Brontosaurus

| Brontosaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic, 155–152 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

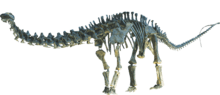

| Holotype specimen of B. excelsus (YPM 1980), Peabody Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Neosauropoda |

| Family: | †Diplodocidae |

| Subfamily: | †Apatosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Brontosaurus Marsh, 1879 |

| Type species | |

| †Brontosaurus excelsus Marsh, 1879 | |

| Referred Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Brontosaurus (/ˌbrɒntəˈsɔːrəs/[1][2] bron-tə-SAWR-əs), meaning "thunder lizard" (from Greek βροντή, brontē = thunder + σαυρος, sauros = lizard), is a genus of sauropod dinosaurs. Originally named by its discoverer Othniel Charles Marsh in 1879, Brontosaurus had long been considered a junior synonym of Apatosaurus; its original species Brontosaurus excelsus was reclassified as A. excelsus in 1903. However, an extensive study published in 2015 by a joint British-Portuguese research team concluded that Brontosaurus was a valid genus of sauropod distinct from Apatosaurus.[3][4][5] Nevertheless, not all paleontologists agree with this division.[6][7]

The same study classified two additional species that had once been considered Apatosaurus and Eobrontosaurus as Brontosaurus parvus and Brontosaurus yahnahpin respectively.[3] Species of Brontosaurus range in age from 155 to 152 million years ago, during the Kimmeridgian age of the lower to middle Morrison Formation in Wyoming and Utah, United States.[8]

As the archetypal sauropod, Brontosaurus is one of the best-known dinosaurs, and has been featured in film, advertising, and postal stamps, as well as many other types of media.

Description

Brontosaurus was a large, long-necked quadrupedal animal with a long, whip-like tail, and forelimbs that were slightly shorter than their hindlimbs. The largest species, B. excelsus, weighed up to 15 tonnes (15 long tons; 17 short tons) and measured up to 22 m (72 ft) long from head to tail.[9]

The skull of Brontosaurus has not been found, but was probably similar to the skull of the closely related Apatosaurus. Like those of other sauropods, the vertebrae of the neck were deeply bifurcated; that is, they carried paired spines, resulting in a wide and deep neck.[10] The vertebral formula was: 15 cervicals, 10 dorsals, five sacrals, and 82 caudals. The caudal vertebra number was noted to vary, even within a species. The cervical vertebrae were stouter than other diplodocids, though not as stout as in mature specimens of Apatosaurus. The dorsal ribs are not fused or tightly attached to their vertebrae, instead being loosely articulated.[11] Ten dorsal ribs are on either side of the body.[12] The large neck was filled with an extensive system of weight-saving air sacs. Brontosaurus, like its close relative Apatosaurus, had tall spines on its vertebrae, which make up more than half the height of the individual bones. The shape of the tail was unusual for diplodocids, being comparatively slender, due to the vertebral spines rapidly decreasing in height the farther they are from the hips. Brontosaurus also had very long ribs compared to most other diplodocids, giving them unusually deep chests.[13] As in other diplodocids, the last portion of the tail of Brontosaurus possessed a whip-like structure.[11]

The limb bones were also very robust.[13] The arm bones are stout, with the humerus resembling that of Camarasaurus, and those of B. excelsus being nearly identical to those of Apatosaurus ajax. Charles Gilmore in 1936 noted that previous reconstructions erroneously proposed that the radius and ulna could cross, when in life they would have remained parallel.[11] Brontosaurus had a single large claw on each forelimb, and the first three toes possessed claws on each foot.[14] Even by 1936, it was recognized that no sauropod had more than one hand claw preserved, and this one claw is now accepted as the maximum number throughout the entire group.[11][15] The single front claw bone is slightly curved, and squarely shortened on the front end. The hip bones included robust ilia, and the fused pubes and ischia. The tibia and fibula bones of the lower leg were different from the slender bones of Diplodocus, but nearly indistinguishable from those of Camarasaurus. The fibula is longer than the tibia, although it is also more slender.[11]

Classification

Brontosaurus is a member of the family Diplodocidae, a clade of gigantic sauropod dinosaurs. The family includes some of the longest and largest creatures ever to walk the earth, including Diplodocus, Supersaurus, and Barosaurus. Brontosaurus is also classified in the subfamily Apatosaurinae, which also includes Apatosaurus and one or more possible unnamed genera.[3] Othniel Charles Marsh described Brontosaurus as being allied to Atlantosaurus, within the now defunct group Atlantosauridae.[12][16] In 1878, Marsh raised his family to the rank of suborder, including Apatosaurus, Brontosaurus, Atlantosaurus, Morosaurus (=Camarasaurus), and Diplodocus. He classified this group within Sauropoda. In 1903, Elmer S. Riggs mentioned that the name Sauropoda would be a junior synonym of earlier names, and grouped Apatosaurus within Opisthocoelia.[12] Most authors still use Sauropoda as the group name. [17]

Cladogram of the Diplodocidae after Tschopp, Mateus, and Benson (2015):[3]

| Diplodocidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Species

- Brontosaurus excelsus, the type species of Brontosaurus, was first named by Marsh in 1879. Many specimens, including the holotype specimen YPM 1980, have been assigned to the species. They include FMNH P25112, the skeleton mounted at the Field Museum of Natural History, which has since been found to represent an unknown species of apatosaurine. Brontosaurus amplus, occasionally assigned to B. parvus, is a junior synonym of B. excelsus. B. excelsus therefore only includes its type specimen and the type specimen of B. amplus.[3][17] The largest of these specimens is estimated to have weighed up to 15 tonnes and measured up to 22 m (72 ft) long from head to tail.[9] Both known definitive B. excelsus fossils have been reported from Reed’s Quarry 10 of the Morrison Formation Brushy Basin member in Albany County, Wyoming, dated to the late Kimmeridgian age,[3] about 152 million years ago.

- Brontosaurus parvus, first described as Elosaurus in 1902 by Peterson and Gilmore, was reassigned to Apatosaurus in 1994, and to Brontosaurus in 2015. Specimens assigned to this species include the holotype, CM 566 (a partial skeleton of a juvenile found in Sheep Creek Quarry 4 in Albany County, WY), BYU 1252-18531 (a nearly complete skeleton found in Utah and mounted at Brigham Young University), and the partial skeleton UW 15556 (which had once been accidentally mixed together with the holotype). It dates to the middle Kimmeridgian.[17] Adult specimens are estimated to have weighed up to 14 tonnes and measured up to 22 m (72 ft) long from head to tail.[9]

- Brontosaurus yahnahpin is the oldest species, known from a single site from the lower Morrison Formation, Bertha Quarry, in Albany County, Wyoming, dating to about 155 million years ago.[8][18] It grew up to 21 metres (69 ft) long.[19] The type species, E. yahnahpin, was described by James Filla and Patrick Redman in 1994 as a species of Apatosaurus (A. yahnahpin).[20] The specific name is derived from Lakota mah-koo yah-nah-pin, "breast necklace", a reference to the pairs of sternal ribs that resemble the hair pipes traditionally worn by the tribe. The holotype specimen is TATE-001, a relatively complete postcranial skeleton found in Wyoming, in the lower Morrison Formation. More fragmentary remains have also been referred to the species. A re-evaluation by Robert T. Bakker in 1998 found it to be more primitive, so Bakker coined the new generic name Eobrontosaurus, derived from Greek eos, "dawn", and Brontosaurus.[21]

The cladogram below is the result of an analysis by Tschopp, Mateus, and Benson (2015). The authors analyzed most diplodocid type specimens separately to deduce which specimen belonged to which species and genus.[3]

| Apatosaurinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

History

In 1879, O.C. Marsh, a professor of paleontology at Yale University, announced the discovery of a large and fairly complete sauropod skeleton from Morrison Formation rocks at Como Bluff, Wyoming. He identified it as belonging to an entirely new genus and species, which he named Brontosaurus excelsus,[12] [22] meaning "thunder lizard", from the Greek brontē/βροντη meaning "thunder" and sauros/σαυρος meaning "lizard",[23] and from the Latin excelsus, "noble" or "high".[24] By this time, the Morrison Formation had become the center of the Bone Wars, a fossil-collecting rivalry between early paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope. Because of this, the publications and descriptions of taxa by Marsh and Cope were rushed at the time.[25]

Elmer Riggs, in the 1903 edition of Geological Series of the Field Columbian Museum, argued that Brontosaurus was not different enough from Apatosaurus to warrant its own genus, so he created the new combination Apatosaurus excelsus for it. Riggs stated that "In view of these facts the two genera may be regarded as synonymous. As the term 'Apatosaurus' has priority, 'Brontosaurus' will be regarded as a synonym".[12] Nonetheless, before the mounting of the American Museum of Natural History specimen, Henry Fairfield Osborn chose to label the skeleton "Brontosaurus", though he was a strong opponent of Marsh and his taxa.[26][27]

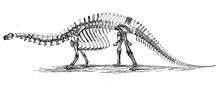

In 1905, the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) unveiled the first-ever mounted skeleton of a sauropod, a composite specimen (mainly made of bones from AMNH 460) that they referred to as the species Brontosaurus excelsus. The AMNH specimen was very complete, only missing the feet (feet from the specimen AMNH 592 were added to the mount), lower leg, and shoulder bones (added from AMNH 222), and tail bones (added from AMNH 339).[28] To complete the mount, the rest of the tail was fashioned to appear as Marsh believed it should, which had too few vertebrae. In addition, a sculpted model of what the museum felt the skull of this massive creature might look like was placed on the skeleton. This was not a delicate skull like that of Diplodocus, which would later turn out to be more accurate, but was based on "the biggest, thickest, strongest skull bones, lower jaws and tooth crowns from three different quarries".[11][12][29][30] These skulls were likely those of Camarasaurus, the only other sauropod for which good skull material was known at the time. The mount construction was overseen by Adam Hermann, who failed to find Brontosaurus skulls. Hermann was forced to sculpt a stand-in skull by hand. Henry Fairfield Osborn noted in a publication that the skull was "largely conjectural and based on that of Morosaurus" (now Camarasaurus).[26]

In 1909, an Apatosaurus skull was found, during the first expedition to what would become the Carnegie Quarry at Dinosaur National Monument, led by Earl Douglass. The skull was found a few meters away from a skeleton (specimen CM 3018) identified as the new species Apatosaurus louisae. The skull was designated CM 11162, and was very similar to the skull of Diplodocus. It was accepted as belonging to the Apatosaurus specimen by Douglass and Carnegie Museum director William H. Holland, although other scientists, most notably Osborn, rejected this identification. Holland defended his view in 1914 in an address to the Paleontological Society of America, yet he left the Carnegie Museum mount headless. While some thought Holland was attempting to avoid conflict with Osborn, others suspected that Holland was waiting until an articulated skull and neck were found to confirm the association of the skull and skeleton.[26] After Holland's death in 1934, a cast of a Camarasaurus skull was placed on the mount by museum staff.[27]

At the Yale Peabody Museum, a skeleton was mounted in 1931 with a skull unique from all the others. While at the time most museums were using Camarasaurus casts, the Peabody Museum sculpted a completely different skull. They based the lower jaw on a Camarasaurus mandible, with the cranium resembling Marsh's 1891 illustration. The skull also included forward-pointing nasals, something truly different to any dinosaur, and fenestrae differing from the drawing and other skulls.[26]

No apatosaurine skull was mentioned in literature until the 1970s, when John Stanton McIntosh and David Berman redescribed the skulls of Diplodocus and Apatosaurus. They found that though he never published his opinion, Holland was almost certainly correct, that Apatosaurus (and Brontosaurus) had a Diplodocus-like skull. According to them, many skulls long thought to pertain to Diplodocus might instead be those of Apatosaurus. They reassigned multiple skulls to Apatosaurus based on associated and closely associated vertebrae. Though they supported Holland, Apatosaurus was noted to possibly have possessed a Camarasaurus-like skull, based on a disarticulated Camarasaurus-like tooth found at the precise site where an Apatosaurus specimen was found years before.[30] On October 20, 1979, after the publications by McIntosh and Berman, the first skull of an Apatosaurus was mounted on a skeleton in a museum, that of the Carnegie.[27] In 1995, the American Museum of Natural History followed suit, and unveiled their remounted skeleton (now labelled Apatosaurus excelsus) with a corrected tail and a new skull cast from A. louisae.[28] In 1998, the Felch Quarry skull that Marsh included in his 1896 skeletal restoration was suggested to belong to Brachiosaurus instead.[31] In 2011, the first specimen of Apatosaurus where a skull was found articulated with its cervical vertebrae was described. This specimen, CMC VP 7180, was found to differ in both skull and neck features from A. louisae, and the specimen was found to have a majority of features related to those of A. ajax.[32]

Almost all 20th-century paleontologists agreed with Riggs that all Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus species should be classified together in a single genus. According to the rules of the ICZN (which governs the scientific names of animals), the name Apatosaurus, having been published first, had priority as the official name; Brontosaurus was considered a junior synonym and was therefore discarded from formal use.[33][34][35][36] Despite this, at least one paleontologist—Robert T. Bakker—argued in the 1990s that A. ajax and A. excelsus are in fact sufficiently distinct that the latter continues to merit a separate genus.[37] In 2015, an extensive study of diplodocid relationships by Emanuel Tschopp, Octavio Mateus, and Roger Benson concluded that Brontosaurus was indeed a valid genus of sauropod distinct from Apatosaurus. The scientists developed a statistical method to more objectively assess differences between fossil genera and species, and concluded that Brontosaurus could be "resurrected" as a valid name. They assigned two former Apatosaurus species, A. parvus and A. yahnahpin, to Brontosaurus, as well as the type species B. excelsus.[3] Paleontologist Michael D'Emic made a critique.[6] Palaeontologist Donald Prothero criticized the mass media reaction to this study as superficial and premature, concluding:

Until someone has convincingly addressed the issue, I’m going to put “Brontosaurus” in quotes and not follow the latest media fad, nor will I overrule Riggs (1903) and put the name in my books as a valid genus.[7]

Palaeobiology

Posture and locomotion

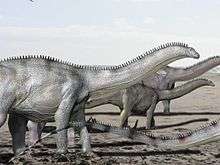

Historically, sauropods like Brontosaurus were believed to be too massive to support their own weight on dry land, so theoretically they must have lived partly submerged in water, perhaps in swamps. Recent findings do not support this, and sauropods are thought to have been fully terrestrial animals.[38]

Diplodocids like Brontosaurus are often portrayed with their necks held high up in the air, allowing them to browse on tall trees. Though some studies have suggested that diplodocid necks were less flexible than previously believed,[39] other studies have found that all tetrapods appear to hold their necks at the maximum possible vertical extension when in a normal, alert posture, and argue that the same would hold true for sauropods barring any unknown, unique characteristics that set the soft tissue anatomy of their necks apart from that of other animals.[40]

Trackways of sauropods like Brontosaurus show that the average range for them was around 20–40 km (12–25 mi) per day, and they could potentially reach a top speed of 20–30 km (12–19 mi) per hour.[10] The slow locomotion of sauropods may be due to the minimal muscling or recoil after strides.[41]

Various uses have been proposed for the single claw on the forelimb of sauropods. They were suggested to have been for defence, but the shape and size of them makes this unlikely. Other predictions were that it could be for feeding, but the most probable is that the claw was for grasping objects like tree trunks when rearing.[15]

Physiology

James Spotila et al. (1991) suggest that the large body size of Brontosaurus and other sauropods would have made them unable to maintain high metabolic rates, as they would not be able to release enough heat. However, temperatures in the Jurassic were 3 degrees Celsius higher than present. [42] They assumed that the animals had a reptilian respiratory system. Wedel found that an avian system would have allowed them to dump more heat.[43] Some scientists have argued that the heart would have had trouble sustaining sufficient blood pressure to oxygenate the brain.[38]

Juveniles

.jpg)

Juvenile Brontosaurus material is known based on the type specimen of B. parvus. The material of this specimen, CM 566, includes vertebrae from various regions, one pelvic bone, and some bones of the hind limb.[17]

Tail

An article that appeared in the November 1997 issue of Discover Magazine reported research into the mechanics of diplodocid tails by Nathan Myhrvold, a computer scientist from Microsoft. Myhrvold carried out a computer simulation of the tail, which in diplodocids like Brontosaurus was a very long, tapering structure resembling a bullwhip. This computer modeling suggested that sauropods were capable of producing a whip-like cracking sound of over 200 decibels, comparable to the volume of a cannon.[44]

Paleoecology

The Morrison Formation is a sequence of shallow marine and alluvial sediments which, according to radiometric dating, ranges between 156.3 million years old (Mya) at its base,[45] and 146.8 Mya at the top,[46] which places it in the late Oxfordian, Kimmeridgian, and early Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic period. This formation is interpreted as a semiarid environment with distinct wet and dry seasons. The Morrison Basin, where dinosaurs lived, stretched from New Mexico to Alberta and Saskatchewan, and was formed when the precursors to the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains started pushing up to the west. The deposits from their east-facing drainage basins were carried by streams and rivers and deposited in swampy lowlands, lakes, river channels, and floodplains.[47] This formation is similar in age to the Lourinha Formation in Portugal and the Tendaguru Formation in Tanzania.[48]

Brontosaurus may have been a more solitary animal than other Morrison Formation dinosaurs.[49] As a genus, Brontosaurus existed for a long span of time, and have been found in most levels of the Morrison. B. excelsus fossils have been reported from the upper Salt Wash Member to the upper Brushy Basin Member, ranging from the middle to late Kimmeridgian age, about 154–151 Mya. Additional remains are known from even younger rocks, but they have not been identified as any particular species.[18] Older Brontosaurus remains have also been identified from the middle Kimmeridgian, and are assigned to B. parvus.[17] Fossils of these animals have been found in Nine Mile Quarry and Bone Cabin Quarry in Wyoming and at sites in Colorado, Oklahoma, and Utah, present in stratigraphic zones 2–6.[50]

The Morrison Formation records an environment and time dominated by gigantic sauropod dinosaurs.[50] Dinosaurs known from the Morrison include the theropods Ceratosaurus, Ornitholestes, and Torvosaurus, the sauropods Apatosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Diplodocus, and the ornithischians Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, and Stegosaurus.[51] Allosaurus accounted for 70 to 75% of theropod specimens and was at the top trophic level of the Morrison food web.[52] Other vertebrates that shared this paleoenvironment included ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, turtles, sphenodonts, lizards, terrestrial and aquatic crocodylomorphans, and several species of pterosaurs. Shells of bivalves and aquatic snails are also common. The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of green algae, fungi, mosses, horsetails, cycads, ginkgoes, and several families of conifers. Vegetation varied from river-lining forests of tree ferns, and ferns (gallery forests), to fern savannas with occasional trees such as the Araucaria-like conifer Brachyphyllum.[53]

In popular culture

The length of time taken for Riggs' 1903 reclassification of Brontosaurus as Apatosaurus to be brought to public notice, as well as Osborn's insistence that the Brontosaurus name be retained despite Riggs' paper, meant that the Brontosaurus became one of the most famous dinosaurs. In fact, "Brontosaurus" often appears as a synonym for Dinosaur itself. Brontosaurus have often been depicted in cinema, beginning with Winsor McCay's 1914 classic Gertie the Dinosaur, one of the first animated films.[54] McCay based his unidentified dinosaur on the apatosaurine skeleton in the American Museum of Natural History.[55] The 1925 silent film The Lost World featured a battle between a Brontosaurus and an Allosaurus, using special effects by Willis O'Brien.[56] The Brontosaurus is the main plot focus of the 1985 movie Baby: Secret of the Lost Legend, in which a family of Brontosaurs are found still living in Africa.[57][58] These, and other early uses of the animal as major representative of the group, helped cement Brontosaurus as a quintessential dinosaur in the public consciousness.[59]

Sinclair Oil Corporation has long been a fixture of American roads (and briefly in other countries) with its green dinosaur logo and mascot, a Brontosaurus. While Sinclair's early advertising included a number of different dinosaurs, eventually only Brontosaurus was used as the official logo, due to its popular appeal.[60]

Gertie_the_Dinosaur.webm.jpg)

As late as 1989, the U.S. Postal Service caused controversy when it issued four "dinosaur" stamps: Tyrannosaurus, Stegosaurus, Pteranodon, and Brontosaurus. The use of the term Brontosaurus in place of Apatosaurus led to complaints of "fostering scientific illiteracy."[61] The Postal Service defended itself (in Postal Bulletin 21744) by saying, "Although now recognized by the scientific community as Apatosaurus, the name 'Brontosaurus' was used for the stamp because it is more familiar to the general population." Indeed, the Postal Service even implicitly rebuked the somewhat inconsistent complaints by adding that "[s]imilarly, the term 'dinosaur' has been used generically to describe all the animals [i.e., all four of the animals represented in the given stamp set], even though the Pteranodon was a flying reptile [rather than a true 'dinosaur']," a distinction left unmentioned in the numerous correspondence regarding the Brontosaurus/Apatosaurus issue. Palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould not only supported this position, but indeed, cheered and advanced it enough to not only name an essay, but even the entire book of which it is but a part "Bully for Brontosaurus", stating: "Touché and right on; no one bitched about Pteranodon, and that's a real error."[59] His position, however, was not one suggesting the exclusive use of the popular moniker; he echoed Riggs' original argument that Brontosaurus is a synonym for Apatosaurus. Nevertheless, he noted that the former has developed and continues to maintain an independent existence in the popular imagination.[59]

The more vociferous denunciations of the usage have elicited sharply defensive statements from those who would not wish to see the name be struck from official usage.[59] Tschopp's study[3] has generated a very high number of responses from many, often opposed, groups - of editorial,[62] news staff,[4][63] and personal blog nature (both related[64][65] and not[66]), from both[67] sides of the debate, from related[68] and unrelated contexts, and from all over the world.[69]

References

- ↑ "Brontosaurus". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ↑ "Brontosaurus". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Tschopp, E.; Mateus, O. V.; Benson, R. B. J. (2015). "A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda)". PeerJ. 3: e857. doi:10.7717/peerj.857. PMC 4393826

. PMID 25870766.

. PMID 25870766.

- 1 2 Gorman, James (7 April 2015). "A Prehistoric Giant Is Revived, if Only in Name". New York Times. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ ScientificAmerican.com The Brontosaurus is Back 2015-4-07

- 1 2 D'Emic, M. 2015. "Not so fast, Brontosaurus". Time.com

- 1 2 Prothero, D. 2015. "Is "Brontosaurus" Back? Not So Fast!". Skeptic.com.

- 1 2 Foster, J. (2007). Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. 389pp.

- 1 2 3 Paul, Gregory S. (2010). Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- 1 2 Fastovsky, D.E.; Weishampel, D.B. (2009). Dinosaurs: A Concise Natural History (PDF). Cambridge University Press. pp. 165–200. ISBN 978-0-521-88996-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gilmore, C.W. (February 1936). "Osteology of Apatosaurus, with special references to specimens in the Carnegie Museum". Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum. 11 (4): 1–136. OCLC 16777126.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Riggs, E.S. (August 1903). "Structure and Relationships of Opisthocoelian Dinosaurs. Part I, Apatosaurus Marsh" (PDF). Publications of the Field Columbian Museum Geographical Series. 2 (4): 165–196. OCLC 494478078.

- 1 2 Lovelace, D.M.; Hartman, S.A.; Wahl, W.R. (2007). "Morphology of a specimen of Supersaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, and a re-evaluation of diplodocid phylogeny". Arquivos do Museu Nacional. 65 (4): 527–544. ISSN 0365-4508.

- ↑ Martin, A.J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs (Second ed.). Blackwell Publishing. p. 560. ISBN 1-4051-3413-5. ASIN 1405134135.

- 1 2 Upchurch, P. (1994). "Manus claw function in sauropod dinosaurs" (PDF). Gaia. 10: 161–171. ISSN 0871-5424.

- ↑ Marsh, O.C. (December 1877). "Notice of New Dinosaurian Reptiles from the Jurassic formation" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 14 (84): 514–516.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Upchurch, P.; Tomida, Y.; Barrett, P.M. (2005). "A new specimen of Apatosaurus ajax (Sauropoda: Diplodocidae) from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Wyoming, USA". National Science Museum monographs. 26 (118): 1–156. ISSN 1342-9574.

- 1 2 Turner, C.E. and Peterson, F., (1999). "Biostratigraphy of dinosaurs in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of the Western Interior, U.S.A." Pp. 77–114 in Gillette, D.D. (ed.), Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 99-1.

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2010 Appendix.

- ↑ Filla, J.A., Redman, P.D. (1994). "Apatosaurus yahnahpin: a preliminary description of a new species of diplodocid dinosaur from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation (Kimmeridgian-Portlandian) and Cloverly Formation (Aptian-Albian) of the western United States", Mémoires de la Société Géologique de France (Nouvelle Série) 139 (Ecosystèmes Continentaux du Mésozoique): 87-93

- ↑ Bakker, R.T. (1998). "Dinosaur mid-life crisis: the Jurassic-Cretaceous transition in Wyoming and Colorado". In: S.G. Lucas, J.I. Kirkland, & J.W. Estep (eds.) Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems; New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 14: 67–77.

- ↑ Marsh, O.C. (1979). "Notice of new Jurassic dinosaurs" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 18: 501–505.

- ↑ Liddell, G.H.; Scott, R. (1882). A Greek-English Lexicon. Harper & Brothers. pp. 1–1774.

- ↑ Mahoney, K.D. (2015). "Latin Definitions for: excelsus (Latin search)". LatDict Latin Dictionary and Grammar Resources.

- ↑ Moon, B. (2010). "The Sauropod Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic, USA): A Review". Dinosauria: 1–9.

- 1 2 3 4 Miller, B. (2014-10-30). "Bully for Camarasaurus". Dinosours.

- 1 2 3 Parsons, K.M. (1997). "The Wrongheaded Dinosaur". Carnegie Magazine.

- 1 2 Norell, M.A., Gaffney, E.S., & Dingus, L. (1995). Discovering Dinosaurs in the American Museum of Natural History. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- ↑ Bakker, R.T. (1994). "The Bite of the Bronto". Earth. 3 (6): 26–33.

- 1 2 McIntosh, J.S.; Berman, D.S. (1975). "Description of the Palate and Lower Jaw of the Sauropod Dinosaur Diplodocus (Reptilia: Saurischia) with Remarks on the Nature of the Skull of Apatosaurus". Journal of Paleontology. 49 (1): 187–199. JSTOR 1303324.

- ↑ Carpenter, Kenneth; Tidwell, Virginia (1998). "Preliminary Description of a Brachiosaurus Skull from Felch Quarry 1, Garden Park, Colorado". In Carpenter, Kenneth; Chure, Dan; Kirkland, James Ian. The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: an interdisciplinary study. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-90-5699-183-8.

- ↑ Barrett, P.M.; Storrs, G.W.; Young, M.T.; Witmer, L.M. (2011). "A new skull of Apatosaurus and its taxonomic and palaeobiological implications" (PDF). Symposium of Vertebrate Palaeontology & Comparative Anatomy Abstracts of Presentations: 5.

- ↑ Taylor, M.P. (2010). "Sauropod dinosaur research: a historical review" (PDF). Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 343 (1): 361–386. Bibcode:2010GSLSP.343..361T. doi:10.1144/SP343.22.

- ↑ Brinkman, P. (2006). "Bully for Apatosaurus". Endeavour. 30 (4): 126–130. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2006.10.004. PMID 17097734.

- ↑ Upchurch, P.; Barrett, P.M.; Dodson, P. (2004). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel, D.B.; Osmólska, H.; Dodson, P. The Dinosauria (2 ed.). University of California Press. pp. 259–322.

- ↑ McIntosh, J.S. (1995). A. Sun; Y. Wang, eds. "Remarks on the North American sauropod Apatosaurus Marsh". Sixth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biota Short Papers. China Ocean Press: 119–123.

- ↑ Bakker, R.T. (1998). "Dinosaur mid-life crisis: the Jurassic-Cretaceous transition in Wyoming and Colorado". In Lucas, Spencer G.; Kirkland, James I.; Estep, J.W. Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. 14. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. pp. 67–77.

- 1 2 Pierson, D.J. (2009). "The Physiology of Dinosaurs: Circulatory and Respiratory Function in the Largest Animals Ever to Walk the Earth". Respiratory Care. 54 (7): 887–911. doi:10.4187/002013209793800286. PMID 19558740.

- ↑ Stevens, Kent A.; Parrish, JM (1999). "Neck Posture and Feeding Habits of Two Jurassic Sauropod Dinosaurs". Science. 284 (5415): 798–800. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..798S. doi:10.1126/science.284.5415.798. PMID 10221910. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ↑ Taylor, M. P. (2014). "Quantifying the effect of intervertebral cartilage on neutral posture in the necks of sauropod dinosaurs". PeerJ. 2: e712. doi:10.7717/peerj.712.

- ↑ Sellers, W.I.; Margetts, L.; Coria, R.A.; Manning, P.L. (2012). "March of the Titans: The Locomotor Capabilities of Sauropod Dinosaurs". PLoS ONE. 8 (10): e78733. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...878733S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078733. PMC 3864407

. PMID 24348896.

. PMID 24348896. - ↑ Spotila, J. R.; O'Connor, M. P.; Dodson, P. R.; Paladino, F. V. (1991). "Hot and cold running dinosaurs. Metabolism, body temperature, and migration". Modern Geology. 16: 203–227.

- ↑ Wedel, M. J. (2003). "Vertebral Pneumaticity, Air Sacs, and the Physiology of Sauropod Dinosaurs". Paleobiology. 29 (2): 243–255. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2003)029<0243:vpasat>2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4096832.

- ↑ Zimmer, C. (1 November 1997). DISCOVER Magazine "Dinosaurs in Motion" Check

|url=value (help). Discover. Retrieved 27 July 2008. - ↑ Trujillo, K.C.; Chamberlain, K.R.; Strickland, A. (2006). "Oxfordian U/Pb ages from SHRIMP analysis for the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of southeastern Wyoming with implications for biostratigraphic correlations". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 38 (6): 7.

- ↑ Bilbey, S.A. (1998). "Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry - age, stratigraphy and depositional environments". In Carpenter, K.; Chure, D.; Kirkland, J.I. The Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22. Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 87–120. ISSN 0026-7775.

- ↑ Russell, Dale A. (1989). An Odyssey in Time: Dinosaurs of North America. Minocqua, Wisconsin: NorthWord Press. pp. 64–70. ISBN 978-1-55971-038-1.

- ↑ Mateus, Octávio (2006). "Jurassic dinosaurs from the Morrison Formation (USA), the Lourinhã and Alcobaça Formations (Portugal), and the Tendaguru Beds (Tanzania): A comparison". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 223–231.

- ↑ Dodson, Peter; Behrensmeyer, A.K.; Bakker, Robert T.; McIntosh, John S. (1980). "Taphonomy and paleoecology of the dinosaur beds of the Jurassic Morrison Formation". Paleobiology. 6 (2): 208–232.

- 1 2 Foster, John (2007). Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 273–329. ISBN 978-0-253-34870-8.

- ↑ Chure, Daniel J.; Litwin, Ron; Hasiotis, Stephen T.; Evanoff, Emmett; Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "The fauna and flora of the Morrison Formation: 2006". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 233–248.

- ↑ Foster, John R. (2003). Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 23. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. p. 29.

- ↑ Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

- ↑ Donald Crafton (1982). Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898-1928. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-03083-7.

- ↑ "Dinos Parade across the Silver Screen". San Diego Natural History Museum. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011.

- ↑ Glut, Donald F.; Brett-Surman, Michael K. (1997). "Dinosaurs and the media". In Farlow, James; Brett-Surman, Michael K. The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 675–706. ISBN 978-0-253-33349-0.

- ↑ Boyar, Jay (April 8, 1985). "TALE OF BABY DINOSAUR IS A REAL DOG OF A FILM". The Orlando Sentinel.

- ↑ Delahoyde, Michael. "Baby: Secret of the Lost Legend". Dino-Source. www.wsu.edu.

- 1 2 3 4 Gould, S.J. (1991). Bully for Brontosaurus: Reflections in Natural History. W. W. Norton & Co. pp. 540pp.

- ↑ "Evolution of the Company Symbol". Sinclair Oil Corporation. 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑ "Topics of The Times: Leapin' Lizards!". The New York Times. 1989-10-11. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- ↑ Larimore, Rachael (April 7, 2015). "Dino-Mite! Study Suggests That the Brontosaurus Really Did Exist.". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ↑ "Why Do We Love the Brontosaurus?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ↑ Laden, Greg (April 8, 2015). "Bully for Brontosaurus". Greg Laden's Blog. ScienceBlogs. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ↑ Wedel, Matt (7 April 2015). "Welcome back, Brontosaurus! And other first thoughts on Tschopp et al. (2015)". Sauropod Vertebra Picture of the Week. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ↑ "Did You Ever Think You'd See The Day? THE BRONTOSAURUS EXISTS ONCE AGAIN!". perezhilton.com. 7 April 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ↑ Callaway, Ewen (7 April 2015). "Beloved Brontosaurus makes a comeback". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.17257. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ↑ "Brontosaurus is back! Brontosaurus is a unique genus after all". Science Daily. PeerJ. 7 April 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ↑ Devlin, Hannah (7 April 2015). "Brontosaurus is back! New analysis suggests genus might be resurrected". Science. The Guardian. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

External links

-

Media related to Brontosaurus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Brontosaurus at Wikimedia Commons -

Wikijunior Dinosaurs/Brontosaurus at Wikibooks

Wikijunior Dinosaurs/Brontosaurus at Wikibooks - Is Brontosaurus Back? (Youtube video, 11 minutes, 2015)