Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel

|

Logo of the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Official name | Hugh L. Carey Tunnel |

| Location | Brooklyn–Manhattan, New York City, New York, United States |

| Coordinates | 40°41′45″N 74°00′49″W / 40.695833°N 74.013611°W |

| Route |

|

| Crosses | East River |

| Operation | |

| Opened | May 25, 1950 |

| Operator | MTA Bridges and Tunnels |

| Traffic | 45,337 (2010)[1] |

| Toll | As of March 22, 2015, $8.00 (cash); $5.54 (New York State E-ZPass) |

| Technical | |

| Length | 9,117 feet (2,779 m) |

| Number of lanes | 4 |

| Tunnel clearance | 12 feet 1 inch (3.68 m) |

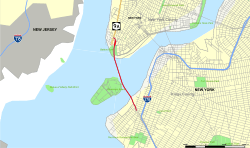

| Route map | |

| |

The Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel is a toll road in New York City that crosses under the East River at its mouth, connecting Brooklyn with Manhattan. The tunnel nearly passes underneath Governors Island, but does not provide vehicular access to the island. It consists of twin tubes, carrying four traffic lanes, and at 9,117 feet (2,779 m) is the longest continuous underwater vehicular tunnel in North America.[2] It was opened to traffic in 1950 and currently carries the Interstate 478 (I-478) designation; formerly, it was New York State Route 27A (NY 27A). The tunnel was officially renamed after former New York Governor Hugh Carey in 2010.

Description

The tunnel extends from the southern tip of Manhattan to Brooklyn's Red Hook neighborhood. The Battery in the tunnel's name refers to the southernmost tip of Manhattan, site of an artillery battery during the earliest days of New York City. The tunnel is owned by the City of New York and operated by the MTA Bridges and Tunnels, an affiliate agency of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. It has a total of four ventilation buildings: two in Manhattan, one in Brooklyn, and one on Governors Island that can completely change the air inside the tunnel every 90 seconds.

The tunnel carries 26 express bus routes that connect Manhattan with Brooklyn or Staten Island. They are the BM1, BM2, BM3, and BM4 operated by the MTA Bus Company, and the X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X7, X8, X9, X10, X11, X12, X14, X15, X17A, X17C, X19, X27, X28, X31, X37, X38, and X42, operated by MTA New York City Transit.

History

Construction began on October 28, 1940 by the New York City Tunnel Authority, with a groundbreaking ceremony attended by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[2][3][4] A large part of Little Syria, a mostly Christian Syrian/Lebanese neighborhood centered around Washington Street, was razed to create the entrance ramps for the tunnel. The shops and residents of Little Syria later moved to Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn.[5] The tunnel was designed by Ole Singstad and partially completed when World War II brought a halt to construction. After the War, the Triborough Bridge Authority was merged with the Tunnel Authority, allowing the new Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA) to take over the project. TBTA Chairman Robert Moses directed the tunnel be finished with a different method for finishing the tunnel walls. This resulted in leaking and, according to Robert Caro, the TBTA fixed the leaks by using a design almost identical to Singstad's original.[6] The tunnel opened to traffic on May 25, 1950.[7]

Robert Moses attempted to scuttle the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel proposal and have a bridge built in its place. Many objected to the proposed bridge on the grounds that it would spoil the dramatic view of the Manhattan skyline, reduce Battery Park to minuscule size and destroy what was then the New York Aquarium at Castle Clinton. Moses remained adamant, and it was only an order from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, via military channels, which restored the tunnel project, on the grounds that a bridge built seaward of the Brooklyn Navy Yard would prove a hazard to national defense. This edict was issued in spite of the fact that the Manhattan Bridge and the Brooklyn Bridge were already seaward of the Navy Yard.

On December 8, 2010, New York State legislators voted to rename the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel after former Governor Hugh Carey.[8] The tunnel was officially renamed the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel on October 22, 2012.[9]

The tunnel was closed in preparation for Hurricane Sandy and completely flooded on October 29, 2012, after a severe storm surge.[10] It reopened on November 13 following a cleanup process that included the removal of an estimated 86 million gallons (326 million liters) of water. The tunnel was the last New York City river crossing to reopen.[11]

Tolls

Starting on March 22, 2015, the cash toll is $8.00 per car or $3.25 per motorcycle. E‑ZPass users with transponders issued by the New York E‑ZPass Customer Service Center pay $5.54 per car or $2.41 per motorcycle. [12]

Interstate 478

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by MTA Bridges and Tunnels | ||||

| Length: | 2.14 mi[13] (3.44 km) | |||

| Existed: | 1971 – present | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| South end: |

| |||

| North end: |

| |||

| Highway system | ||||

| ||||

I-478 is the unsigned designation for the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel and its approaches. Its south end is at I-278 in Brooklyn, and its north end is at NY 9A (West Side Highway) in Lower Manhattan. As originally planned, I-478 would have continued north to I-78 at the Holland Tunnel via the now-canceled underground Westway project.

The I-478 number was considered for other routes as well, including the following:

- The Lower Manhattan Expressway branch along the Manhattan Bridge, between I-78 (which was to use the branch to the Williamsburg Bridge) and I-278 (1958–1971)

- The Grand Central Parkway between I-278 and I-678 (1971)

Before I-478 was moved to the Westway project in 1971, that project was planned as I-695, which would have continued north along the Henry Hudson Parkway to the George Washington Bridge (I-95).

See also

.svg.png) New York Roads portal

New York Roads portal

References

Notes

- ↑ "2008 Traffic Data Report for New York State" (PDF). New York State Department of Transportation. Appendix C. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- 1 2 "Hugh L. Carey Tunnel (formerly Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel)". MTA Bridges & Tunnels. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- ↑ "President Breaks Ground for Tunnel". The New York Times. October 29, 1940. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Informal Remarks At The Ceremonies Incident To Ground Breaking For The Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel - NARA - Wikimedia Commons". Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- ↑ Benson, Kathleen; Kayal, Philip M. (2002). Community of Many Worlds: Arab Americans in New York City. New York: Museum of the City of New York. p. 18. ISBN 0-8156-0739-3.

- ↑ Caro

- ↑ Ingraham, Joseph C. (May 26, 1950). "Brooklyn Tunnel Costing $80,000,000 Opened By Mayor". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ↑ Grynbaum, Michael M.; Kaplan, Thomas (December 8, 2010). "Queensboro Bridge and Brooklyn-Battery to Be Renamed". The New York Times.

- ↑ Durkin, Erin (October 22, 2012). "Battery Tunnel renamed after former New York governor Hugh L. Carey". Daily News. New York City. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ↑ Lanzano, Louis (October 30, 2012). "New York wakes up to devastation after superstorm Sandy". Perth Now. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ↑ Mann, Ted (November 13, 2012). "All Tunnels Cleared as Traffic Returns to Hugh Carey". Metropolis. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ↑ "Toll Information". MTA Bridges & Tunnels. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Route Log and Finder List - Interstate System: Table 2". FHWA. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

Further reading

- Caro, Robert A., The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, New York: Knopf, 1974.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. |

- nycroads.com about Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel

- "Sandhogs Toughest Job", September 1947, Popular Science

- Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel Construction Scenes (1947)—from the MTA's YouTube web link (1:18 video clip)

- Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel: Sixty Years—from the MTA's YouTube web link (6:13 video clip)

.svg.png)