

| Est. 2015 | 1,183 | [25] | −0.1% |

As of the census[1] of 2000, there were 1,126 people, 136 households, and 79 families residing in the town. The population density was 684.6 people per square mile (265.1/km²). There were 153 housing units at an average density of 93.0 per square mile (36.0/km²). The racial makeup of the town was 35.61% White, 54.71% African American, 4.97% Native American, 0.09% Asian, 1.51% from other races, and 3.11% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.11% of the population.

There were 136 households out of which 18.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 33.8% were married couples living together, 19.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.9% were non-families. 36.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 19.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 3.10.

In the town the population was spread out with 7.6% under the age of 18, 9.1% from 18 to 24, 51.0% from 25 to 44, 24.5% from 45 to 64, and 7.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females there were 407.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 490.9 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $16,042, and the median income for a family was $27,500. Males had a median income of $21,875 versus $20,625 for females. The per capita income for the town was $9,304. About 25.0% of families and 40.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 48.5% of those under age 18 and 20.3% of those age 65 or over.

See also

- Boley Historic District

- Brooksville, Clearview, Grayson, Langston, Lima, Red Bird, Rentiesville, Summit, Taft, Tatums, Tullahassee, and Vernon, other "All-Black" settlements that were part of the Land Run of 1889.[27]

References

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ Oklahoma Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- ↑ (Decatur-Thomas, 1989)

- ↑ School District Database at the Oklahoma State Department of Education (OSDE)

- ↑ National Park Service Archived May 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Preservation Oklahoma - Boley Historic District Archived July 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Boley Rodeo

- 1 2 3 4 5 O'Dell, Larry. "Boley." Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Archived March 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- ↑ Boley, Oklahoma, C. Sharp & Associates Inc., 2000 Archived April 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Booker T. Washington and the adult education movement By Virginia Lantz Denton

- ↑ Integration Or Separation? By Roy Lavon Brooks (including a short history of Boley)

- ↑ Boley Progress, Library of Congress

- ↑ Jim Crow Laws: Oklahoma Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Facts about Boley, Okla. - Open Library

- ↑ The Crimson Skull

- ↑ Boley's bank robbed!

- ↑ Text of Souvenir Program of Boley's 30th Anniversary Celebration

- ↑ Town Plaque

- ↑ "Boley Historic District". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ↑ Marcia M. Greenlee (September 27, 1974). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Boley, Oklahoma Historic District / Boley Historic District" (pdf). National Park Service. and Accompanying 16 photos from 1974. (6.67 MB)

- ↑ Booker T. Washington papers, V.9 1906-1908 Archived January 17, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Zenobia Powell Perry, An American Composer By Jeannie Gayle Pool, IAWM Journal (2003) Archived October 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ O'Dell, Larry. "All-Black Towns". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

Decatur-Thomas, C. (1989) Boley: An all black pioneer town and the education of its children. [Dissertation] The University of Akron

External links

- History of Boley on The African American Registry

- Black heritage sites, Boley Historic District, By Nancy C. Curtis

- Oklahoma Historical Society, Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture, Boley

- Boley cemetery index from rootsweb

- History of Boley published 1945 from rootsweb

- NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM including a history and inventory of historic buildings

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Boley

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - All-Black Towns

Decatur-Thomas, C. (1989) Boley: An all black pioneer town and the education of its children. [Dissertation] The University of Akron