Cleveland Hall, London

| Cleveland Hall | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Type | Meeting hall |

| Address | 54 Cleveland Street |

| Town or city | London |

| Country | England |

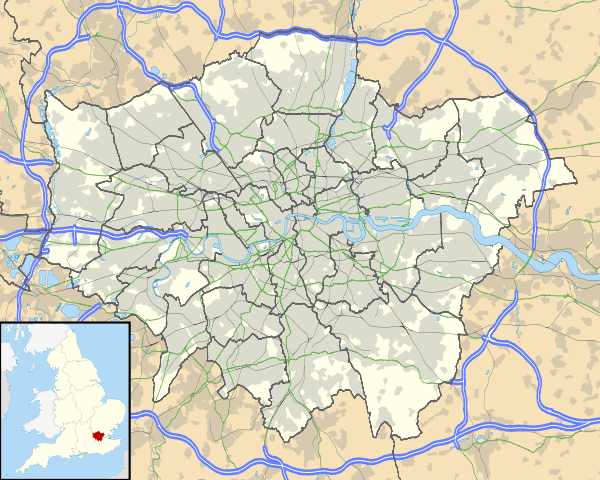

| Coordinates | 51°31′14″N 0°08′20″W / 51.520574°N 0.138792°WCoordinates: 51°31′14″N 0°08′20″W / 51.520574°N 0.138792°W |

| Completed | 1861 |

Cleveland Hall was a meeting hall in Cleveland Street, London that was a center of the British secularist movement between 1861 and 1878, and that was then used for various purposes before becoming a Methodist meeting hall.

Building and location

Cleveland Hall was built with a legacy from William Devonshire Saull, an Owenite, and in 1861 replaced the John Street Institution as the London center of freethought. The hall was controlled by its shareholders, and these changed over time, so it was not always used for freethought purposes.[1]

The hall was at 54 Cleveland Street, Marylebone, north of Soho in an area with a large immigrant population.[2] According to the Secular Review and Secularist in 1877 the hall was a large and commodious building with a historic repute in connection with secular propaganda. It was near Fitzroy Square, three minutes walk from the buses of Tottenham Court Road or from Portland Road Station.[3] Another source described the location less kindly as in "Cleveland Street, a street lying in that mass of pauperism at the rear of Tottenham Court Road Chapel".[4]

Secularism center

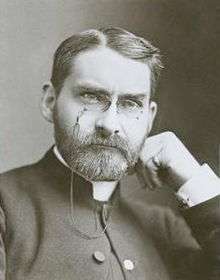

In the 1860s several lecturers including George Holyoake and Harriet Law who rejected the leadership of Charles Bradlaugh tried to make the hall a rival to his Hall of Science.[1] George William Foote in his Reminiscences of Charles Bradlaugh recalls coming to London in January 1868 with "plenty of health and very little religion". He was taken to Cleveland Hall by a friend, and "heard Mrs. Law knock the Bible about delightfully. She was not what would be called a woman of culture, but she had what some devotees of 'culchaw' do not posses—a great deal of natural ability..."[5] A few weeks later Foote heard Bradlaugh speaking at the hall. Foote later became increasingly involved in the secular movement.[6]

An 1870 book on The Religious Life of London described Cleveland Hall as the headquarters of the Secularists. The doors would open at seven and the lectures would start at 7:30. There was a fee to enter, and an additional fee for seats near the front.[4] The room was generally "half full of respectable and sharp working men, all very positive and enthusiastic.[7]

Some sample lectures were Charles Watts on An Impartial Estimate of the Life and Teachings of the Founder of Christianity; Bradlaugh on Capital and Labour, and Trades' Unions; Harriet Law on The Teachings and Philosophy of J.S. Mill, Esq., The Late Robert Owen: a Tribute to His Memory and an Appeal to Women to Consider their Interests in Connection with the Social, Political and Theological Aspects of the Times. Each lecture would be followed by an open discussion.[8] In 1869 The Gospel Magazine reported that "with feelings of revulsion, we witnessed at Cleveland Hall the reception of an infant into the Atheistic body. Its mistaken mother publicly placed the child in the arms of the notorious lecturer, Mr. Bradlaugh, who bestowed upon it his Atheistic blessing..." The writer concluded that these events "clearly portend the near approach of the period when the terrible conflict which is pointed to in so many prophetic portions of the Scriptures will take place."[9]

The secularists let others make use of the hall. For a year from November 1865 the hall was leased for Sunday evenings so that the American Unitarian abolitionist Moncure Daniel Conway could "address the working classes." However, the audience consisted of well-dressed lower-middle-class people.[10] In April 1868 there was a meeting of operative house-painters to discuss co-operation with the Manchester Alliance of Painters on a federative principle.[11] In September 1868 the Artisans' Club and Trades' Hall Company held a meeting seeking funding for a hall for the use of trade, benefit and other societies.[12]

Mixed uses

In 1869 the ownership of the hall changed.[1] In 1870 the Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle noted that the Reverend Charles Adolphus Row was delivering a course of lectures in defence of the gospel at Cleveland Hall, Fitzroy square, the former secularist center.[13]

On 25 June 1871 the spiritualist Mrs. Emma Hardinge Britten delivered a lecture at Cleveland Hall while under inspiration of a spirit, in which she described the third and higher spheres.[14] On 16 April 1874 the British National Association of Spiritualists held a grand inaugural soirée in Cleveland Hall.[15] On 10 May 1874 Cora L.V. Tappan delivered an inspirational discourse at the Hall.[16] The next week Judge John W. Edmonds delivered an address to a large audience there through Mrs. Tappan as medium; the judge had died less than two months earlier.[17] Charles Maurice Davies wrote that year,

The reigning favourite at present in London is Mrs. Cora Tappan, who was better known as a medium in America by her maiden name of Cora Hatch. She came out with considerable éclat at St. George's Hall, after which she drifted to Weston's Music Hall in Holborn, in which slightly incongruous locality she set up her "Spiritual Church". Now she has abandoned the ecclesiastical title, and hangs out at Cleveland Hall, somewhere down a slum by Fitzroy Square. Facilis descensus!"[18]

On 18 August 1874 Jonathan Charles King of 54 Cleveland Street and 30 Howland Street, proprietor of the Cleveland Hall Assembly Rooms, initiated proceedings for liquidation under the Bankruptcy Act.[19]In 1876 Harriet Law again leased the hall for use in freethought lectures.[1]In July 1877 it was reported that Harriet Law had leased Cleveland Hall for another twelve months, and a meeting would be held at which George Holyoake, Harriet Law, George William Foote and others would speak.[3] The secularists did not renew the lease in 1878.[1] The hall was then used for some years for dances and other purposes.[20]

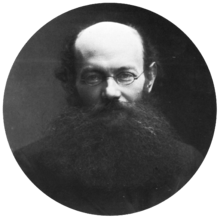

In the 1870s and 1880s various groups of political refugees came to London, including French communards, German socialists, Russian Jews and Italian anarchists such as Tito Zanardelli.[21] Most of the Italian refugees settled in Soho and Clerkenwell. Giovanni Defendi, who had fought with Garibaldi, lived at 17 Cleveland Street.[22] On 18 July 1881 an anarchist congress was held at the Cleveland Hall, Fitzroy Square, at which the American Marie Le Compte, Louise Michel, and Prince Peter Kropotkin spoke.[23] The congress openly supported "propaganda by deed", and discussed using of "chemical materials" to further the revolution.[24] The meeting resulted in a question being asked in the House of Commons.[25]

The Commonweal of 5 February 1887 announced that "A meeting of the international revolutionists to protest against the Coming War will be held in Cleveland Hall, Cleveland Street... The chair will be taken by comrade [William] Morris. Speeches will be made in various languages ..."[2] Morris described the place at the time of the meeting as "a wretched place, once flash and now sordid, in a miserable street which illustrates this genius for complexity and frustration. It was the headquarters of the orthodox Anarchists, most of the foreign speakers belonging to this persuasion; but a Collectivist also spoke, and one, at least, from the Autonomy section who have some quarrel which I can't understand with the Cleveland Hall people."[26]

Methodist mission

The hall came to be owned by the West London Methodist Mission of Hugh Price Hughes.[1] The foundation, which was active from 1889 to 1916, was dedicated to helping poor young women.[29] The mission spent £1,500 to convert it into a mission hall.[20] There was seating accommodation for six hundred people upstairs, and downstairs had rooms for the same number of people and a kitchen. The hall was fronted by a three-story building that now held a coffee-palace, classrooms and a place of residence.[30]

The Hall was reopened in May 1890. Meetings were held every night.[20] An American visitor who attended the opening of the hall said the meeting was protracted and many souls were converted.[31] In 1890 the hall was said to be self-supporting.[30] In practice, however, it relied on generous donations.[32] A dedication service for the Cleveland Hall Food Depot was held in February 1891. The depot received and distributed gifts of food for the hungry.[32]

The mission held coffee concerts, lantern talks and a social hour for young men and women after the Sunday evening service, as well as many other activities.[32] Clara Sophia [Mary] Neal ran a club for working girls at Cleveland Hall two or three evenings a week. She said,

No words can express the passionate longing which I have to bring some of the beautiful things of life within easy reach of the girls who earn their living by the sweat of their brow... If these Clubs are up to the ideal which we have in view, they will be living schools for working women, who will be instrumental in the near future, in altering the conditions of the class they represent.[33]

The Girls' Club was a great success, but in the fall of 1895 Mary and Emmeline Pethick left the mission to set up their own Espérance Club for girls. They wanted to escape from the mission's institutional constraints and to experiment with dance and drama.[34] The last records of the West London Mission from Cleveland Hall date to 1916.[29]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Royle 1980, p. 47.

- 1 2 Boos 2013.

- 1 2 The Agnostic Journal and Eclectic Review 1877, p. 76.

- 1 2 Ritchie 1870, p. 376.

- ↑ Foote 1891, p. 5.

- ↑ Foote 1891, p. 6.

- ↑ Ritchie 1870, p. 378.

- ↑ Ritchie 1870, p. 377.

- ↑ Grant 1869, p. 334.

- ↑ Conway 2012, p. 48.

- ↑ Building News and Engineering Journal 1868, p. 236.

- ↑ Building News and Engineering Journal 1868, p. 677.

- ↑ Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1870, p. 243.

- ↑ Crowell 1881, p. 257.

- ↑ Houghton 1882, p. 172.

- ↑ Edmonds & Richmond 1875, p. 17.

- ↑ Crowell 1881, p. 339.

- ↑ Davies 1874, p. 43.

- ↑ Watson 1874, p. 4098.

- 1 2 3 Smiley 1890, p. 214.

- ↑ Dipaola 2004, p. 38.

- ↑ Dipaola 2004, p. 46.

- ↑ Young 2011.

- ↑ Dipaola 2004, p. 51.

- ↑ Great Britain. Parliament 1881, p. 1461.

- ↑ Gaunt 1942, p. 200.

- ↑ Pentelow 2002, p. 42.

- ↑ Pentelow 2002, p. 126.

- 1 2 Cleveland Hall, Cleveland Street: Archives.

- 1 2 Dickson 1890, p. 214.

- ↑ Groome 1891, p. 315.

- 1 2 3 Rose 1986, p. 143.

- ↑ Judge 1989, p. 547.

- ↑ Judge 1989, p. 548.

Sources

- Boos, Florence (2013). "William Morris's Socialist Diary". Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Building News and Engineering Journal. Office for Publication and advertisements. 1868. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- "Cleveland Hall, Cleveland Street". London Metropolitan Archives. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Conway, Moncure Daniel (7 June 2012). Autobiography: Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-05061-6. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- Crowell, Eugene (1881). The Identity of Primitive Christianity and Modern Spiritualism. G. W. Carleton & Company. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- Davies, Charles Maurice (1874). Heterodox London: Or, Phases of Free Thought in the Metropolis. Tinsley Brothers. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- Dipaola, Pietro (April 2004). "The 1880s and the International Revolutionary Socialist Congress". Italian Anarchists in London (PDF). Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Dickson, William A. (1890). "Aggressive Movement in British Methodism". The Methodist Review. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Edmonds, John Worth; Richmond, Cora Linn V. (1875). Letters and tracts on spiritualism. Also, two inspirational orations by C. L. V. Tappan. Ed. by J. Burns. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle. 1870. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- Foote, George William (1891). Reminiscences of Charles Bradlaugh. Progressive Publishing Company. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- Gaunt, William (1942). The Pre-raphaelite Tragedy. University Microfilms. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Grant, James (1869). "The Religious Tendencies of the Times: or, How to deal with the Deadly Errors and dangerous Delusions of the Day". The Gospel magazine, and theological review. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- Great Britain. Parliament (1881). Hansard's Parliamentary Debates. Hansard. p. 1461. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- Groome, P. L. (1891). Rambles of a southerner in three continents. . Thomas brothers, printers. p. 315. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Houghton, Georgiana (1882). Evenings at home in spiritual séance. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- Judge, Roy (1989). "Mary Neal and the Espérance Morris" (PDF). Folk Music Journal. 5 (5). Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Pentelow, Mike; Rowe, Marsha (2002). Characters of Fitzrovia. Random House. ISBN 0712680152.

- Ritchie, James Ewing (1870). The Religious Life of London. Tinsley Brothers. p. 376. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- Rose, E. Alan (May 1986). "Hugh Price Hughes and the West London Mission" (PDF). Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society. XLV. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Royle, Edward (1980). Radicals, Secularists, and Republicans: Popular Freethought in Britain, 1866–1915. Manchester University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-7190-0783-5. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- Smiley, Francis Edward (1890). The Evangelization of a Great City: Or, The Churches' Answer to the Bitter Cry of Outcast London. Sunshine Publishing Company. p. 214. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- "Secularism in West London". The Agnostic Journal and Eclectic Review. W. Stewart. 1877. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- Watson, J.G. (18 August 1874). "Proceedings for Liquidation by Arrangement or Composition with Creditors, instituted by Jonathan Charles King..." (PDF). Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Young, Sarah J. (2011). "Russians in London: Pyotr Kropotkin". Retrieved 27 August 2013.