History of Manila

| Part of the series on the |

| History of Manila |

|---|

|

| History |

|

| Events |

|

| Other |

|

|

|

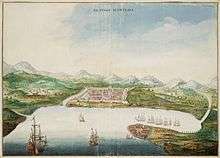

Manilese history begins around 65,000 B.C. the time the Callao Man first settled in the Philippines, predating the arrival of the Negritos and the Malayo-Polynesians. The nearby Angono Petroglyphs, are then dated to be around 3,000 B.C. and the earliest recorded History of Manila, the capital of the Philippines, dates back to the year 900 AD as recorded in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription. By the 13th century, the city consisted of a fortified settlement and trading quarter near the mouth of the Pasig River, the river that bisects the city into north and south. The official name of the city under its Malay aristocracy was Seludong/Selurung, which was the same name given for the general region of southwestern Luzon at that time, suggesting that it was the capital of Ancient Tondo. However, the city became known by the name given to it by its Tagalog inhabitants, Maynila, based on the nilad plant, a flowering mangrove plant that grew on the marshy shores of the Manila Bay.[1]

Manila became the seat of the colonial government of Spain when it gained sovereignty over the Philippine Islands in 1565. The seat of the Spanish government was situated within the fortified walls of Old Manila (now referred to as Intramuros meaning within the walls). The walls were constructed to keep out invading Chinese pirates and protect the city from native uprisings. Several communities eventually grew outside the walls of Manila. The city became the center of trade between Manila and Acapulco, which lasted for three centuries and brought the goods from the Americas to South East Asia and vice versa.

There were a number of raids and invasion attempts made upon Manila during the Spanish period. The twenty month British occupation of the city (1762-1764) came closest to success when the city was held as a base for an attempt to conquer the Philippines, but the defeat of the British campaign resulted in the city being handed back as part of the peace settlement of the Seven Years' War.

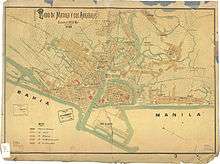

In 1898, Spain ceded control of the Philippines after over three hundred year of colonial rule to the United States after the Treaty of Paris (1898), which ended the Spanish–American War. During the American Period, some semblance of city planning using the architectural designs and master plans by Daniel Burnham was done on the portions of the city south of the Pasig River.

During World War II, much of the city was destroyed, but the city was rebuilt in after the war.[2] It was the second most destroyed city in the world after Warsaw, Poland during World War II. The Metropolitan Manila region was enacted as an independent entity in 1975.

Etymology

The city became known by the name given by its Tagalog inhabitants, as Maynila, first recorded as Maynilad or "Manila". The name is based on the nila, a flowering mangrove plant that grew on the marshy shores of the bay, used to produce soap for regional trade. It is either from the phrase may nila, Tagalog for "there is nila," or it has a prefix ma- indicating the place where something is prevalent. Nila itself is probably from Sanskrit nila (नील) meaning 'indigo tree'.[3] The idea that the plant name is actually "nilad" is baseless.[4]

History

Prehistory and indigenous civilizations

Under the Malay aristocracy, the city was known as Seludong/Selurung, which was the same name given for the general region of southwestern Luzon at that time, suggesting that it was the capital of Ancient Tondo. It was also known as Gintu ("The Land/Island of Gold") or Suvarnadvipa by its neighbors. The said kingdom flourished during the latter half of the Ming Dynasty as a result of trade relations with China.[5] Ancient Tondo has always been the traditional capital of the empire. Its rulers were equivalents to kings and not mere chieftains, and they were addressed as panginuan or panginoon ("lords"), anak banwa ("son of heaven") or lakandula ("lord of the palace"). Well into the 13th century, the city consisted of a fortified settlement and trading quarter at the bay of the Pasig River, on top of previous older towns.

| Historical Affiliations |

|---|

Rise of the Kingdom of Luzon

In the year 900 the Kingdom of Luzon, which is otherwise known as the Dynasty of Tondo centered in Manila Bay, flourished via an active trade with Chinese sea traders in the area, later serving as a smuggling nexus after the Chinese imposed restrictions on their foreign trade.[6] During this time, the lord-minister Jayadewa presented a document of debt forgiveness to Lady Angkatan and her brother Bukah, the children of Namwaran. This is described in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, the Philippines' oldest recorded document.[7] This inscription shows the possible link between the ancient Philippines and the Medang Kingdom of Java.

As a province of Majapahit

In the 14th century there is evidence of Manila being a province of the Indonesian Hindu empire of Majapahit due to the epic eulogy poem Nagarakretagama, which was dedicated to Maharaja Hayam Wuruk. Seludong/Selurung was listed in Canto 14 alongside Sulot (Sulu) and Kalka.[8]

The Conquest of Sultan Bulkiah from Brunei

During the reign of Sultan Bolkiah in 1485 to 1521, the Sultanate of Brunei decided to break the Dynasty of Tondo's monopoly in the China trade by attacking Tondo and establishing the state of Selurung as a Bruneian satellite-state.[9][10] A new dynasty under the Islamized Rajah Salalila[11] was also established to challenge the House of Lakandula in Tondo.[12] Islam was further strengthened by the arrival to the Philippines of traders and proselytizers from Malaysia and Indonesia.[13] The multiple states competing over the limited territory and people of the islands simplified Spanish colonization by allowing its conquistadors to effectively employ a strategy of divide and conquer for rapid conquest.

Warring cities period

In the mid-16th century, the areas of present-day Manila were part of larger thalassocracies governed by Muslim Rajahs. Rajah Sulayman and Rajah Matanda ruled the Muslim communities south of the Pasig River, and Lakan Dula ruled the Kingdom of Tondo, the Hindu-Buddhist community north of the river. The two Muslim communities of Sulayman and Matanda were unified into the Kingdom of Maynila. Both city-states were officially Malay-speaking and held diplomatic ties with the Bolkiah dynasty of Brunei and the sultanates of Sulu and Ternate (not to be confused with Ternate, Cavite).

Spanish period

Spanish rule 1571-1762

Governor-General Miguel López de Legazpi, searching for a suitable place to establish his capital after being compelled to move from Cebu to Panay by Portuguese pirates, and hearing of the existence of prosperous kingdoms in Luzon, sent an expedition under Marshal Martin de Goiti and Captain Juan de Salcedo to discover its location and potential. De Goiti anchored at Cavite, and attempted to establish his authority peacefully by sending a message of friendship to Maynilad. Rajah Sulayman, then its ruler, was willing to accept the friendship that the Spaniards were offering, but did not want to submit to its sovereignty unto them and waged war against them.[14] As a result, De Goiti and his army attacked Maynilad in June 1570. After a stout fight, he captured the city before returning to Panay.

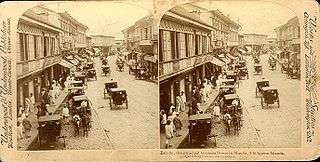

In 1571, the unity of the Luzon Empire was already threatened by the uneasy alliance of the Rajah Matanda of Sapa, Lakan Dula of Tondo, and Rajah Sulayman, the rajah muda or "crown prince" of Maynila and laxamana or "grand admiral" of the Macabebe Armada. Powerful states like Lubao, Betis and Macabebe became bold enough to challenge the traditional leadership of Tondo and Maynila.[5] In about the same year, the Spaniards returned, this time led by López de Legazpi himself along with his entire force (consisting of 280 Spaniards and 600 native allies). Seeing them approach, the natives set the city on fire and fled to ancient Tondo and neighboring towns. The Spaniards occupied the ruins of Maynilad and established a settlement there. On May 19, 1571, López de Legazpi gave the title city to the colony of Manila.[15] The title was certified on June 19, 1572.[15] Under Spain, Manila became the colonial entrepot in the Far East. The Philippines was a Spanish colony administered under the Viceroyalty of New Spain and the Governor-General of the Philippines who ruled from Manila was sub-ordinate to the Viceroy in Mexico City.[16] The Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade route between the Philippines and Mexico flourished from 1571 until 1815.[17] Manila became famous during the Manila-Acapulco trade which brought the goods as far as Mexico all the way to Southeast Asia.

Because of the Spanish presence in the area, the Chinese people, who were living in the area and engaging in free trade relations with the natives, were subjected to commercial restrictions as well as laws requiring them to pay tribute to Spanish authorities. As a result, the Chinese revolted against the Spaniards in 1574, when a force of about 3,000 men and 62 Chinese warships under the command of Limahong attacked the city. The said attempt was fruitless, and the Chinese were defeated. In order to safeguard the city from similar uprisings later, the Spanish authorities confined the Chinese residents and merchants to a separate district called Parian de Alcaceria.[18]

On June 19, 1591, after the commencement of the construction of a fort there, López de Legazpi made overtures of friendship with Lakan Dula of Tondo, which was prudently accepted. However, Rajah Sulayman refused to submit to the Spaniards and gathered together a force composed of Tagalog warriors after failing to get the support of Lakan Dula and that of the leaders of Hagonoy and Macabebe. On June 3, 1571,[19] Sulayman led his troops and attacked the Spaniards in a decisive battle at the town of Bangkusay, but were defeated. With the destruction of Sulayman's army and the friendship with Lakan Dula, the Spaniards began to establish themselves throughout the city and its neighboring towns. Then came the rapid Christianization of the city. The first missionaries to arrive were the Augustinians, followed by the Franciscans, Jesuits, Dominicans, Augustinians and other religious orders. The friars also began to establish schools and churches dedicated to the Christian faith, eventually spreading throughout Manila and beyond.

In 1595, Manila was decreed to be the capital of the Philippines, although it had already in fact served that function practically from its founding in 1571. Legazpi then ordered the creation of a municipal government or cabildo with a set of Spanish-style houses, monasteries, nunneries, churches, and schools giving birth to Intramuros. The layout of the city was haphazardly planned during this era as a set of communities surrounding the fortified walls of Intramuros (within the walls), which was the original Manila. Intramuros, one of the oldest walled cities in the Far East, was constructed and designed by Spanish Jesuit missionaries to provide protection from invading Chinese pirates and native uprisings.

At various times in the following century, the Chinese rose in revolt against the Spaniards. In 1602, they set fire to Quiapo and Tondo, and for a time threatened to capture Intramuros. In 1662, they again revolted, while in 1686, a conspiracy led by Tingco plotted to kill all the Spaniards. These events led to the expulsion of the Chinese from Manila and the entire country by virtue of the decrees that were made by the Spanish authorities to that effect. However, later reconciliations nearly always permitted the continuation of the Chinese community in the city.

Approximate locations of the towns of the province of Manila

British occupation (1762–64)

There was a British occupation of Manila from 1762–64 as a result of the Seven Years' War. Spain became Britain's enemy when it sided with France due to ties between their royal families. In the ensuing sack of the town by the British, many historical documents of great value were destroyed or stolen from the archives.

The British accepted the written surrender of the Philippines from Archbishop Rojo and the Real Audiencia on 30 October 1762.[20] The terms of surrender proposed by Archbishop Rojo and agreed to by the British leaders, secured private property, guaranteed the Roman Catholic religion and its episcopal government, and granted the citizens of the former Spanish colony the rights of peaceful travel and of trade 'as British subjects'. Under the direction of the provisional British governor, the Philippines was to be governed by the Audencia Real, the expenses of which were agreed to be paid for by Spain.[20] The terms of surrender dated 29 October 1762 signed by Archbishop Rojo, and sealed with the Spanish Royal Seal, ceding the entire archipelago to Great Britain. This was rejected by Simón de Anda y Salazar who claimed to have been appointed Governor-General under the Statutes of the Indies.[21]

The armed resistance to the British began in Pampanga where Anda established his headquarters, first in Bulacan, then in Bacolor. He raised an army of 10 000 Filipinos and re-established Spanish authority over the Philippines, crushing British supported insurrections.[22]

The Seven Years' War was ended by the Peace of Paris signed on 10 February 1763. At the time of signing the treaty, the signatories were not aware that Manila had been taken by the British and was being administered as a British colony. Consequently, no specific provision was made for the Philippines. Instead they fell under the general provision that all other lands not otherwise provided for be returned to the Spanish Crown.[23]

An unknown number of Indian soldiers known as sepoys, who came with the British, deserted and settled in Cainta, Rizal, which explains the uniquely Indian features of generations of Cainta residents.[24]

In January 1798 during the French Revolutionary Wars a British naval squadron entered Manila for reconnaissance, seizing three gunboats in the bloodless Raid on Manila.

Spanish rule 1764-1898

Mexican Independence in 1821 necessitated direct rule from Spain.[25] Under direct Spanish rule, banking, industry and education flourished more than it had in the previous two centuries.[26] The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 facilitated direct trade and communications with Spain.

Being the traditional seat of education and liberal thinking in the Philippines, Manila was a rich field for anticlerical propaganda. The seeds of revolution germinated in 1886 with the publication of José Rizal's book Noli Me Tangere (Touch Me Not), a novel critical of the way the Spanish friars were governing the Philippines. The Spanish government condemned the book, and Rizal was exiled to Dapitan. In 1892, he returned to Manila to found La Liga Filipina, a nationalistic organization. Later that year, in Tondo, Andrés Bonifacio founded the Katipunan, a secret organization with aim of overthrowing Spanish colonial rule.

The Katipunan movement grew until open rebellion broke out in August 1896 after its discovery by the Spaniards. Bonifacio's attack on Manila was unsuccessful. Rizal became a martyr of the revolution when the Spaniards executed him by firing squad on December 30, 1896 in Bagumbayan. After several months of fighting, a revolutionary government was formed at the Tejeros Convention in Cavite province with Emilio Aguinaldo at its head. Aguinaldo's government was also unsuccessful in its fight for independence, and as part of the Pact of Biak-na-Bato peace treaty, Aguinaldo accepted exile in Hong Kong.

American period (1898–1942)

U.S. Troops invaded Manila in 1898 and waged war with the Spaniards and Filipinos in the Spanish–American War and the Philippine–American War. Following the defeat of Spain, U.S. forces took control of the city and the islands in one of the most brutal and forgotten chapters of Philippine American history.

The American Navy, under Admiral George Dewey, defeated the Spanish squadron in the Battle of Manila Bay on May 1, 1898.[27]

During the Battle of Manila the Americans took control of Manila from the Spanish. Admiral Dewey testified that after the battle the Spanish Governor wished to surrender to the Americans rather than the Filipinos.

In the Treaty of Paris in 1898, Spain handed over the Philippines to the United States of America for US$ 20,000,000 and ending 333 years of Spanish rule in the islands.[28][29]

Having just won their independence from Spain, the Filipinos were fiercely opposed to once again being occupied. Emilio Aguinaldo proclaimed the First Philippine Republic at the Malolos Congress and had begun to build the foundations for an independent nation. Admiral Dewey, however, claimed he never recognized the Philippine Republic, as he did not have the authority to do so and did not consider it an organized government.[30]

War broke out between the Filipinos and the Americans on February 4, 1899, the 1899 Battle of Manila, which began the Philippine–American War. The Americans pursued the retreating Filipino forces province by province, until General Emilio Aguinaldo (then president of the Republic) surrendered in Palanan, Isabela, on March 23, 1901.

Manila continued under an American military government until civil government was established for the city on July 31, 1901.

During the American Period, some semblance of city planning using the architectural designs and master plans by Daniel Burnham was done on the portions of the city south of the Pasig River.

In 1935, the United States government committed itself to granting the Philippines Independence after a ten-year transition, a period that was extended by one year due to World War II. The establishment of the General Headquarters of the Philippine Commonwealth Army was stationed in the capital city in Ermita, Manila under the Commonwealth government was active on December 21, 1935 to January 3, 1942 was followed by the Japanese Occupation and March 4, 1945 to June 30, 1946 after the liberating Battle of Manila.

World War II and Japanese occupation

Reconstructed and is now a part of the National Museum

Filipino and American combat units were ordered to withdraw from the city and all military installations removed on December 24, 1941 (Philippine time). That same day, Manila was declared an open city to spare the city from death and destruction.[31] Despite this, the Japanese warplanes bombed Manila and for the first time, Manileños experienced the first air raid.[32] Quezon issued a decree enlarging the safe zone to include outlying areas of Manila as safe zones, establishing the new administrative jurisdiction, Greater Manila.

The mainly general headquarters of the Philippine Commonwealth Army was withdrawn and retreated to the military stations in Ermita, Manila. On December 24 1941, they are closed down following the arrival and occupation of the capital city by the Japanese Imperial forces, who took control of the main general headquarters of the Commonwealth Army on January 3, 1942. Following the Japanese Occupation, the general headquarters and military camps and bases of the Philippine Commonwealth Army are used around the provinces of the Philippine Archipelago from Luzon, Visayas and aMindanao from January 3, 1942 to June 30, 1946 has openly the service and began the local military conflicts against the Japanese Occupation in this country.

The post of mayor of Greater Manila was given to Quezon's former Executive Secretary, Jorge B. Vargas. On the evening of New Year's Day of 1942, a Japanese courier delivered notice to Vargas that Japanese forces already bivouacked at Parañaque would enter Greater Manila the following day. From 9 am to 10 am of January 2, Japanese imperial forces marched into the City of Manila.

Vargas was tasked to hand over Greater Manila to the new authorities and present the remaining Filipino leaders to Japanese authorities. Vargas and the Filipino leaders present were asked to choose three options; (1) a purely Japanese military administration, (2) a dictatorial government run by a Filipino under General Artemio Ricarte who went on self-exile to Japan after the Filipino-American war, or (3) a government by commission selected by Filipinos. Vargas and the local leaders chose the third option and established the Philippine Executive Commission to manage initially Greater Manila, and was later expanded to cover the whole of the Philippines.

Vargas assumed the chairmanship of the Philippine Executive Commission and appointed to the post of Mayor of Greater Manila in 1942, Leon G. Guinto Sr., a Secretary of Labour under the Philippine Commonwealth administration of President Manuel L. Quezon. Guinto held the position of Mayor of Greater Manila until the liberation of the city.

On October 20, 1944, American and Philippine Commonwealth troops, led by American General Douglas MacArthur, began the reconquest of the Philippines. Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita ordered the commander of Shimbu Group, Gen. Shizuo Yokoyama, to destroy all bridges and other vital installations and evacuate the city. However, units of the Imperial Japanese Navy, led by Sanji Iwabuchi, refused to leave the city. Thus, from February 3 to March 3, 1945, much of the city was destroyed during the Battle of Manila and 100,000 to 500,000 civilians were killed during the Manila Massacre. Almost 85,000 to 140,000 strong Filipino soldiers and military officers under the Philippine Commonwealth Army send the military operations around Manila from the mainly general headquarters of the Commonwealth Army in Central and Southern Luzon was aided of all 3,000 guerrilla fighters and 35,000 American liberation forces was prepare the attack around the capital city by the Imperial Japanese Marines and Army troops. As a result of these events in World War II, Manila was the second most destroyed city in the world after Warsaw, Poland during World War II. Once Manila was officially liberated, the rebuilt of the general headquarters of the Philippine Commonwealth Army with the Philippine Constabulary was relocated of the capital city on March 4, 1945 to June 30, 1946 after the liberation and prepares the engagements of the military operations in Luzon against the Japanese and helps Americans and guerrillas, Greater Manila was dissolved, and its towns returned to their pre-war status. On July 4, 1946, the Philippine flag was raised for the first time in Rizal Park. Reconstruction took place during the years following WWII.

Contemporary period

The Golden Age and the Marcos Era (1952 to 1986)

With Arsenio Lacson becoming the first elected mayor in 1952 (all mayors were appointed prior to this), the City of Manila underwent The Golden Age,[33] was revitalized, and once again became the "Pearl of the Orient", a moniker it earned before the outbreak of the war.

After Mayor Lacson's successful term in the fifties, the city was led by Mayor Antonio Villegas during most of the 60's, and Mayor Ramon Bagatsing for nearly the entire decade of the 70's until the 1986 Edsa revolution, making him the longest serving Mayor of Manila.

Mayors Lacson, Villegas, and Bagatsing are most often collectively referred to as "the Big Three of Manila" for their rather long tenures as chief executive of City Hall (continuously for over three decades, from 1952–1986), but more importantly, for their impeccable contribution to the development and progress of the City and their lasting legacy in uplifting the quality of life and welfare of the people of Manila.

During the Marcos Era, the region of the Manila Metropolitan area was enacted as an independent entity in 1975 encompassing several cities and towns, being a separate local-regional unit and the seat of government of the Philippines.

Fifth Republic (1986–present)

After the People Power Revolution, Aquino's widow, Corazon, was installed as president in 1986. During the Aquino presidency, Manila witnessed six unsuccessful coup attempts, the most serious occurring in December 1989.[34]

In 1992, Alfredo Lim became the mayor, and was known for his anti-crime crusades. When Lim ran for the presidency during the 1998 presidential election, his vice mayor Lito Atienza was elected as city mayor. Atienza was known for renovating most of the city's plaza, and projects that would benefit the populace. He was the Mayor of Manila for 3 terms (9 years); barred for seeking a fourth consecutive term. Lim defeated Atienza's son Ali in the 2007 city election and immediately reversed all of Atienza's projects[35] claiming the projects made little contribution to the improvements of the city. On July 17, 2008, councilor Dennis Alcoreza filed human rights complaints before the Commission on Human Rights, against Lim, and other Manila officials.[36] Twenty-four Manila officials also resigned because of the maltreatment of Lim's police forces. The relationship of both parties turned bitter, with the two pitting again during the 2010 city elections in which Lim won against Atienza.

Among the numerous controversies surrounding Lim's administration were the filing of human rights complaints against him and other city officials by councilor Dennis Alcoreza on 2008,[37] the resignation of 24 city officials because of the maltreatment of Lim's police forces, and his bloody resolution of the Manila hostage crisis, one of the deadliest hostage crisis in the Philippines. Lim was also accused of graft and corruption,[38] believed to be the cause of the city's bankruptcy. These allegations were later followed by a complaint in 2012 by Vice Mayor Isko Moreno and 28 city councilors which cited that Lim's statement in a meeting were "life-threatening" to them.[39][40] During the 2013 elections, former President Joseph Estrada defeated Lim in the mayoral race.

Historical Battles

The first two recorded battles in Manila occurred in 1365 in which Maharaja Hayam Wuruk invaded the kingdom of Selurong, followed by the subjugation of the Kingdom of Tondo by Sultan Bolkiah of Brunei caused moderate damage to the city.[41] It was followed by another battle in 1571, wherein the conquistador Martin de Goiti arrived from Mexico to drive out the Muslim elite, and the city was razed to the ground.[42] It explains the absence of any pre-Hispanic architecture in Manila. The battle of Manila in 1574, between Chinese pirate-warlord Limahong and Don Galo only produced minimal damage to Manila.[43]

After the battle and occupation of Manila by Britain in 1762, the city was pillaged for 40 hours. The next two consecutive battles for Manila; the battle in 1896 and the battle in 1898 did little damage to the city as whole. The battle of 1899, the first battle of the Philippine–American War, caused more than 200 Filipino casualties.

During the battle of Manila in 1945 between the Japanese Empire and the Allied forces, some 100,000 to 500,000 of Manila's civilians were killed by the Japanese troops in Manila massacre. The whole city was devastated, erasing its cultural and historic identity, including the destruction of the walled city of Intramuros. Reconstruction of the city took place afterwards, with some of Manila's landmarks restored.

References

- ↑ Ardery, Julie. "Q. What's in Manila's Name? A. White Star-Shaped Flowers". Human flower project. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ↑ City Profiles: Manila, Philippines. UN Cyberbus. Accessed February 02, 2009.

- ↑ E.M. Pospelov, Geograficheskie nazvanie mira (Географические название мира) (Moscow 1998).

- ↑ Ambeth Ocampo (June 25, 2008), "Looking Back: Pre-Spanish Manila", Philippine Daily Inquirer, retrieved 2008-09-09

- 1 2 San Agustin, Gaspar de, Conquistas de las Islas Philipinas 1565-1615, Translated by Luis Antonio Mañeru, 1st bilingual ed [Spanish and English], published by Pedro Galende, OSA: Intramuros, Manila, 1998

- ↑ 明史

- ↑ The Laguna Copperplate Inscription, 2006-07-14, retrieved 2008-02-05

- ↑ Gerini, G. E. (1905). "The Nagarakretagama List of Countries on the Indo-Chinese Mainland (Circâ 1380 A.D.)". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland: 485–511. doi:10.2307/25210168. JSTOR 25210168.

- ↑ Scott 1984

- ↑ Pusat Sejarah Brunei. Retrieved February 07, 2009.

- ↑ Santiago, Luciano P.R., "The Houses of Lakandula, Matanda, and Soliman [1571-1898]: Genealogy and Group Identity," Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society, 18 [1990]

- ↑ Henson, Mariano A. 1965. The Province of Pampanga and Its Towns: A.D. 1300–1965. 4th ed. revised. Angeles City: By the author.

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, p. 22

- ↑ Filipiniana: Act of Taking Possession of Luzon by Martin de Goiti. Accessed September 06, 2008.

- 1 2 Blair 1911, pp. 173–174

- ↑ The Philippines was an autonomous Captaincy-General under the Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1521 until 1815

- ↑ The Manila Galleon Trade. The Metropolitan Museum of Manila. Accessed February 07, 2009.

- ↑ History of the Philippine Islands by Dr. Antonio de Morga. Accessed January 24, 2009.

- ↑ History of Manila. Accessed September 08, 2008.

- 1 2 Tracy 1995, p. 54

- ↑ Fish 2003, p. 134

- ↑ Tracy 1995, p. 58

- ↑ Tracy 1995, p. 109

- ↑ Fish 2003, p. 158

- ↑ Fundación Santa María (Madrid) 1994, p. 508

- ↑ John Bowring, "Travels in the Philippines", p. 18, London, 1875

- ↑ Battle of Manila Bay, 1 May 1898. Accessed September 08, 2008.

- ↑ "Philippines, The", The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-07, bartleby.com, retrieved 2009-05-14

- ↑ Philippine History, Pinas, De La Salle University, retrieved 2009-05-14 External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Admiral Dewey Testifies. Accessed September 05, 2008.

- ↑ Paul P. Rogers (1990), The good years: MacArthur and Sutherland, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 118, ISBN 978-0-275-92918-3

- ↑ The Plane Bombings

- ↑ Hancock 2000, p. 16

- ↑ MSN Encarta: Manila. Accessed September 06, 2008. Archived 2009-11-01.

- ↑ Mundo, Sheryl (2009-12-01). "It's Atienza vs. Lim Part 2 in Manila". Manila: ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

Environment Secretary Jose 'Lito' Atienza will get to tangle again with incumbent Manila Alfredo Lim in the coming 2010 elections.

- ↑ Legaspi, Amita (17-07-08). "Councilor files raps vs Lim, Manila execs before CHR". GMA News. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

A Manila City councilor on Thursday filed human rights complaints against Mayor Alfredo Lim, other city officials and policemen over the violent takeover of the Dealco slaughterhouse in Vitas, Tondo last July 11.

Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ Legaspi, Amita (July 17, 2008). "Councilor files raps vs Lim, Manila execs before CHR". GMA News. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

A Manila City councilor on Thursday filed human rights complaints against Mayor Alfredo Lim, other city officials and policemen over the violent takeover of the Dealco slaughterhouse in Vitas, Tondo last July 11.

- ↑ "Mayor Lim charged anew with graft over rehabilitation of public schools". The Daily Tribune. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ Jenny F. Manongdo (June 23, 2012). "Isko, 28 Dads Rap Lim; Mayor Strikes Back". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ "Isko Moreno, 28 councilors file complaint vs Lim". ABS-CBN News and Current Affairs. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ History for Brunei 2009, p. 41

- ↑ Relation of the Voyage in Luzon sa Blair & Robertson. The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803;Volume III, 1569-1576.

- ↑ Stearn, Duncan, Chronology of South-East Asian History 1400-1996 (Dee Why, NSW: The Mitraphab Centre Pty Ltd., 1997).

External links

Sources

- Bayor, Ronald H (June 23, 2004), The Columbia Documentary History of Race and Ethnicity in America, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-11994-1, retrieved 2009-05-14.

- Blair, Emma Helen, ed. (1911), The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803, (Vol. 1, no. 3).

- Boot, Max (April 1, 2002), The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-00720-1, LCCN 2004695066, retrieved 2009-05-14.

- Fish, Shirley (2003), When Britain Ruled the Philippines 1762–1764, Bloomington, Ind.: 1st Book Library, ISBN 1-4107-1069-6.

- Kumar, Amitava (October 29, 1999), Poetics/Politics: Radical Aesthetics for the Classroom, Palgrave, ISBN 0-312-21866-4, retrieved 2009-05-14.

- Painter, Nell Irvin (May 1, 1989), Standing at Armageddon: The United States, 1877–1919, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-30588-0, retrieved 2009-05-14.

- Tracy, Nicholas (1995), Manila Ransomed: The British Assault on Manila in the Seven Years' War, University of Exeter Press, ISBN 978-0-85989-426-5, retrieved 2009-05-14 ISBN 0-85989-426-6, ISBN 978-0-85989-426-5

Further reading

- Published in the 19th century

- William Milburn; Thomas Thornton (1825). "Manilla". Oriental Commerce; or the East India Trader's Complete Guide. London: Kingsbury, Parbury, and Allen.

- Margherita Arlina Hamm (1898), Manila and the Philippines, London: F.T. Neely

- John Foreman (1899), "(Manila)", The Philippine Islands (2nd ed.), New York: C. Scribner's Sons

- Manila and the Philippine Islands: an up to date handbook of facts, New York: Philippines Company, 1899

- Published in the 20th century

- Commercial Directory of Manila, Manila, 1901

- Burton Holmes (1901), "Manila", The Burton Holmes Lectures, Battle Creek, Michigan: Little-Preston, OCLC 5082081

- Historical Notes Concerning Manila. United States government. 1904.

- Kemlein & Johnson's Guide and Map of Manila and Vicinity. 1908.

- Manila, the pearl of the Orient, Manila, Philippine Islands: Manila Merchants' Association, 1908, OCLC 5296360

- "Manila", Encyclopaedia Britannica (11th ed.), New York: Encyclopaedia Britannica Co., 1910, OCLC 14782424

- Philippines. Office of Public Welfare Commissioner. (1922), Directory of charitable and social service organizations and institutions in the city of Manila (2nd ed.), Manila: Bureau of Printing