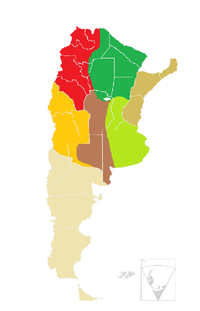

Climatic regions of Argentina

Due to its vast size and range of altitudes, Argentina possesses a wide variety of climatic regions, ranging from the hot subtropical region in the north to the cold subantarctic in the far south. Lying between those is the Pampas region, featuring a mild and humid climate. Many regions have different, often contrasting, microclimates. In general, Argentina has four main climate types: warm, moderate, arid, and cold in which the relief features, and the latitudinal extent of the country, determine the different varieties within the main climate types.

Northern parts of the country[note 2] are characterized by hot, humid summers with mild, drier winters, and highly seasonal precipitation. Mesopotamia, located in northeast Argentina, has a subtropical climate with no dry season and is characterized by high temperatures and abundant rainfall because of exposure to moist easterly winds from the Atlantic Ocean throughout the year. The Chaco region in the center-north, despite being relatively homogeneous in terms of precipitation and temperature, is the warmest region in Argentina, and one of the few natural areas in the world located between tropical and temperate latitudes that is not a desert. Precipitation decreases from east to west in the Chaco region because eastern areas are more influenced by moist air from the Atlantic Ocean than the west, resulting in the vegetation transitioning from forests and marshes to shrubs. Northwest Argentina is predominantly dry, hot, and subtropical although its rugged topography results in a diverse climate.

Central Argentina, which includes the Pampas to the east, and the Cuyo region to the west, has a temperate climate with hot summers and cool, drier winters. In the Cuyo region, the Andes obstruct the path of rain-bearing clouds from the Pacific Ocean; moreover, its latitude coincides with the subtropical high. Both factors render the region dry. With a wide range of altitudes, the Cuyo region is climatically diverse, with icy conditions persisting at altitudes higher than 4,000 m (13,000 ft). The Pampas is mostly flat and receives more precipitation, averaging 500 mm (20 in) in the western parts to 1,200 mm (47 in) in the eastern parts. The weather in the Pampas is variable due to the contrasting air masses and frontal storms that impact the region. These can generate thunderstorms with intense hailstorms and precipitation, and are known to have the most frequent lightning, and highest convective cloud tops, in the world.

Patagonia, in the south, is mostly arid or semi–arid except in the extreme west where abundant precipitation supports dense forest coverage, glaciers, and permanent snowfields. Its climate is classified as temperate to cool temperate with the surrounding oceans moderating temperatures on the coast. Away from the coast, areas on the plateaus have large daily and annual temperature ranges. The influence of the Andes, in conjunction with general circulation patterns, generates one of the strongest precipitation gradients (rate of change in mean annual precipitation in relation to a particular location) in the world, decreasing rapidly to the east. In much of Patagonia precipitation is concentrated in winter with snowfalloccurring occasionally, particularly in the mountainous west and south; precipitation is more evenly distributed in the east and south. One defining characteristic is the strong winds from the west which blow year-round, lowering the perception of temperature (wind chill), while being a factor in keeping the region arid by favouring evaporation.

Definition of the regions

The vast size, and wide range of altitudes, contribute to Argentina's diverse climate.[2] Consequently, there is a wide variety of biomes in the country, including subtropical rain forests, semi-arid and arid regions, temperate plains in the Pampas, and cold subantarctic in the south.[3] In general, Argentina has four main climate types: warm, moderate, arid, and cold in which the relief features, and the latitudinal extent of the country, determine the different varieties in the main climate types.[4] Despite the diversity of biomes, about two-thirds of Argentina is arid or semi-arid.[3][5] Argentina is best divided into six distinct regions reflecting the climatic conditions of the country as a whole.[6] From north to south, these regions are Northwest, Chaco, Northeast, Cuyo/Monte, Pampas, and Patagonia.[6][7] Each climatic region has distinctive types of vegetation.[8]

Mesopotamia

The region of Mesopotamia includes the provinces of Misiones, Entre Ríos and Corrientes.[9] It lies between the Uruguay and Paraná rivers, which serve as natural borders for the region.[2][7]

It has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa according to the Köppen climate classification).[9] whose main features are high temperatures and abundant rainfall throughout the year.[4] This year-round rainfall occurs because most of the region lies north of the subtropical high pressure belt even in winter, exposing it to moist easterly winds from the Atlantic Ocean throughout the year.[10]:12 Water deficiencies and extended periods of drought are uncommon, and much of the region has a positive water balance (i.e. the precipitation exceeds the potential evapotranspiration).[9][11][12]:85

Precipitation

Mesopotamia is the wettest region in Argentina[13] with average annual precipitation ranges from less than 1,000 mm (39 in) in the southern parts, to approximately 1,800 mm (71 in) in the eastern parts.[9][12]:31Precipitation is slightly higher in summer than in winter, and generally decreases from east to west and from north to south.[12]:32[14] Summer (December–February) is the most humid season, with precipitation ranging from 300 to 450 mm (12 to 18 in).[12]:37 Fall (March–May) is the rainiest season, with many places receiving over 350 mm (14 in).[12]:38 Most of the rainfall during summer and fall is caused by convective thunderstorms.[12]:38–39 Winter (June–August) is the driest season, with a mean precipitation of 110 mm (4.3 in) throughout the region.[12]:39 Most of the winter precipitation is the result of synoptic scale, low pressure weather systems (large scale storms such as extratropical cyclones),[12]:40 particularly the sudestada, which often bring long periods of precipitation, cloudiness, cooler temperatures, and strong winds.[14][15][16][17] Snowfall is extremely rare and mainly confined to the uplands of Misiones Province where the last significant snowfall occurred in 1975 in Bernardo de Irigoyen.[18][19] Spring (September–November) is similar to fall with a mean precipitation of 340 mm (13 in).[12]:40

Temperatures

Mean annual temperatures range from 17 °C (63 °F) in the south to 21 °C (70 °F) in the north.[13] Summers are hot and humid while winters are mild.[9][10]:12[14] The mean January temperature throughout most of the region is 25 °C (77 °F) except in the uplands of Misiones Province where they are lower owing to its higher elevation.[13] During heat waves, temperatures can exceed 40 °C (104 °F) in the summer months, while in the winter months, cold air masses from the south can push temperatures below freezing, causing frost.[15][16][18] However, such cold fronts are brief, and are less intense than in areas further south or at higher altitudes.[15][16][18]

Statistics for selected locations

| Climate data for Posadas, Misiones | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32.7 (90.9) |

32.0 (89.6) |

30.7 (87.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

21.6 (70.9) |

22.2 (72) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.0 (77) |

28.1 (82.6) |

29.8 (85.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

27.4 (81.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.1 (70) |

20.9 (69.6) |

19.5 (67.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

11.2 (52.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.9 (60.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

20.0 (68) |

16.1 (61) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 156.4 (6.157) |

157.3 (6.193) |

142.5 (5.61) |

154.8 (6.094) |

140.5 (5.531) |

131.6 (5.181) |

103.6 (4.079) |

111.9 (4.406) |

141.0 (5.551) |

177.7 (6.996) |

156.5 (6.161) |

150.9 (5.941) |

1,724.7 (67.902) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 79 | 80 | 77 | 74 | 73 | 71 | 69 | 69 | 74 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 198.4 | 192.1 | 186.0 | 168.0 | 167.4 | 129.0 | 158.1 | 170.5 | 147.0 | 176.7 | 183.0 | 195.3 | 2,071.5 |

| Source #1: NOAA[20] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun, 1978–2014)[21] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Paraná, Entre Ríos | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 31.3 (88.3) |

30.1 (86.2) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

17.2 (63) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.1 (70) |

24.2 (75.6) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.8 (85.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 18.6 (65.5) |

17.8 (64) |

16.1 (61) |

12.7 (54.9) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.1 (44.8) |

6.8 (44.2) |

7.3 (45.1) |

8.9 (48) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

12.4 (54.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 126.3 (4.972) |

127.0 (5) |

155.9 (6.138) |

101.6 (4) |

51.6 (2.031) |

34.0 (1.339) |

33.6 (1.323) |

35.6 (1.402) |

69.1 (2.72) |

106.4 (4.189) |

115.1 (4.531) |

112.9 (4.445) |

1,069.1 (42.091) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 65 | 70 | 75 | 78 | 80 | 80 | 79 | 74 | 71 | 70 | 68 | 65 | 73 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 291.4 | 249.2 | 238.7 | 213.0 | 189.1 | 156.0 | 170.5 | 201.5 | 207.0 | 251.1 | 273.0 | 272.8 | 2,713.3 |

| Source: NOAA[22] | |||||||||||||

Chaco

The Chaco region in the center-north completely includes the provinces of Chaco, and Formosa.[23] Eastern parts of Jujuy Province, Salta Province, and Tucumán Province, and northern parts of Córdoba Province and Santa Fe Province are part of the region.[23] As well, most of Santiago del Estero Province lies within the region.[24]

The region has a subtropical climate.[14][25] Under the Köppen climate classification, western parts have a semi-arid climate (Bs)[9] while the east has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa).[26][27]:486 Chaco is one of the few natural regions in the world located between tropical and temperate latitudes that is not a desert.[27]:486 Precipitation and temperature are relatively homogeneous throughout the region.[27]:486 The general atmospheric circulation influences the climate of the region, primarily by two permanent high pressure systems - the South Pacific High and the South Atlantic High - and a low pressure system that develops over northeast Argentina called the Chaco Low.[26] The interaction between the South Atlantic High and the Chaco Low generates a pressure gradient that brings moist air from the east and northeast to eastern coastal and central regions of Argentina.[10][28] In summer, this interaction strengthens, favouring the development of convective thunderstorms that can result in heavy rainfall.[10][28] In contrast, winters are dry due to these systems weakening, and the lower insolation that weakens the Chaco Low, and the northward displacement of westerly winds.[28][29] During the entire year, the South Pacific High influences the climate by bringing cold, moist air masses originating in Patagonia[30] leading to cold temperatures and frost, particularly during winter.[29] Summers feature more stable weather than winter since the South Atlantic and South Pacific highs are at their southernmost positions, making the entrance of cold fronts more difficult.[9][29]

Precipitation

Mean annual precipitation ranges from 1,200 mm (47 in) in the eastern parts of Formosa Province to a low of 450 to 500 mm (18 to 20 in) in the west and southwest.[9][12]:30 Most of the precipitation is concentrated in the summer and decreases from east to west.[9][14] Summer rains are intense, and torrential rain is common, occasionally causing floods and soil erosion.[26][31] During the winter months, precipitation is sparse.[9][14] Eastern areas receive more precipitation than western areas since they are more influenced by moist air from the Atlantic Ocean. This penetrates the eastern areas more than the west, bringing it more precipitation.[9] As a result, the vegetation differs with eastern areas being covered by forests, savannas, marshes, and subtropical wet forest, while western areas are dominated by medium and low forests of mesophytic and xerophytic trees, and a dense understory of shrubs and grasses.[3] The western part has a pronounced dry winter season while the eastern parts have a slightly drier season.[31] In all parts of the region, precipitation is highly variable from year to year.[30] The eastern part of the region receives just enough precipitation to have a positive water balance.[26] By contrast, the western parts of the region have a negative water balance (the potential evapotranspiration exceeds the precipitation) owing to lower precipitation.[12]:85

Temperatures

The Chaco region is the hottest in Argentina, with a mean annual temperature of 23 °C (73 °F).[9] With mean summer temperatures reaching 28 °C (82 °F), the region has the hottest summers in the country.[9][12]:63 Winters are mild and brief, with mean temperatures in July ranging from 16 °C (61 °F) in the northern parts to 14 °C (57 °F) in the southernmost parts.[32]:1 Absolute maximum temperatures can reach up to 49 °C (120 °F) while during cold waves, temperatures can fall to −6 °C (21 °F).[9] Eastern areas are more strongly influenced by maritime climate than western areas, leading to a smaller thermal amplitude (difference between average high and average low temperatures).[26] This results in absolute maximum and minimum temperatures being 43 °C (109 °F) and −2.5 °C (27.5 °F) in the east compared to more than 47 °C (117 °F) and −7.2 °C (19.0 °F) in the west.[31]

Statistics for selected locations

| Climate data for Rivadavia, Salta (located in the west) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 35.8 (96.4) |

34.4 (93.9) |

32.4 (90.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

22.7 (72.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

29.7 (85.5) |

33.2 (91.8) |

34.4 (93.9) |

35.5 (95.9) |

30.3 (86.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22.1 (71.8) |

21.5 (70.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

17.2 (63) |

14.2 (57.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.0 (68) |

21.4 (70.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 128.1 (5.043) |

97.7 (3.846) |

91.3 (3.594) |

64.4 (2.535) |

16.7 (0.657) |

10.9 (0.429) |

4.4 (0.173) |

4.1 (0.161) |

13.6 (0.535) |

42.9 (1.689) |

76.6 (3.016) |

115.3 (4.539) |

666.0 (26.22) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 61 | 64 | 68 | 70 | 70 | 68 | 62 | 54 | 52 | 56 | 50 | 59 | 61 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 248 | 254 | 248 | 180 | 186 | 120 | 155 | 217 | 210 | 248 | 240 | 248 | 2,554 |

| Source #1: NOAA[33] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun and humidity)[34] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Formosa, Argentina (located in the east) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 33.4 (92.1) |

32.9 (91.2) |

31.4 (88.5) |

27.7 (81.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.8 (73) |

23.8 (74.8) |

25.7 (78.3) |

28.8 (83.8) |

30.5 (86.9) |

32.6 (90.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.9 (71.4) |

21.7 (71.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

17.3 (63.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

12.2 (54) |

12.1 (53.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.0 (62.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.8 (69.4) |

17.0 (62.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 171.2 (6.74) |

142.4 (5.606) |

151.7 (5.972) |

153.3 (6.035) |

105.6 (4.157) |

66.8 (2.63) |

49.6 (1.953) |

60.1 (2.366) |

85.1 (3.35) |

120.7 (4.752) |

171.0 (6.732) |

146.8 (5.78) |

1,424.3 (56.075) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 74 | 76 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 77 | 75 | 72 | 70 | 71 | 70 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 279.0 | 235.2 | 229.4 | 201.0 | 201.5 | 171.0 | 192.2 | 179.8 | 186.0 | 232.5 | 255.0 | 282.1 | 2,644.7 |

| Source: NOAA[35] | |||||||||||||

Northwest

Northwest Argentina consists of the provinces of Catamarca, Jujuy, La Rioja, and western parts of Salta Province, and Tucumán Province.[36] Although Santiago del Estero Province is part of northwest Argentina, much of the province lies in the Chaco region.[24]

Northwest Argentina is predominantly dry, hot, and subtropical.[37] Owing to its rugged topography, the region is climatically diverse, depending on the altitude, temperature, and distribution of precipitation.[38] Consequently, vegetation differs within these different climate types.[39] In general, the climate can be divided into two main types: a cold arid or semi-arid climate at the higher altitudes, and warmer subtropical climate in the eastern parts of the region.[37][38] Under the Köppen climate classification, the region has 5 different climate types: semi–arid (BS), arid (BW), temperate climate without a dry season and with a dry season (Cf and CW respectively), and an alpine climate at the highest altitudes.[39]

The atmospheric circulation is controlled by the two semi–permanent South Atlantic and South Pacific highs,[40]:18 and the Chaco Low.[26][41] During summer, the interaction between the South Atlantic High and the Chaco Low brings northeasterly and easterly winds that carry moisture to the region, particularly in the northern parts.[38][39][41] The movement of moist air into the region during summer results in very high precipitation.[40]:20 Most of the precipitation comes from the east since the Andes block most moisture from the Pacific Ocean.[10][38] Southern parts of the region are influenced by cold fronts travelling northward.[40]:18[41] These cold fronts are responsible for producing precipitation during summer.[40]:18 For example, in Tucumán Province, cold fronts are responsible for 70% of the rainfall in that province.[40]:18 Furthermore, the intertropical convergence zone (or doldrums) reaches the region during the summer months, leading to enhanced precipitation.[40]:18[41] During the winter months, the intertropical convergence zone, the South Pacific, and the South Atlantic highs move northward while the Chaco Low weakens, all of which results in the suppression of rain during the winter.[10][39][40]:20[42] With the Andes blocking most rain bearing clouds from the Pacific Ocean, along with atmospheric circulation patterns unfavourable for rain, this results in a dry season during winter.[10][39][40]:20[42] The Chaco Low attracts air masses from the South Pacific High, creating a dry and cold wind, particularly during winter.[41] At the highest altitudes, westerly winds from the Pacific Ocean can penetrate during the winter months, leading to snowstorms.[38]

Precipitation

Precipitation is highly seasonal and mostly concentrated in the summer months.[39][42] It is distributed irregularly owing to the country's topography although it generally decreases from east to west.[39][40]:29 As moist air reaches the eastern slopes of the mountains, it rises and cools adiabatically, leading to the formation of clouds that generate copious amounts of rain.[39] The eastern slopes of the mountains receive between 1,000 to 1,500 mm (39 to 59 in) of precipitation a year although some places receive up to 2,500 mm (98 in) of precipitation annually owing to orographic precipitation.[38][39] In the south, the orographic effect is enhanced by advancing cold fronts from the south, resulting in increased precipitation.[40]:22 The high rainfall on these first slopes creates the thick Yungas jungle that extends in a narrow strip along these ranges.[41][43]:56 During fall, the jungles are covered by fog and complete cloud cover.[43]:56 Beyond the first slopes of the Andes into the valleys, the air descends, warming adiabatically, and becoming drier than on the eastern slopes.[39] The north–south orientation of the mountains, which increase in altitude to the west,[38] and a discontinuous topography, creates valleys with regions of relatively high orographic precipitation in the west and drier regions in east.[39][40]:29

The temperate valleys, which include major cities such as Salta and Jujuy,[note 3] have an average precipitation ranging between 500 to 1,000 mm (20 to 39 in).[44] For example, in the Lerma Valley, which is surrounded by tall mountains, (only the northeastern part of the valley is surrounded by shorter mountains), precipitation ranges from 695 mm (27 in) in Salta to 1,395 mm (55 in) in San Lorenzo, just 11 km (6.8 mi) away.[40]:29 Rainfall in the temperate valleys is mainly concentrated in the summer months, often falling in short but heavy bursts.[45][46]

Valleys in the southern parts of the region are drier than valleys in the north due to the greater height of the Andes and the Sierras Pampeanas on the eastern slopes compared to the mountains in the north (ranging from 3,000 to 6,900 m (9,800 to 22,600 ft)), presenting a significant orographic barrier that blocks moist winds from the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.[40]:22–23[47]:28 These valleys receive less than 200 mm (8 in) of precipitation per year, and are characterized by sparse vegetation adapted to the arid climate.[41]

The area further west is the Puna region, a plateau with an average altitude of 3,900 m (12,800 ft) that is mostly a desert due the easterly winds being blocked by the Andes and the northwest extension of the Sierras Pampeanas.[38][40]:33[41][48] Precipitation in the Puna region averages less than 200 mm (8 in) a year while potential evapotranspiration ranges from 500 to 600 mm (20 to 24 in) a year, owing to the high insolation, strong winds, and low humidity that exacerbates the dry conditions.[3][49] This results in the Puna region having a water deficit in all months.[50]:17 The southeast parts of the Puna region are very arid receiving an average of 50 mm (2 in), while in the northeastern area, average annual precipitation ranges from 300 to 400 mm (12 to 16 in).[38][40]:34 Although easterly winds are rare in the Puna region, they bring 88%–96% of the area's precipitation.[38] Snowfall is rare, averaging less than five days of snow per year.[3][49] Due to the aridity of these mountains at high altitudes, the snowline can extend as far up as 6,000 m (20,000 ft) above sea level.[51] The El Niño–Southern Oscillation influences precipitation levels in northwest Argentina.[41][42][52] During an El Niño year, westerly flow is strengthened, while moisture content from the east is reduced resulting in a drier rainy season.[42][52] In contrast, during a La Niña year, there is enhanced easterly moisture transport, resulting in a more intense rainy season.[42][52] Nonetheless, this trend is highly variable both spatially and temporally.[42]

Temperatures

Temperatures in northwest Argentina vary by altitude.[38] The temperate valleys have a temperate climate, with mild summers, and dry and cool winters with regular frosts.[45][53]:53 The diurnal range in cities is fairly wide, particularly in the winter.[45][46] In the Yungas jungle to the east, the climate is hot and humid with temperatures that vary significantly based on latitude and altitude.[43]:56 Mean annual temperatures in the Yungas range between 14 to 26 °C (57 to 79 °F).[43]:56

The mean annual temperatures in the Quebrada de Humahuaca valley range from 12.0 to 14.1 °C (53.6 to 57.4 °F), depending on altitude.[50]:10 In the Calchaquí Valleys in Salta Province, the climate is temperate and arid with large thermal amplitudes, long summers, and a long frost free period which varies by altitude.[50]:10[54][55] In both the Quebrada de Humahuaca and Calchaquí valleys, winters are cold with frosts that can occur between March and September.[44]

In the valleys in the south in La Rioja and Catamarca Provinces, along with the southwest parts of Santiago del Estero Province, temperatures during the summer are very high averaging 26 °C (79 °F) in January, while winters are mild averaging 12 °C (54 °F).[56] Temperatures can exceed 40 °C (104 °F) during the summer, particularly in the central valley of Catamarca (Valle Central de Catamarca) and the valley of La Rioja Capital which lie at lower altitudes.[47]:28[56] During winter, cold fronts from the south bringing cold Antarctic air can cause temperatures to fall between −8 to −14 °C (18 to 7 °F) with severe frosts.[47] In contrast, the Zonda wind, which occurs more often during the winter months, can raise temperatures up to 35 °C (95 °F) with strong gusts, sometimes causing crop damage.[47]:33–34

Temperatures are much colder in the Puna region, with a mean annual temperature of less than 10 °C (50 °F) owing to its high altitude.[3] The Puna region is characterized by being cold but sunny throughout the year, with frosts that can occur in any month.[3][38][49] The diurnal range is large, with a thermal amplitude that can exceed 40 °C (72 °F) due to the low humidity and the intense sunlight throughout the year.[50]:17 Absolute maximum temperatures in the Puna region can reach up to 30 °C (86 °F) while absolute minimum temperatures can fall below −20 °C (−4 °F).[50]:16

Statistics for selected locations

| Climate data for Salar del Hombre Muerto (southwestern Puna region) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 19.6 (67.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

17.8 (64) |

12.8 (55) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.1 (44.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

16.2 (61.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

13.9 (57) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.2 (36) |

0.4 (32.7) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−8.9 (16) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

0.3 (32.5) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 31.4 (1.236) |

2.6 (0.102) |

1.6 (0.063) |

11.0 (0.433) |

1.0 (0.039) |

4.0 (0.157) |

7.5 (0.295) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

4.7 (0.185) |

63.8 (2.512) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 40.0 | 30.2 | 27.4 | 20.0 | 20.1 | 22.3 | 23.0 | 19.4 | 16.6 | 19.5 | 23.7 | 31.3 | 24.5 |

| Source: Secretaria de Mineria[57] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for La Quiaca (northeast parts of the Puna region) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

15.0 (59) |

14.9 (58.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21.1 (70) |

20.4 (68.7) |

18.5 (65.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

6.7 (44.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

2.2 (36) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

2.0 (35.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

0.9 (33.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 79.7 (3.138) |

68.0 (2.677) |

48.7 (1.917) |

9.7 (0.382) |

0.7 (0.028) |

0.7 (0.028) |

0.0 (0) |

0.7 (0.028) |

2.7 (0.106) |

16.3 (0.642) |

30.0 (1.181) |

78.0 (3.071) |

335.0 (13.189) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 67 | 66 | 63 | 51 | 37 | 33 | 31 | 32 | 38 | 48 | 57 | 64 | 49 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 263.5 | 228.8 | 269.7 | 288.0 | 297.6 | 285.0 | 297.6 | 303.8 | 291.0 | 306.9 | 303.0 | 275.9 | 3,410.8 |

| Source: Secretaria de Mineria[58] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Salta (located in Cerrillos, temperate valleys) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 27.2 (81) |

26.1 (79) |

24.9 (76.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

26.4 (79.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.9 (82.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 16.7 (62.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.4 (59.7) |

12.2 (54) |

8.2 (46.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

3.8 (38.8) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.0 (46.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.0 (60.8) |

11.1 (52) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 184.6 (7.268) |

131.5 (5.177) |

105.0 (4.134) |

26.8 (1.055) |

7.6 (0.299) |

2.3 (0.091) |

3.4 (0.134) |

3.7 (0.146) |

6.8 (0.268) |

23.7 (0.933) |

60.0 (2.362) |

132.5 (5.217) |

688.0 (27.087) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78 | 80 | 82 | 81 | 79 | 75 | 68 | 61 | 57 | 60 | 66 | 72 | 72 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 195.3 | 166.7 | 151.9 | 150.0 | 164.3 | 168.0 | 204.6 | 217.0 | 210.0 | 217.0 | 204.0 | 207.7 | 2,256.5 |

| Source: Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria[59] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for La Rioja, Argentina (lowland dry valleys) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 35.0 (95) |

33.3 (91.9) |

30.4 (86.7) |

27.2 (81) |

23.4 (74.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.1 (79) |

30.6 (87.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

35.0 (95) |

28.0 (82.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 20.7 (69.3) |

19.7 (67.5) |

17.9 (64.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

4.4 (39.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 80.1 (3.154) |

71.6 (2.819) |

54.1 (2.13) |

18.4 (0.724) |

7.4 (0.291) |

2.6 (0.102) |

3.1 (0.122) |

5.2 (0.205) |

6.5 (0.256) |

12.7 (0.5) |

43.3 (1.705) |

56.6 (2.228) |

361.6 (14.236) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 60 | 65 | 69 | 69 | 69 | 68 | 64 | 53 | 49 | 48 | 51 | 55 | 60 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 244.9 | 226.0 | 204.6 | 198.0 | 201.5 | 180.0 | 204.6 | 238.7 | 228.0 | 263.5 | 252.0 | 235.6 | 2,677.4 |

| Source #1: NOAA[60] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun, 1961–1990)[61] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for San Miguel de Tucumán (eastern parts of the region) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 31.3 (88.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

24.4 (75.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

18.2 (64.8) |

19.1 (66.4) |

22.5 (72.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

29.0 (84.2) |

29.6 (85.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

25.7 (78.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 20.2 (68.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

15.1 (59.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

7.6 (45.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 196.2 (7.724) |

158.1 (6.224) |

161.0 (6.339) |

67.2 (2.646) |

14.7 (0.579) |

14.0 (0.551) |

11.4 (0.449) |

12.4 (0.488) |

13.3 (0.524) |

47.8 (1.882) |

69.8 (2.748) |

200.4 (7.89) |

966.3 (38.043) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 77 | 83 | 84 | 81 | 80 | 74 | 66 | 63 | 62 | 70 | 73 | 74 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 229.4 | 183.6 | 186.0 | 162.0 | 167.4 | 156.0 | 195.3 | 235.6 | 192.0 | 201.5 | 216.0 | 232.5 | 2,357.3 |

| Source #1: Servicio Meteorológico Nacional[62] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: UNLP (sun only)[63] | |||||||||||||

Cuyo

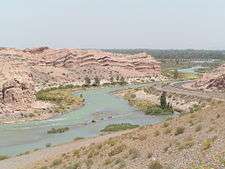

The Cuyo region includes the provinces of Mendoza, San Juan, and San Luis.[36] Western parts of La Pampa Province (as shown in map) also belong in this region, having similar climatic and soil characteristics to it.[6]

It has an arid or semi-arid climate.[64][65] The wide range in latitudes, combined with altitudes ranging from 500 m (1,600 ft) to nearly 7,000 m (23,000 ft), means that it has a variety of different climate types.[55][65] In general, most of the region has a temperate climate, with higher altitude valleys having a more milder climate.[54] At the highest altitudes (over 4,000 m (13,000 ft)), icy conditions persist year round.[65] With very low humidity, abundant sunshine throughout the year, and a temperate climate, the region is suitable for wine production.[55]

The Andes prevent rain-bearing clouds from the Pacific Ocean from moving in, while its latitude puts it in a band of the sub-tropical high pressure belt keeping the region dry.[10][64] Droughts are often frequent and prolonged.[10] The Cuyo region is influenced by the subtropical, semi–permanent South Atlantic High to the east in the Atlantic, the semi-permanent South Pacific High to the west of the Andes, and the development of the Chaco Low and westerlies in the southern parts of the region.[28][64] Most of the precipitation falls during the summer due to the stronger interaction between the Chaco Low and the South Atlantic High.[10][28]

Precipitation

Average annual precipitation ranges between 100 to 500 mm (4 to 20 in) though this varies from year to year.[64][65] More than 85% of the annual rainfall occurs from October to March, which constitutes the warm season.[64] Eastern and southeastern areas of the region receive more precipitation than western areas since they receive more summer rainfall.[28] As such, most of Mendoza and San Juan Provinces receive the lowest annual precipitation, with mean summer precipitation averaging less than 100 mm (4 in) and in rare cases, no summer rainfall.[28] Further eastward, in San Luis Province, mean summer rainfall averages around 500 mm (20 in) and can exceed 700 mm (28 in) in some areas.[28][66] Higher altitude locations receive precipitation in the form of snow during the winter months.[67][68][69] In the Cuyo region, annual precipitation is highly variable from year to year and appears to follow a cycle between dry and wet years in periods of about 2, 4–5, 6–8, and 16–22 years.[64] In wet years, easterly winds caused by the subtropical South Atlantic High are stronger, which causes more moisture to flow towards this region; during the dry years, these winds are weaker.[28][64]

Temperatures

Summers in the region are hot and generally very sunny, averaging as much as 10 hours of sunshine per day.[51][70] The average temperature in January is 24 °C (75 °F) in most of the region.[71] In contrast, winters are dry and cold and average around 7–8 hours of sunshine per day.[51][70] July temperatures range from 7 to 8 °C (45 to 47 °F).[71] Since this region has a wide range of altitudes ranging from 500 m (1,600 ft) to nearly 7,000 m (23,000 ft), temperatures can vary widely with altitude. The Sierras Pampeanas, which cross into both San Juan and San Luis Provinces, have a milder climate with mean annual temperatures ranging from 12 to 18 °C (54 to 64 °F).[69] In all locations, at altitudes over 3,800 m (12,500 ft), permafrost is present, while icy conditions persist year round at altitudes over 4,000 m (13,000 ft).[65] The region is characterized by a large diurnal range with very hot temperatures during the day followed by cold nights.[70]

The Zonda wind, a foehn wind characterized by warm, dry air can cause temperatures to exceed 30 °C (86 °F). In some cases, such as in 2003, they can exceed 45 °C (113 °F).[72][73] This wind often occurs before the passage of a cold front across Argentina, and tends to occur when a low pressure system brings heavy rain to the Chilean side, and when an upper level trough allows the winds to pass over the Andes to descend downwards.[72][74][75] As such, the temperature may rise as much as 20 °C (36 °F) in a few hours, with humidity approaching 0% during a Zonda wind event.[74] In contrast, cold waves are also common, owing to the Andes channeling cold air from the south, allowing cold fronts to come frequently during the winter months, causing cool to cold temperatures with temperatures that can fall below freezing.[75][76] Temperatures can dip below −10 to −30 °C (14 to −22 °F) at the higher altitudes.[68]

Statistics for selected locations

| Climate data for Mendoza Airport | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32.2 (90) |

30.6 (87.1) |

27.3 (81.1) |

23.5 (74.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.3 (59.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

25.5 (77.9) |

29.0 (84.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

24.1 (75.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 18.1 (64.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

5.6 (42.1) |

2.0 (35.6) |

1.7 (35.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

10.8 (51.4) |

14.3 (57.7) |

17.2 (63) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 36.4 (1.433) |

34.1 (1.343) |

27.3 (1.075) |

12.7 (0.5) |

5.9 (0.232) |

4.1 (0.161) |

6.7 (0.264) |

3.3 (0.13) |

7.8 (0.307) |

11.1 (0.437) |

15.9 (0.626) |

24.4 (0.961) |

189.7 (7.469) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 50 | 55 | 63 | 67 | 67 | 66 | 64 | 54 | 50 | 47 | 45 | 47 | 56 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 297.6 | 257.6 | 235.6 | 219.0 | 195.3 | 168.0 | 182.9 | 229.4 | 225.0 | 282.1 | 294.0 | 285.2 | 2,871.7 |

| Source: NOAA[77] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for San Luis, Argentina (in the east) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 31.1 (88) |

30.0 (86) |

27.0 (80.6) |

23.6 (74.5) |

20.3 (68.5) |

16.9 (62.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.4 (86.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

7.5 (45.5) |

4.0 (39.2) |

3.5 (38.3) |

5.3 (41.5) |

7.8 (46) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.8 (62.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 109.7 (4.319) |

86.9 (3.421) |

91.2 (3.591) |

42.2 (1.661) |

11.6 (0.457) |

8.9 (0.35) |

10.8 (0.425) |

8.1 (0.319) |

19.2 (0.756) |

35.9 (1.413) |

77.4 (3.047) |

101.3 (3.988) |

603.2 (23.748) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 55 | 56 | 63 | 65 | 64 | 62 | 60 | 51 | 48 | 49 | 48 | 51 | 56 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 319.3 | 280.0 | 260.4 | 234.0 | 210.8 | 186.0 | 204.6 | 238.7 | 240.0 | 291.4 | 300.0 | 316.2 | 3,081.4 |

| Source: NOAA[78] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Cristo Redentor | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.0 (50) |

9.8 (49.6) |

7.2 (45) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

0.7 (33.3) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

2.7 (36.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.3 (31.5) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−10.4 (13.3) |

−8.9 (16) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−3.9 (25) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 57.0 | 54.5 | 54.0 | 56.5 | 57.5 | 59.0 | 55.5 | 57.0 | 58.0 | 64.5 | 59.0 | 56.0 | 57.4 |

| Source: Secretaria de Mineria[79] | |||||||||||||

Pampas

The Pampas includes all of Buenos Aires Province, eastern and southern Córdoba Province, eastern La Pampa Province, and southern Santa Fe Province.[80] It is subdivided into two parts: the humid Pampas to the east, and the dry/semi–arid Pampas to the west.[7]

This region's land is appropriate for agricultural and livestock activities. It is mostly a flat area, interrupted only by the Tandilia and Ventana hills in its southern portion.[81] The climate of the Pampas is temperate and humid with no dry season, featuring hot summers and mild winters (Cfa/Cfb according to the Köppen climate classification).[81][82][83] The weather in the Pampas is variable due to the contrasting air masses and frontal storms that impact the region.[84] Maritime polar air from the south produces the cool pampero winds, while warm humid tropical air from the north produces sultry nortes - a gentle wind usually from the northeast formed by trade winds, and the South Atlantic High that brings cloudy, hot, and humid weather and is responsible for bringing heat waves.[84][85] The Pampas are influenced by the El Niño–Southern Oscillation which is responsible for variations in annual precipitation.[86][87] An El Niño year often leads to higher precipitation, while a La Niña year leads to lower precipitation.[87] The Pampas are moderately sunny, ranging from an average of 4–5 hours of sunshine per day during the winter months to 8–9 hours in summer.[51]

Precipitation

Precipitation decreases from east to west,[88] and ranges from 1,200 mm (47 in) in the northeast, to under 500 mm (20 in) in the south and west.[87] Most regions receive 700 to 800 mm (28 to 31 in) of precipitation per year.[87] Precipitation is fairly evenly distributed throughout the year in the easternmost parts, while in the western parts most of the precipitation is concentrated during the summer months and winters are drier.[81][89] In many places precipitation, which mostly occurs in the form of convective thunderstorms, is high during summer.[10][90] These thunderstorms form when cold air from the south, caused by the pampero wind, meets humid tropical air masses from the north,[84] and are some of the most intense storms in the world, with the most frequent lightning and the highest convective cloud tops.[91][92] These severe thunderstorms produce intense amounts of precipitation [87] and hailstorms, and can cause both floods and flash floods. As well, the Pampas is the most consistently active tornado region outside the central and southeastern United States.[93] Autumn and spring bring periods of very rainy weather followed by dry, mild stretches.[87] Places in the east receive rainfall throughout autumn, whereas in the west it quickly becomes very dry.[87] Winters are drier in most places due to weaker easterly winds, and stronger southerly winds, which prevent moist air from coming in.[89] In winter, most of the precipitation occurs from frontal systems associated with cyclogenesis and strong southeasterly winds (sudestada), which bring long periods of precipitation, and cloudiness, particularly in the southern and eastern parts.[19][94][17] As such, precipitation is more evenly distributed in the eastern parts than the western parts, which are further away from these frontal systems.[94] Dull, grey, and damp weather characterize winters in the Pampas.[19] Snowfall is extremely rare; when it does snow, it usually lasts for only a day or two.[19]

Temperatures

Annual temperatures range from 17 °C (63 °F) in the northern parts to 14 °C (57 °F) in the south.[82] Summers in the Pampas are hot and humid; coastal areas are moderated by the cold Malvinas Current.[84] Heat waves that can bring temperatures in the 36 to 40 °C (97 to 104 °F) range for a few days.[87] These are usually followed by a day or two of strong pampero winds from the south, which bring cool, dry air.[87] Autumn arrives in March and brings periods of mild daytime temperatures and cool nights.[87] Generally, frost arrives in early April in the southernmost areas, and in late May in the north and ends by mid-September - although the dates of the first and last frosts can vary from year to year.[81][82][87] Frost is rarely intense, nor prolonged, and does not occur in some years.[51][19] Winters are mild with frequent frosts and cold spells.[84] Temperatures are usually mild during the day and cold during the night.[83] Occasionally, tropical air masses from the north may move southward, providing relief from the cool, damp temperatures.[19] On the other hand, the sudestada and the pampero winds bring periods of cool to cold temperatures.[17][84]

Statistics for selected locations

| Climate data for Pilar, Córdoba Province (Pampean climate with dry season in winter) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.3 (86.5) |

29.3 (84.7) |

26.9 (80.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

17.4 (63.3) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.8 (67.6) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.1 (77.2) |

27.6 (81.7) |

29.5 (85.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

15.0 (59) |

11.7 (53.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

5.0 (41) |

4.7 (40.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

7.8 (46) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.6 (61.9) |

11.3 (52.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 137.7 (5.421) |

104.2 (4.102) |

100.2 (3.945) |

52.3 (2.059) |

17.9 (0.705) |

13.0 (0.512) |

15.9 (0.626) |

9.2 (0.362) |

39.7 (1.563) |

63.4 (2.496) |

94.3 (3.713) |

143.5 (5.65) |

791.3 (31.154) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68 | 71 | 76 | 75 | 72 | 71 | 69 | 61 | 58 | 62 | 63 | 65 | 68 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 275.9 | 240.8 | 226.3 | 201.0 | 189.1 | 168.0 | 182.9 | 213.9 | 222.0 | 248.0 | 267.0 | 269.7 | 2,704.6 |

| Source: NOAA[95] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Rosario | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.8 (87.4) |

29.5 (85.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

26.6 (79.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

23.5 (74.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

17.0 (62.6) |

15.2 (59.4) |

11.7 (53.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.3 (41.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

5.7 (42.3) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

11.2 (52.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 104.5 (4.114) |

116.4 (4.583) |

164.6 (6.48) |

79.7 (3.138) |

46.7 (1.839) |

36.6 (1.441) |

36.8 (1.449) |

36.7 (1.445) |

61.6 (2.425) |

91.8 (3.614) |

98.3 (3.87) |

120.0 (4.724) |

993.7 (39.122) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69 | 72 | 78 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 77 | 74 | 73 | 70 | 68 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 294.5 | 248.6 | 232.5 | 204.0 | 179.8 | 150.0 | 161.2 | 189.1 | 207.0 | 238.7 | 270.0 | 282.1 | 2,657.5 |

| Source #1: NOAA[96] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun, 1961–1990)[97] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Mar del Plata (Pampean climate with Oceanic influences) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 25.5 (77.9) |

25.2 (77.4) |

22.6 (72.7) |

20.2 (68.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.1 (55.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.5 (63.5) |

21.0 (69.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

19.1 (66.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 14.5 (58.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

4.7 (40.5) |

5.0 (41) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 100 (3.94) |

84 (3.31) |

98 (3.86) |

58 (2.28) |

64 (2.52) |

64 (2.52) |

63 (2.48) |

93 (3.66) |

57 (2.24) |

68 (2.68) |

56 (2.2) |

87 (3.43) |

892 (35.12) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 84 | 83 | 82 | 82 | 81 | 80 | 75 | 80 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 288.3 | 234.5 | 232.5 | 195.0 | 167.4 | 120.0 | 127.1 | 164.3 | 174.0 | 210.8 | 222.0 | 269.7 | 2,405.6 |

| Source: UNLP[63][98] | |||||||||||||

Patagonia

Chubut, Neuquén, Río Negro, Santa Cruz, and Tierra del Fuego are the provinces that make up Patagonia.[7][36]

The Patagonian climate is classified as arid to semi-arid and temperate to cool temperate.[102][103] The exception is the Bosque Andino Patagónico, a forested area located in the extreme west and southern parts of Tierra del Fuego Province, which has a humid, wet, and cool to cold climate.[104]:71–72 One defining characteristic is the strong winds from the west which blow year round (stronger in summer than in winter). These favor evaporation, and are a factor in making the region mostly arid.[105] Mean annual wind speeds range between 15 to 22 km/h (9 to 14 mph), although gusts of over 100 km/h (62 mph) are common.[100] There are three major factors that influence the climate of this region: the Andes, the South Pacific and the South Atlantic Highs, and higher insolation in eastern than in western areas.[106]

The Andes play a crucial role in determining the climate of Patagonia because their north–south orientation creates a barrier for humid air masses coming from the Pacific Ocean.[103][107] Since the predominant wind is from the west and most air masses come from the Pacific Ocean, the Andes cause these air masses to ascend, cooling adiabatically.[103][105] Most of the moisture is dropped on the Chilean side, resulting in abundant precipitation, while in much of the Argentine side, the air warms adiabatically and becomes drier as it descends.[103][105] As a result, the Andes create an extensive rain-shadow in much of Argentine Patagonia, causing most of the region to be arid.[107][105] South of 52oS, the Andes are lower in elevation, reducing the rain shadow effect in Tierra del Fuego Province, allowing forests to thrive on the Atlantic coast.[101]

Patagonia is located between the subtropical high pressure belt, and the subpolar low pressure zone, meaning it is exposed to westerly winds that are strong, since south of 40o S, there is little land to block these winds.[100][101] Being located between the semipermanent South Pacific and the South Atlantic Highs at around 30oS, and the Subpolar Low at arount 60o S, the movement of the high and low pressure systems, along with ocean currents, determine the precipitation pattern.[103] During winter, both the South Pacific and South Atlantic highs move to the north, while the Subpolar Low strengthens, which, when combined with higher ocean temperatures than the surrounding land, results in higher precipitation during this time of the year.[103][105] Due to the northward migration of the South Pacific High, more frontal systems can pass through, allowing for more precipitation to occur.[105] During summer, the South Pacific High migrates southward, preventing the passage of fronts, and cyclones that can cause precipitation to occur, resulting in lower precipitation during this time of the year.[105] Northeastern areas, along with southern parts of the region, are influenced by air masses from the Atlantic Ocean, resulting in precipitation being more evenly distributed throughout the year.[103] Most precipitation comes from frontal systems,[103] particularly stationary fronts that bring humid air from the Atlantic Ocean.[105]

Cold fronts usually move from west to east, or from southwest to northeast, but rarely from the south.[105] Because of this, these cold fronts do not result in the cold being intense since they are moderated as they pass over the surrounding oceans.[105] In the rare cases when cold fronts move northwards from the south (Antarctica), the cold air masses are not moderated by the surrounding oceans, resulting in very cold temperatures throughout the region.[105] In general, the passage of cold fronts is more common in the south than in the north, and occurs more in winter than in summer.[105] The movement of warm, subtropical air into the region occurs frequently in summer up to 46oS.[105] When warm subtropical air arrives in the region, the air is dry, resulting in little precipitation, and causes temperatures to be higher than the those observed in northeast Argentina.[105]

Precipitation

The influence of the Pacific Ocean, general circulation patterns, and the topographic barrier caused by the Andes, results in one of the strongest precipitation gradients in the world.[103][108] Precipitation decreases steeply from west to east, ranging from 4,000 mm (160 in) in the west on the Andean foothills at 41oS, to 150 mm (6 in) in the central plateaus.[107][108] For example, while mean annual precipitation is more 1,000 mm (39 in) at the Andean foothills, in less than 100 km (62 mi) to the east, precipitation decreases to 200 mm (8 in).[105] The high precipitation in the Andes in this region supports glaciers and permanent snowfields.[51]

Most of the region receives less than 200 mm (8 in) of precipitation per year, although some areas can receive less than 100 mm (4 in).[105] In northern Río Negro Province and eastern Neuquén Province, mean annual precipitation is around 300 mm (12 in) while south of 50oS, precipitation increases southwards, reaching up to 600 to 800 mm (24 to 31 in).[105] There is a narrow transition zone running down from 39oS to 47oS that receives about 400 mm (16 in) of precipitation a year.[109] Much of northwestern Patagonia in the Andes, corresponding to the northern parts of the Bosque Andino Patagónico region, receives abundant precipitation in winter with occasional droughts in summer, allowing it to support forests with dense coverage.[104]:72[99] With the exception of certain areas such as Puerto Blest, no major towns receive more than 1,000 mm (39 in) of precipitation a year.[109] The southern parts of the Bosque Andino Patagónico region receive only 200 to 500 mm (8 to 20 in) resulting in less dense forest coverage.[104]:72[99] The lower precipitation, compared to the northern parts, is due to the winds being more intense and drier, favouring evapotranspiration.[104]:72

The aridity of the region is due to the combination of low precipitation, strong winds, and high temperatures in the summer months, each of which cause high evaporation rates.[3] Mean evapotranspiration ranges from 550 to 750 mm (22 to 30 in), which decreases from northeast to southwest.[3] In most of Patagonia, precipitation is concentrated in the winter months with the exception of northeastern and southern areas of the region which have a more even distribution of precipitation throughout the year.[103][110][105] As a result, except for these areas, the winter maxima in precipitation results in a strong water deficit in the summer.[103] Most precipitation events are light; each event usually results in less than 5 mm (0.2 in).[103] Thunderstorms are infrequent in the region, occurring an average of 5 days per year, only during summer.[105] In Tierra del Fuego, thunderstorms are non-existent.[105] Snowfall occurs on 5 to 20 days per year, mainly in the west and south.[3] These snowfall events can result in strong snow storms.[4]

Despite the low precipitation, Patagonia is cloudy, with the mean cloud cover ranging from 50% in eastern parts of Neuquén Province and northeast Río Negro Province to 70% in Tierra del Fuego Province;[105] the region has one of the highest percentages of cloud cover in Argentina.[103] In general, mountainous areas are the cloudiest, and coastal areas are cloudier than inland areas.[105] Northern areas are sunnier (50% possible sunshine)[note 4] than the southern parts of the region such as western Santa Cruz and Tierra del Fuego Provinces (less than 40% possible sunshine).[103] The southernmost islands receive some of the lowest average annual sunshine hours in the world.[111]

Temperatures

Temperatures are relatively cold for its latitude due to the cold Malvinas Current and the high altitude.[105] For example, in Tierra del Fuego temperatures are colder than at equal latitudes in the northern hemisphere in Europe since they are influenced by the cold Malvinas Current rather than the warm North Atlantic Current.[112]:17 A characteristic of the temperature pattern is the NW–SE distribution of isotherms due to the presence of the Andes.[103]

The warmest areas are in northern parts of Río Negro and Neuquén Provinces where mean annual temperatures range from 13 to 15 °C (55 to 59 °F), while the coldest are in western Santa Cruz and Tierra del Fuego Provinces where mean annual temperatures range from 5 to 8 °C (41 to 46 °F).[105] On the Patagonian plateaus, mean annual temperatures range from 8 to 10 °C (46 to 50 °F) which decreases towards the west.[108] The daily and annual range of temperatures on these plateaus is very high.[109][113] The Atlantic Ocean moderates the climate of coastal areas resulting in a lower annual and daily range of temperatures.[109][114] Towards the south, where land masses are narrow, the Pacific Ocean influences coastal areas in addition to the Atlantic Ocean, ensuring that the cold is neither prolonged nor intense.[51][109] At higher altitudes in the Andes, stretching from Neuquén Province to Tierra del Fuego Province, mean annual temperatures are below 5 °C (41 °F).[105] Generally, mean annual temperatures vary more with altitude than with latitude since the temperature gradient for latitude is relatively moderate owing to ocean currents.[105] Summers have a less uniform distribution of temperature, and in the months December to January mean temperatures range from 24 °C (75 °F) in northern Río Negro Province and eastern parts of Neuquén Province to 9 °C (48 °F) in Tierra del Fuego.[105] Winters have a more uniform temperature distribution.[105] In July, mean temperatures are above 0 °C (32 °F) in all of extra–Andean Patagonia,[103] ranging from 7 °C (45 °F) in the north to around 0 °C (32 °F) in Ushuaia.[105]

Being exposed to strong westerly winds can decrease the perception of temperature (wind chill), particularly in summer.[103] The wind lowers the perception of the mean annual temperature by 4.2 °C (7.6 °F) throughout the region.[103] The annual range of temperatures in Patagonia is lower than in areas in the Northern Hemisphere at the same latitude owing to the maritime influences of the sea.[103][111] In Patagonia, the annual range of temperatures ranges from 16 °C (29 °F) in the north[103][111] and decreases progressively southwards to 4 °C (7 °F) on the southernmost islands.[111] This contrasts with an annual range of more than 20 °C (36 °F) in North America at latitudes above 50oN.[103] Absolute maximum temperatures can exceed 40 °C (104 °F) in the northern Río Negro Province and Neuquén Province, while in much of the region, they can exceed 30 °C (86 °F).[105] Further south in Tierra del Fuego Province, absolute maximum temperatures do not exceed 30 °C (86 °F), while in the southernmost islands, they do not exceed 20 °C (68 °F).[111] Absolute minimum temperatures are more than −15 °C (5 °F) in coastal areas, while in the central Patagonian plateaus, they can reach below −20 °C (−4 °F).[105]

Statistics for selected locations

| Climate data for Lago Frias (wettest place in Argentina)[115] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 159.20 (6.2677) |

149.34 (5.8795) |

214.67 (8.4516) |

277.06 (10.9079) |

502.29 (19.7752) |

502.00 (19.7638) |

447.44 (17.6157) |

346.32 (13.6346) |

277.98 (10.9441) |

187.37 (7.3768) |

234.69 (9.2398) |

181.69 (7.1531) |

3,480.06 (137.0102) |

| Source: Secretaria de Mineria[116] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for San Carlos de Bariloche Airport (zone of transition) 1961–1990 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 21.5 (70.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

6.7 (44.1) |

6.4 (43.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.0 (57.2) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.7 (67.5) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 6.4 (43.5) |

5.7 (42.3) |

4.0 (39.2) |

1.8 (35.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

1.1 (34) |

3.5 (38.3) |

5.4 (41.7) |

2.1 (35.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 22.2 (0.874) |

21.7 (0.854) |

29.2 (1.15) |

53.5 (2.106) |

134.0 (5.276) |

140.7 (5.539) |

128.7 (5.067) |

115.6 (4.551) |

57.8 (2.276) |

38.8 (1.528) |

24.8 (0.976) |

32.0 (1.26) |

799.0 (31.457) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 60 | 62 | 67 | 74 | 81 | 84 | 84 | 81 | 75 | 68 | 63 | 61 | 72 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 347.2 | 277.2 | 251.1 | 186.0 | 136.4 | 111.0 | 117.8 | 155.0 | 192.0 | 251.1 | 309.0 | 334.8 | 2,668.6 |

| Source: NOAA[117] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Punta Delgada Lighthouse, Valdes Peninsula (Patagonian coast) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 22.8 (73) |

23.2 (73.8) |

21.1 (70) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

12.2 (54) |

11.2 (52.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

17.2 (63) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.3 (63.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 13.1 (55.6) |

13.3 (55.9) |

12.0 (53.6) |

10.2 (50.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.3 (39.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

7.4 (45.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 13.9 (0.547) |

10.5 (0.413) |

23.5 (0.925) |

25.9 (1.02) |

25.0 (0.984) |

25.2 (0.992) |

27.9 (1.098) |

14.8 (0.583) |

16.5 (0.65) |

12.1 (0.476) |

13.1 (0.516) |

15.1 (0.594) |

223.5 (8.799) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68.0 | 68.5 | 68.5 | 68.5 | 72.5 | 76.5 | 77.0 | 72.5 | 72.5 | 68.0 | 69.0 | 67.5 | 70.8 |

| Source: Secretaria de Mineria[118] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Paso de Indios (Patagonian plateau) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 26.4 (79.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

22.6 (72.7) |

17.6 (63.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

8.9 (48) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.1 (52) |

15.1 (59.2) |

18.7 (65.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

25.0 (77) |

17.9 (64.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10.1 (50.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.0 (39.2) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

1.1 (34) |

3.8 (38.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 7.6 (0.299) |

12.7 (0.5) |

11.5 (0.453) |

16.4 (0.646) |

26.0 (1.024) |

22.9 (0.902) |

23.9 (0.941) |

18.0 (0.709) |

17.4 (0.685) |

13.7 (0.539) |

8.0 (0.315) |

9.2 (0.362) |

187.3 (7.374) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 40.0 | 43.0 | 47.5 | 53.0 | 64.5 | 69.5 | 68.5 | 61.5 | 54.5 | 47.5 | 44.0 | 41.5 | 52.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 282.1 | 257.1 | 223.2 | 159.0 | 133.3 | 108.0 | 120.9 | 148.8 | 171.0 | 229.4 | 249.0 | 263.5 | 2,345.3 |

| Source: Secretaria de Mineria[119] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Ushuaia Airport (Tierra del Fuego) 1961–1990 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.9 (57) |

13.7 (56.7) |

12.2 (54) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

5.3 (41.5) |

3.9 (39) |

2.3 (36.1) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−1 (30) |

0.5 (32.9) |

2.3 (36.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

2.0 (35.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39.0 (1.535) |

45.2 (1.78) |

52.3 (2.059) |

56.1 (2.209) |

53.4 (2.102) |

48.3 (1.902) |

36.4 (1.433) |

45.2 (1.78) |

41.7 (1.642) |

35.0 (1.378) |

34.6 (1.362) |

42.5 (1.673) |

529.7 (20.854) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 76 | 78 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 82 | 80 | 76 | 73 | 72 | 74 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 167.4 | 146.9 | 133.3 | 102.0 | 68.2 | 42.0 | 55.8 | 83.7 | 123.0 | 164.3 | 180.0 | 167.4 | 1,434 |

| Source #1: NOAA[120] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Secretaria de Mineria (sun, 1901–1990)[121] | |||||||||||||

See also

- Climate of Argentina

- Climate of Buenos Aires

- Climate of the Falkland Islands

- Natural regions of Chile

- Regions of Argentina

Notes

- ↑ Argentina claims sovereignty over part of Antarctica and the Falkland Islands. However, territorial claims in Antarctica are suspended by the Antarctic Treaty while the United Kingdom exercises de facto control of the Falkland Islands

- ↑ According to the Minister of the Interior, the north consists of the following provinces: Catamarca, Chaco, Corrientes, Formosa, Jujuy, La Rioja, Misiones, Salta, Santiago del Estero, and Tucumán.[1]

- 1 2 According to INTA, the temperate valleys include the Lerma Valley, Siancas Valley in Salta Province and the Pericos Valley and the temperate valleys of Jujuy, which includes the two provincial capitals

- ↑ Percent possible sunshine is defined as the percentage of theoretical sunshine a place receives where theoretical sunshine is defined as the highest amount of sunshine that a place possibly receives if there is no obstruction of sunlight from coming in.

References

- ↑ "Región Norte Grande" (in Spanish). Ministerio del Interior, Obras Públicas y Vivienda. Archived from the original on 22 June 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- 1 2 "Regiones Geográficas" (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Educación Tecnológica. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Fernandez, Osvaldo; Busso, Carlos. "Arid and semi–arid rangelands: two thirds of Argentina" (PDF). The Agricultural University of Iceland. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Geography and Climate of Argentina". Government of Argentina. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ↑ Barros, Vicente; Boninsegna, José; Camilloni, Inés; Chidiak, Martina; Magrín, Graciela; Rusticucci, Matilde (2014). "Climate change in Argentina: trends, projections, impacts and adaptation". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. John Wiley & Sons. 6 (2): 151–169. doi:10.1002/wcc.316. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 USDA 1968, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 "Argentina in Brief" (in Spanish). Embassy of Argentina in Australia. Archived from the original on 20 March 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ↑ Moore 1948, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "Sintesis Abarcativas–Comparativas Fisico Ambientales y Macroscoioeconomicas" (in Spanish). Secretaria de Mineria de la Nacion (Argentina). Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Climate Overview" (PDF). Met Office. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ↑ Penalba, Olga; Llano, Maria (2006). Temporal Variability in the Length of No–Rain Spells in Argentina (PDF). 8th International Conference on Southern Hemisphere Meteorology and Oceanography Society; 2006. Foz de Iguazu. pp. 333–341. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Vulnerabilidad de los Recursos Hídricos en el Litoral–Mesopotamia–Tomo I" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad Naciónal del Litoral. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Moore 1948, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Región del Noreste" (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministerio del Interior y Transporte. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Provincia de Corrientes–Clima Y Metéorologia" (in Spanish). Secretaria de Mineria de la Nacion (Argentina). Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Provincia de Entre Rios–Clima Y Metéorologia" (in Spanish). Secretaria de Mineria de la Nacion (Argentina). Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Sudestada" (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Provincia de Misiones–Clima Y Metéorologia" (in Spanish). Secretaria de Mineria de la Nacion (Argentina). Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fittkau 1969, p. 73.

- ↑ "Posadas Aero Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ↑ "Klimatafel von Posadas, Prov. Misiones / Argentinien" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ "Parana Aero Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Atlas del Gran Chaco Americano" (PDF) (in Spanish). Government of Argentina. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- 1 2 "Santiago del Estero: Descripción". Atlas Climático Región Noroeste (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ↑ "Región Chaqueña" (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gorleri, Máximo (2005). "Caracterización Climática del Chaco Húmedo" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Clima de la Región Chaqueña Subhúmeda" (PDF) (in Spanish). Secretaría de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Compagnucci, Rosa; Eduardo, Agosta; Vargas, W. (2002). "Climatic change and quasi-oscillations in central-west Argentina summer precipitation: main features and coherent behaviour with southern African region" (PDF). Climate Dynamics. Springer. 18 (5): 421–435. Bibcode:2002ClDy...18..421C. doi:10.1007/s003820100183. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Seluchi, Marcelo; Marengo, José (2000). "Tropical–Midlatitude Exchange of Air Masses During Summer and Winter in South America: Climatic Aspects and Examples of Intense Events". International Journal of Climatology. John Wiley & Sons. 20 (10): 1167–1190. doi:10.1002/1097-0088(200008)20:10<1167::AID-JOC526>3.0.CO;2-T. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- 1 2 "ECOLOGÍA Y USO DEL FUEGO EN LA REGIÓN CHAQUEÑA ARGENTINA: UNA REVISIÓN" (PDF) (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Gran Chaco". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "Capitulo 4: Diagnostico Ambiental del Área de Influencia" (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ↑ "Rivadavia Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Klimatafel von Rividavia, Prov. Salta / Argentinien" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ "Formosa AERO Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Valores Estadisticos del trimester (Diciembre–Febrero)". Boletín de Tendencias Climáticas–Diciembre 2011 (in Spanish). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- 1 2 "Región del Noroeste" (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministerio del Interior y Transporte. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Ahumada, Ana (2002). "Periglacial phenomena in the high mountains of northwestern Argentina" (PDF). South African Journal of Science. 98: 166–170. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Bobba, María (2011). "Causas de Las Sequías de la Región del NOA (Argentina)". Revista Geográfica de América Central. Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica. 47. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Bianchi, A.; Yáñez, C.; Acuña, L. "Base de Datos Mensuales de Precipitaciones del Noroeste Argentino" (PDF) (in Spanish). Oficina de Riesgo Agropecuario. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Trauth, Martin; Alonso, Ricardo; Haselton, Kirk; Hermanns, Reginald; Strecker, Manfred (2000). "Climate change and mass movements in the NW Argentine Andes". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. Elsevier. 179 (2): 243–256. Bibcode:2000E&PSL.179..243T. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(00)00127-8. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Oncken 2006, p. 268.

- 1 2 3 4 "Selva Tucumano Boliviana" (PDF). Atlas de los Bosques Nativos Argentinos (in Spanish). Secretaría de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- 1 2 Bravo, Gonzalo; Bianchi, Alberto; Volante, José; Salas, Susana; Sempronii, Guillermo; Vicini, Luis; Fernandez, Miguel. "Regiones Agroeconómicas del Noroeste Argentino" (PDF) (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 Carrillo Castellanos 1998, p. 129.

- 1 2 Buitrago, Luis. "El Clima de la Provincia de Jujuy" (PDF) (in Spanish). Dirección Provincial de Estadística y Censos–Provincia de Jujuy. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Goméz del Campo, Maria; Morales–Sillero, A.; Vita Serman, F.; Rousseaux, M.; Searles, P. "Olive Growing in the arid valleys of Northwest Argentina (provinces of Catamarca, La Rioja and San Juan)" (PDF). International Olive Council. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ Oncken 2006, p. 267.

- 1 2 3 "The Vegetation of Northwestern Argentina (NOA)". Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Paoli, Héctor; Volante, José; Ganam, Enrique; Bianchi, Alberto; Fernandez, Daniel; Noé, Yanina. "Aprovechamiento de Los Recursos Hídricos y Tecnologia de Riego en el Altiplano Argentino" (PDF) (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Argentina". BBC Weather. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Strecker, M.; Alonso, R.; Bookhagen, B.; Carrapa, B.; Hilley, G.; Sobel, E.; Trauth, M. (2007). "Tectonics and Climate of the Southern Central Andes" (PDF). Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. Annual Reviews. 35: 747–787. Bibcode:2007AREPS..35..747S. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.35.031306.140158. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ Altobelli, Fabiana. "Diagnostico del Manejo del Agua en Cuencas Tabacaleras del Valle de Lerma, Salta, Argentina" (PDF) (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- 1 2 Canziani, Pablo; Scarel, Eduardo. "South American Viticulture, Wine Production, and Climate Change" (PDF). Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Reseña de la vitivinicultura argentina" (in Spanish). Acenología. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- 1 2 Karlin, Marcos (2012). "Cambios temporales del clima en la subregión del Chaco Árido" (PDF). Multequina–Latin American Journal of Natural Resources. Dirección de Recursos Naturales Renovables de Mendoza; Instituto Argentino de Investigaciones de las Zonas Aridas (IADIZA-CONICET). 21: 3–16. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "Provincia de Salta—Clima y Meteorologia" (in Spanish). Secretaria de Mineria de la Nacion (Argentina). Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ↑ "Datos Meteorológicos Registrados en las Distintas Estación de la Provincia de Jujuy" (in Spanish). Secretaria de Mineria de la Nacion (Argentina). Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ "Estación Meteorológica (EM) Cerrillos-INTA" (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ↑ "La Rioja Aero Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 15 March 2015.