The Celluloid Closet

| The Celluloid Closet | |

|---|---|

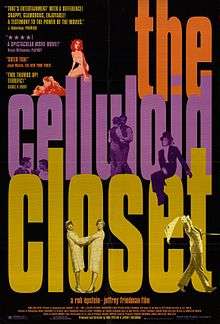

Movie poster for The Celluloid Closet. | |

| Directed by |

Rob Epstein Jeffrey Friedman |

| Produced by |

Rob Epstein Jeffrey Friedman Howard Rosenman (executive producer) |

| Written by |

Vito Russo Rob Epstein Jeffrey Friedman Sharon Wood Armistead Maupin |

| Starring | See below |

| Narrated by | Lily Tomlin |

| Music by | Carter Burwell |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Classics |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1,400,591 |

The Celluloid Closet is a 1995 American documentary film directed and written by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman. The film is based on Vito Russo's book of the same name first published in 1981 and on lecture and film clip presentations he gave in 1972–82. Russo had researched the history of how motion pictures, especially Hollywood films, had portrayed gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender characters.

The film was given a limited release in select theatres, including the Castro Theatre in San Francisco, in April 1996, and then shown on cable channel HBO.

Overview

The documentary interviews various men and women connected to the Hollywood industry to comment on various film clips and their own personal experiences with the treatment of LGBT characters in film. From the sissy characters, to the censorship of the Hollywood Production Code, the coded gay characters and cruel stereotypes to the changes made in the early 1990s.[1]

Vito Russo wanted his book to be transformed into a documentary film and helped out on the project until he died in 1990. Some critics of the documentary noted that it was less political than the book and ended on a more positive note. However, Russo had wanted the documentary to be entertaining and to reflect the positive changes that had occurred up to 1990.

Production

Russo approached Epstein about making a film version of The Celluloid Closet and even wrote a proposal for the film version in 1986.[2] But it wasn’t until Russo died in 1990 that Epstein and Friedman gained any traction on the project. After his death, Channel 4 in England approached the filmmakers about the film, and offered development funding in order to write a treatment, “and most importantly to determine if it would even be possible to obtain the film clips from studios.”[2]

After developing the project for years, fundraising remained the biggest obstacle. Lily Tomlin, the actress and comedian who would narrate the film, launched a direct mail fundraising campaign in Vito Russo’s honor.[2] She also headlined a benefit at the Castro Theatre, which featured Robin Williams, Harvey Fierstein, and drag star Lypsinka. Individuals such as Hollywood producer Steve Tisch, James Hormel, and Hugh Hefner offered “significant support” and the filmmakers also began to receive foundation funding from the Paul Robeson Fund, the California Council for the Humanities, and the Chicago Resource Center.[2]

European television again played an important role in funding the project, when ZDF/arte signed on, but it wasn’t until the filmmakers reached out to HBO that they were able to begin production. In May 1994, “Lily Tomlin contacted Michael Fuchs, chairman of HBO, on behalf of the project. Epstein, Friedman, Tomlin, and Rosenman flew to New York for a meeting with Fuchs and HBO Vice President Sheila Nevins. At that meeting, HBO committed to supply the remainder of the budget.”[2]

Credits

The following people are interviewed for the documentary.

- Lily Tomlin (narrator)

- Jay Presson Allen

- Susie Bright

- Quentin Crisp

- Tony Curtis

- Richard Dyer

- Arthur Laurents

- Armistead Maupin

- Whoopi Goldberg

- Jan Oxenberg

- Harvey Fierstein

- Mrs. Gustav Ketterer

- Gore Vidal

- Farley Granger

- Paul Rudnick

- Shirley MacLaine

- Barry Sandler

- Mart Crowley

- Antonio Fargas

- Tom Hanks

- Ron Nyswaner

- Daniel Melnick

- Harry Hamlin

- John Schlesinger

- Susan Sarandon

- Stewart Stern

DVD

In 2001, the DVD edition of the documentary includes a crew audio commentary, a second audio commentary with the late Russo, an interview Russo gave in 1990, and some deleted interviews put together into a second documentary titled Rescued from the Closet.

Impact

The Celluloid Closet had precursors in Parker Tyler's 1972 book Screening the Sexes and Richard Dyer's 1977 Gays and Film.[3]

The film was released at a dramatic time in gay history. It seemed like success was on the horizon when Bill Clinton was elected president. He had been the first major party presidential candidate to court and to promise openly to gay voters. However, the movement faced a huge public setback when "Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell" was passed.[4] In response to these obstacles, the LGBT-rights movement became increasingly media focused, realizing that the images projected into the world negatively affected perceptions of homosexuality. In 1994, the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation was formed as a national organization. The Celluloid Closet came out in 1996, as marches and protests against homosexual representation in film and television grew.

"Protests [were] aimed specifically at some of Hollywood's biggest and most prestigious films, including The Silence of the Lambs, which features a crazed transvestite who kills and flays women, and JFK, which has a scene in which gays alleged to be conspirators in the Kennedy assassination cavort in sadomasochistic fun and games".[5] The article quoted above features an interview with Kate Sorensen, a member of Queer Nation, an organization that helped to organize the protests: "‘Every lesbian and bisexual character in these films is accused of being a psychotic killer ... And the girl never gets the girl. I'm tired of that.’” Gay activists across the country attacked films like these, where the homosexual character is portrayed as a disgustingly erotic killer. Protesters would mince around the filming area during outdoor scenes as well as around ticket lines when the film came out.

It was believed that these portrayals reflected "a perverse fear of AIDS or the rising intolerance that [had] caused an increase in hate crimes of all kinds. Still, Hollywood's treatment of gays [hadn’t] helped. With few exceptions, the homosexual characters in films are creepy misfits or campy caricatures".[5] The release of The Celluloid Closet further emphasized the twisted way homosexuals have been depicted throughout history. Addressing specific issues that were pertinent at the time, Russo exposes the existence of Hollywood homosexuals as well as the uncontrolled homophobia that keeps homosexuality in the closet on and off the screen.[6]

"Russo essentially did for film what ACT UP did for AIDS awareness ... he opened up a world and a culture that had almost never been discussed before under any circumstances, exposing prejudices and hurts”.[7] The film continued to motivate the need for positive representation of homosexuals. The Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation held seminars for staff at Columbia Pictures and Carolco. In addition, Hollywood Supports, a service organization with the mission to combat AIDS phobia and homophobia in the entertainment industry, was founded.[5]

Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) gives an award called the Vito Russo Award to openly gay or lesbian people within the Hollywood film industry who advance the cause of fighting homophobia.

In addition the film was honored with four Emmy Award nominations in 1996. It was nominated for Outstanding Individual Achievement in Informational Programming for editing, sound recording and director of photography. It was also nominated for Outstanding Informational special. Additionally, the film received both a Peabody Award and recognition at the 1996 Sundance Film Festival by winning the Freedom of Expression award.

Films

The following is a list of film excerpts in The Celluloid Closet.

- 48 Hrs. (1982)

- The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994)

- Advise and Consent (1962)

- Algie the Miner (1912)

- An Officer and a Gentleman (1982)

- Another Country (1984)

- Basic Instinct (1992)

- Behind the Screen (1916)

- Ben-Hur (1959)

- The Boys in the Band (1970)

- Boys on the Side (1995)

- Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

- Bringing Up Baby (1938)

- The Broadway Melody (1929)

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

- Cabaret (1972)

- Caged (1950)

- Calamity Jane (1953)

- Call Her Savage (1932)

- Car Wash (1976)

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958)

- The Children's Hour (1961)

- The Chocolate War (1988)

- The Color Purple (1985)

- Continental Divide (1981)

- Crossfire (1947)

- Cruising (1980)

- The Crying Game (1992)

- Dancing Lady (1933)

- Desert Hearts (1985)

- The Detective (1968)

- Dickson Experimental Sound Film (1895)

- Dracula's Daughter (1936)

- Dream a Little Dream (1989)

- Edward II (1991)

- Fame (1936)

- The Fan (1981)

- A Florida Enchantment (1914)

- The Fox (1967)

- Freebie and the Bean (1974)

- Fried Green Tomatoes (1991)

- The Gay Divorcee (1934)

- Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953)

- Gilda (1946)

- Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

- Go Fish (1994)

- Hairspray (1988)

- Heathers (1989)

- Heaven Help Us (1985)

- The Hours and Times (1991)

- The Hunger (1983)

- In a Lonely Place (1950)

- Johnny Guitar (1954)

- The Killing of Sister George (1968)

- La Cage Aux Folles (1978)

- Ladies They Talk About (1933)

- Lianna (1983)

- The Living End (1992)

- Longtime Companion (1990)

- The Lost Weekend (1945)

- Lover Come Back (1961)

- Making Love (1982)

- The Maltese Falcon (1941)

- Manslaughter (1922)

- Midnight Express (1978)

- Mo' Money (1992)

- Morocco (1930)

- Mrs. Doubtfire (1993)

- My Beautiful Laundrette (1985)

- My Bodyguard (1980)

- My Own Private Idaho (1991)

- Myrt and Marge (1933)

- Next Stop, Greenwich Village (1976)

- Night Shift (1982)

- North Dallas Forty (1979)

- Our Betters (1933)

- Parting Glances (1986)

- Partners (1982)

- Personal Best (1982)

- Philadelphia (1993)

- Pillow Talk (1959)

- Poison (1991)

- Queen Christina (1933)

- Rebecca (1940)

- Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

- Red River (1948)

- Repo Man (1984)

- Rope (1948)

- The Sergeant (1968)

- The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

- Silkwood (1983)

- The Soilers (1923)

- Some Like It Hot (1959)

- Spartacus (1960)

- Suddenly, Last Summer (1959)

- Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971)

- Swoon (1992)

- Tarzan and His Mate (1934)

- Tea and Sympathy (1956)

- Teen Wolf (1985)

- Their First Mistake (1932)

- Thelma and Louise (1991)

- Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974)

- Top Hat (1935)

- Torch Song Trilogy (1988)

- Vanishing Point (1971)

- Victim (1961)

- Victor Victoria (1982)

- A View from the Bridge (1962)

- Walk on the Wild Side (1962)

- A Wanderer of the West (1927)

- The Warriors (1979)

- The Wedding Banquet (1993)

- Wild at Heart (1990)

- Windows (1980)

- Wings (1927)

- Wonder Bar (1934)

- Young Man with a Horn (1950)

See also

- Wendy Braitman, associate producer

- Lavender marriage

- List of lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender-related films

References

- ↑ "The Celluloid Closet (1995)". imdb.com. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Telling Pictures: The Celluloid Closet". tellingpictures.com. 2004. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (1981-08-04), "The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies", Soho News, retrieved 2010-02-25

- ↑ "The Gay Rights Movement, U. S.". The Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Encyclopedia. 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 Simpson, Janice C. (April 6, 1992). "Out of the Celluloid Closet: Gay Activists are on a Rampage Against Negative Stereotyping and Other Acts of Homophobia in Hollywood". TIME. p. 65. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ Smelik, Anneke (1998). "Gay and Lesbian Criticism". In Hill, John; Church Gibson, Pamela. The Oxford Guide to Film Studies (PDF). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 135.

- ↑ Barrios, Richard (2005). Screened Out: Playing Gay in Hollywood from Edison to Stonewall. London: Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 978-0415923293.