Critical reputation of Arthur Sullivan

The critical reputation of the British composer Arthur Sullivan has fluctuated markedly in the 150 years since he came to prominence. At first, critics regarded him as a potentially great composer of serious masterpieces. When Sullivan made a series of popular successes in comic operas with the librettist W.S. Gilbert, Victorian critics generally praised the operettas but reproached Sullivan for not writing solemn choral works instead. Immediately after Sullivan's death, his reputation was attacked by critics who condemned him for not taking part in what they conceived of as an "English musical renaissance". By the latter part of the 20th century, Sullivan's music was being critically reassessed, beginning with the first book devoted to a study of his music, The Music of Arthur Sullivan by Gervase Hughes (1960).

Early career

When the young Arthur Sullivan returned to England after his studies in Leipzig, critics were struck by his potential as a composer. His incidental music to The Tempest received an acclaimed premiere at the Crystal Palace on 5 April 1862. The Athenaeum wrote:

It was one of those events which mark an epoch in a man's life; and, what is of more universal consequence, it may mark an epoch in English music, or we shall be greatly disappointed. Years on years have elapsed since we have heard a work by so young an artist so full of promise, so full of fancy, showing so much conscientiousness, so much skill, and so few references to any model elect.[1]

His Irish Symphony of 1866 won similarly enthusiastic praise:

The symphony...is not only by far the most noticeable composition that has proceeded from Mr. Sullivan's pen, but the best musical work, if judged only by the largeness of its form and the number of beautiful thoughts it contains, for a long time produced by any English composer....[2]

But as Arthur Jacobs notes, "The first rapturous outburst of enthusiasm for Sullivan as an orchestral composer did not last." A comment that may be taken as typical of those that would follow the composer throughout his career was that "Sullivan's unquestionable talent should make him doubly careful not to mistake popular applause for artistic appreciation."[3]

Sullivan was also occasionally cited for a lack of diligence. For instance, of his early oratorio, The Prodigal Son, his teacher, John Goss, wrote:

All you have done is most masterly – Your orchestration superb, & your effects many of them original & first-rate.... Some day, you will, I hope, try another oratorio, putting out all your strength, but not the strength of a few weeks or months, whatever your immediate friends may say... only don't do anything so pretentious as an oratorio or even a Symphony without all your power, which seldom comes in one fit.[4]

Transition to opera

By the mid-1870s, Sullivan had turned his attention mainly to works for the theatre, for which he was generally admired. For instance, after the first performance of Trial by Jury (1875), the Times said that "It seems, as in the great Wagnerian operas, as though poem and music had proceeded simultaneously from one and the same brain."[5] But by the time The Sorcerer appeared, there were charges that Sullivan was wasting his talents in comic opera:

There is nothing whatever in Mr. Sullivan's score which any theatrical conductor engaged at a few pounds a week could not have written equally well.... We trust Mr. Sullivan is more proud of it than we can pretend to be. But we must confess to a sense of disappointment at the downward art course Mr. Sullivan appears to be now drifting into.... [He] has all the ability to make him a great composer, but he wilfully throws his opportunity away. A giant may play at times, but Mr. Sullivan is always playing.... He possesses all the natural ability to have given us an English opera, and, instead, he affords us a little more-or-less excellent fooling.[6]

Implicit in these comments was the view that comic opera, no matter how carefully crafted, was an intrinsically lower form of art. The Athenaeum's review of The Martyr of Antioch expressed a similar complaint:

It might be wished that in some portions Mr Sullivan had taken a loftier view of his theme, but at any rate he has written some most charming music, and orchestration equal, if not superior, to any that has ever proceeded from the pen of an English musician. And, further, it is an advantage to have the composer of H.M.S. Pinafore occupying himself with a worthier form of art.[7]

The operas with Gilbert themselves, however, garnered Sullivan high praise from the theatre reviewers. For instance, The Daily Telegraph wrote, "The composer has risen to his opportunity, and we are disposed to account Iolanthe his best effort in all the Gilbertian series."[8] Similarly, the Theatre would say that "the music of Iolanthe is Dr Sullivan's chef d'oeuvre. The quality throughout is more even, and maintained at a higher standard, than in any of his earlier works.... In every respect Iolanthe sustains Dr Sullivan's reputation as the most spontaneous, fertile, and scholarly composer of comic opera this country has ever produced."[9]

Knighthood and maturity

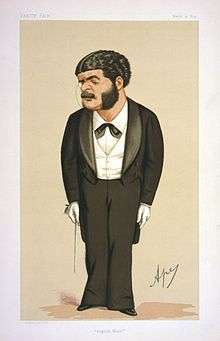

|

| Cartoon from Punch in 1880. It was premature in declaring Sullivan's knighthood, but was accompanied by a parody version of "When I, good friends" from Trial by Jury that summarised Sullivan's career to that date: |

| "A HUMOROUS KNIGHT." |

| ["It is reported that after the Leeds Festival Dr. Sullivan will be knighted." Having read this in a column of gossip, a be-nighted Contributor, who has "the Judge's Song" on the brain, suggests the following verse, adapted to probabilities.] |

|

After Sullivan was knighted in 1883, serious music critics renewed the charge that the composer was squandering his talent. The Musical Review of that year wrote:

Some things that Mr Arthur Sullivan may do, Sir Arthur ought not to do. In other words, it will look rather more than odd to see announced in the papers that a new comic opera is in preparation, the book by Mr W. S. Gilbert and the music by Sir Arthur Sullivan. A musical knight can hardly write shop ballads either; he must not dare to soil his hands with anything less than an anthem or a madrigal; oratorio, in which he has so conspicuously shone, and symphony, must now be his line. Here is not only an opportunity, but a positive obligation for him to return to the sphere from which he has too long descended.[10]

In Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Sir George Grove, who was an old friend of Sullivan's, recognised the artistry in the Savoy Operas while urging the composer to bigger and better things: "Surely the time has come when so able and experienced a master of voice, orchestra, and stage effect—master, too, of so much genuine sentiment—may apply his gifts to a serious opera on some subject of abiding human or natural interest."[10]

The premiere of The Golden Legend at the Leeds Festival in 1886 finally brought Sullivan the acclaim for a serious work that he had previously lacked. For instance, the critic of the Daily Telegraph wrote that "a greater, more legitimate and more undoubted triumph than that of the new cantata has not been achieved within my experience."[11] Similarly, Louis Engel in The World wrote that it was: "one of the greatest creations we have had for many years. Original, bold, inspired, grand in conception, in execution, in treatment, it is a composition which will make an "epoch" and which will carry the name of its composer higher on the wings of fame and glory. The effect it produced at rehearsal was enormous. The effect of the public performance was unprecedented."[12]

Hopes for a new departure were evident in the Daily Telegraph's review of The Yeomen of the Guard, Sullivan's most serious opera to that point:

The accompaniments... are delightful to hear, and especially does the treatment of the woodwind compel admiring attention. Schubert himself could hardly have handled those instruments more deftly, written for them more lovingly.... We place the songs and choruses in The Yeomen of the Guard before all his previous efforts of this particular kind. Thus the music follows the book to a higher plane, and we have a genuine English opera, forerunner of many others, let us hope, and possibly significant of an advance towards a national lyric stage.[13]

1890s

The advance the Daily Telegraph was looking for would come with Ivanhoe (1891), which opened to largely favourable reviews, but attracted some significant negative ones. For instance, J. A. Fuller Maitland wrote in The Times that the opera's "best portions rise so far above anything else that Sir Arthur Sullivan has given to the world, and have such force and dignity, that it is not difficult to forget the drawbacks which may be found in the want of interest in much of the choral writing, and the brevity of the concerted solo parts."[14] In her 1891 essay "Arthur Seymour Sullivan", Florence A. Marshall reviewed Sullivan's music up to that time, concluding that Sullivan was torn between his interests in comedy and tragedy. She wrote that he was "no dreamy idealist, but thoroughly practical ... apprehending and assimilating all the tendencies in the life of society around him, and knowing how to turn them all to account ... music is, in his hands, a plastic material, into which he can mold anything. His mastery of form and of instrumentation is absolute, and he wields them without the slightest semblance of effort. His taste is ... unerring; his perceptions of the keenest; his sense of humor infectious and irresistible."[15]

In the 1890s, Sullivan's successes were fewer and farther between. The ballet Victoria and Merrie England (1898) won praise from most critics:

Sir Arthur Sullivan's music is music for the people. There is no attempt made to force on the public the dullness of academic experience. The melodies are all as fresh as last year's wine, and as exhilarating as sparkling champagne. There is not one tune which tires the hearing, and in the matter of orchestration our only humorous has let himself run riot, not being handicapped with libretto, and the gain is enormous.... All through we have orchestration of infinite delicacy, tunes of alarming simplicity, but never a tinge of vulgarity, and a total absence of the cymbal-brassy combination which some ballets never do without.[16]

After The Rose of Persia (1899), the Daily Telegraph said that "The musician is once again absolutely himself", while the Musical Times opined that "it is music that to hear once is to want to hear again and again."[17]

In 1899, Sullivan composed a popular song, "The Absent-Minded Beggar", to a text by Rudyard Kipling, donating the proceeds of the sale to "the wives and children of soldiers and sailors" on active service in the Boer War. Fuller Maitland disapproved in The Times, but Sullivan himself asked a friend, "Did the idiot expect the words to be set in cantata form, or as a developed composition with symphonic introduction, contrapuntal treatment, etc.?"[18]

Posthumous reputation

If the musical establishment never quite forgave Sullivan for condescending to write music that was both comic and popular, he was, nevertheless, the nation's de facto composer laureate.[19] Sullivan was considered the natural candidate to compose a Te Deum for the end of the Boer War, which he duly completed, despite serious ill-health, but did not live to see performed.

Gian Andrea Mazzucato wrote this glowing summary of his career in The Musical Standard of 16 December 1899:

As regards music, the English history of the 19th century could not record the name of a man whose "life work" is more worthy of honour, study and admiration than the name of Sir Arthur Sullivan, whose useful activity, it may be expected, will extend considerably into the 20th century; and it is a debatable point whether the universal history of music can point to any musical personality since the days of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, whose influence is likely to be more lasting than the influence the great Englishman is slowly, but surely, exerting, and whose results shall be clearly seen, perhaps, only by our posterity. I make no doubt that when, in proper course of time, Sir Arthur Sullivan's life and works have become known on the continent, he will, by unanimous consent, be classed among the epoch-making composers, the select few whose genius and strength of will empowered them to find and found a national school of music, that is, to endow their countrymen with the undefinable, yet positive means of evoking in a man's soul, by the magic of sound, those delicate nuances of feeling which are characteristic of the emotional power of each different race.[20]

Likewise, Sir George Grove wrote, "Form and symmetry he seems to possess by instinct; rhythm and melody clothe everything he touches; the music shows not only sympathetic genius, but sense, judgement, proportion, and a complete absence of pedantry and pretension; while the orchestration is distinguished by a happy and original beauty hardly surpassed by the greatest masters.".[21]<

Over the next decade, however, Sullivan's reputation sank considerably. Shortly after the composer's death, J. A. Fuller Maitland took issue with the generally laudatory tone of most of the obituaries, citing the composer's failure to live up to the early praise of his Tempest music:

Among the lesser men who are still ranked with the great composers, there are many who may only have reached the highest level now and then, but within whose capacity it lies to attain great heights; some may have produced work on a dead-level of mediocrity, but may have risen on some special occasion to a pitch of beauty or power which would establish their claim to be numbered among the great. Is there anywhere a case quite parallel to that of Sir Arthur Sullivan, who began his career with a work which at once stamped him as a genius, and to the height of which he only rarely attained throughout life?....

Though the illustrious masters of the past never did write music as vulgar, it would have been forgiven them if they had, in virtue of the beauty and value of the great bulk of their productions. It is because such great natural gifts – gifts greater, perhaps, than fell to any English musician since the time of Purcell – were so very seldom employed in work worthy of them.... If the author of The Golden Legend, the music to The Tempest, Henry VIII and Macbeth cannot be classed with these, how can the composer of "Onward Christian Soldiers" and "The Absent-Minded Beggar" claim a place in the hierarchy of music among the men who would face death rather than smirch their singing robes for the sake of a fleeting popularity?[22]

Edward Elgar, to whom Sullivan had been particularly kind,[24] rose to Sullivan's defence, branding Fuller Maitland's obituary "the shady side of musical criticism... that foul unforgettable episode."[25] Fuller Maitland was later discredited when it was shown that he had falsified the facts, inventing a banal lyric, passing it off as genuine and condemning Sullivan for supposedly setting such inanity.[26] In 1929 Fuller Maitland admitted that he had been wrong in earlier years to dismiss Sullivan's comic operas as "ephemeral".[27]

In his History of Music in England (1907) Ernest Walker was even more damning of Sullivan than Fuller Maitland had been in 1901:

After all, Sullivan is merely the idle singer of an empty evening; with all his gift for tunefulness, he could never raise it to the height of a real strong melody of the kind that appeals to cultured and relatively uncultured alike as a good folk-song does – often and often on the other hand (but chiefly outside the operas) it sunk to mere vulgar catchiness. He laid the original foundations of his success on work that as a matter of fact he did extremely well; and it would have been incalculably better for the permanence of his reputation if he had realised this and set himself, with sincerity and self-criticism, to the task of becoming – as he might easily have become – a really great composer of musicianly light music. But anything like steadiness of artistic purpose was never one of his endowments, and without that, a composer, whatever his technical ability may be, is easily liable to degenerate into a mere popularity-hunting trifler. (Walker 1907, quoted in Eden 1992).

Fuller Maitland incorporated similar views in the second edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, which he edited, while Walker's History was re-issued in 1923 and 1956 with his earlier verdict intact. As late as 1966, Frank Howes, former music critic of The Times wrote:

Outside the Savoy operas, little enough of Sullivan has survived... Yet a post-mortem is a valuable form of inquest, not only to ascertain the cause of death, but to discover why Sullivan's music as a whole had not in it the seeds of the revival that was on the verge of taking place. The lack of sustained effort, that is artistic effort proved by vigorous self-criticism, is responsible for the impression of weakness, the streaks of poor stuff among the better metal, and the consequent general ambiguity that is left by his music. His contemporaries deprecated his addiction to high life, the turf, and an outward lack of seriousness. Without adopting the simplified morality of the women's magazines, it is possible to urge that his contemporaries were really right, in that such addiction implied a fundamental lack of seriousness towards his art. (Howes 1966, quoted in Eden 1992).

There were other writers who rose to praise Sullivan. For example, Thomas F. Dunhill wrote an entire chapter of his 1928 book, Sullivan's Comic Operas, titled "Mainly in Defence", which reads in part:

It should not be necessary to defend a writer who is so firmly established in popular esteem that his best works are more widely known and more keenly appreciated over a quarter of a century after his death than they were at any period during his lifetime.... But no critical appreciation of Sullivan can be attempted to-day which does not, from the first, adopt a defensive attitude, for his music has suffered in an extraordinary degree from the vigorous attacks which have been made upon it in professional circles. These attacks have succeeded in surrounding the composer with a kind of barricade of prejudice which must be swept away before justice can be done to his genius.[28]

Gervase Hughes (1959) picked up the trail where Dunhill left off:

Dunhill's achievement was that of a pioneer, a preliminary skirmish in a campaign whose advance has yet to be implemented. Today there may be few musicians for whom — as for Ernest Walker — Sullivan is merely 'the idle singer of an empty evening'; there are many who, while acknowledging his great gifts, tend to take them for granted.... The time is surely ripe for a comprehensive study of his music as a whole, which, while recognising that the operettas "form his chief title to fame" will not leave the rest out of account, and while taking note of his weaknesses (which are many) and not hesitating to castigate his lapses from good taste (which were comparatively rare) will attempt to view them in perspective against the wider background of his sound musicianship.[29]

Recent views

In recent years, Sullivan's work outside of the Savoy Operas has begun to be re-assessed. It has only been since the late 1960s that a quantity of his non-Savoy music has been professionally recorded. The Symphony in E had its first professional recording in 1968; his solo piano and chamber music in 1974; the cello concerto in 1986; Kenilworth in 1999; The Martyr of Antioch in 2000; The Golden Legend in 2001. In 1992 and 1993, Naxos released four discs featuring performances of Sullivan's ballet music and his incidental music to plays. Of his operas apart from Gilbert, Cox and Box (1961 and several later recordings), The Zoo (1978), The Rose of Persia (1999), and The Contrabandista (2004) have had professional recordings.

In recent decades, several publishers have issued scholarly critical editions of Sullivan's works, including Ernst Eulenburg (The Gondoliers), Broude Brothers (Trial by Jury and H.M.S. Pinafore), David Russell Hulme for Oxford University Press (Ruddigore), Robin Gordon-Powell at The Amber Ring (The Masque at Kenilworth, the Marmion overture, the Imperial March, The Contrabandista, The Prodigal Son, On Shore and Sea, Macbeth incidental music, and Ivanhoe), and R. Clyde (Cox and Box, Haddon Hall, Overture "In Memoriam", Overture di Ballo, and The Golden Legend).

In a 2000 article for the Musical Times, Nigel Burton wrote:

We must assert that Sullivan has no need to be "earnest" (though he could be), for he spoke naturally to all people, for all time, of the passions, sorrows and joys which are forever rooted in the human consciousness. He believed, deeply, in the moral expressed at the close of Cherubini's Les deux journées: that the human being's prime duty in life is to serve humanity. It is his artistic consistency in this respect which obliges us to pronounce him our greatest Victorian composer. Time has now sufficiently dispersed the mists of criticism for us to be able to see the truth, to enjoy all his music, and to rejoice in the rich diversity of its panoply. Now, therefore, one hundred years after his death, let us resolve to set aside the "One-and-a-half-hurrahs" syndrome once and for all, and, in its place, raise THREE LOUD CHEERS.[26]

Notes

- ↑ Quoted in Jacobs, p. 28

- ↑ The Times, quoted in Jacobs, p. 42

- ↑ Jacobs, p. 49

- ↑ Letter of 22 December 1869, quoted in Allen and Gale, p. 32

- ↑ Quoted in Allen, p. 30

- ↑ Figaro, quoted in Allen, pp. 49–50

- ↑ 25 October 1880, quoted in Jacobs, p. 149

- ↑ Quoted in Allen, p. 176

- ↑ William Beatty-Kingston, Theatre, 1 January 1883, quoted in Baily 1966, p. 246

- 1 2 Baily, p. 250

- ↑ Quoted in Jacobs, p. 247

- ↑ Quoted in Harris, p. IV

- ↑ Quoted in Allen, p. 312

- ↑ Quoted in Jacobs, p. 331

- ↑ Marshall, Florence A. "Arthur Seymour Sullivan", Famous Composers and Their Works, vol. 1, Millet Co.,1891

- ↑ Quoted in Tillett 1998, p. 26

- ↑ Quoted in Jacobs, p. 397

- ↑ Quoted in Jacobs, p. 396

- ↑ Maine, Basil, Elgar, Sir Edward William, 1949, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography archive, accessed 20 April 2010 (subscription required).

- ↑ Quoted in the Sir Arthur Sullivan Society Journal, No. 34, Spring 1992, pp. 11–12

- ↑ "Arthur Sullivan", The Musical Times (1 December 1900), pp. 785–87 (subscription required)

- ↑ Eden 1992, quoting Cornhill March 1901, pp. 301, 309

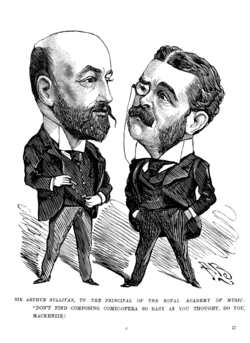

- ↑ Mackenzie wrote the comic opera His Majesty in 1897. The caption reads, "Don't find composing Comic-Opera so easy as you thought, do you, Mackenzie?"

- ↑ Young, p. 264

- ↑ Quoted in Young 1971, p. 264

- 1 2 Burton, Nigel. "Sullivan Reassessed: See How the Fates", The Musical Times, Winter 2000), pp. 15–22 (subscription required)

- ↑ "Light Opera", The Times, 22 September 1934, p. 10

- ↑ Dunhill 1928, p. 13

- ↑ Hughes, p. 6

Bibliography

- Ainger, Michael (2002). Gilbert and Sullivan – A Dual Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514769-3.

- Allen, Reginald; Gale R. D'Luhy (1975). Sir Arthur Sullivan – Composer & Personage. New York: The Pierpont Morgan Library.

- Bradley, Ian C (2005). Oh Joy! Oh Rapture! The Enduring Phenomenon of Gilbert and Sullivan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516700-7.

- Crowther, Andrew (2000). Contradiction Contradicted – The Plays of W. S. Gilbert. Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-3839-2.

- Dunhill, Thomas F. (1928). Sullivan's Comic Operas – A Critical Appreciation. London: Edward Arnold & Co.

- Harris, Roger, ed. (1986). The Golden Legend. Chorleywood, Herts., UK: R. Clyde.

- Hughes, Gervase (1959). The Music of Sir Arthur Sullivan. London: Macmillan & Co Ltd. * *Jacobs, Arthur (1986). Arthur Sullivan – A Victorian Musician. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-282033-8.

- Lawrence, Arthur (1899). Sir Arthur Sullivan, Life Story, Letters and Reminiscences. London: James Bowden. This book is available online here.

- Shaw, Bernard, ed. Dan Laurence. (1981) Shaw's Music: The Complete Music Criticism of Bernard Shaw, Volumes I (1876–1890) and II (1890–1893). London, The Bodley Head, 1981, ISBN 0-370-30247-8 and 0370302494

- Stedman, Jane W. (1996). W. S. Gilbert, A Classic Victorian & His Theatre. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816174-3.

- Young, Percy M. (1971). Sir Arthur Sullivan. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.