Camp Nelson Civil War Heritage Park

|

Camp Nelson | |

|

| |

| |

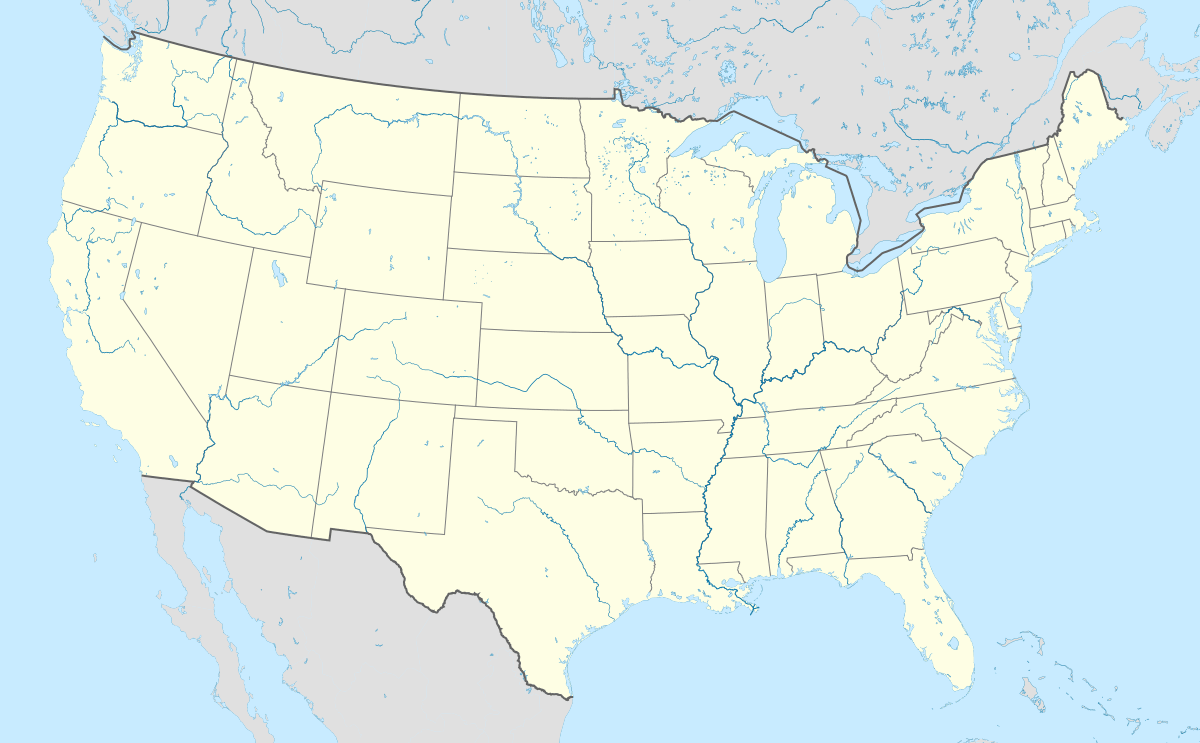

| Location | Jessamine County, Kentucky, USA |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Nicholasville, Kentucky |

| Coordinates | 37°47′16″N 84°35′53″W / 37.78778°N 84.59806°WCoordinates: 37°47′16″N 84°35′53″W / 37.78778°N 84.59806°W |

| Architect | U.S. Army of the Ohio Eng. Corps; Simpson, Lt.Col. J.H. |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| NRHP Reference # | 00000861 (NRHP),[1] 13000286 (NHL)[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | March 15, 2001 |

| Designated NHLD | February 27, 2013[2] |

The Camp Nelson Civil War Heritage Park is a 525-acre (2.12 km2) historical museum and park located in southern Jessamine County, Kentucky, 20 miles (32 km) south of Lexington, Kentucky. It was established in 1863 as a depot for the Union army during the Civil War. It became a recruiting ground for new soldiers from eastern Tennessee and escaped slaves, many of whom trained to be soldiers.[3]

Early history

Camp Nelson was established as a supply depot for Union invasions into Tennessee. It was named for Major General William "Bull" Nelson, who had recently been murdered.[4] It was placed near Hickman Bridge, the only bridge across the Kentucky River upriver from the state capital (Frankfort, Kentucky). The site was selected to protect the bridge, to have a base of operations in central Kentucky, and to prepare to attack the Cumberland Gap and eastern Tennessee. The camp was also used as a site to train new soldiers for the Union army. The Kentucky River's steep palisades contributed to the selection of the site—they would help defend the camp from Confederate attack.[5]

Camp Nelson may have been the best choice for a central Kentucky depot, but it was inadequate. When Union Major General Ambrose Burnside attacked the Cumberland Gap and Knoxville, Tennessee, Camp Nelson's distance from the Gap and Knoxville, combined with lack of railroads and the weather, hampered the Union advance.[6] When overall Union commander Ulysses S. Grant visited Camp Nelson in January 1864, he was displeased, observing that "no portion of our supplies can be hauled by teams from Camp Nelson". The situation of the camp had not improved by spring of 1864, and Grant leaned toward abandoning it entirely. William Tecumseh Sherman advocated that its role be diminished instead, which saved Camp Nelson. It took on the role of training black soldiers, who volunteered for the US Colored Troops.[7]

In July 1863 and June 1864, Union forces feared that the camp might be attacked by Confederate general John Hunt Morgan, who was conducting raids in Kentucky and other border states, as well as Ohio. In 1863 Morgan was headed for Indiana and Ohio in his most famous raid. It was never confirmed whether he intended to attack the camp in 1864.[8]

Black history

In August 1863 thousands of slaves forced to build railroads for the Union army were stationed at Camp Nelson.[4] They had escaped to Union lines, or joined Union forces which had taken over rebel areas. The army needed the help of their work. These former slaves, at least 3,000 in number, were the primary builders of Camp Nelson, starting with fortifying Hickman Bridge on May 19, 1863. Prior to Lincoln issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, the Army declared such former slaves as "contraband" and refused to return them to the southern slaveholders, as the Confederacy demanded. The Army did use former slaves as laborers. No blacks enlisted in the USCT in Kentucky until 1864, whereas in other border states, former slaves started enlisting in October 1863.[9]

At Camp Nelson 10,000 African Americans were emancipated from slavery in exchange for service in the Union army. These soldiers sometimes brought their families to Camp Nelson; such refugees totaled 3,060 and were cared for by missionaries. At one point, in November 1864, Camp Nelson was not a legal place of refuge for slaves. The Union soldiers forced out 400 women and children to leave the camp; the refugees suffered 102 deaths due to severe weather until allowed to return to camp.[4] Some 1300 refugees died at Camp Nelson, reflecting the high rate of infectious disease at camps.[4] Camp Nelson was the smallest of the three locations where blacks were trained to become Union soldiers; the others were in Boston, and New Orleans. In a more rural area than the other former facilities, Camp Nelson is the only one whose land was never developed after the war for other purposes.[10]

The most African-American recruits arrived at the camp between June and October 1864, with 322 men enlisting on a single day on July 25. After that, only 20 more recruits arrive in 1864. In January, 15 signed up, and from February to April 1865, there were six.[11] Among the units raised at Camp Nelson were the 5th and 6th U.S. Colored Cavalry Regiments and the 114th and 116th Colored Heavy Artillery Regiments.[4] After the war, Camp Nelson was a center for giving ex-slaves their emancipation papers. Many have considered the camp as their "cradle of freedom".[4]

After the war, the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) operated a soldiers' home for a time at Camp Nelson, in former barracks. It was one of a series of homes and rest houses they operated for soldiers.

Today

Presently, 525 acres (2.12 km2) of the original property are preserved as the Camp Nelson Civil War Heritage Park. Most of the buildings at the camp were sold.[10] The camp is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and was declared a National Historic Landmark District in March 2013.[12]

Camp Nelson is currently controlled by the Jessamine County Fiscal Court. The county and some local leaders would like to transfer Camp Nelson to the National Park Service. The site was designated as part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, which runs through several states and has sites in Canada and the Antilles. In 2008 U.S. Representative Ben Chandler was studying funding issues related to such a transfer of property.[10]

The Oliver Perry House is the only surviving structure from its years as a camp. It was built in about 1846 for the newlywed couple of Oliver Perry and the former Fannie Scott. General Burnside confiscated the house during the war to serve as officers quarters. In many official letters, the house was called the "White House". It currently is operated as a historic house museum for the park.[13]

The park has more than a mile of walking paths. Ghost tours are occasionally available.[14]

Camp Nelson National Cemetery is two miles to the south.[3] It has organized records of burials online so that families may trace relatives buried here, in addition to those who trained or lived at the camp.

Gallery

-

Tent display in Interpretive Center

-

Gray building at Camp Nelson

See also

- Colored Soldiers Monument in Frankfort

- United States Sanitary Commission, photo of Camp Nelson soldiers' home

- 12th Regiment Heavy Artillery U.S. Colored Troops, organized and sometimes stationed at Camp Nelson

Notes

- ↑ National Park Service (2008-04-15). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/25/13 THROUGH 3/29/13". National Park Service. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- 1 2 Strecker p.39

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kleber p.158

- ↑ Sears pp.21–23.

- ↑ Sears p.28.

- ↑ Sears pp.29, 30.

- ↑ Sears p.42.

- ↑ Sears, pp.33, 34, 37

- 1 2 3 ["Nelson's stock soars"], The Kentucky Civil War Bugle Second Quarter, 2008, pg.1-8

- ↑ Sears p.39

- ↑ "AMERICA'S GREAT OUTDOORS: Secretary Salazar, Director Jarvis Designate 13 New National Historic Landmarks". US Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ↑ "Camp Nelson", Jessamine County, KY official site, accessed November 7, 2008

- ↑ CAMP NELSON CIVIL WAR HERITAGE PARK — CLASSES, EVENTS & CAMPOUTS, Kentucky Ghosthunters, Accessed November 7, 2008

References

- Official site

- Kleber, John E. (1992). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- Sears, Richard D. (2002). Camp Nelson, Kentucky: A Civil War History. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2246-5.

- Strecker, Zoe Ayn (2007). Kentucky: A Guide to Unique Places. Globe Pequot. ISBN 0-7627-4201-1.

.svg.png)