Dragon, Utah

| Dragon | |

|---|---|

| Ghost town | |

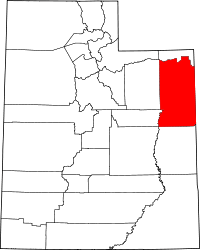

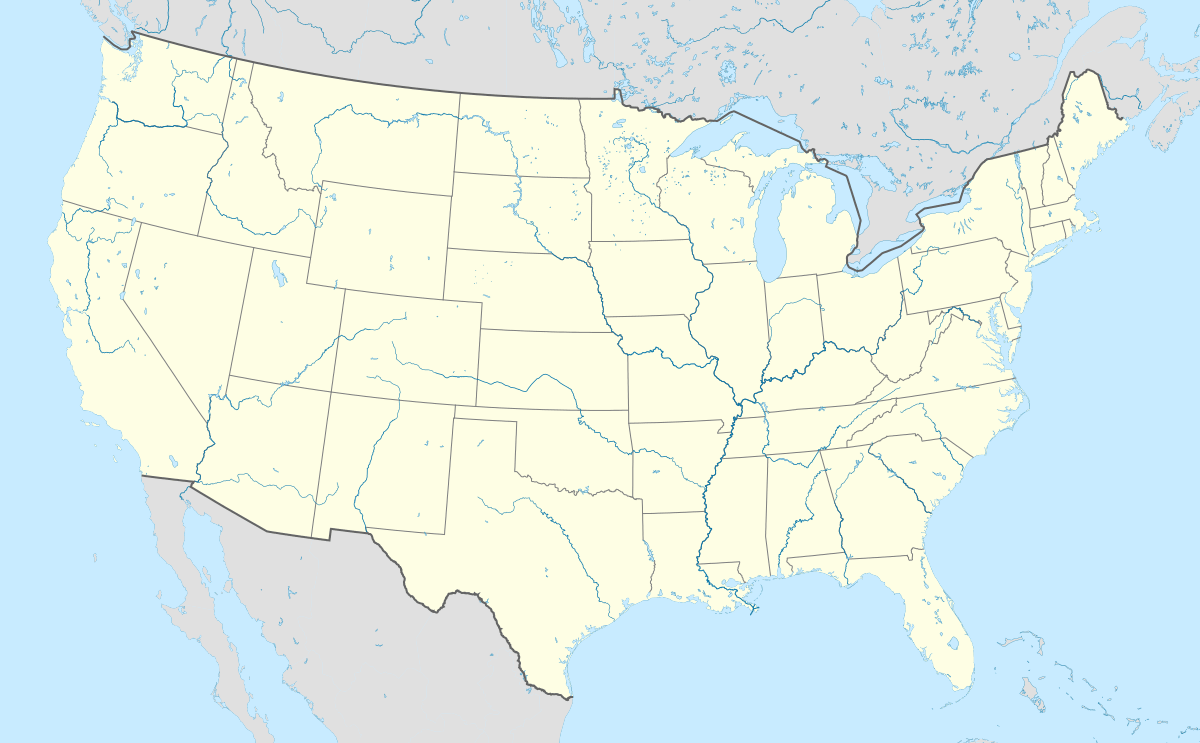

Dragon  Dragon Location of Dragon in Utah | |

| Coordinates: 39°47′09″N 109°04′24″W / 39.78583°N 109.07333°WCoordinates: 39°47′09″N 109°04′24″W / 39.78583°N 109.07333°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Utah |

| County | Uintah |

| Established | 1888 |

| Abandoned | c. 1940 |

| Named for | Black Dragon Mine |

| Elevation[1] | 5,771 ft (1,759 m) |

| GNIS feature ID | 1437547[1] |

Dragon is a ghost town located in Uintah County, at the extreme eastern edge of Utah, United States. Founded in about 1888 as a Gilsonite mining camp, Dragon boomed in the first decade of the 20th century as the end-of-line town for the Uintah Railway. Although it declined when the terminus moved farther north in 1911, Dragon survived as the largest of the Gilsonite towns. It was abandoned after its mining operations stopped in 1938 and the Uintah Railway went out of business in 1939.

Geography

Dragon lies on the tiny Evacuation Creek at the mouth of Dragon Canyon, approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) west of the Colorado state line[2] and 65 miles (105 km) southeast of Vernal, the area's main city. This part of the Uinta Basin has been isolated and barren throughout modern times. The reason for the town's existence was the veins of natural asphalt called Gilsonite, found nowhere else in the world, that run southeast to northwest through this region.[3] The present-day center of Gilsonite mining, Bonanza, is about 25 miles (40 km) to the north of Dragon.

History

As the commercial mining of Gilsonite began in 1888, a significant deposit was discovered some 1.5 miles (2.4 km) up Dragon Canyon. Observers said that the vein of the black substance formed the shape of a dragon along the surface of the ground, and the operation was named the Black Dragon Mine.[2] The name Dragon was soon given to both the canyon and the mining camp that grew up in the flat area at the canyon's mouth.[3]

The mine and town developed slowly at first, because of the difficulty of transporting the Gilsonite out of the area. The town received its first telegraph line, to Fort Duchesne, in 1901.[4]:213 In 1902, subsidiaries of the Gilson Asphaltum Company took over the Black Dragon Mine and began work on a narrow gauge railway to serve the mine. In 1904 the Uintah Railway reached Dragon, where it stopped. The company also built toll roads to Vernal and Fort Duchesne, ferries on the Green River, and a toll bridge over the White River at Ignatio, making Dragon the regional transportation hub.[4]:202–203

As the terminal station on the only railroad ever to enter the Uinta Basin, Dragon began to boom. At the completion of the railroad, the town had a depot, warehouse, locomotive shops, store, boarding house, homes, two saloons, and a barber shop.[3] The railroad company built the Uintah Railway Hotel in Dragon to lodge passengers.[4]:218 A school was established in 1904.[4]:257

Gilsonite is a flammable hydrocarbon mixture, and Dragon experienced a number of mining accidents. In 1908, a fire started in one section of Dragon's Gilsonite vein. A nearly inextinguishable fire similar to a coal seam fire, it was still burning two years later.[3] Also in 1908, an explosion in the Black Dragon Mine killed two miners.[4]:98 In 1910, a costly fire sparked in stored Gilsonite completely destroyed the Uintah Railway warehouse, along with hundreds of tons of freight.[3]

In 1910 a public library was established in Dragon, with an unusual arrangement. The Uintah Railway would transport library books free of charge to and from any borrower along its route.[3]

At the 1910 census, the population of "Dragon Precinct" (the town and surrounding area) was 287.[5] The output of the Black Dragon Mine was declining, however, and other rich Gilsonite deposits had been discovered to the north. In 1911 the Uintah Railway extended its line northward, establishing a new end-of-line town called Watson 9.5 miles (15.3 km) north of Dragon, with a spur line 4 miles (6.4 km) to the southwest of Watson to Rainbow, the new mining center. The loss of the railroad terminus caused a moderate decline in Dragon,[3] but because the railroad's shops and roundhouse were still here, Dragon remained the stable population center in the Gilsonite mining area.[2] The railroad saw the need to encourage the shipping of diverse products, and in 1912 they built large sheep shearing pens at Dragon.[4]:111 Enough people remained in 1917 to support a renovation of the Dragon schoolhouse.[3] The census precinct, greatly expanded but still named for Dragon, reported populations of 487 in 1920 and 452 in 1930.[5]

By 1938, all of the Gilsonite mining activity moved still further north, to the Bonanza area. The Dragon and Rainbow mines closed down. Trucks to Vernal and Craig, Colorado replaced trains for hauling Gilsonite. People started to abandon Dragon, Rainbow, and Watson. In 1939 Dragon's population was just 72, mostly railroad workers. Having lost the majority of its freight business, the Uintah Railway ceased operation in 1939.[3] The 1940 census recorded a "South Dragon precinct" population of 10.[5]

Only ruins remain at the Dragon site. There is a rubble pile where the hotel stood, a sidewalk that ran to the old schoolhouse, some foundations, and a small cemetery.[2][6]

References

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Dragon

- 1 2 3 4 Thompson, George A. (November 1982). Some Dreams Die: Utah's Ghost Towns and Lost Treasures. Salt Lake City: Dream Garden Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 0-942688-01-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Carr, Stephen L. (1986) [June 1972]. The Historical Guide to Utah Ghost Towns (3rd ed.). Salt Lake City: Western Epics. pp. 64–65. ISBN 0-914740-30-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Burton, Doris Karren (January 1996). A History of Uintah County: Scratching the Surface (PDF). Utah Centennial County History Series. Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society. ISBN 0-913738-06-9. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Census of Population and Housing". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- ↑ "Cemetery Database". Utah State History. Utah Department of Community and Culture. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

External links

- Dragon at GhostTowns.com