Convex hull

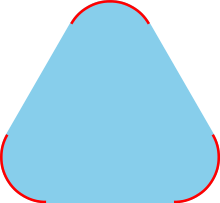

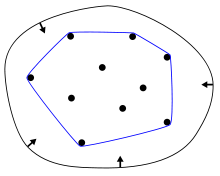

In mathematics, the convex hull or convex envelope of a set X of points in the Euclidean plane or in a Euclidean space (or, more generally, in an affine space over the reals) is the smallest convex set that contains X. For instance, when X is a bounded subset of the plane, the convex hull may be visualized as the shape enclosed by a rubber band stretched around X.[1]

Formally, the convex hull may be defined as the intersection of all convex sets containing X or as the set of all convex combinations of points in X. With the latter definition, convex hulls may be extended from Euclidean spaces to arbitrary real vector spaces; they may also be generalized further, to oriented matroids.[2]

The algorithmic problem of finding the convex hull of a finite set of points in the plane or other low-dimensional Euclidean spaces is one of the fundamental problems of computational geometry.

Definitions

A set of points is defined to be convex if it contains the line segments connecting each pair of its points. The convex hull of a given set X may be defined as

- The (unique) minimal convex set containing X

- The intersection of all convex sets containing X

- The set of all convex combinations of points in X.

- The union of all simplices with vertices in X.

It is not obvious that the first definition makes sense: why should there exist a unique minimal convex set containing X, for every X? However, the second definition, the intersection of all convex sets containing X is well-defined, and it is a subset of every other convex set Y that contains X, because Y is included among the sets being intersected. Thus, it is exactly the unique minimal convex set containing X. Each convex set containing X must (by the assumption that it is convex) contain all convex combinations of points in X, so the set of all convex combinations is contained in the intersection of all convex sets containing X. Conversely, the set of all convex combinations is itself a convex set containing X, so it also contains the intersection of all convex sets containing X, and therefore the sets given by these two definitions must be equal. In fact, according to Carathéodory's theorem, if X is a subset of an N-dimensional vector space, convex combinations of at most N + 1 points are sufficient in the definition above. Therefore, the convex hull of a set X of three or more points in the plane is the union of all the triangles determined by triples of points from X, and more generally in N-dimensional space the convex hull is the union of the simplices determined by at most N + 1 vertices from X.

If the convex hull of X is a closed set (as happens, for instance, if X is a finite set or more generally a compact set), then it is the intersection of all closed half-spaces containing X. The hyperplane separation theorem proves that in this case, each point not in the convex hull can be separated from the convex hull by a half-space. However, there exist convex sets, and convex hulls of sets, that cannot be represented in this way. Open halfspaces are such examples.

More abstractly, the convex-hull operator Conv() has the characteristic properties of a closure operator:

- It is extensive, meaning that the convex hull of every set X is a superset of X.

- It is non-decreasing, meaning that, for every two sets X and Y with X ⊆ Y, the convex hull of X is a subset of the convex hull of Y.

- It is idempotent, meaning that for every X, the convex hull of the convex hull of X is the same as the convex hull of X.

Convex hull of a finite point set

The convex hull of a finite point set is the set of all convex combinations of its points. In a convex combination, each point in is assigned a weight or coefficient in such a way that the coefficients are all non-negative and sum to one, and these weights are used to compute a weighted average of the points. For each choice of coefficients, the resulting convex combination is a point in the convex hull, and the whole convex hull can be formed by choosing coefficients in all possible ways. Expressing this as a single formula, the convex hull is the set:

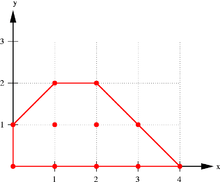

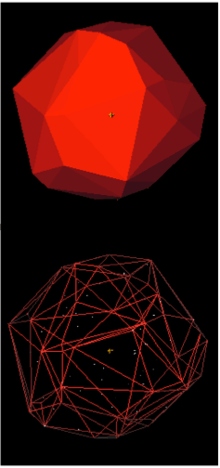

The convex hull of a finite point set forms a convex polygon when n = 2, or more generally a convex polytope in . Each point in that is not in the convex hull of the other points (that is, such that ) is called a vertex of . In fact, every convex polytope in is the convex hull of its vertices.

If the points of are all on a line, the convex hull is the line segment joining the outermost two points. When the set is a nonempty finite subset of the plane (that is, two-dimensional), we may imagine stretching a rubber band so that it surrounds the entire set and then releasing it, allowing it to contract; when it becomes taut, it encloses the convex hull of .[1]

In two dimensions, the convex hull is sometimes partitioned into two polygonal chains, the upper hull and the lower hull, stretching between the leftmost and rightmost points of the hull. More generally, for points in any dimension in general position, each facet of the convex hull is either oriented upwards (separating the hull from points directly above it) or downwards; the union of the upward-facing facets forms a topological disk, the upper hull, and similarly the union of the downward-facing facets forms the lower hull.[3]

Computation of convex hulls

In computational geometry, a number of algorithms are known for computing the convex hull for a finite set of points and for other geometric objects.

Computing the convex hull means constructing an unambiguous, efficient representation of the required convex shape. The complexity of the corresponding algorithms is usually estimated in terms of n, the number of input points, and h, the number of points on the convex hull.

For points in two and three dimensions, output-sensitive algorithms are known that compute the convex hull in time O(n log h). For dimensions d higher than 3, the time for computing the convex hull is , matching the worst-case output complexity of the problem.[4]

Minkowski addition and convex hulls

![Three squares are shown in the nonnegative quadrant of the Cartesian plane. The square Q1=[0,1]×[0,1] is green. The square Q2=[1,2]×[1,2] is brown, and it sits inside the turquoise square Q1+Q2=[1,3]×[1,3].](../I/m/Minkowski_sum.png)

The operation of taking convex hulls behaves well with respect to the Minkowski addition of sets.

- In a real vector-space, the Minkowski sum of two (non-empty) sets S1 and S2 is defined to be the set S1 + S2 formed by the addition of vectors element-wise from the summand-sets

- S1 + S2 = { x1 + x2 : x1 ∈ S1 and x2 ∈ S2 }.

More generally, the Minkowski sum of a finite family of (non-empty) sets Sn is the set formed by element-wise addition of vectors

- ∑ Sn = { ∑ xn : xn ∈ Sn }.

- For all subsets S1 and S2 of a real vector-space, the convex hull of their Minkowski sum is the Minkowski sum of their convex hulls

- Conv( S1 + S2 ) = Conv( S1 ) + Conv( S2 ).

This result holds more generally for each finite collection of non-empty sets

- Conv( ∑ Sn ) = ∑ Conv( Sn ).

In other words, the operations of Minkowski summation and of forming convex hulls are commuting operations.[5][6]

These results show that Minkowski addition differs from the union operation of set theory; indeed, the union of two convex sets need not be convex: The inclusion Conv(S) ∪ Conv(T) ⊆ Conv(S ∪ T) is generally strict. The convex-hull operation is needed for the set of convex sets to form a lattice, in which the "join" operation is the convex hull of the union of two convex sets

- Conv(S)∨Conv(T) = Conv( S ∪ T ) = Conv( Conv(S) ∪ Conv(T) ).

Relations to other structures

The Delaunay triangulation of a point set and its dual, the Voronoi diagram, are mathematically related to convex hulls: the Delaunay triangulation of a point set in Rn can be viewed as the projection of a convex hull in Rn+1.[7]

Topologically, the convex hull of an open set is always itself open, and the convex hull of a compact set is always itself compact; however, there exist closed sets for which the convex hull is not closed.[8] For instance, the closed set

has the open upper half-plane as its convex hull.

Applications

The problem of finding convex hulls finds its practical applications in pattern recognition, image processing, statistics, geographic information system, game theory, construction of phase diagrams, and static code analysis by abstract interpretation. It also serves as a tool, a building block for a number of other computational-geometric algorithms such as the rotating calipers method for computing the width and diameter of a point set.

The convex hull is commonly known as the minimum convex polygon (MCP) in ethology, where it is a classic, though perhaps simplistic, approach in estimating an animal's home range based on points where the animal has been observed.[9] Outliers can make the MCP excessively large, which has motivated relaxed approaches that contain only a subset of the observations (e.g., find an MCP that contains at least 95% of the points).[10]

See also

- Affine hull

- Alpha shape

- Choquet theory

- Concave set

- Helly's theorem

- Holomorphically convex hull

- Krein–Milman theorem

- Linear hull

- Oloid

- Orthogonal convex hull

Notes

- 1 2 de Berg et al. (2000), p. 3.

- ↑ Knuth (1992).

- ↑ de Berg et al. (2000), p. 6. The idea of partitioning the hull into two chains comes from an efficient variant of Graham scan by Andrew (1979).

- ↑ Chazelle (1993).

- ↑ Krein & Šmulian (1940), Theorem 3, pages 562–563.

- ↑ For the commutativity of Minkowski addition and convexification, see Theorem 1.1.2 (pages 2–3) in Schneider (1993); this reference discusses much of the literature on the convex hulls of Minkowski sumsets in its "Chapter 3 Minkowski addition" (pages 126–196).

- ↑ Brown (1979).

- ↑ Grünbaum (2003), p. 16.

- ↑ Kernohan, Gitzen & Millspaugh (2001), p. 137–140

- ↑ Examples: The v.adehabitat.mcp GRASS module and adehabitatHR R package with percentage parameters for MCP calculation.

References

- Andrew, A. M. (1979), "Another efficient algorithm for convex hulls in two dimensions", Information Processing Letters, 9 (5): 216–219, doi:10.1016/0020-0190(79)90072-3.

- Brown, K. Q. (1979), "Voronoi diagrams from convex hulls", Information Processing Letters, 9 (5): 223–228, doi:10.1016/0020-0190(79)90074-7.

- de Berg, M.; van Kreveld, M.; Overmars, Mark; Schwarzkopf, O. (2000), Computational Geometry: Algorithms and Applications, Springer, pp. 2–8.

- Chazelle, Bernard (1993), "An optimal convex hull algorithm in any fixed dimension" (PDF), Discrete and Computational Geometry, 10 (1): 377–409, doi:10.1007/BF02573985.

- Grünbaum, Branko (2003), Convex Polytopes, Graduate Texts in Mathematics (2nd ed.), Springer, ISBN 9780387004242.

- Kernohan, Brian J.; Gitzen, Robert A.; Millspaugh, Joshua J. (2001), Joshua Millspaugh, John M. Marzluff, eds., "Ch. 5: Analysis of Animal Space Use and Movements", Radio Tracking and Animal Populations, Academic Press, ISBN 9780080540221.

- Knuth, Donald E. (1992), Axioms and hulls, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 606, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, p. ix+109, doi:10.1007/3-540-55611-7, ISBN 3-540-55611-7, MR 1226891.

- Krein, M.; Šmulian, V. (1940), "On regularly convex sets in the space conjugate to a Banach space", Annals of Mathematics, 2nd ser., 41: 556–583, doi:10.2307/1968735, JSTOR 1968735, MR 2009.

- Schneider, Rolf (1993), Convex bodies: The Brunn–Minkowski theory, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, 44, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-35220-7, MR 1216521.

External links

| The Wikibook Algorithm Implementation has a page on the topic of: Convex hull |