Galactose

| |||

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 59-23-4 | |||

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image | ||

| ChEBI | CHEBI:28061 | ||

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL300520 | ||

| ChemSpider | 388480 | ||

| 4646 | |||

| KEGG | D04291 | ||

| MeSH | Galactose | ||

| PubChem | 439357 | ||

| UNII | X2RN3Q8DNE | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H12O6 | |||

| Molar mass | 180.156 g mol−1 | ||

| Density | 1.723 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 167 °C (333 °F; 440 K) | ||

| 683.0 g/L | |||

| Pharmacology | |||

| V04CE01 (WHO) V08DA02 (WHO) (microparticles) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704 | |||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Galactose (galacto- + -ose, "milk sugar"), sometimes abbreviated Gal, is a monosaccharide sugar that is less sweet than glucose and fructose. It is a C-4 epimer of glucose.

Galactan is a polymeric form of galactose found in hemicellulose. Galactan can be converted to galactose by hydrolysis.

Structure and isomerism

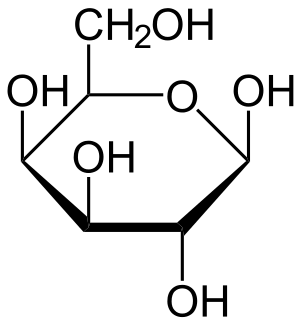

Galactose exists in both open-chain and cyclic form. The open-chain form has a carbonyl at the end of the chain.

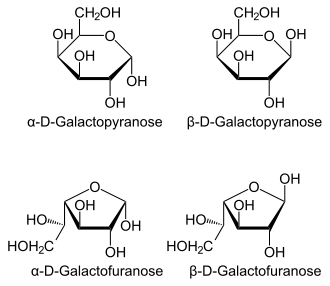

Four isomers are cyclic, two of them with a pyranose (six-membered) ring, two with a furanose (five-membered) ring. Galactofuranose occurs in bacteria, fungi and protozoa ,[1] and is recognized by a putative chordate immune lectin intelectin through its exocyclic 1,2-diol. In the cyclic form there are two anomers, named alpha and beta, since the transition from the open-chain form to the cyclic form involves the creation of a new stereocenter at the site of the open-chain carbonyl. In the beta form, the alcohol group is in the equatorial position, whereas in the alpha form, the alcohol group is in the axial position.[2]

Relationship to lactose

Galactose is a monosaccharide. When combined with glucose (monosaccharide), through a condensation reaction, the result is the disaccharide lactose. The hydrolysis of lactose to glucose and galactose is catalyzed by the enzymes lactase and β-galactosidase. The latter is produced by the lac operon in Escherichia coli.

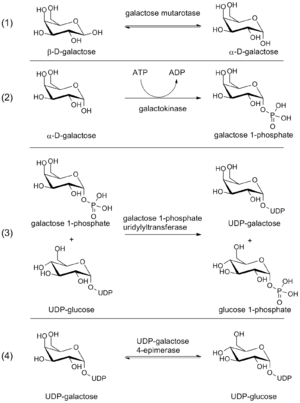

In nature, lactose is found primarily in milk and milk products. Consequently, various food products made with dairy-derived ingredients, e.g. breads and cereals, can contain lactose.[3] Galactose metabolism, which converts galactose into glucose, is carried out by the three principal enzymes in a mechanism known as the Leloir pathway. The enzymes are listed in the order of the metabolic pathway: galactokinase (GALK), galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT), and UDP-galactose-4’-epimerase (GALE).

In human lactation, glucose is changed into galactose via hexoneogenesis to enable the mammary glands to secrete lactose. However, most lactose in breast milk is synthesized from galactose taken up from the blood, and only 35±6% is made from galactose from de novo synthesis. [4] Glycerol also contributes some to the mammary galactose production.[5]

Metabolism

| Metabolism of common monosaccharides and some biochemical reactions of glucose |

|---|

|

Glucose is the primary metabolic fuel for humans. It is more stable than galactose and is less susceptible to the formation of nonspecific glycoconjugates, molecules with at least one sugar attached to a protein or lipid. Many speculate that it is for this reason that a pathway for rapid conversion from galactose to glucose has been highly conserved among many species.[6]

The main pathway of galactose metabolism is the Leloir pathway; humans and other species, however, have been noted to contain several alternate pathways, such as the De Ley Doudoroff pathway. The Leloir pathway consists of the latter stage of a two-part process that converts β-D-galactose to UDP-glucose. The initial stage is the conversion of β-D-galactose to α-D-galactose by the enzyme, mutarotase (GALM). The Leloir pathway then carries out the conversion of α-D-galactose to UDP-glucose via three principal enzymes: Galactokinase (GALK) phosphorylates α-D-galactose to galactose-1-phosphate, or Gal-1-P; Galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT) transfers a UMP group from UDP-glucose to Gal-1-P to form UDP-galactose; and finally, UDP galactose-4’-epimerase (GALE) interconverts UDP-galactose and UDP-glucose, thereby completing the pathway.[7]

Galactosemia is an inability to properly break down galactose due to a genetically inherited mutation in one of the enzymes in the Leloir pathway. As a result, the consumption of even small quantities is harmful to galactosemics.[8]

Sources

Galactose is found in dairy products, sugar beets, other gums and mucilages. It is also synthesized by the body, where it forms part of glycolipids and glycoproteins in several tissues; and is a by-product from the third-generation ethanol production process (from macroalgae).

Clinical significance

Chronic systemic exposure of mice, rats, and Drosophila to D-galactose causes the acceleration of senescence (aging) and has been used as an aging model.[9] [10] Two studies have suggested a possible link between galactose in milk and ovarian cancer.[11][12] Other studies show no correlation, even in the presence of defective galactose metabolism.[13][14] More recently, pooled analysis done by the Harvard School of Public Health showed no specific correlation between lactose-containing foods and ovarian cancer, and showed statistically insignificant increases in risk for consumption of lactose at ≥30 g/d.[15] More research is necessary to ascertain possible risks.

Some ongoing studies suggest galactose may have a role in treatment of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (a kidney disease resulting in kidney failure and proteinuria).[16] This effect is likely to be a result of binding of galactose to FSGS factor.[17]

Galactose is a component of the antigens present on blood cells that determine blood type within the ABO blood group system. In O and A antigens, there are two monomers of galactose on the antigens, whereas in the B antigens there are three monomers of galactose.[18]

A disaccharide composed of two units of galactose, galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal), has been recognized as a potential allergen present in mammal meat. Alpha-gal allergy may be triggered by lone star tick bites.

History

In 1855, E. O. Erdmann noted that hydrolysis of lactose produced a substance besides glucose.[19] Galactose was first isolated and studied by Louis Pasteur in 1856.[20] He called it "lactose".[21] In 1860, Berthelot renamed it "galactose" or "glucose lactique".[22][23] In 1894, Emil Fischer and Robert Morrell determined the configuration of galactose.[24]

See also

References

- ↑ Nassau et al. Galactofuranose Biosynthesis in Escherichia coli K-12:... Journal of Bacteriology, Feb. 1996, p. 1047–1052

- ↑ Ophardt, C. Galactose

- ↑ Staff (June 2009). "Lactose Intolerance - National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse". digestive.niddk.nih.gov. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ↑ Sunehag A, Tigas S, Haymond MW (January 2003). "Contribution of plasma galactose and glucose to milk lactose synthesis during galactose ingestion". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88 (1): 225–9. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-020768. PMID 12519857.

- ↑ Sunehag AL, Louie K, Bier JL, Tigas S, Haymond MW (January 2002). "Hexoneogenesis in the human breast during lactation". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87 (1): 297–301. doi:10.1210/jc.87.1.297. PMID 11788663.

- ↑ Fridovich-Keil JL, Walter JH. "Galactosemia". The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease.

|chapter=ignored (help)

a 4 b 21 c 22 d 22 - ↑ Bosch AM (August 2006). "Classical galactosaemia revisited". J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 29 (4): 516–25. doi:10.1007/s10545-006-0382-0. PMID 16838075.

a 517 b 516 c 519 - ↑ Gerard T Berry. "Classic Galactosemia and Clinical Variant Galactosemia". nih.gov. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ↑ Pourmemar E, Majdi A, Haramshahi M, Talebi M, Karimi P, Sadigh-Eteghad S (2017). "Intranasal Cerebrolysin Attenuates Learning and Memory Impairments in D-galactose-Induced Senescence in Mice". Experimental Gerontology. 87: 16–22. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2016.11.011. PMID 27894939.

- ↑ Cui, X.; Zuo, P.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Hu, Y.; Long, J.; Packer, L.; Liu, J. (2006). "Chronic systemic D-galactose exposure induces memory loss, neurodegeneration, and oxidative damage in mice: protective effects of R-alpha-lipoic acid". Journal of neuroscience research. 84 (3): 647–654. doi:10.1002/jnr.20899. PMID 16710848.

- ↑ Cramer D (1989). "Lactase persistence and milk consumption as determinants of ovarian cancer risk". Am J Epidemiol. 130 (5): 904–10. PMID 2510499.

- ↑ Cramer D, Harlow B, Willett W, Welch W, Bell D, Scully R, Ng W, Knapp R (1989). "Galactose consumption and metabolism in relation to the risk of ovarian cancer". Lancet. 2 (8654): 66–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90313-9. PMID 2567871.

- ↑ Marc T. Goodman; Anna H. Wu; Ko-Hui Tung; Katharine McDuffie; Daniel W. Cramer; Lynne R. Wilkens; Keith Terada; Juergen K. V. Reichardt; Won G. Ng (2002). "Association of Galactose-1-Phosphate Uridyltransferase Activity and N314D Genotype with the Risk of Ovarian Cancer". Am. J. Epidemiol. 156 (8): 693–701. doi:10.1093/aje/kwf104. PMID 12370157.

- ↑ Fung, W. L. Alan; Risch, Harvey; McLaughlin, John; Rosen, Barry; Cole, David; Vesprini, Danny; Narod, Steven A. (2003). "The N314D Polymorphism of Galactose-1-Phosphate Uridyl Transferase Does Not Modify the Risk of Ovarian Cancer". Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 12 (7): 678–80. PMID 12869412.

- ↑ Genkinger, Jeanine M.; Hunter, David J.; Spiegelman, Donna; Anderson, Kristin E.; Arslan, Alan; Beeson, W. Lawrence; Buring, Julie E.; Fraser, Gary E.; Freudenheim, Jo L.; Goldbohm, R. Alexandra; Hankinson, Susan E.; Jacobs, David R. Jr.; Koushik, Anita; Lacey, James V. Jr.; Larsson, Susanna C.; Leitzmann, Michael; McCullough, Marji L.; Miller, Anthony B.; Rodriguez, Carmen; Rohan, Thomas E.; Schouten, Leo J.; Shore, Roy; Smit, Ellen; Wolk, Alicja; Zhang, Shumin M.; Smith-Warner; Stephanie A. (2006). "Dairy Products and Ovarian Cancer: A Pooled Analysis of 12 Cohort Studies". Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 15 (2): 364–372. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0484. PMID 16492930.

- ↑ "FSGS permeability factor-associated nephrotic syndrome: remission after oral galactose therapy" (PDF). oxfordjournals.org. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ↑ Ellen T. McCarthy. "Circulating Permeability Factors in Idiopathic Nephrotic Syndrome and Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis". asnjournals.org. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ↑ Peter H. Raven; George B. Johnson (1995). Carol J. Mills, ed. Understanding Biology (3rd ed.). WM C. Brown. p. 203. ISBN 0-697-22213-6.

- ↑ See:

- Eduard Otto Erdmann (1855) Dissertation: Dissertatio de saccharo lactico et amylaceo [Dissertation on milk sugar and starch](University of Berlin).

- Jahresbericht über die Fortschritte der reinen, pharmaceutischen und technischen Chemie, … [Annual report on progress in pure, pharmaceutical, and technical chemistry, … ] (1855), pages 671-673; see especially p. 673.

- ↑ Pasteur (1856) "Note sur le sucre de lait" (Note on milk sugar), Comptes rendus, 42 : 347-351.

- ↑ Pasteur (1856), p. 348. From page 348: "Je propose de le nommer lactose." (I propose to name it lactose.)

- ↑ Marcellin Berthelot, Chimie organique fondée sur la synthèse [Organic chemistry based on synthesis] (Paris, France: Mallet-Bachelier, 1860), vol. 2, pp. 248-249.

- ↑ "Galactose" — from the Ancient Greek γάλακτος (gálaktos, “milk”).

- ↑ Emil Fischer and Robert S. Morrell (1894) "Ueber die Configuration der Rhamnose und Galactose" (On the configuration of rhamnose and galactose), Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin, 27 : 382-394. The configuration of galactose appears on page 385.