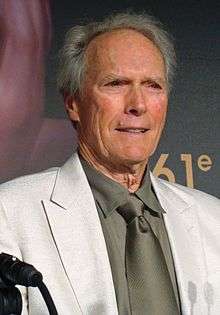

Clint Eastwood in the 1980s

a series on Clint Eastwood |

|---|

The career of Clint Eastwood in the 1980s included several films, television direction, and a stint in politics.

Films and television

In 1980, Eastwood directed and played the main attraction in a traveling Wild West Show in the comedy film, Bronco Billy. His children Kyle and Alison had small roles as orphans.[1] Eastwood starred alongside Locke, Scatman Crothers, Sam Bottoms, Dan Vadis, Sierra Pecheur and Geoff Lewis.[2] Filming commenced on October 1, 1979 in the Boise, Idaho area and was shot in five and a half weeks on a low budget of $5 million, two-four weeks before schedule.[3][4] Eastwood has cited Bronco Billy as being one of the most affable shoots of his entire career, and biographer Richard Schickel has argued that the character of Bronco Billy is his most self-referential work.[5][6] The film was a commercial failure,[7] was but appreciated by critics with Kenneth Turan of New West saying, "it shows enough class to rank as the unexpected joy of the season".[8] Janet Maslin of The New York Times believed the film was "the best and funniest Clint Eastwood movie in quite a while", praising Eastwood's directing and the way he intricately juxtaposes the old West and the new.[9] Later in 1980, he reprised his role in the sequel to Every Which Way But Loose entitled Any Which Way You Can. The film received a number of bad reviews from critics, although Janet Maslin of the New York Times described it as, "funnier and even better than its predecessor".[7] The film, however, became another box-office success and was among the top five highest-grossing films of the year.

In 1982, Eastwood directed and starred in Honkytonk Man, based on the novel by Clancy Carlile about an aspiring country music singer named Red Stovall, set during the Great Depression. The script was adapted slightly from the novel; the scene in the novel of where Red gives a reefer to his fourteen-year-old son (played by real-life son Kyle) was not approved by Eastwood and altered and the ending was also changed to the playing on the radio of a song written by Red on his death bed, shortly before his burial.[10] The film was shot in the summer of 1982 within six weeks.[11] The first part of the movie was filmed in Bird's Landing, California, although the majority of this feature was filmed in and around Calaveras County, east of Stockton, California. Exterior scenes include Main Street, Mountain Ranch; Main Street, Sheepranch; and the Pioneer Hotel in Sheepranch. Extras were locally hired and many of the towns' residents are seen in the movie. The film received a mixed reception upon release, although it has a high score of 93% on Rotten Tomatoes. In 1982, Eastwood also directed, produced and starred in the Cold War-themed Firefox, based on a 1977 novel with the same name by British novelist Craig Thomas. Firefox is an espionage thriller, about a retired Air Force Special Forces Expert, recruited to steal a Soviet supersonic war plane from Moscow. Russian filming locations were not possible due to the Cold War, and much footage was shot at the Thule Air Base in Greenland and in Austria to simulate many of the Eurasian story locations.[12] The film was actually shot before Honkeytonk Man but was released after it.

The fourth Dirty Harry film Sudden Impact (1983), is widely considered to be the darkest, "dirtiest" and most violent film of the series. This would be the last time he starred in a film with frequent leading lady Sondra Locke. The script, written by Joseph Stinson, is about a woman (Locke) who avenges the rape of herself and her sister (now a vegetable) by a ruthless gang at a fairground. The woman systematically murders her rapists one by one, shooting them once in the genitals and once in the head. Pat Hingle and Bradford Dillman also starred alongside Eastwood and footage was shot in the spring and early summer of 1983. The line, "Go ahead, make my day", uttered by Eastwood during an earlier scene in which his regular morning cafe is threatened by robbers, is often cited as one of cinema's immortal lines and was famously referenced by President Ronald Reagan in his campaigns. The film was the highest earning of all the Dirty Harry films, earning $70 million and received rave reviews, with many critics praising the feminist aspects of the film through its explorations of the physical and psychological consequences of rape.[13]

In 1984, Eastwood starred in the provocative thriller Tightrope, inspired by newspaper articles about an elusive Bay Area rapist. Set in New Orleans (to avoid confusion with the Dirty Harry films),[14] Eastwood starred as a single-father cop in a mid-life crisis, lured by the promise of kinky sex. The film explored the way his character is drawn into the killer's tortured psychology and fascination for sadomasochism.[15] Complicating matters are his struggle to single-handedly raise two young daughters (one of which was his real daughter Alison), a growing relationship with a tough rape prevention officer played by Geneviève Bujold, and the troubling thought that the killer shares his own sexual preferences (bondage, masochism, etc.).[16] During filming, Eastwood had an affair with the first murder victim in the film, Jamie Rose.[17] Pierre Rissient arranged for the film to premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, but failed to win any awards. It opened in 1535 theatres in the summer of 1984 and earned record takings in the first ten days, eventually earnings revenues of $70 million domestically.[18] The film was also a critical success, with J. Hoberman in the Village Voice describing Clint as " one of the most masterful under-actors in American movies" and David Denby commenting that he has become a "very troubled movie icon".[19][20] Others such as Jack Kroll of Newsweek noted the sexuality of the film and vulnerability of Eastwood's character, remarking, "He gets better as he gets older; he seems to be creating new nuances".[21]

Eastwood next starred in the period comedy City Heat (1984) with Burt Reynolds. The film was initially running under the title, Kansas City Jazz under the directorship of Blake Edwards. The film is about a private eye and his partner mixed up with gangsters in the prohibition era in the 1930s. During filming, Eastwood conflicted with Edwards and producer Tony Adams, stipulating "creative differences" as the reason, leading to Edward's replacement with Richard Benjamin.[18] Principal photography began in May 1984 and the film was released in North America in December 1984, grossing around $50 million domestically.

In 1985, Eastwood made his only foray into TV direction to date with the Amazing Stories episode Vanessa In The Garden, starring Harvey Keitel and Sondra Locke; this was his first collaboration with writer/executive producer Steven Spielberg (Spielberg later produced Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima[22]). Eastwood revisited the western genre, directing and starring in Pale Rider. The film is based on the classic Western Shane (1953); a preachers descends magically from the mists of the Sierras and takes the side of the placer miners amidst the California Gold Rush of 1850.[23] The ending is also similar, but the story is told from the girl's viewpoint (Megan) and explores the psychosexual and psychospiritual bridge between childhood and womanhood as both mother and daughter compete for the preacher's affections. The film also bears similarities to Eastwood's previous Man with No Name character, and his 1973 western High Plains Drifter in its themes of morality and justice and exploration of the supernatural. The title is a reference to the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, as the rider of a pale horse is Death, cited in Revelation Chapter 6, Verse 8.[24] It was primarily filmed in the Boulder Mountains and the SNRA in central Idaho, just north of Sun Valley in late 1984. The opening credits scene featured the jagged Sawtooth Mountains south of Stanley. Train-station scenes were filmed in Tuolumne County, California, near Jamestown. Scenes of a more established Gold Rush town (in which Eastwood's character picks up his pistol at a Wells Fargo office) were filmed in the real Gold Rush town of Columbia, also in Tuolumne County, California. The film also featured Michael Moriarty, Carrie Snodgress, Christopher Penn, Richard Dysart, Sydney Penny, Richard Kiel, Doug McGrath and John Russell. The film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, but was not a success there, given that international critics believed the film to be too overtly commercial for the festival.[25] Nevertheless, Pale Rider became one of Eastwood's most successful films to date in the eyes of critics, earning him the wide critical acclaim he had sought for so long. Jeffrey Lyons of Sneak Previews said, "Easily one of the best films of the year, and one of the best westerns in a long, long time". Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune said, "This year (1985) will go down in film history as the moment Clint Eastwood finally earned respect as an artist".[26]

In 1986, Eastwood starred in the military drama Heartbreak Ridge, about the 1983 U.S. invasion of Grenada, West Indies, with a portion of the movie filmed on the island itself. It co-starred Marsha Mason. However, the title comes from the Battle of Heartbreak Ridge in the Korean War, based around Eastwood's character of Tom Highway, an ageing United States Marine Gunnery Sergeant and Korean War veteran, who was awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions there. Eastwood incorporated more scenes of action and comedy into the film than was initially intended by the original drafter, James Carabatsos, and worked hard with Megan Rose to revise it.[27] Eastwood and producer Fritz Manes meanwhile, intent on making the film realistic, visited the Pentagon and various air bases to request assistance and approval.[28] The U.S. army refused to help, due to Highway being portrayed as a hard drinker, divorced from his wife, and using unapproved motivational methods to his troops, an image the army did not want. They informed the production team that the characterisation lacked credibility and that Eastwood's character was an outdated stereotype and that he was too old for the role.[29] They instead approached the United States Marine Corps, and Lieutenant Colonel Fred Peck was hired as a spokesman for the military during filming and to guide Eastwood's team to making the characters and scenes more realistic. The production and filming of Heartbreak Ridge was marred by internal disagreements, between Eastwood and long term friend Fritz Manes who was producing it and between Eastwood and the DOD who expressed contempt at the film.[29][30] During the film, Peck came to head with Eastwood over a scene involving Eastwood offering a drink in a flask to the Sergeant Major; Peck stood his ground and insisted this scene was laughable. Eastwood eventually relented but the relationship between the producers continued to sour.[31] Within months, Manes was fired and Eastwood had rid of his best friend and producing partner, replacing him with David Valdes.[32] The film released in 1470 theatres, grossing a very respectable $70 million domestically.[33]

Eastwood's fifth and final Dirty Harry film, The Dead Pool was released in 1988. It co-starred Liam Neeson, Patricia Clarkson, and a young Jim Carrey. The Dead Pool, grossed $37,903,295, relatively low takings for a Dirty Harry film and was generally panned by critics. Eastwood began working on smaller, more personal projects, marking a serious lull in his career between 1988 and 1992. He directed Bird (1988), a biopic starring Forest Whitaker as jazz musician Charlie "Bird" Parker, a genre of music that Eastwood has always been personally interested in. Filming commenced in late 1987 and was shot in the old districts of Los Angeles, Pasadena and the Sacramento Valley, with additional New York City scenes shot in Burbank.[34] Bird was screened at Cannes and received a mixed reception. Spike Lee, a long term critic of Eastwood, the son of jazz bassist Bill Lee, and alto saxophonist Jackie McLean criticized the characterisation of Charlie Parker, remarking that it did not capture his true essence and sense of humor.[35] Critic Pauline Kael published a scathing review, confessing to loathing the film and describing it as "a rat's nest of a movie", which looks as if Clint "hadn't paid his Con Ed Bill".[36] Others, particularly jazz enthusiasts,[35] however, praised the music of the film and Eastwood received two Golden Globes—the Cecil B. DeMille Award for his lifelong contribution and the Best Director award for Bird, which also earned him a Golden Palm nomination at the Cannes Film Festival. The film was not a major commercial success, earning just $11 million. Eastwood, who claimed he would have done the film biography even if the script was no good,[37] was disappointed with the commercial reception of the film, later saying that, "We just didn't seem to have enough people in America who wanted to see the story of a black man who in the end betrays his genius. And we didn't get the support through black audiences that I'd hoped for. They really aren't into jazz now, you know. It's all this rap stuff. There aren't enough whites who are. either...".[38]

Carrey would later appear with Eastwood in the poorly received comedy Pink Cadillac (1989) alongside Bernadette Peters. The film is about a bounty hunter and a group of white supremacists chasing after an innocent woman who tries to outrun everyone in her husband's prized pink Cadillac. Pink Cadillac was shot in the fall of 1988 in the Rising River Ranch area and Sacramento.[39] The film was a disaster, both critically and commercially,[40] earning just $12,143,484 and marking the lowest point in Eastwood's career in years, causing concern at Warners that Clint had peaked and was now faltering at the box office after three unsuccessful films.[41] Pink Cadillac received poor reviews. Caryn James wrote: "When it's time to look back on the strange sweep of Clint Eastwood's career, from his ambitious direction of Bird to his coarse, classic Dirty Harry character, Pink Cadillac will probably settle comfortably near the bottom of the list. It is the laziest sort of action comedy, with lumbering chase scenes, a dull-witted script and the charmless pairing of Mr. Eastwood and Bernadette Peters." (New York Times, May 26, 1989.)

Politics

Eastwood made one successful foray into elected politics, becoming the mayor of Carmel-by-the-Sea, California (population 4,000), a wealthy small town and artist community on the Monterey Peninsula, for one term in April 1986.[42] Upon being elected, he was called by President Ronald Reagan asking "What's an actor who once appeared with a monkey in a movie doing in politics?", referring to Eastwood's role in Every Which Way But Loose and Reagan's Bedtime for Bonzo.[42] During Eastwood's tenure, he completed Heartbreak Ridge and Bird.[43]

Bronco Billy (1980)

On Wednesday, June 11th, 1980, Clint Eastwood starred and directed in Bronco Billy. Later on, Bronco Billy (Clint Eastwood) and Antoinette Lily (Sondra Locke) drives a Champagne Metallic 1966 GMC 3500 Custom 2-door pickup truck.

Any Which Way You Can (1980)

Later on Wednesday, December 17th, 1980 he appeared in the movie Any Which Way You Can. Later on, he drives a Dark Maple Red Metallic 1980 Oldsmobile Ninety-Eight Regency 4-door sedan.

Firefox (1982)

The US Navy's team landing, with Clint Eastwood as burned out United States pilot takes care of himself.

Honkytonk Man (1982)

Barry Corbin, who played Red's father in Honkytonk Man, with Clint Eastwood as a country western. Later on, Red Stovall (Clint Eastwood) suffers from tuberculosis at the Grand Ole Opry. He takes out on a stage to Nashville, Tennessee, Clint's son Kyle Eastwood is his nephew.

Sudden Impact (1983)

Dirty Harry Callahan (Clint Eastwood) is one of the year's police detective films. The FBI, after years of investigating. The lines wrote when Clint Eastwood wrote the script for Sudden Impact. "Listen, punk. To me you're nothing but dog shit, understand? And a lot of things can happen to dog shit. It can be scraped up with a shovel off the ground. It can dry up and blow away in the wind and it can be stepped on and squashed. So be careful and take my advice: Be careful when the dog shits you!" - Harry Callahan #4

Tightrope (1984)

Clint Eastwood played a New Orleans detective named Wes Block, is one of the year's police detective films. It was 2 years until Heartbreak Ridge (1986).

City Heat (1984)

The story was pretty routine: taciturn Lieutenant Speer (Clint Eastwood) and his wisecracking partner Mike Murphy (Burt Reynolds). Burt Reynolds broke his jaw when he was hit by a real chair in a fight scene. Despite rumors, he was not punched by Clint Eastwood.

Pale Rider (1985)

In the fact so that he is Clint Eastwood, a comedy western cowboy named Hull Barrett (Michael Moriarty).

Heartbreak Ridge (1986)

The US Navy's USS Belleau Wood (LHA-3) is the view from CH-46 Sea Knights, from which they disembark. They were dropped by helocast into the water of the rest of the Battalion Landing Team, ordering Stitch Jones to use a bulldozer.

See also

References

- ↑ Munn (1992)

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.317

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p.361

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.318

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p.362

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p.365

- 1 2 Maslin, Janet (December 17, 1980). "Any Which Way You Can (1980):Screen:Clint and Clyde". The New York Times.

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.319

- ↑ Maslin, Janet (June 11, 1980). "Bronco Billy (1980):Eastwood Stars and Directs 'Bronco Billy'". The New York Times.

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.344

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.345

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.337

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.352

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p.389

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.361

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p.388

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.365

- 1 2 McGilligan (1999), p.366

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p.393

- ↑ Denby, David (August 27, 1984). Beyond Good and Evil. New York.

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p.394

- ↑ Halbfinger, David M. (September 21, 2006). "The Power of an Image Drives Film by Eastwood". The New York Times. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.371

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.375

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.377

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.378

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.395

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.397

- 1 2 McGilligan (1999), p.398

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.406

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.403

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), pp.410–413

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.407

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.423

- 1 2 McGilligan (1999), p.433

- ↑ Kael, Pauline (October 17, 1988). "Bird Thou Never Went". The New Yorker.

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p.424

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p.435

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.434

- ↑ Schickel (1996), p.442

- ↑ McGilligan (1999), p.437

- 1 2 Eliot (2009), p.227

- ↑ Eastwood website.

Bibliography

- Avery, Kevin (2011). Conversations with Clint: Paul Nelson's Lost Interviews with Clint Eastwood, 1979 - 1983. Continuum Books. ISBN 144116586X.

- McGilligan, Patrick (1999). Clint: The Life and Legend. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-638354-8.

- Schickel, Richard (1996). Clint Eastwood: A Biography. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-42974-6.