Discrete trial training

Discrete trial training (DTT; also called discrete trial instruction or DTI) is a form of applied behavior analysis (ABA) that was developed by Ivar Lovaas at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). DTT is a practitioner-led, structured instructional procedure that breaks tasks down into simple subunits to shape new skills. Often employed up to 6-7 hours per day for children with autism, the technique relies on the use of prompts, modeling, and positive reinforcement strategies to facilitate the child's learning. It is also noted for its previous use of aversives to punish unwanted behaviors.

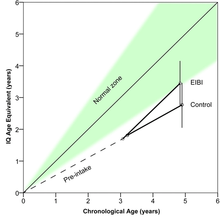

Lovaas spent most of his career conducting groundbreaking research on the use of this methodology to teach autistic children. As of 2005,[2][3] two studies have shown that approximately 93% of children with autism under the age of 5 who received structured early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI), or 30-40 hours per week of DTT, had gained significant language, intellectual, and adaptive skills. The first, a seminal study by Lovaas (1987) reported that 47% of such children acquired typical language and academic skills, and were placed into mainstream classrooms at age 7. Follow-up measures in 1993 showed that all but one of the 'best outcome' children maintained their gains and were functioning socially at the same level as their typically developing adolescent peers.[4] The study, later, received praise in a mental health report by the US Surgeon General in 1999.

The US National Research Council classified structured combined with more naturalistic EIBIs as "well-established" for the treatment of autism in 2001. Since 2009, the American Academy of Pediatrics identified EIBI and the early start denver model (ESDM)—a comprehensive developmental intervention overlapping with ABA—as the only evidence-based clinical interventions for the population.

Implementation

The Lovaas approach is a highly structured comprehensive program that relies heavily on discrete trial training (DTT) methods. Within Lovaas therapy, DTT is used to reduce stereotypical autistic behaviours through extinction and the provision of socially acceptable alternatives to self-stimulatory behaviors. Intervention can start when a child is as young as three and can last from two to six years. Progression through goals of the program are determined on an individual basis and are not determined by which year the client has been in the program. The first year seeks to reduce self-stimulating ("stimming") behavior, teaches imitation, establishes playing with toys in their intended manner, and integration of the family into the treatment protocol. The second year teaches early expressive and abstract linguistic skills, peer interaction, basic socializing skills, and strives to include the individual's community in the treatment to optimize mainstreaming while eliminating any possible sources of stigmatization. The third year focuses on emotional expression and variation in addition to observational learning, and pre-academic skills such as reading writing, and arithmetic. Rarely is the technique implemented for the first time with adults.[2][3]

The Lovaas method is ideally performed five to seven days a week with each session lasting from five to seven hours, totaling an average of 35–40 hours per week.[5] Each session is divided into trials with intermittent breaks. The trials do not have a specified time limit to allow for a natural conclusion when the communicator feels the child is losing focus. Each trial is composed of a series of prompts (verbal, gestural, physical, etc.) that are issued by the "communicator" who is positioned directly across the table from the individual receiving treatment.:) These prompts can range from "put in"," put on"," show me"," give to me" and so on, in reference to an object, color, simple imitative gesture, etc. The concept is centered on shaping the child to correctly respond to the prompts, increasing the attentive ability of the individual, and mainstreaming the child for academic success. Should the child fail to respond to a prompt, a "prompter," seated behind the child, uses either a partial-, a simple nudge or touch on the hand or arm or a full-, hand over hand assistance until the prompt has been completed, physical guide to correct the individual's mistake or non-compliance. Each correct response is reinforced with verbal praise, an edible, time with a preferred toy, or any combination thereof.[2][3][4] DTT is often used in conjunction with the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) as it primes the child for an easy transition between treatment types. The PECS program serves as another common intervention technique used to mainstream individuals with autism.[6] As many as 25% of individuals with autism have no functional speech, the remainder typically display pronounced phonological and grammatical deficits in addition to a limited vocabulary.[7] The program teaches spontaneous social communication through symbols and/or pictures by relying on ABA techniques.[8] PECS operates on a similar premise to DTT in that it uses systematic chaining to teach the individual to pair the concept of expressive speech with an object. It is structured in a similar fashion to DTT, in that each session begins with a preferred reinforcer survey to ascertain what would most motivate the child and effectively facilitate learning.[8]

Effectiveness

More than 500 articles have been published showing the effectiveness of the Lovaas technique for children with autism.[9] Questions concerning the effectiveness of the method involve reports of recovery from autism, based on the intervention.

The Lovaas technique was developed based on research performed by Ivar Lovaas and his assistants.[3] This research reported that 47% of those children who had received the Lovaas treatment protocol of an average of 40 hours of intensive therapy, were mainstreamed into regular classrooms, and were classified as "indistinguishable" from their peers in follow-up studies. Although subsequent studies have shown that intensive behavioral therapy clearly benefited children with autism, it has been claimed that Lovaas's original claims of effectiveness were overstated.[10] A 2005 California study found that early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI), the Lovaas technique used for very young children, was substantially more effective for preschool children with autism than the mixture of methods provided in many programs.[11] However, this study did not use random assignment or a uniform assessment protocol, and provided limited information about the intervention, making it difficult to replicate.[12]

Smith et al. (2002)[13] performed a preliminary study of nine high-functioning children with autism, all of whom were previous recipients of early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI), of ages five to seven in free play settings. The purpose was to assess the effects of EIBI on solitary activities, ritualistic behaviors, and social activity when exposed to the two experimental groups. Each child participated in four one-hour sessions consisting of 15 minute periods of play with either a typically developing peer or a lower functioning child with autism who had major deficits in pragmatic communication, social interaction and self-care. The children had never met prior to these experimental sessions. The period of play began with 15 minutes of play with either the typically developed (TD) peer or the developmentally disabled (DD) peer, and alternated accordingly in one of two variations: TD-DD-TD-DD or DD-TD-DD-TD. Observers rated play on five criteria: i. interactive toy play, ii. interactive speech, iii. solitary toy play, iv. solitary speech, and v. self-stimulation. Data showed the high-functioning children displayed significantly more instances of interactive play and interactive speech when paired with the typically developed peer.[13]

The Lovaas technique is best generalized when paired with natural settings, and the implementation is clearly structured.[14] A good sense of direction is needed when planning for intervention. Although this is one approach, many children on the autism spectrum learn differently and this needs to be taken into account to ensure the Lovaas approach is effective for all. It has been shown that, for some children with autism, typical peer interaction can increase the chance of leading a normal life. Lovaas techniques are cost effective for administrators.[15]

Aversives

While the therapy has always relied principally on positive reinforcement of preferred behavior, Lovaas's original technique also included more extensive use of aversives such as striking, shouting, or using electrical shocks.[16] These procedures have been widely abandoned for over a decade. A review of literature by autistic activist Michelle Dawson asserts that the method has become less effective since these stimuli were abandoned.[17] Only one institution, the Judge Rotenberg Center, still employs electric shocks as aversives—a practice that continues to cause them considerable legal and political controversy.[18] This has led some to question whether the use of aversives by those in behavioral institutions should be limited to those who are licensed (see licensed behavior analyst).

Cost of care

A concern that parents have brought up regarding Lovaas is the cost, which in April 2002 amounted to about US$4,200 per month ($50,000 annually per child).[19] In addition, the 20–40 hours per week intensity of the program, often conducted at home, may place additional stress on already challenged families.[9]

Another study estimated the expenses of a three-year period of DTT to total a conservative cost of $20,000 and the extreme cost of $60,000, with a yearly average of $40,000. These costs were based on a sliding scale model that would be adjusted accordingly to socio-economic status and parental involvement. Yearly expenditures were predicted to drop to an average of $22,500 a year when parents and family became involved in the process. Additional family involvement would subsequently alleviate case manager and paraprofessional hours by assuming their roles in the process. The upfront costs of DTT for the state of Texas would initially amount to $67,500 for three years compared to the currently state budgeted $33,000 for Special Education. The difference is predicted to be recovered within five years of the initial implementation of the program. Texas would experience a 72% reduction in expenses in the 15 year offset following the conclusion of DTT, amounting to a total savings of $84,300 per child.[20][21]

However, in the United States, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires school districts to provide a Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) to all children over the age of three. Many administrative rulings and court decisions have found 35–40 hours per week of EIBI to be FAPE. Parents may wish to consider hiring an attorney or advocate if their school district denies EIBT.

Thomas et al. (2007)[21] conducted a survey study that involved 383 families with children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder from North Carolina. Three quarters of these families reported using a major treatment plan. Of these, college or graduate degree holding parents were two to four times more likely to use a neurologist and/or PECS. Annual incomes of $50,000 or more had higher rates of using developmental pediatricians and speech/language therapists. Racial and ethnic minorities were half as likely to see a case manager. These families also had a quarter of the odds of seeing a psychologist, developmental pediatrician, or implementing sensory integration.[21] This supports several other national studies that concluded racial and ethnic families, parents with a low degree of education, and those not residing in a metropolitan area were more likely to receive limited care, utilize a less diverse range of services and less likely to follow a major treatment plan.[22][23] Both the national studies and the North Carolinian study yielded a correlation between high stress levels and amount of services sought.[21][22][23]

Families that did not identify with a major treatment approach had one fifth to one half the odds of using support of friends and family in providing care. Therapeutic support services (PECS, parent support classes, sensory integration, casein- and gluten-free diets) were also one fifth to one half as likely to be used compared to families identifying with major treatment plans.[21]

Insurance coverage is another major determinant in the amount of support services received. Recipients of Medicaid or other forms of public health insurance have 2-11 times the odds of using services that are considered medically necessary. Utilization of respite, PECS, case managers, speech or language therapists also increases markedly in this bracket compared to families with private insurance.[21]

Rising costs in education and the provision of adequate care for developmentally disabled individuals have been a continuing concern for state policy makers and tax payers alike. A study was conducted on cost comparison of 18 years of traditional Special Education on Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention (EIBI) for children with autism. The Texas state budget for the year 2002 allotted $11,000 per child for Special Education. The study suggested the state would save an average of $208,500 per child over an 18-year period by implementing DTT in early childhood, effectively curbing or eliminating future special needs costs by preparing the child academically for mainstreaming. This amounted to a potential total savings of $2.9 billion over an 18-year period for a cohort consisting of 10,000 children with autism.[20]

Criticisms

Gresham and MacMillar (1998)[24] specifically cite a lack of a true experimental design in Lovaas' (1987) experiment on early intervention. They charge that he instead implemented a quasi-experimental design of matched pairs regarding the distribution of subjects within the experimental and control groups. Gresham and MacMillar (1998)[24] also state a lack of a true representation of autism in that the subjects were neither randomly sampled from the population of individuals with autism nor were they randomly assigned to treatment groups. The internal validity of the study was also called into question due to the possibility of skewed data resulting from three influential threats. Instrumentation, changes or variations in measurement of procedures over time, was argued to have been altered in both the pre-test and post-test conditions which were confounded by a differentiation in ascertaining cognitive abilities and intelligence of the subjects. The pre-test utilized four measures of cognitive ability and mental development. Five of the subjects' intelligence was determined through a parent-reported measure of adaptive behavior. All of the subjects were post-tested three years later using five other measures of intelligence and cognitive ability. Long-term follow-up was assessed with three measurements of (1) intelligence, (2) nonverbal reasoning, and (3) receptive language. The original three measurements during the testing phase were determined by (1) IQ score, (2) class placement, and (3) promotion/retention.[24] External validity was called into question concerning sample characteristics. Lovaas' (1987) criteria for acceptance into the program required a psychological mental age greater than 11 months and a chronological age less than 46 months in the case of echolalic children. Schopler et al. (1989)[25] purport that if both the intellectual and echolalia criteria were rigidly adhered to at the North Carolina institute, approximately 57% of the referrals would have been excluded from the program.

Other criticisms include a failure to operationally define the use of the term 'reinforcement' for compliance, the use of a Pro-rated Mental Age, and the statistical regression of the child's IQ over time.[24][26] Boyd (1998)[27] addressed the potential impact of a disproportionate sex ratio of females to males on the control group's mean IQ score. One study showed females with autism displayed slightly lower levels of functioning in comparison to their male counterparts.[28]

In a rejoinder to Boyd's (1998)[27] article that cited an unequal sex ratio as a source of error, Lovaas (1998)[29] listed three reasons as to why the disproportionate ratio's influence on the data was negligible. The autistic population at the time had a ratio of 4:1. Lovaas (1998)[29] argued that the ratios for the experimental group, control group 1, and control group 2 of 16:3, 11:8, and 16:5, respectively, were in fact near the expected ratio scale of the general population with the exception of control group 1. The second argument lay in the studies Boyd (1998)[27] referenced in regards to low intellectual performance in females diagnosed with autism. One of the studies admitted to having a female subject with Rett disorder, a condition that showed little responsiveness to intensive early behavioral intervention. Lovaas (1998)[29] concluded by proposing that males may more readily meet diagnostic criteria for autism because of certain salient characteristics inherent in the sex while the subtleties in their female counterparts may be overlooked.

See also

References

- ↑ Klintwall Eldevik Eikeseth (2015). "Narrowing The Gap – Effects of Type and Intensity of Intervention on Developmental Trajectories in Autism". Autism: International Journal of Research and Practice. doi:10.1177/1362361313510067.

- 1 2 3 Lovaas OI (February 1987). "Behavioral treatment and normal educational and intellectual functioning in young children with autism". J Consult Clin Psychol. 55 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.55.1.3. PMID 3571656.

- 1 2 3 4 Sallows GO, Graupner TD (November 2005). "Intensive behavioral treatment for children with autism: four-year outcome and predictors". Am J Ment Retard. 110 (6): 417–38. doi:10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110[417:IBTFCW]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0895-8017. PMID 16212446.

- 1 2 McEachin JJ, Smith T, Lovaas OI (January 1993). "Long-term outcome for children with autism who received early intensive behavioral treatment". Am J Ment Retard. 97 (4): 359–72; discussion 373–91. PMID 8427693.

- ↑ Jacobson JW, Mulick JA, Green G (1998). "Cost-benefit estimates for early intensive behavioral intervention for young children with autism: General model and single state case". Behavioral Interventions. 13: 201–226. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-078x(199811)13:4<201::aid-bin17>3.0.co;2-r.

- ↑ Howlin P, Gordon RK, Pasco G, Wade A, Charman T (May 2007). "The effectiveness of Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) training for those who teach children with autism: a pragmatic, group randomised controlled trial". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 48 (5): 473–81. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01707.x. PMID 17501728.

- ↑ Volkmar FR, Lord C, Baily A, Schultz RT, Klin A. (2004). Autism and pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45: 135-170 .

- 1 2 Frost LA, Bondy AS. (2002). The Picture Exchange Communication System Training Manual, Second Edition. Newark, DE: Pyramid Educational Products Inc

- 1 2 Lovaas O.I.; Wright Scott (2006). "A Reply to Recent Public Critiques…". JEIBI. 3 (2): 221–229.

- ↑ Francis K (2005). "Autism interventions: a critical update" (PDF). Dev Med Child Neurol. 47 (7): 493–99. doi:10.1017/S0012162205000952. PMID 15991872.

- ↑ Howard JS, Sparkman CR, Cohen HG, Green G, Stanislaw H (2005). "A comparison of intensive behavior analytic and eclectic treatments for young children with autism". Res Dev Disabil. 26 (4): 359–83. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2004.09.005. PMID 15766629.

- ↑ Schoneberger T (2006). "EIBT research after Lovaas (1987): a tale of two studies". J Speech-Lang Pathol Appl Behav Anal. 1 (3): 210–217.

- 1 2 Smith T, Lovaas NW, Lovaas OI (2002). "Behaviors of children with high-functioning autism when paired with typically developing versus delayed peers: A preliminary study". Behavioral Interventions. 17: 129–143. doi:10.1002/bin.114.

- ↑ Ferraioli, Suzannah; Hughes, Carrie; Smith, Tristram (2005). "A Model for Problem Solving in Discrete Trial Training for Children With Autism". JEIBI. 2 (4): 224–229.

- ↑ Jacobson, J. W. (2000). "Converting to a Behavior Analysis Format for Autism Services: Decision-Making for Educational Administrators, Principals, and Consultants". The Behavior Analyst Today. 1 (3): 6–16. doi:10.1037/h0099889.

- ↑ Moser D, Grant A (1965-05-07). "Screams, slaps and love". Life.

- ↑ Dawson, Michelle (2004-01-18). "The Misbehaviour of Behaviourists: Ethical Challenges to the Autism-ABA Industry". Retrieved 2007-06-10. Note that this is a self-published document, and has not been subject to a peer review.

- ↑ Gonnerman, Jennifer (20 August 2007). "School of Shock". Mother Jones Magazine. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- ↑ Elder, Jennifer Harrison (2002). "Current treatments in autisms: Examining scientific evidence and clinical implications". Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 34 (2): 67–73. doi:10.1097/01376517-200204000-00005. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- 1 2 Chasson GS, Harris GE, Nealy WT (2007). "Cost comparison of early intensive behavioral intervention and special education for children with autism". Journal of Family Studies. 16: 401–441. doi:10.1007/s10826-006-9094-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Thomas, KC; Ellis, AR; McLaurin, C; Daniels, J; Morrissay, JP (2007). "Access to care for autism related Services". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 37: 1902–1912. doi:10.1007/j10803-006-0323-7.

- 1 2 Hurth J, Shaw E, Izeman S, Whaley K, Rogers S (1999). "Areas of agreement about effective practices among programs serving young children with autism spectrum disorders". Infants and Young Children. 12: 17–26. doi:10.1097/00001163-199910000-00003.

- 1 2 Rogers S (1998). "Neuropsychology of autism in young children and its implications for early intervention". Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 4: 104–112. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-2779(1998)4:2<104::aid-mrdd7>3.3.co;2-m.

- 1 2 3 4 Gresham FM, MacMillar DL (1998). "Early intervention project: Can its claims be substantiated and its effects replicated?". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 28 (1): 5–13. doi:10.1023/A:1026002717402. PMID 9546297.

- ↑ Schopler E, Short A, Meisbov G (1989). "Relation of behavioral treatment to "normal functioning": Comment on lovaas". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 57: 162–164. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.57.1.162.

- ↑ Eikeseth S (2001). "Recent critiques of the ucla young autism project". Behavioral Interventions. 16: 249–264. doi:10.1002/bin.095.

- 1 2 3 Boyd RD (1998). "Sex as possible source of group inequivalence in Lovaas (1998)". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 28: 211–215. doi:10.1023/A:1026065321080. PMID 9656132.

- ↑ Lord C, Schopler E (1982). "Sex differences in autism". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 12: 317–330. doi:10.1007/bf01538320.

- 1 2 3 Lovaas OI (1998). "Sex and bias: Reply to Boyd". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 28 (4): 343–344. doi:10.1023/a:1026020905266.