Vaccination policy

Vaccination policy refers to the health policy a government adopts in relation to vaccination. Vaccinations are voluntary in some countries and mandatory in others, as part of their public health system. Some governments pay all or part of the costs of vaccinations for vaccines in a national vaccination schedule.

Goals of vaccination policies

Immunity and herd immunity

Vaccination policies aim to produce immunity to preventable diseases. Besides individual protection from getting ill, some vaccination policies also aim to provide the community as a whole with herd immunity. Herd immunity refers to the idea that the pathogen will have trouble spreading when a significant part of the population has immunity against it. This protects those unable to get the vaccine due to health reasons, such as age, allergies and having received an organ transplant.

Each year, vaccination averts between two and three million deaths, across all age groups, from diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and measles.[1] These diseases used to be among the leading causes of death worldwide. Now, many of these deaths are able to be avoided.

The impact of immunization policy on vaccine-preventable diseases has been listed as one of the top public health achievements.[2][3]

Eradication of disease

With some vaccines, a goal of vaccination policies is to eradicate the disease - make it disappear from Earth altogether. The World Health Organization coordinated the global effort to eradicate smallpox globally. Victory is also claimed for getting rid of endemic measles, mumps and rubella in Finland. The last naturally occurring case of smallpox occurred in Somalia in 1977. In 1988, the governing body of WHO targeted polio for eradication by the year 2000, but didn't succeed. The next eradication target would most likely be measles, which has declined since the introduction of measles vaccination in 1963.

Individual versus group goals

Rational individuals will attempt to minimize the risk of illness, and will seek vaccination for themselves or their children if they perceive a high threat of disease and a low risk to vaccination. However, if a vaccination program successfully reduces the disease threat, it may reduce the perceived risk of disease enough so that an individual's optimal strategy is to encourage everyone but their family to be vaccinated, or (more generally) to refuse vaccination at coverage levels below those optimal for the community.[4] For example, a 2003 study found that a bioterrorist attack using smallpox would result in conditions where voluntary vaccination would be unlikely to reach the optimum level for the U.S. as a whole,[5] and a 2007 study found that severe influenza epidemics cannot be prevented by voluntary vaccination without offering certain incentives.[6] Governments often allow exemptions to mandatory vaccinations for religious or philosophical reasons, but some believe that decreased rates of vaccination may cause loss of herd immunity, substantially increasing risks even to vaccinated individuals.[7]

Compulsory vaccination

To eliminate the risk of disease outbreaks, at various times governments and other institutions established policies requiring vaccination. For example, an 1853 law required universal vaccination against smallpox in England and Wales, with fines levied on people who did not comply.[8] In the United States, the Supreme Court ruled in Jacobson v. Massachusetts (1905) that states could compel vaccination for the common good. Contemporary U.S. policies usually require children receive vaccinations before entering school, although many states allow for religious and personal exemptions due to philosophical or health reasons. A few other countries also follow this practice. Compulsory vaccination greatly reduces infection rates for associated diseases.[8] Beginning with nineteenth century early vaccination, these policies stirred resistance from a variety of groups, collectively called anti-vaccinationists, who objected on ethical, political, medical safety, religious, and other grounds. Common objections included claims of "excessive government intervention in personal matters" or that proposed vaccinations were not sufficiently safe. Many modern vaccination policies allow exemptions for people with compromised immune systems, allergies to vaccination components, or strongly held objections.[9]

In 1904 in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, following an urban renewal program that displaced many poor, a government program of mandatory smallpox vaccination triggered the Vaccine Revolt, several days of rioting with considerable property damage and a number of deaths.[10]

Compulsory vaccination is a difficult policy issue, requiring authorities to balance public health with individual liberty:

"Vaccination is unique among de facto mandatory requirements in the modern era, requiring individuals to accept the injection of a medicine or medicinal agent into their bodies, and it has provoked a spirited opposition. This opposition began with the first vaccinations, has not ceased, and probably never will. From this realisation arises a difficult issue: how should the mainstream medical authorities approach the anti-vaccination movement? A passive reaction could be construed as endangering the health of society, whereas a heavy-handed approach can threaten the values of individual liberty and freedom of expression that we cherish."[11]

Investigation of different types of vaccination policy finds strong evidence for the effectiveness of standing orders, allowing healthcare workers without prescription authority (such as nurses) to administer vaccines in defined circumstances; sufficient evidence for the effectiveness of requiring vaccinations before attending child care and school;[12] and insufficient evidence to assess effectiveness of requiring vaccinations as a condition for hospital and other healthcare jobs.[13]

Evaluating vaccination policy

Vaccines as a positive externality

The promotion of high levels of vaccination produces the protective effect of herd immunity as well as positive externalities in society.[14] Vaccinations are public goods, they are both non-rivalrous and non-excludable, and given these traits, individuals may avoid the costs of vaccination by "free-riding"[14] off the benefits of others being vaccinated.[14][15][16] The costs and benefits to individuals and society have been studied and critiqued in stable and changing population designs.[17][18][19] Other surveys have indicated that free-riding incentives exist in individual decisions,[20] and in a separate study that looked a parental vaccination choice, the study found that parents were less likely to vaccinate their children if their children's friends had already been vaccinated.[21] The free-rider problem inherent to vaccinations as a public good is important to public health policy makers when assessing policy options.

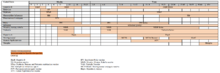

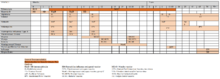

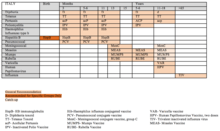

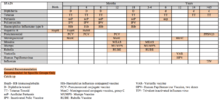

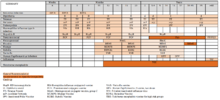

Cost-benefit analysis for population-level vaccination programs—United States

Since the first economic analysis of routine childhood immunizations in the United States in 2001 that reported cost savings over the lifetime of children born in 2001,[22] other analyses of the economic costs and potential benefits to individuals and society have since been studied, evaluated, and calculated.[14][23] In 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a decision analysis that evaluated direct costs (program costs such as vaccine cost, administrative burden, negative vaccine-linked reactions, and transportation time lost to parents to seek health providers for vaccination).[23] The study focused on diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, Haemophilus influenza type b conjugate, poliovirus, measles/mumps/rubella (MMR), hepatitis B, varicella, 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate, hepatitis A, and rotavirus vaccines, but excluded influenza. Estimated costs and benefits were adjusted to 2009 dollars and projected over time at 3% annual interest rate.[23] Of the theoretical group of 4,261,494 babies beginning in 2009, that had regular immunizations through childhood in accordance with the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices guidelines "will prevent ∼42 000 early deaths and 20 million cases of disease, with net savings of $13.5 billion in direct costs and $68.8 billion in total societal costs, respectively." [23] In the United States, and in other nations,[24][25][26] there is an economic incentive and "global value" to invest in preventive vaccination programs, especially in children as a means to prevent early infant and childhood deaths.[27]

Policies and history by country

In 2006, the World Health Organization and UNICEF created the Global Immunization Vision and Strategy (GIVS). This organization created a ten-year strategy with four main goals:[28]

- to immunize more people against more diseases

- to introduce a range of newly available vaccines and technologies

- to integrate other critical health interventions with immunization

- to manage vaccination programmes within the context of global interdependence

The Global Vaccination Action Plan was created by the World Health Organization and endorsed by the World Health Assembly in 2012. The plan which is set from 2011-2020 is intended to "strengthen routine immunization to meet vaccination coverage targets; accelerate control of vaccine-preventable diseases with polio eradication as the first milestone; introduce new and improved vaccines and spur research and development for the next generation of vaccines and technologies".[29]

These global actions are telling to the progression of vaccinations. Living in a globalized world that is extremely connected, diseases that are preventable by vaccinations have become part of a larger public health movement: global herd immunity. These task forces and political campaigns that have erected in order to spread availability and knowledge of vaccination are modern attempts to protect the world from vaccination-preventable diseases.

Australia

In an effort to boost vaccination rates in Australia, the Australian government has decided that from 1 January 2016, certain benefits (such as the universal 'Family Allowance' welfare payments for parents of children) will no longer be available for conscientious objectors of vaccination; those with medical grounds for not vaccinating will continue to receive such benefits. The policy is supported by a majority of Australian parents as well as the Australian Medical Association (AMA) and Early Childhood Australia. In 2014, about 97 percent of children under 7 years have been vaccinated, though the number of conscientious objectors to vaccination have increased greatly.[30]

It has also been suggested to limit children's entry into school unless they were either vaccinated or their parents completed a statutory declaration refusing to immunise them, after discussion with a doctor. (Similar school-entry vaccination regulations have been in place in some parts of Canada for several years.)

The government began the Immunise Australia Program to increase national immunisation rates.[31] They fund a number of different vaccinations for certain groups of people. The intent is to encourage the most at-risk populations to get vaccinated.[32] The government maintains an immunization schedule.[33]

Republic of Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland, childhood vaccination (up to age 16) requires the consent of the parents. The Department of Health strongly recommend vaccinations.[34]

Malaysia

In Malaysia, mass vaccination is practised in public schools. The vaccines may be administered by a school nurse or a team of other medical staff from outside the school. All the children in a given school year are vaccinated as a cohort. For example, children may receive the oral polio vaccine in Year One of primary school (about six or seven years of age), the BCG in Year Six, and the MMR in Form Three of secondary school. Therefore, most people have received their core vaccines by the time they finish secondary school.[35]

Slovenia

According to a 2011 publication in CMAJ:[36]

Slovenia has one of the world's most aggressive and comprehensive vaccination programs. Its program is mandatory for nine designated diseases. Within the first three months of life, infants must be vaccinated for tuberculosis, tetanus, polio, pertussis, and Haemophilus influenza type B. Within 18 months, vaccines are required for measles, mumps and rubella, and finally, before a child starts school, the child must be vaccinated for hepatitis B.

While a medical exemption request can be submitted to a committee, such an application for reasons of religion or conscience would not be acceptable.

Failure to comply results in a fine and compliance rates top 95%, Kraigher says, adding that for nonmandatory vaccines, such as the one for human papilloma virus, coverage is below 50%.

Mandatory vaccination against measles was introduced in 1968 and since 1978, all children receive two doses of vaccine with a compliance rate of more than 95%.[37] For TBE, the vaccination rate in 2007 was estimated to be 12.4% of the general population in 2007. For comparison, in neighboring Austria, 87% of the population is vaccinated against TBE.[38]

Pakistan

The Pakistani government in 2014 following a multitude of minor polio epidemics has now ruled that the polio vaccination is mandatory and indisputable. In a statement from Pakistanis police commissioner Riaz Khan Mehsud "There is no mercy, we have decided to deal with the refusal cases with iron hands. Anyone who refuses [the vaccine] will be sent to jail".

South Africa

The South African Vaccination and Immunisation Centre began in 2003 as an alliance between the South African Department of Health, vaccine industry, academic institutions and other stakeholders.[39] SAIVC works with WHO and the South African National Department of Health to educate, do research, provide technical support, and advocate. They work to increase rates of vaccination in order to improve the nation's health.

Latvia

According to a 2011 publication in CMAJ:[36]

Some nations, such as Latvia, say they have mandatory vaccination policies but contend that the notion of "mandatory" differs from that of other nations.

Vaccines that are not mandatory are not publicly funded, so the cost for those must be borne by parents or employers, she adds. Funded vaccinations include tuberculosis, diphtheria, measles, hepatitis B, human papilloma virus for 12-year-old girls, and tick-borne encephalitis until age 18 in endemic areas and for orphans.

Latvia also appears unique in that it compels health care providers to obtain the signatures of those who decline vaccination. Individuals have the right to refuse a vaccination, but if they do so, health providers have a duty to explain the health consequences.

United Kingdom

Health experts have criticized media reporting of the MMR-autism controversy for triggering a decline in vaccination rates and a rise in the incidence of these diseases.[40] Before publication of Wakefield's findings, the inoculation rate for MMR in the UK was 92%; after publication, the rate dropped to below 80%. In 1998, there were 56 measles cases in the UK; by 2008, there were 1348 cases, with two confirmed deaths.[41]

United States

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices makes scientific recommendations which are generally followed by the federal government, state governments, and private health insurance companies.

States in the U.S. mandate immunization, or obtaining exemption, before children enroll in public school. Exemptions are typically for people who have compromised immune systems, allergies to the components used in vaccinations, or strongly held objections. All states but California, West Virginia, and Mississippi allow religious exemptions, and fifteen states allow parents to cite personal, conscientious or philosophical objections.[43] A widespread and growing number of parents claim religious and philosophical beliefs to get vaccination exemptions: researchers have cited these exemptions as contributing to loss of herd immunity within these communities, and hence an increasing number of disease outbreaks.[44]

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) notes the dilemma faced by many parents in that vaccines are a very safe and important health intervention, but are neither risk-free nor 100% effective. It advises physicians to respect the refusal of parents to vaccinate their child after adequate discussion, unless the child is put at significant risk of harm (e.g., during an epidemic, or after a deep and contaminated puncture wound). Under such circumstances, the AAP states that parental refusal of immunization constitutes a form of medical neglect and should be reported to state child protective services agencies.[45]

See Vaccination schedule for the vaccination schedule used in the United States.

Immunizations are often compulsory for military enlistment in the U.S.[46]

All vaccines recommended by the U.S. government for its citizens are required for green card applicants.[47] This requirement has stirred controversy when it applied to the HPV vaccine because of the cost of the vaccine, and because the other thirteen required vaccines prevent diseases which are spread by a respiratory route and are considered highly contagious.[48] Persons opposed to vaccinations in any form, can file a waiver request showing that their objection is based on religious beliefs or moral convictions, and that these beliefs are sincere.[49]

In schools

In the United States, school vaccination laws have played an instrumental role in the control of vaccine-preventable diseases. The first mandatory school vaccination requirement was enacted in the 1850s in Massachusetts to prevent the spread of smallpox.[50] The mandatory school vaccination requirement was decided after the implementation of the compulsory school attendance law. Mainly because it caused a rapid growth in children in public schools which would facilitate the spread of smallpox. The early movement towards school vaccination laws began in the local level as they included counties, cities, and boards of education. By 1827, Boston had become the first city to mandate all children entering public schools to demonstrate evidence of vaccinations.[50] In addition, in 1855 the Commonwealth of Massachusetts had established their own statewide mandatory vaccination requirements for all students entering school. It would influence other states to implement similar statewide vaccination laws in schools as seen in New York in 1862, Pennsylvania in 1895, and Connecticut in 1872 and later to the Midwest, South and West of the US. By 1963, 20 states had school vaccination laws.[50]

Yet, these school vaccination laws were not easily accepted by many and caused political debates throughout the United States. An example of this political turmoil and resistance was evident in Chicago in 1893 where less than 10 percent of the children were vaccinated regardless of the twelve year old state law.[50] Resistance was seen in the local level of the school district as some local boards and superintendents opposed the state vaccination laws which led to the enforcement of state board health inspectors to examine vaccination polices in schools. Resistance proceeded even during the mid-1900s and in 1977 a nationwide Childhood Immunization Initiative was developed to increase vaccination levels in children to 90% by 1979.[51] During the two-year period of observation, the initiative reviewed the immunization records of more than 28 million children and vaccinated children that needed to be vaccinated.

In 1922 the constitutionality of childhood vaccination was examined in the Supreme Court case Zucht v. King. The court decided that a school could deny admission to children who failed to provide a certification of vaccination for the protection of the public health.[51] In 1987, a measles epidemic occurred in Maricopa County, Arizona and another court case, Maricopa County Health Department vs. Harmon, examined the arguments of an individual's right to education over the states need to protect against the spread of disease. The court decided that it is prudent to take action to combat the spread of disease by denying un-vaccinated children a place in school until the risk for the spread of measles was confirmed.[51]

Currently, in a push to eradicate pertussis, tetanus, diphtheria, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, and hepatitis B from the population, schools across the United States require an updated immunization record for all incoming and returning students. While all states require an immunization record, this does not mean that all students must get vaccinated. Opt-out criteria is determined at a state level. In the United States, opt-outs take one of three forms: medical, in which a vaccine is contraindicated due to a component ingredient allergy or existing medical condition; religious; and personal philosophical opposition. As of 2015, 47 states allow religious exemptions, with some states requiring proof of religious membership. Mississippi, West Virginia and California do not permit religious exemptions.[52] Only 15 states allow personal philosophical opposition to vaccination as a form of exemption; Vermont and California eliminated this exemption in 2015.[43][52]

France

In France, the High Council of Public Health is in charge of proposing vaccine recommendations to the Minister of Health. Each year, immunization recommendations for both the general population and specific groups are published by the Institute of Epidemiology and Surveillance.[france 1] Since some hospitals are granted additional freedoms, there two key people responsible for vaccine policy within hospitals: the Operational physician (OP), and the Head of the hospital infection and prevention committee (HIPC).[france 1] Mandatory immunization policies on BCG, diphtheria, tetanus, and poliomyelitis began in the 1950s and policies on Hepatitis B began in 1991. Recommended but not mandatory suggestions on influenza, pertussis, varicella, and measles began in 2000, 2004, 2004, and 2005, respectively.[france 1] According to the 2013 INPES Peretti-Watel health barometer, between 2005 and 2010, the percentage of French people between 18–75 years old in favor of vaccination dropped from 90% to 60%. Conversely, those who claimed to be anti-vaccination increased from 8.5% in 2005 to 38.2% in 2010.[54] Since 2009, France has recommended meningococcus C vaccination for infants 1–2 years old, with a catch up dosage up to 25 years later. French insurance companies have reimbursed this vaccine since January 2010, at which point coverage levels were 32.3% for children 1–2 years and 21.3% for teenagers 14–16 years old.[55] In 2012, the French government and the Institut de veille sanitaire launched a 5-year national program in order to improve vaccination policy. The program simplified guidelines, facilitated access to vaccination, and invested in vaccine research.[56] In 2014, fueled by rare health-related scandals, mistrust of vaccines became a common topic in the French public debate on health.[57] According to a French radio station, as of 2014, 3 to 5 percent of kids in France were not given the mandatory vaccines.[57] Some families may avoid requirements by finding a doctor willing to forge a vaccination certificate, a solution which numerous French forums confirm. However, the French State considers "vaccine refusal" a form of child abuse.[57] In some instances, parental vaccine refusals may result in criminal trials. France's 2010 creation of the Question Prioritaire Constitutionelle (QPC) allows lower courts to refer constitutional questions to the highest court in the relevant hierarchy.[france 2] Therefore, criminal trials based on vaccine refusals may be referred to the Cour de Cassation, which will then certify whether the case meets certain criteria.[france 2] In May 2015, France updated its vaccination policies on diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, polio, Haemophilus influenzae b infections, and hepatitis B for premature infants.[58] As of 2015, while failure to vaccinate is not necessarily illegal, a parent's right to refuse to vaccinate his or her child is technically a constitutional matter. Additionally, children in France cannot enter schools without proof of vaccination against diphtheria, tetanus, and polio.[59] French Health Minister, Marisol Touraine, finds vaccinations "absolutely fundamental to avoid disease," and has pushed to have both trained pharmacists and doctors administer vaccinations.[59] Most recently, the Prime Minister's 2015-2017 roadmap for the "multi-annual social inclusion and anti-poverty plan" includes free vaccinations in certain public facilities.[60] Vaccinations within the immunization schedule are given for free at immunization services within the public sector. When given in private medical practices, vaccinations are 65% reimbursed.[61]

Italy

As aging populations in Italy bring a rising burden of age-related disease, the Italian vaccination system remains complex.[62] The fact that services and decisions are delivered by 21 separate regional authorities creates many variations in Italian vaccine policy.[62] There is a National committee on immunizations that updates the national recommended immunization schedule, with input from the ministry of health representatives, regional health authorities, national institute of health, and other scientific societies.[63] Regions may add more scheduled vaccinations, but cannot exempt citizens from nationally mandated or recommended ones.[63] For instance, a nationwide plan for eliminating measles and rubella began in 2001.[63] Certain vaccinations in Italy are based on findings from the National Centre for Epidemiology, Surveillance and Health Promotion are also used to determine miscellaneous vaccination mandates.[64] Childhood vaccinations included in national schedules are guaranteed free of charge for all Italian children and foreign children who live in the country.[63] Estimated insurance coverage for the required three doses of HBV-Hib-IPV vaccines is at least 95% when the child is 2 years old. Later, Influenza is the only nationally necessary vaccine for adults, and is administered by general practitioners.[63] To mitigate some public concerns, Italy currently has a national vaccine injury compensation program. Essentially, those who are ill or damaged by mandatory and recommended vaccinations may receive funding from the government as compensation.[65] One evaluation of vaccine coverage in 2010, which covered the 2008 birth cohort, showed a slight decline in immunization insurance coverage rates of diphtheria, hepatitis B, polio, and tetanus after those specific vaccinations had been made mandatory.[66] However, vaccination levels continued to pass the Italian government's goal of 95% outreach.[66] Aiming to integrate immunization strategies across the country and equitize access to disease prevention, the Italian Ministry of Health issued the National Immunization Prevention Plan (Piano Nazionale Prevenzione Vaccinale) in 2012. This plan for 2012-2014 introduced an institutional "lifecourse" approach to vaccination to complement the Italian health policy agenda.[67] HPV vaccine coverage increased well, and pneumococcal vaccine and meningococcal C vaccines faced positive public reception. However, both infant vaccine coverage rates and influenza immunization in the elderly have been decreasing.[67] A 2015 government plan in Italy aimed to boost vaccination rates and introduce a series of new vaccines, triggering protests among public health professionals.[68] Partially in response to the statistic that less than 86% of Italian children receive the measles shot, the National Vaccination Plan for 2016–18 (PNPV) increased vaccination requirements.[68] For instance, nationwide varicella shots would be required for newborns.[68] Under this plan, government spending on vaccines would double to €620 million annually, and children may be barred from attending school without proving vaccination.[68] Although these implementations would make Italy a European frontrunner in vaccination, some experts question the need for several of the vaccines, and some physicians worry about the potential punishment they may face if they do not comply with the proposed regulations.[68]

Spain

Spain's 19 autonomous communities, consisting of 17 Regions and 2 cities, follow health policies established by the Inter-Territorial Health Council that was formed by the National and Regional Ministries of Health.[69] This Inter-Territorial Council is composed of representatives from each region and meets to discuss health related issues spanning across Spain. The Institute of Health Carlos III (ISCIIII) is a public research institute that manages biomedical research for the advancement of health sciences and disease preventions.[70] The ISCIII may suggest the introduction of new vaccines into Spain's Recommended Health Schedule and is under direct control of the Ministry of Health. Although the Ministry of Health is responsible for the oversight of health care services, the policy of devolution divides responsibilities among local agencies, including health planning and programing, fiscal duties, and direct management of health services. This decentralization proposes difficulties in collecting information at the national level.[71] The Inter-Territorial Council's Commission on Public Health works to establish health care policies according to recommendations by technical working groups via letters, meetings, and conferences. The Technical Working Group on Vaccines review data on vaccine preventable diseases and proposes recommendations for policies.[71] No additional groups outside the government propose recommendations. Recommendations must be approved by the Commission of Public Health and then by the Inter-Territorial Council, at which point they are incorporated into the National Immunization Schedule.[69]

The Spanish Association of Pediatrics, in conjunction with the Spanish Medicines Agency, outlines specifications for vaccination schedules and policies and provides a history of vaccination policies implemented in the past, as well as legislature pertaining to the public currently. Spain's Constitution does not mandate vaccination, so it is voluntary unless authorities require compulsory vaccination in the case of epidemics.[72] In 1921 vaccination became mandatory for smallpox, and in 1944 the Bases Health Act mandated compulsory vaccination for diphtheria and smallpox, but was suspended in 1979 after the elimination of the threat of an epidemic.[72] The first systematic immunization schedule for the provinces of Spain was established in 1975 and has continuously been updated by each autonomous community in regard to doses at certain ages and recommendation of additional vaccine not proposed in the schedule.[72] The 2015 schedule proposed the newest change with the inclusion of pneumococcal vaccine for children under 12 months. For 2016, the schedule plans to propose a vaccine against varicella in children at 12–15 months and 3–4 years. Furthermore, the General Health Law of 1986 echoes Article 40.2 from the Constitution guaranteeing the right to the protection of health, and states employers must provide vaccines to workers if they are at risk of exposure.[73] Due to vaccination coverage in each Community, there is little anti-vaccine activity or opposition to the current schedule, and no organized groups against vaccines.[69] The universal public health care provides coverage for all residents, while central and regional support programs extend coverage to immigrant populations. However, no national funds are granted to the Communities for vaccine purchases. Vaccines are financed from taxes, and paid in full by the Community government.[69] Law 21 in Article 2.6 establishes the need for proper clinical documentation and informed consent by the patient, although written informed consent is not mandated in the verbal request of a vaccine for a minor.[74] The autonomous regions collect data, from either electronic registries or written physician charts, to calculate immunization coverage.[69]

Germany

In Germany, the Standing Vaccination Committee (STIKO) is the federal commission responsible for recommending an immunization schedule. The Robert Kosh Institute in Berlin (RKI) compiles data of immunization status upon the entry of children at school, and measures vaccine coverage of Germany at a national level.[75] Founded in 1972, the STIKO is composed of 12-18 volunteers, appointed members by the Federal Ministry for Health for 3-year terms.[76] Members include experts from many scientific disciplines and public health fields and professionals with extensive experience on vaccination.[71] The independent advisory group meets biannually to address issues pertaining to preventable infectious diseases.[77] Although the STIKO makes recommendations, immunization in Germany is voluntary and there are no official government recommendations. German Federal States typically follow the Standing Vaccination Committee's recommendations minimally, although each state can make recommendations for their geographic jurisdiction that extends beyond the recommended list.[75] In addition to the proposed immunization schedule for children and adults, the STIKO recommends vaccinations for occupational groups, police, travelers, and other at risk groups.[75] Vaccinations recommendations that are issued must be in accordance with the Protection Against Infection Act (Infektionsschutzgesetz), which regulates the prevention of infectious diseases in humans.[78] If a vaccination is recommended because of occupational risks, it must adhere to the Occupational Safety and Health Act involving Biological Agents.[79] Criteria for the recommendation include disease burden, efficacy and effectiveness, safety, feasibility of program implementation, cost-effectiveness evaluation, clinical trial results, and equity in access to the vaccine.[71] In the event of vaccination related injuries, federal states are responsible for monetary compensation.[79] Germany's central government does not finance childhood immunizations, so 90% of vaccines are administered in a private physician's office and paid for through insurance. The other 10% of vaccines are provided by the states in public health clinics, schools, or day care centers by local immunization programs.[75] Physician responsibilities concerning immunization include beginning infancy vaccination, administering booster vaccinations, maintaining medical and vaccination history, and giving information and recommendations concerning vaccines.[79]

See also

References

- ↑ UNICEF (February 2014). Global Immunization Data (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ↑ Domestic Public Health Achievements Team (20 May 2011). "Ten Great Public Health Achievements - United States, 2001-2010". Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 60 (19): 619–23. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ "History of Public Health: 12 Great Achievements". Canadian Public Health Association. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ Fine PE, Clarkson JA (1986). "Individual versus public priorities in the determination of optimal vaccination policies". Am. J. Epidemiol. 124 (6): 1012–20. PMID 3096132.

- ↑ Bauch CT, Galvani AP, Earn DJ (2003). "Group interest versus self-interest in smallpox vaccination policy". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100 (18): 10564–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1731324100. PMC 193525

. PMID 12920181.

. PMID 12920181.

- ↑ Vardavas R, Breban R, Blower S (2007). "Can Influenza Epidemics Be Prevented by Voluntary Vaccination?". PLoS Comput. Biol. 3 (5): e85. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030085. PMC 1864996

. PMID 17480117.

. PMID 17480117.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (August 2014). "Parent's Guide to Childhood Immunizations" (PDF). Department of Health and Human Services. CS250472.

- 1 2 El Amin AN, Parra MT, Kim-Farley R, Fielding JE. "Ethical Issues Concerning Vaccination Requirements" (PDF). Public Health Rev. 34 (1): 1–20.

- ↑ Salmon DA, Teret SP, MacIntyre CR, Salisbury D, Burgess MA, Halsey NA (2006). "Compulsory vaccination and conscientious or philosophical exemptions: past, present, and future". Lancet. 367 (9508): 436–42. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68144-0. PMID 16458770.

- ↑ Meade T (1989). "'Living worse and costing more': resistance and riot in Rio de Janeiro, 1890–1917". J. Lat. Am. Stud. 21 (2): 241–66. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00014784.

- ↑ Wolfe R, Sharp L (2002). "Anti-vaccinationists past and present". BMJ. 325 (7361): 430–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7361.430. PMC 1123944

. PMID 12193361.

. PMID 12193361.

- ↑ Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR (2000). "Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults". Am. J. Prev. Med. 18 (1 Suppl): 97–140. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00118-X. PMID 10806982.

- ↑ Ndiaye SM, Hopkins DP, Shefer AM (2005). "Interventions to improve influenza, pneumococcal polysaccharide, and hepatitis B vaccination coverage among high-risk adults: a systematic review". Am. J. Prev. Med. 28 (5 Suppl): 248–79. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.02.016. PMID 15894160.

- 1 2 3 4 Ibuka, Yoko; Li, Meng; Vietri, Jeffrey; Chapman, Gretchen B.; Galvani, Alison P. (2014-01-01). "Free-riding behavior in vaccination decisions: an experimental study". PloS One. 9 (1): e87164. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087164. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3901764

. PMID 24475246.

. PMID 24475246. - ↑ Stiglitz, Joseph (2000). Economics of the Public Sector. Territory Rights Worldwide. ISBN 978-0-393-96651-0.

- ↑ Serpell, Lucy; Green, John (2006-05-08). "Parental decision-making in childhood vaccination". Vaccine. 24 (19): 4041–4046. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.02.037. ISSN 0264-410X. PMID 16530892.

- ↑ Francis, Peter J. (1997-02-01). "Dynamic epidemiology and the market for vaccinations". Journal of Public Economics. 63 (3): 383–406. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(96)01586-1.

- ↑ Deogaonkar, Rohan; Hutubessy, Raymond; van der Putten, Inge; Evers, Silvia; Jit, Mark (2012-10-16). "Systematic review of studies evaluating the broader economic impact of vaccination in low and middle income countries". BMC public health. 12: 878. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-878. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 3532196

. PMID 23072714.

. PMID 23072714. - ↑ Francis, Peter J. (2004-09-01). "Optimal tax/subsidy combinations for the flu season". Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. 28 (10): 2037–2054. doi:10.1016/j.jedc.2003.08.001.

- ↑ Oraby, Tamer; Thampi, Vivek; Bauch, Chris T. (2014-04-07). "The influence of social norms on the dynamics of vaccinating behaviour for paediatric infectious diseases". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 281 (1780): 20133172. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.3172. ISSN 1471-2954. PMC 4078885

. PMID 24523276.

. PMID 24523276. - ↑ Meszaros, Jacqueline R.; Asch, David A.; Baron, Jonathan; Hershey, John C.; Kunreuther, Howard; Schwartz-Buzaglo, Joanne. "Cognitive processes and the decisions of some parents to forego pertussis vaccination for their children". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 49 (6): 697–703. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(96)00007-8.

- ↑ Zhou, Fangjun; Santoli, Jeanne; Messonnier, Mark L.; Yusuf, Hussain R.; Shefer, Abigail; Chu, Susan Y.; Rodewald, Lance; Harpaz, Rafael (2005-12-01). "Economic Evaluation of the 7-Vaccine Routine Childhood Immunization Schedule in the United States, 2001". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 159 (12). doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1136. ISSN 1072-4710.

- 1 2 3 4 Zhou, Fangjun; Shefer, Abigail; Wenger, Jay; Messonnier, Mark; Wang, Li Yan; Lopez, Adriana; Moore, Matthew; Murphy, Trudy V.; Cortese, Margaret (2014-04-01). "Economic evaluation of the routine childhood immunization program in the United States, 2009". Pediatrics. 133 (4): 577–585. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0698. ISSN 1098-4275. PMID 24590750.

- ↑ Gargano, Lisa M.; Tate, Jacqueline E.; Parashar, Umesh D.; Omer, Saad B.; Cookson, Susan T. (2015-01-01). "Comparison of impact and cost-effectiveness of rotavirus supplementary and routine immunization in a complex humanitarian emergency, Somali case study". Conflict and Health. 9: 5. doi:10.1186/s13031-015-0032-y. PMC 4331177

. PMID 25691915.

. PMID 25691915. - ↑ van Hoek, Albert Jan; Campbell, Helen; Amirthalingam, Gayatri; Andrews, Nick; Miller, Elizabeth. "Cost-effectiveness and programmatic benefits of maternal vaccination against pertussis in England". Journal of Infection. 73 (1): 28–37. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2016.04.012.

- ↑ Diop, Abdou; Atherly, Deborah; Faye, Alioune; Sall, Farba Lamine; Clark, Andrew D.; Nadiel, Leon; Yade, Binetou; Ndiaye, Mamadou; Cissé, Moussa Fafa. "Estimated impact and cost-effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination in Senegal: A country-led analysis". Vaccine. 33: A119–A125. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.12.065.

- ↑ Ehreth, Jenifer (2003-01-30). "The global value of vaccination". Vaccine. Vaccines and Immunisation 2003. Based on the Third World Congress on Vaccines and Immunisation. 21 (7–8): 596–600. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00623-0.

- ↑ "Global Immunization Vision and Strategy". Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. World Health Organization. 1 December 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ "Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011 - 2020". Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. World Health Organization. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ Peatling, Stephanie (13 April 2015). "Support for government push to withdraw welfare payments from anti vaccination parents". Federal Politics. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ↑ "About the Program". Immunise Australia Program. Australian Government, Department of Health. 4 September 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ "Free vaccine Victoria — Criteria for eligibility". Health. State Government of Victoria. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ "Your child's immunisation schedule". Australian Childhood Immunisation Register for health professionals. Australian Government Department of Human Services. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ "Immunisations for children and young people". Citizens Information. Citizens Information Board, Republic of Ireland. 16 September 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ Dr Sigrun Roesel; Dr Kaushik Banerjee. School Immunization Programme in Malaysia—24 February to 4 March 2008 (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization.

- 1 2 Walkinshaw E (11 October 2011). "Mandatory vaccinations: The international landscape". Can. Med. Assoc. J. 183 (16). doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-3993. PMID 21989473.

- ↑ Mrvic T, Petrovec M, Breskvar M, Zupanc TL, Logar M (31 March 2012). Mandatory measles vaccination – are healthcare workers really safe?. 22nd European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. London. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ Irena Grmek Kosnik (2012). "Success of the vaccination campaign in Slovenia" (PDF of slidedeck). International Scientific Working Group on Tick-Borne Encephalitis.

- ↑

- ↑ "Doctors issue plea over MMR jab". BBC News. 2006-06-26. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ↑ Thomas J. Paranoia strikes deep: MMR vaccine and autism. Psychiatric Times. 2010;27(3):1-6

- ↑ "Immunization Schedules". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- 1 2 "States with Religious and Philosophical Exemptions from School Immunization Requirements". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ Ciolli A (2008). "Mandatory School Vaccinations: The Role of Tort Law". Yale J Biol Med. 81 (3): 129–37. PMC 2553651

. PMID 18827888.

. PMID 18827888. - ↑ Diekema DS, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics (2005). "Responding to parental refusals of immunization of children". Pediatrics. 115 (5): 1428–31. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0316. PMID 15867060.

- ↑ United States Department of Defense. "MilVax homepage". Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ↑ "Report of Medical Examination and Vaccination Record". USCIS.

- ↑ Jordan M (2008-10-01). "Gardasil requirement for immigrants stirs backlash". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ↑ "Waivers of Health-Based Inadmissibility for U.S. Green Card Applicants". nolo.com. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Hodge, Jr; James G and Gostin; Lawrence O (2001). "School Vaccination Requirements: Historical, Social, and Legal Perspectives". Ky. LJ. 90: 8331.

- 1 2 3 Malone, Kevin M; Hinman, Alan R (2003). "The Public Health Imperative and Individual Rights". Law in Public Health Practice. Oxford University Press: 262–284.

- 1 2 Horowitz, Julia (30 June 2015). "California governor signs strict school vaccine legislation". Associated Press. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Vaccine Schedule Quick Search". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Network. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ Cáceres, Marco. "The French National Debate on Vaccine Safety.". The Vaccine Reaction. National Vaccine Information Center.

- ↑ Stahl, JP, R. Cohen, Denis, Gaudelus, Lery, Lepetit, Martinot (2013-02-18). "Vaccination against meningococcus C. vaccinal coverage in the French target population.". National Center for Biotechnology Information. 43 (2): 75–80. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2013.01.001. PMID 23428390.

- ↑ Loulergue, Floret, Launay (2015-04-25). "Strategies for decision-making on vaccine use: the French experience". National Center for Biotechnology Information. 14 (7): 917–922. doi:10.1586/14760584.2015.1035650.

- 1 2 3 Rouillon, Etienne. "Charges Against French Parents Stir Mandatory Vaccination Debate". VICE NEWS. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- ↑ "Avis Et Rapports Du HCSP.". HCSP. Haut Conseil De La Sante Publique.

- 1 2 Greenhouse, Emily. "How France Is Handling Its Own Vaccine Debate". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg.

- ↑ ""The Fight against Poverty: "The Challenge Is to Preserve Our Social Model and Its Underlying Values""". Gouvernement.fr. General Assembly on Social Work.

- ↑ "Prevention En Sante.". Ministere De Affaires Sociales Et De La Sante. French Government.

- 1 2 Webicine Journalists. "Italy Embraces 'life-course Immunisation". Vaccines Today. EFPIA. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Ministero Della Salute". Italian Ministry of Health. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- ↑ Elena, Regina. "In Evidenza.". Il Portale Dell'epidemiologia per La Sanità Pubblica. Epicentro.

- ↑ Holland, Mary. "U.S. Media Blackout: Italian Courts Rule Vaccines Cause Autism.". Global Research. Centre for Research on Globalization.

- 1 2 Haverkate, D’Ancona, Giambi, Johansen, Lopalco, Cozza, and Appelgren. "Mandatory And Recommended Vaccination In The EU, Iceland And Norway: Results Of The Venice 2010 Survey On The Ways Of Implementing National Vaccination Programmes.". Eurosurveillance. Retrieved 10 Mar 2016.

- 1 2 Bonanni, Ferro, Guerra, Iannazzo, Odone, Pompa, Rizzuto, Signorelli (July 2013). "Vaccine Coverage in Italy and Assessment of the 2012-2014 National Immunization Prevention Plan". National Center for Biotechnology Information. 39 (4): 146–158. PMID 26499433.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Margottini, Laura. "New Vaccination Strategy Stirs Controversy in Italy.". Science Insider. AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Delgado, Sinesio. "Spain" (PDF). Instituto De Salud Carlos III. Centro Nacional De Epidemiologia. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ↑ "Functions". Instituto De Salud Carlos III. Gobierno de España, Minesterio de Economia y Copmetitividad. Retrieved March 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Ricciardi, G.W.; Toumi, M.; Weil-Oliver, C.; Reutekinberg, E.J.; Dano, D.; Duru, G.; Picazo, J; Zollner, Y.; Poland, G.; Drummond, M. (September 2014). "Comparisons of NITAG Policies and Working Processes in Selected Developed Countries". Elsevier.

- 1 2 3 "Voluntary- Mandatory, Consent, and Waiver Vaccination". Vaccination ASP. Asociacíon Españada de Pediatría, Comité Asesor de Vacunas. Retrieved March 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Occupational Health Regulations". Ministry of Health, Social Services, and Equality. Ministry of Health. Retrieved March 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Immunisation Schedules in Spain". Vaccination ASP. Asociacíon Españada De Pediatría, Comité Asesor De Vacunas. Retrieved March 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 "Germany" (PDF). Vaccination European New Integrated Collaboration Effort. Venice III.

- ↑ "The German Standing Committee of Vaccination". Robert Kosh Institut.

- ↑ "Vaccinations". G-BA. Bermeinsamer Bundesausschuss. Retrieved March 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Kerwat, K.M.; Just, M.; Wulf, H. (March 2009). "The German Protection Against INfection Act (Infektionsschutzgesetz (IfSG)". Unbound Medicine.

- 1 2 3 "Recommendations of the Standing Committee on Vaccinations STIKO at the Robert Kosh Institute" (PDF). Epidemiologisches Bulletin. Robert Kosh Institute. Retrieved March 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)