Claire Lee Chennault

| Claire Lee Chennault | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

September 6, 1893 Commerce, Texas, U.S. |

| Died |

July 27, 1958 (aged 64) New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Buried at | Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1917–1945 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands held | 1st American Volunteer Group (Flying Tigers) |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

Army Distinguished Service Medal (2) Distinguished Flying Cross (2) Order of the Cloud and Banner Commander of the Order of the British Empire Order of Blue Sky and White Sun |

| Spouse(s) |

Nell Thompson (1911-1946) Anna Chennault (née Chen Xiangmei) (1947-1958, his death) |

Claire Lee Chennault (September 6, 1893 – July 27, 1958) was an American military aviator best known for his leadership of the "Flying Tigers" and the Republic of China Air Force in World War II. Chennault was a fierce advocate of "pursuit" or fighter-interceptor aircraft during the 1930s when the U.S. Army Air Corps was focused primarily on high-altitude bombardment. Chennault retired from the United States Army in 1937, and went to work as an aviation adviser and trainer in China. Starting in early 1941, Chennault commanded the 1st American Volunteer Group (nicknamed Flying Tigers). One mission which never came to fruition was the bombing of Japanese cities; the bombers did not arrive before Pearl Harbor. (B-29's started bombing from China in 1944, but they were not under Chennault's command.) He headed both the volunteer group and the uniformed U.S. Air Force units that replaced it in 1942. He feuded constantly with General Joseph Stilwell, the U.S. Army commander in China, and helped China's leader Chiang Kai-shek to convince President Roosevelt to remove Stilwell in 1944. The China-Burma-India theater was strategically essential in order to fix many vital elements of the Imperial Japanese Army on the Chinese mainland to limit their use against Allied forces advancing towards Japan in the two Pacific campaigns.

The surname Chennault is French[Note 1] and is often pronounced shen-o. However, his American family pronounced the name "shen-AWLT."[2]

Early life and education

Chennault was born in Commerce, Texas, to John Stonewall Jackson Chennault and Jessie (nėe Lee) Chennault. He grew up in the Louisianan towns of Gilbert and Waterproof. He began misrepresenting his year of birth as either 1889[3] or 1890, possibly because he was too young to attend college after he graduated from high school, so his father added three years to his age.[4][5]

Military career

Chennault attended Louisiana State University between 1909 and 1910 and underwent ROTC training. He and Nell moved to West Carroll Parish where he served as principal of Kilbourne School from 1913 - 1915.[6] At the onset of World War I, he graduated from Officers' School at Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indiana, and was transferred to the Aviation Division of the Army Signal Corps.[7] He learned to fly in the Army Air Service during World War I. Following the war he graduated from pursuit pilot training at Ellington Field, Texas, on April 23, 1922, and remained in the service after it became the Air Corps in 1926. Chennault became the Chief of Pursuit Section at Air Corps Tactical School in the 1930s.[8]

Leadership

Into the mid-1930s Chennault led and represented the 1st Pursuit Group of the Montgomery, Alabama-based Army Air Corps aerobatic team the "Three Musketeers".[9] The group performed at the 1928 National Air Races. In 1932, as a pursuit aviation instructor at Maxwell Field, Chennault re-organized the team as "Three Men on the Flying Trapeze".

Resignation

Poor health (deafness and chronic bronchitis) and disputes with superiors and the fact that he was passed over as unqualified for promotion, led Chennault to resign from the military on April 30, 1937; he separated from the service at the rank of captain. As a civilian, he then was induced to go to China and join a small group of American civilians training Chinese airmen.[10]

Before the Flying Tigers

Chennault arrived in China in June 1937. He had a three-month contract at a salary of $1,000 per month, charged with making a survey of the Chinese Air Force. Soong Mei-ling, or "Madame Chiang" as she was known to Americans, was in charge of the Aeronautical Commission and thus became Chennault's immediate supervisor. Upon the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War that August, Chennault became Chiang Kai-shek's chief air adviser, training Chinese Air Force pilots as well as sometimes flying scouting missions in an export Curtiss H-75 fighter. His duties also included organizing the "International Squadron" of mercenary pilots.[11]

However, Soviet bomber and fighter squadrons increasingly took over from China's battered units, and in the summer of 1938 Chennault went to Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province in western China, to train and organize a new Chinese Air Force along the American model.[12][13]

On October 21, 1939, Chennault, accompanied by four Chinese officials, boarded the Pan American Airways Boeing B-314 California Clipper in Hong Kong, arriving at San Francisco on October 26, on a special mission for Chiang Kai-shek. By 1940, seeing that the Chinese Air Force had collapsed because of ill-trained Chinese pilots and shortage of equipment, Chiang again sent Chennault, accompanied by Chinese Air Force General Pang-Tsu Mow, to the United States to meet with banker Dr. T. V. Soong in Washington, D.C., with the following directed purpose: "to get as many fighter planes, bombers, and transports as possible, plus all the supplies needed to maintain them and the pilots to fly the aircraft." Together, they departed on October 15, 1940, from Chungking, China, transited at Hong Kong where they boarded Pan Am Boeing B-314 American Clipper on November 1, arriving at San Francisco on November 14. They reported to the Chinese Ambassador to the United States, Hu Shih.[14]

Creation of the American Volunteer Group, the "Flying Tigers"

Chennault's mission to Washington ultimately brought up the idea of creating an American Volunteer Group of pilots and mechanics to serve in China. By then Dr. Soong had already begun negotiations for an increase in financial aid with U.S. Secretary of Commerce and Federal Loan Administrator Jesse H. Jones on October 17.[15]

Washington provided the money. How to obtain the shopping list of aircraft, aviation supplies, volunteers and funds for the Bank of China were further discussed in a meeting held at the home of Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr. with Captain Chennault, Dr. Soong, and General Mow on December 21.[16] On April 25, 1941, the United States and China formally signed a $50 million stabilization agreement to support the Chinese currency. By December 23, 1940, upon approval by the War Department, State Department and the President of the United States, an agreement was reached to provide China the 100 P-40B Tomahawk aircraft which had originally been built for Britain, but which the British were persuaded to give up in preference for newer models rapidly being built. With an agreement reached, General Mow returned to China aboard the SS Lurline, departing from Los Angeles, California on January 24, 1941. Chennault followed shortly after with a promise from the War Department and President Roosevelt to be delivered to Chiang Kai-shek that several shipments of P-40C fighters were forthcoming along with pilots, mechanics, and aviation supplies.[14]

The 100 planes were crated and sent to Burma on third country freighters during spring 1941. At Rangoon, they were unloaded, assembled and test flown by personnel of Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company (CAMCO) before being delivered to the AVG training unit at Toungoo.[Note 2] Their first battle occurred on December 20, 1941 with aircraft flying out of Kunming.[17]

CAMCO was able to deliver 99 Tomahawks before war broke out. (Many of those were later destroyed in training accidents.) The 100th fuselage was trucked to a CAMCO plant in Loiwing, China, and later made whole with parts from damaged aircraft. Shortages in equipment with spare parts almost impossible to obtain in Burma along with the slow introduction of replacement fighter aircraft were continual impediments, although the AVG did receive 50 replacement P-40E fighters from USAAF stocks that were originally scheduled for shipment to Great Britain but cancelled due to the Tomahawk's inferior flight performance against German fighters.[14]

Chennault was able to recruit some 300 American pilots and ground crew, posing as tourists, who were adventurers or mercenaries, not necessarily idealists out to save China. But under Chennault they developed into a crack fighting unit, always going against superior Japanese forces. They became the symbol of America's military might in Asia.[18] They became the Flying Tigers.[14]

Plan to bomb Japan

By early 1941 the U.S. was preparing to send American planes flown by American pilots under American command, but wearing Chinese uniforms, to fight the Japanese invaders and even to bomb Japanese cities, all using the Flying Tigers, as soon as they were in place. A year before the U.S. officially entered the war, Chennault developed an ambitious plan for a sneak attack on Japanese bases. His Flying Tigers would use American bombers and American pilots, all with Chinese markings. He made the fantastic claim that a handful of fliers and planes could win the war single handed.

The U.S. military was opposed to this scheme and raised obstacles, noting that being able to reach Japan depended on Chiang Kai-shek's troops being able to build and protect airfields and bases close enough to Japan, which they doubted he could do. They also had little confidence in Chennault having pushed him out of the air forces earlier. Despite the military advice the idea of China winning the war with Japan swiftly with only a few American men and planes was too tempting to the civilian leaders. It was adopted by top civilian officials including Treasury Secretary Morgenthau and President Roosevelt himself.[Note 3]

By October 1941, bombers and crews were on their way to China. However, the American attack never took place: The Nationalist Chinese had not built and secured any runways or bases close enough to reach Japan, just as the military brass had warned. The bombers and crews arrived after Pearl Harbor and were used for the war in Burma, for they lacked the range to reach Japan from the secure bases in China.[19][20][21]

Flying Tigers

Just weeks after the Japanese air Attack on Pearl Harbor (Sunday morning, December 7, 1941), the first news reports released to the public pertaining to Chennault's war exploits occurred on December 20, 1941, when senior Chinese officials in Chungking that Saturday evening released his name to United Press International reporters to commemorate the first aerial attack made by the international air force called the American Volunteer Group (AVG).[22][23][24][25] These American flyers encountered 10 Japanese aircraft heading to raid Kunming and successfully shot down four of the raiders. Thus, Colonel Claire Chennault became America's "first military leader" to be publicly recognized for striking a blow against the Japanese military forces. However, at the time Chennault was not a member of the American military having been forced out as a captain. He was an American civilian mercenary who was paid and promoted to colonel by Chiang Kai-Shek. In 1948, Chennault made the controversial claim that General Clayton Bissell had not informed him of the subsequent Doolittle raid, and that the raiders took unnecessary casualties because of it but was never able to demonstrate how telling him could have helped. He was not even an American officer at the time.[26]

Based primarily out of Rangoon, Burma, and Kunming, Yunnan, Chennault's 1st American Volunteer Group (AVG) – better known as the "Flying Tigers" – began training in August 1941 and fought the Japanese for seven months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Chennault's three squadrons used P-40s, and his tactics of "defensive pursuit," formulated in the years when bombers were actually faster than intercepting fighter aircraft, to guard the Burma Road, Rangoon, and other strategic locations in Southeast Asia and western China against Japanese forces. As the commander of the Chinese Air Force flight training school at Yunnan-yi, west of Kunming, Chennault also made a great contribution by training a new generation of Chinese fighter pilots. The Flying Tigers were formally incorporated into the United States Army Air Forces in 1942. Prior to that, Chennault had rejoined the Army with the rank of colonel. He was later promoted to brigadier general and then major general, commanding the Fourteenth Air Force.

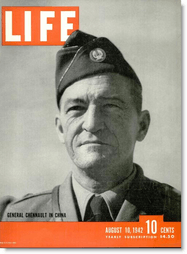

The first magazine photo coverage of Chennault took place within Life magazine in the Monday, August 10, 1942, issue. The first Time magazine photo coverage of Chennault took place in its Monday, December 6, 1943, issue.[27]

China-Burma-India theater

Throughout the war Chennault was engaged in a bitter dispute with the American ground commander, General Joseph Stilwell. Chennault believed that the Fourteenth Air Force, operating out of bases in China, could attack Japanese forces in concert with Nationalist troops. For his part, Stilwell wanted air assets diverted to his command to support the opening of a ground supply route through northern Burma to China. This route would provide supplies and new equipment for a greatly expanded Nationalist force of twenty to thirty modernized divisions. Chiang Kai-shek favored Chennault's plans, since he was suspicious of British colonial interests in Burma and was not prepared to begin major offensive operations against the Japanese. He was also concerned about alliances with semi-independent generals supporting the Nationalist government, and was concerned that a major loss of military forces would enable his Communist Chinese adversaries to gain the upper hand.

Good weather in November 1943 found the Japanese Army air forces ready to challenge Allied forces again, and they began night and day raids on Calcutta and the Hump bases while their fighters contested Allied air intrusions over Burma. In 1944, Japanese ground forces advanced and seized Chennault's forward bases. Slowly, however, the greater numbers and greater skill of the Allied air forces began to assert themselves. By mid-1944, Major General George Stratemeyer's Eastern Air Command dominated the skies over Burma; this superiority was never to be relinquished. At the same time, logistical support reaching India and China via the Hump finally reached levels permitting an Allied offensive into northern Burma. Chennault had long argued for expansion of the airlift, doubting that any ground supply network through Burma could provide the tonnage needed to re-equip Chiang's divisions. However, work on the Ledo Road overland route continued throughout 1944 and was completed in January 1945. Training of the new Chinese divisions commenced; however, predictions of monthly tonnage (65,000 per month) over the road were never achieved. By the time Nationalist armies began to receive large amounts of supplies via the Ledo Road, the war had ended. Instead, the airlift continued to expand until the end of the war, after delivering 650,000 tons of supplies, gasoline, and military equipment.

Postwar

Chennault, who, unlike Joseph Stilwell, had a high opinion of Chiang Kai-shek, advocated international support for Asian anti-communist movements. Returning to China, he purchased several surplus military aircraft and created the Civil Air Transport, (later known as Air America).[28] These aircraft facilitated aid to Nationalist China during the struggle against Chinese Communists in the late 1940s, and were later used in supply missions to French forces in Indochina[28] and the Kuomintang occupation of northern Burma throughout the mid- and late-1950s, providing support for the Thai police force. This same force supplied the intelligence community and others during the Vietnam conflict.

In 1951, a now-retired Major General Chennault testified and provided written statements to the Senate Joint Committee on Armed Forces and Foreign Relations, which was investigating the causes of the fall of China in 1949 to Communist forces. Together with Army General Albert C. Wedemeyer, Navy Vice Admiral Oscar C. Badger II, and others, Chennault stated that the Truman administration's arms embargo was a key factor in the loss of morale to the Nationalist armies.[29]

Chennault advocated changes in the way foreign aid was distributed, encouraged the U.S. Congress to focus on individualized aid assistance with specific goals, with close monitoring by U.S. advisers. This viewpoint may have reflected his experiences during the Chinese Civil War, where officials of the Kuomintang and semi-independent army officers diverted aid intended for the Nationalist armies. Shortly before his death, Chennault was asked to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee of the Congress. When a committee member asked him who won the Korean War, his response was blunt: "The Communists".

Memoirs

In 1949, Chennault published his memoirs Way of a Fighter. The book covers his entire life, but is especially detailed in recording his experience in China. The difficulties he faced in modernizing fighter tactics, even in emphasizing airpower as a weapon, are clearly explained. His disagreements with and criticisms of the theater commander, General Joseph Stilwell, trained in the infantry and unappreciative of the capabilities of airpower, constitute a major portion of the memoirs. The book ends with his retirement from the Air Force and his return to China six months later to aid the nation's recovery.

Death

Chennault was promoted to lieutenant general in the U.S. Air Force on July 18, 1958, nine days before his death on July 27, at the Ochsner Foundation Hospital in New Orleans.[30] He died of lung cancer. He is interred at Arlington National Cemetery (Section 2, 873).[31]

Personal life

Family

Chennault was twice married and had a total of ten children, eight by his first wife, the former Nell Thompson (1893–1977), an American of British ancestry, whom he met at a high school graduation ceremony and subsequently wed in Winnsboro, Louisiana, on December 24, 1911. The marriage ended in divorce in 1946, long after his service in China started. He had two daughters by his second wife, Chen Xiangmei (Anna Chennault), a young reporter for the Central News Agency whom he married on December 2, 1947. She became one of the Republic of China's chief lobbyists in Washington, D.C.

His children from the first marriage were John Stephen Chennault (1913–1977), Max Thompson Chennault (1914–2001), Charles Lee Chennault (1918–1967), Peggy Sue Chennault Lee (1919 - 2004), Claire Patterson Chennault (November 24, 1920 – October 3, 2011),[32] David Wallace Chennault (1923–1980), Robert Kenneth Chennault (1925–2006), and Rosemary Louise Chennault Simrall (September 27, 1928 – August 25, 2013).[33]

The Chennault daughters from the second marriage are Claire Anna Chennault (born 1948) and Cynthia Louise Chennault (born 1950), a professor of Chinese at the University of Florida, Gainesville.[34]

Claire P. Chennault, one of Claire Lee's sons, was a U.S. Army Air Corps and then U.S. Air Force officer from 1943 to 1966 and subsequent resident of Ferriday, Louisiana.[32]

Legacy

In December 1972, Chennault was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame, along with Leroy Grumman, Curtis LeMay and James H. Kindelberger. The ceremony was headed by retired Brigadier General Jimmy Stewart, and a portrait of Chennault by cartoonist Milton Caniff was unveiled. General Electric vice-president Gerhard Neumann, a former AVG crew chief and the technical sergeant who repaired a downed Zero for flight, spoke of Chennault's unorthodox methods and of his strong personality.[35]

Chennault was honored by the United States Postal Service with a 40¢ Great Americans series (1980–2000) postage stamp.[36][37]

Chennault is commemorated by a statue in the Republic of China's capital, Taipei, as well as by monuments on the grounds of the Louisiana State Capitol at Baton Rouge and at the former Chennault Air Force Base, now the commercial Chennault International Airport in Lake Charles. The Chennault Aviation and Military Museum, located near the entrance to Monroe Regional Airport, and Chennault Park, also in Monroe, are also named in his honor. Nell Martien Calloway, named for her grandmother, Nell Thompson Chennault, and the daughter of Rosemary Simrall and Simrall's first husband, Norman Hopkins Martien, Jr. (1926-2012), is the director of the Chennault Aviation and Military Museum in Monroe.[38][39]

A vintage Curtiss P-40 aircraft, nicknamed "Joy", is on display at the riverside war memorial in Baton Rouge, painted in the colors of the Flying Tigers. In 2006 the University of Louisiana at Monroe renamed its athletic teams the Warhawks, honoring Chennault's AVG Curtiss P-40 fighter aircraft nickname. A large display of General Chennault's orders, medals and other decorations has been on loan to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., by his widow Anna since the museum's opening in 1976.

For many years Chennault was viewed negatively within the People's Republic of China, due to his role against the Communist forces during the Chinese Civil War. However, this has changed slowly since the establishment of diplomatic relations between the PRC and the U.S., with Chennault being viewed more positively. In 2005, the "Flying Tigers Memorial" was built in Huaihua, Hunan Province, on one of the old airstrips used by the Flying Tigers in the 1940s. On the 65th anniversary of the Japanese surrender, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and PRC officials unveiled a statue of Chennault in Zhijiang County, Hunan.[40] The Kunming Flying Tigers Museum opened on December 20, 2012, on the 71st anniversary of the first combat in Kunming of the Flying Tigers. Chongqing is also home to a Flying Tigers Memorial and Exhibition dedicated to Chennault and his aviators. It's opposite the former residence of General Stilwell.

Film portrayal

In the 1945 US propaganda film God Is My Co-Pilot, Chennault as commander of the AVG was played by the Canadian Raymond Massey.

Awards and decorations

- Army Distinguished Service Medal with oak leaf cluster

- Navy Distinguished Service Medal

- Legion of Merit

- Distinguished Flying Cross

- Air Medal

- Victory Medal

- Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with four campaign stars

- World War II Victory Medal

- Order of Blue Sky and White Sun (China)

- Order of the Cloud and Banner, 3rd Grade (China)

- Commander, Order of the British Empire (United Kingdom)

- Legion of Honor (France)

- Order of Polonia Restituta (Poland)

- Croix de Guerre (France)

- China War Memorial Medal (China)

In addition to the above, Chennault received several other foreign orders and decorations.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ The family name is French. Claire Lee Chennault is a French-American by ancestry. He is in the genealogy book: Descendants of Estienne Chennault who came to the U.S. in the 1800s.[1]

- ↑ "AVG fighter aircraft came from a Curtiss assembly line producing Tomahawk IIB models for the Royal Air Force in North Africa. The Tomahawk IIB was similar to the U.S. Army's earlier P-40B model, and there is some evidence that Curtiss actually used leftover components from that model in building the fighters intended for China. The fighters were purchased without "government-furnished equipment" such as reflector gunsights, radios and wing guns; the lack of these items caused continual difficulties for the AVG in Burma and China.

- ↑ The official Army history notes that 23 July 1941 FDR "approved a Joint Board paper which recommended that the United States equip, man, and maintain the 500-plane Chinese Air Force proposed by Currie. The paper suggested this force embark on a vigorous program to be climaxed by the bombing of Japan in November 1941.Lauchlin Currie was the White House official dealing with China.[19]

Citations

- ↑ "Profile: Chenault, Claire Lee." chenault.org. Retrieved: September 7, 2010.

- ↑ "Chenault profile." infoplease.com. Retrieved: October 5, 2011.

- ↑ "United States Census, 1940: Claire Chennault." familysearch.org. Retrieved: July 19, 2015.

- ↑ Hessen 1983, p. ix.

- ↑ Byrd 1987, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Allen, p. 64

- ↑ "Claire Lee Chennault and the Flying Tigers", vac.gov.tw; retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ↑ Byrd 1987, Chapter 3.

- ↑ Owen 1985

- ↑ Byrd 1987, Chapter 6.

- ↑ Byrd 1987, Chapter 7.

- ↑ Xu, Guangqiu. War Wings: The United States and Chinese Military Aviation, 1929–1949. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001. ISBN 978-0-313-32004-0.

- ↑ "The Flying Tigers American Volunteer Group – Chinese Air Force." flyingtigersavg.22web.net. Retrieved: May 20, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Byrd 1987, Chapter 8.

- ↑ Byrd 1987, Chapters 7–8.

- ↑ Dr. T.V. Soong: President of the Bank of China.

- ↑ Schultz 1987

- ↑ Sehnert, Walt. "McCook's Glen Beneda and the Flying Tigers." mccookgazette.com, January 5, 2009. Retrieved: May 22, 2009.

- 1 2 Romanus, Charles F. and Riley Sunderland. "China-Burma-India Theater: Stillwell's Mission to China." U.S. Army in World War II, 1953, p. 23. Retrieved: September 17, 2014.

- ↑ Schaller, Michael. "American Air Strategy in China, 1939-1941: The Origins of Clandestine Air Warfare". American Quarterly(JSTOR), Edition 28, issue 1, 1976. pp. 3-19.

- ↑ Alan Armstrong, Preemptive Strike: The Secret Plan That Would Have Prevented the Attack on Pearl Harbor (2006) is a popular version.

- ↑ "Burma Road Air Defense Scores." Associated Press, Chungking, December 20, 1941.

- ↑ "'Crazy' Maneuver Used by Colonel", Associated Press, New Orleans, December 20, 1941.

- ↑ "Domei Says Japs Downed Five Ships", Associated Press, Tokyo, December 20, 1941.

- ↑ "American Fliers Engage Japanese", Associated Press, Chungking, December 20, 1941.

- ↑ Considine, Bob. "Under Fire." theaerodrome.com, October 18, 2007. Retrieved: February 11, 2010.

- ↑ "Time cover (December 6, 1943)." time.com. Retrieved: September 17, 2014.

- 1 2 Smith 1995

- ↑ Chennault, Claire Lee (Major-General, retired). Testimony to the Senate Joint Committee on the Armed Forces and Foreign Relations, letter dated June 20, 1951, and supplemental statement, Appendix 00, p. 3342.

- ↑ Byrd 1987, p. 367.

- ↑ "Military Figures: General Chennault." rlingtonCemetery.org. Retrieved: December 2, 2009.

- 1 2 "Lt. Col. Claire Patterson Chennault." Natchez Democrat, October 5, 2011. Retrieved: October 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Rosemary Chennault Simrall." Monroe News-Star. Retrieved: August 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Descendants of Claire Lee Chennault." familytreemaker.genealogy.com, June 7, 2010.

- ↑ Rosholt, Malcolm, Jack Gadberry and Myron D. Levy. "Chennault Enshrined in Aviation Hall of Fame". Flying Tiger, 1973.

- ↑ "U.S. #2187 40¢ Claire Chennault Great Americans Series." Mystic Stamp Company Catalog. Retrieved: March 25, 2013.

- ↑ "Great American Stamp Honors Gen. Chennault." The Times-News, Hendersonville, North Carolina, September 9, 1990. Retrieved: March 25, 2013.

- ↑ "Services for last son of Gen. Claire Chennault." goerie.com. Retrieved: July 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Chennault Aviation and Military Museum Director Nell Calloway." flickr.com. Retrieved: July 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Former U.S. President James Carter attends peace festival in central China." Xinhuanet.com, September 8, 2010. Retrieved: September 8, 2010.

Bibliography

- Armstrong, Alan. Preemptive Strike: The Secret Plan That Would Have Prevented the Attack on Pearl Harbor. Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1-5922-8913-4.

- Allen, Ernest, and Kilbourne Historical Society. A History of Early Kilbourne, Louisiana, West Carroll Parish. Louisiana, Kilbourne. Ernest Allen publisher, 2006.

- Bond, Janet. A Pictorial History of China Post 1, Part I – 1919–1959. Slidell, Louisiana: American Legion Generals Ward & Chennault & Lt. Helseth Post No. 1 (China), 1988.

- Byrd, Martha. Chennault: Giving Wings to the Tiger. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University Alabama Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8173-0322-7.

- Caidin, Martin. The Ragged, Rugged Warriors. New York: Ballantine, 1978. ISBN 0-345-28302-3.

- Chennault, Claire. Way of a Fighter. New York: Putnam's, 1949.

- "Claire Lee Chennault", Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement 6: 1956–1960, Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Thomson Gale, 1980.

- Ford, Daniel. Flying Tigers: Claire Chennault and His American Volunteers, 1941–1942. Washington, DC: HarperCollins|Smithsonian Books, 2007. ISBN 0-06-124655-7.

- Hessen, Robert, ed. General Claire Lee Chennault: A Guide to His Papers in the Hoover Institution Archives. Palo Alto, California: Hoover Institution Press, 1983. ISBN 0-8179-2652-6.

- Latimer, Jon. Burma: The Forgotten War. London: John Murray, 2004. ISBN 0-7195-6576-6.

- Leary, William M. "Chennault, Claire Lee" in American National Biography Online 2000

- "1900 United States Federal Census, Franklin Parish, Louisiana, Ward 2." Ancestry.com, January 20, 2007.

- Owen, Stephen. The Flying Key Brothers and Their Flight To Remember. Spartanburg, South Carolina: Southeastern Printing, 1985. ISBN 0-9614830-0-8.

- Samson, Jack. The Flying Tiger. The Lyons Press, 1987. ISBN 1-59228-711-5.

- Schaller, Michael. "American Air Strategy in China, 1939-1941: The Origins of Clandestine Air Warfare," American Quarterly (1976) 28#1 pp. 3–19 in JSTOR

- Schultz, Duane. The Maverick War: Chennault and the Flying Tigers. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0-31200-618-1.

- Scott, Robert Lee Jr. Flying Tiger: Chennault of China. Westport Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1973. ISBN 0-8371-6774-4.

- Smith, Felix. China Pilot: Flying for Chiang and Chennault. New York: Brassey's Inc., 1995. ISBN 978-1-57488-051-9.

- Smith, William M. Jr. "The Making of a Hero." North Louisiana History Vol. 19, Nos. 2–3, Spring-Summer 1988, pp. 51–66.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Claire Lee Chennault. |

- Flying Tigers Memorial in China (in Chinese)

- Short biography of Chennault

- Biographical sketch at USAF Museum at the Wayback Machine (archived July 18, 2006)

- Chennault at Arlington Cemetery

- Time magazine, 1942 article on Chennault

- Claire Lee Chennault papers at the Hoover Institution Archives

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Franklin D. Roosevelt |

Cover of Time Magazine December 6, 1943 |

Succeeded by Charles Edward Wilson |