Edmund Hillary

| Sir Edmund Hillary KG ONZ KBE | |

|---|---|

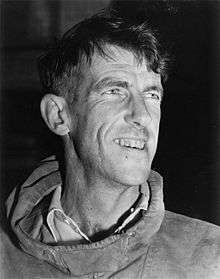

Hillary, c. 1953 | |

| Born |

Edmund Percival Hillary 20 July 1919 Auckland, New Zealand |

| Died |

11 January 2008 (aged 88) Auckland, New Zealand |

| Spouse(s) |

Louise Mary Rose (1953–1975); her death June Mulgrew (1989–2008); his death |

| Children |

Peter (b. 1954) Sarah (b. 1956) Belinda (1959–1975) |

| Parent(s) |

Percival Augustus Hillary Gertrude Hillary, née Clark |

| Awards |

Knight of the Order of the Garter Member of the Order of New Zealand Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire |

| Signature | |

| |

Sir Edmund Percival "Ed" Hillary KG ONZ KBE (20 July 1919 – 11 January 2008) was a New Zealand mountaineer, explorer, and philanthropist. On 29 May 1953, Hillary and Nepalese Sherpa mountaineer Tenzing Norgay became the first climbers confirmed to have reached the summit of Mount Everest. They were part of the ninth British expedition to Everest, led by John Hunt. TIME magazine named Hillary one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century.

Hillary became interested in mountaineering while in secondary school. He made his first major climb in 1939, reaching the summit of Mount Ollivier. He served in the Royal New Zealand Air Force as a navigator during World War II. Prior to the 1953 Everest expedition, Hillary had been part of the British reconnaissance expedition to the mountain in 1951 as well as an unsuccessful attempt to climb Cho Oyu in 1952. As part of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition he reached the South Pole overland in 1958. He subsequently reached the North Pole, making him the first person to reach both poles and summit Everest.

Following his ascent of Everest, Hillary devoted most of his life to helping the Sherpa people of Nepal through the Himalayan Trust, which he founded. Through his efforts, many schools and hospitals were built in Nepal.

Early life

Hillary was born to Percival Augustus and Gertrude (née Clark) Hillary in Auckland, New Zealand, on 20 July 1919.[1] His family moved to Tuakau (south of Auckland) in 1920, after his father (who served at Gallipoli in the 15th North Auckland) was allocated land there.[2] Hillary's grandparents were early settlers in northern Wairoa in the mid-19th century, having emigrated from Yorkshire, England.[3]

Hillary was educated at Tuakau Primary School and then Auckland Grammar School.[2] He finished primary school two years early and at high school achieved average marks.[4]

Hillary was initially smaller than his peers there and very shy, so he took refuge in his books and daydreams of a life filled with adventure. His daily train journey to and from high school was over two hours each way, during which he regularly used the time to read. He gained confidence after he learned to box. At 16, his interest in climbing was sparked during a school trip to Mount Ruapehu. Though gangly at 6 ft 5 in (195 cm) and uncoordinated, he found that he was physically strong and had greater endurance than many of his tramping companions.[5]

He studied mathematics and science at the Auckland University College and in 1939 completed his first major climb, reaching the summit of Mount Ollivier, near Aoraki/Mount Cook in the Southern Alps.[2] With his brother Rex, Hillary became a beekeeper,[1][6] a summer occupation that allowed him to pursue climbing in the winter.[7] He joined the Radiant Living Tramping Club, where a holistic health philosophy developed by the health advocate Herbert Sutcliffe was taught. Hillary developed his love for the outdoors on tours with the club through the Waitakere Ranges.[8]

His interest in beekeeping later led Hillary to commission Michael Ayrton to cast a golden sculpture in the shape of honeycomb, in imitation of Daedalus's lost-wax process. This was placed in Hillary's New Zealand garden, where his bees took it over as a hive and "filled it with honey and their young".[9]

World War II

Upon the outbreak of World War II, Hillary applied to join the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) but withdrew the application before it was considered, because he was "harassed by [his] religious conscience".[10] In 1943, the Japanese threat in the Pacific and the arrival of conscription finally undermined his pacifist inclination; Hillary joined the RNZAF as a navigator serving in No. 6 Squadron RNZAF and then No. 5 Squadron RNZAF[11] on Catalina flying boats. In 1945, he was sent to Fiji and to the Solomon Islands, where he was badly burnt in a boat accident and repatriated to New Zealand.[10]

Expeditions

On 30 January 1948, Harry Ayres, along with Mick Sullivan, led Hillary and Ruth Adams up the south ridge of Aoraki / Mount Cook, New Zealand's highest peak.[12]

In 1951, Hillary was part of a British reconnaissance expedition to Everest led by Eric Shipton,[13] before joining the successful British attempt of 1953. In 1952, Hillary and George Lowe were part of the British team led by Eric Shipton, that attempted Cho Oyu.[14] After that attempt failed due to the lack of route from the Nepal side, Hillary and Lowe crossed the Nup La into Tibet and reached the old Camp II, on the northern side, where all the pre-war expeditions camped.[15]

1953 Everest expedition

|

|

The route to Everest was closed by Chinese-controlled Tibet, and Nepal only allowed one expedition per year. A Swiss expedition (in which Tenzing took part) had attempted to reach the summit in 1952, but was turned back from the summit by bad weather and exhaustion 800 feet (240 m) below the summit. During a 1952 trip in the Alps, Hillary discovered that he and his friend George Lowe had been invited by the Joint Himalayan Committee for the approved British 1953 attempt and immediately accepted.[17]

Shipton was named as leader but was replaced by Hunt. Hillary considered pulling out, but both Hunt and Shipton talked him into remaining. Hillary was intending to climb with Lowe, but Hunt named two teams for the assault: Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans; and Hillary and Tenzing. Hillary, therefore, made a concerted effort to forge a working friendship with Tenzing.[17]

The Hunt expedition totalled over 400 people, including 362 porters, 20 Sherpa guides, and 10,000 lbs of baggage,[18][19] and like many such expeditions, was a team effort. Lowe supervised the preparation of the Lhotse Face, a huge and steep ice face, for climbing. Hillary forged a route through the treacherous Khumbu Icefall.[17]

The expedition set up base camp in March 1953 and, working slowly, set up its final camp at the South Col at 25,900 feet (7,890 m). On 26 May, Bourdillon and Evans attempted the climb but turned back when Evans' oxygen system failed. The pair had reached the South Summit, coming within 300 vertical feet (91 m) of the summit.[19][20] Hunt then directed Hillary and Tenzing to go for the summit.[20]

Snow and wind held the pair up at the South Col for two days. They set out on 28 May with a support trio of Lowe, Alfred Gregory, and Ang Nyima. The two pitched a tent at 27,900 feet (8,500 m) on 28 May, while their support group returned down the mountain. On the following morning Hillary discovered that his boots had frozen solid outside the tent. He spent two hours warming them before he and Tenzing, wearing 30-pound (14 kg) packs, attempted the final ascent.[17] The crucial move of the last part of the ascent was the 40-foot (12 m) rock face later named the "Hillary Step". Hillary saw a means to wedge his way up a crack in the face between the rock wall and the ice, and Tenzing followed.[21] From there the following effort was relatively simple. Hillary reported that both men reached the summit at the same time, but in The Dream Comes True, Tenzing said that Hillary had taken the first step atop Mount Everest. They reached Everest's 29,028 ft (8,848 m) summit, the highest point on earth, at 11:30 am.[1][22] As Hillary put it, "A few more whacks of the ice axe in the firm snow, and we stood on top."[23]

They spent only about 15 minutes at the summit. Hillary took the famous photo of Tenzing posing with his ice-axe, but Hillary's ascent went unrecorded. BBC News attributed this to Tenzing's having never used a camera,[24][25] but according to Tenzing's autobiography, Man of Everest, when Tenzing offered to take Hillary's photograph Hillary declined: "I motioned to Hillary that I would now take his picture. But for some reason he shook his head; he did not want it", Tenzing wrote. Tenzing left chocolates in the snow as an offering, and Hillary left a cross that he had been given by John Hunt.[17] Additional photos were taken looking down the mountain, to confirm that they had made it to the top and that the ascent was not faked.[25]

The two had to take care on the descent after discovering that drifting snow had covered their tracks, complicating the task of retracing their steps. The first person they met was Lowe, who had climbed up to bring them hot soup.

Well, George, we knocked the bastard off.

News of the expedition reached Britain on the day of Queen Elizabeth II's coronation, and the press called the successful ascent a coronation gift.[26] In return, the 37 members of the party received the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal with MOUNT EVEREST EXPEDITION engraved on the rim. The group was surprised by the international acclaim they received upon arriving in Kathmandu.[17] Hillary and Hunt were knighted by the young queen,[27] while Tenzing – ineligible for knighthood as a Nepalese citizen – received the George Medal from the British Government for his efforts with the expedition.[28][29][30]

After Everest

Hillary climbed ten other peaks in the Himalayas on further visits in 1956, 1960–1961, and 1963–1965. He also reached the South Pole as part of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, for which he led the New Zealand section, on 4 January 1958. His party was the first to reach the Pole overland since Amundsen in 1911 and Scott in 1912, and the first ever to do so using motor vehicles.[31]

Hillary narrowly missed becoming a victim in TWA Flight 266 from the American midwest in the 1960 New York air disaster, having been late for his flight.[32]

In the summer of 1962, he was a guest on the television show What's My Line?. The panellists were blindfolded for his appearance. He stumped the panel, comprising Dorothy Kilgallen, guest panelist Merv Griffin, Arlene Francis, and Bennett Cerf.[33]

In 1977, he led a jetboat expedition, titled "Ocean to Sky", from the mouth of the Ganges River to its source.[34] Between 1977 and 1979, Hillary commentated aboard several Antarctic sightseeing flights operated by Air New Zealand.[35] He was scheduled to commentate on 28 November 1979 Air New Zealand Flight 901, but had to pull out due to work commitments in the United States and was replaced by his close friend Peter Mulgrew. The aircraft crashed into Mount Erebus in Antarctica, killing all 257 on board.[36] Hillary later married Mulgrew's widow.[37][38]

In 1985, he accompanied Neil Armstrong in a small twin-engined ski plane over the Arctic Ocean and landed at the North Pole. Hillary thus became the first man to stand at both poles and on the summit of Everest.[39][40][41][42]

Hillary was highly critical of a decision not to try to rescue David Sharp (an Everest climber who died on the mountain in 2006), saying that leaving other climbers to die is unacceptable, and the desire to get to the summit has become all-important. He also said, "I think the whole attitude towards climbing Mount Everest has become rather horrifying. The people just want to get to the top. It was wrong if there was a man suffering altitude problems and was huddled under a rock, just to lift your hat, say good morning and pass on by". He also told the New Zealand Herald that he was horrified by the callous attitude of today's climbers. "They don't give a damn for anybody else who may be in distress and it doesn't impress me at all that they leave someone lying under a rock to die", and that, "I think that their priority was to get to the top and the welfare of ... a member of an expedition was very secondary."[43]

Australian mountaineer Adam Darragh, in turn, considered Hillary's criticism of expedition leader Russell Brice and his team as too harsh.[44] Mark Inglis, while maintaining that he remained on good terms with Hillary after the incident,[45] noted that Sharp was "almost frozen solid" and "effectively dead" when the team found him in the difficult terrain on their descent.[46]

In January 2007, Hillary travelled to Antarctica to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of Scott Base. He flew to the station on 18 January 2007 with a delegation including the Prime Minister.[47][48][49] While there he called for the British government to contribute to the upkeep of Robert Falcon Scott's and Ernest Shackleton's huts.[50]

On 22 April 2007, while on a trip to Kathmandu, Hillary was reported to have suffered a fall. There was no comment on the nature of his illness, and he did not immediately seek treatment. He was hospitalised after returning to New Zealand.[51]

Public recognition

On 6 June 1953 Hillary was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire and received the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal the same year;[27] and on 6 February 1987 was the fourth appointee to the Order of New Zealand.[52] On 22 April 1995 Hillary was appointed Knight Companion of The Most Noble Order of the Garter.[53][54] The Government of India conferred on him its second highest civilian award, the Padma Vibhushan, posthumously, in 2008.[55] He was also awarded the Polar Medal in 1958 for his part in the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition,[56][57] and the Order of Gorkha Dakshina Bahu, 1st Class of the Kingdom of Nepal in 1953 and the Coronation Medal in 1975.[58] His favoured New Zealand charity was the Sir Edmund Hillary Outdoor Pursuits Centre Inc. (OPC) of which he was Patron for 35 years. Hillary was particularly keen on the work this organisation did in introducing young New Zealanders to the outdoors in a very similar way to his first experience of a school trip to Mt Ruapehu at the age of 16. Various streets, schools and organisations around New Zealand and abroad are named after him. A few examples are Hillary College (Otara), Edmund Hillary Primary School (Papakura) and the Hillary Commission (now SPARC). Several schools have houses named after him, including Auckland Grammar School, Edgecumbe College, Hutt International Boys' School, Macleans College, Rangiora High School, Tauranga Boys' College, Upper Hutt College, Sacred Heart RC Primary School, Anglican Church Grammar School, Hornsby House School, and Endeavour Primary School.

In 1992 Hillary appeared on the updated New Zealand $5 note, thus making him the only New Zealander to appear on a banknote during his or her lifetime, in defiance of the established convention for banknotes of using only depictions of deceased individuals, and current heads of state. The Reserve Bank governor at the time, Don Brash, had originally intended to use a deceased sportsperson on the $5 note but could not find a suitable candidate. Instead he broke with convention by requesting and receiving Hillary's permission – along with an insistence from Hillary to use Aoraki/Mount Cook rather than Mount Everest in the backdrop. The image also features a Ferguson TE20 tractor like the one Hillary used to reach the South Pole on the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition. A 2.3-metre (7.5 ft) bronze statue of "Sir Ed" is installed outside The Hermitage Hotel at Mount Cook Village; it was unveiled by Hillary himself in 2003.[60]

On 17 June 2004 Hillary was awarded Commander's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland.[61]

To mark the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the first successful ascent of Everest the Nepalese government conferred honorary citizenship upon Hillary at a special Golden Jubilee celebration in Kathmandu, Nepal. He was the first foreign national to receive that honour.[62]

In 2005 a poll conducted by Reader's Digest put Hillary as "New Zealand's most trusted individual", beating cyclist Sarah Ulmer and film director Peter Jackson.[63] He kept the title in 2006 and 2007[64] After his death in 2008 he was succeeded by Willie Apiata VC, a Corporal in the NZSAS.[65]

Two Antarctic features are named after Hillary. The Hillary Coast is a section of coastline south of Ross Island and north of the Shackleton Coast. It is formally recognised by New Zealand, the United States of America and Russia. The Hillary Canyon, an undersea feature in the Ross Sea appears on the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans, which is published by the International Hydrographic Organization.[66]

Personal life

Hillary married Louise Mary Rose on 3 September 1953, soon after the ascent of Everest. A shy man, he relied on his future mother-in-law to propose on his behalf.[6][7][67] They had three children: Peter (born 1954), Sarah (born 1955) and Belinda (1959–1975).[1][20] In 1975 while en route to join Hillary in the village of Phaphlu, where he was helping to build a hospital, Louise and Belinda were killed in a plane crash near Kathmandu airport shortly after take-off.[6] In 1989 he married June Mulgrew, the widow of his close friend Peter Mulgrew, who died having replaced Hillary as speaker on Air New Zealand Flight 901, a sightseeing flight to the Antarctic which crashed into Mount Erebus in 1979.[7][68] His son Peter Hillary has also become a climber, summiting Everest in 1990. In May 2002 Peter climbed Everest as part of a 50th anniversary celebration; Jamling Tenzing Norgay (son of Tenzing; Tenzing himself had died in 1986) was also part of the expedition.[69] Hillary is also survived by six grandchildren.[70]

He spent most of his life (when not away on expeditions) living in a property on Remuera Road in Auckland City,[71] where he enjoyed reading adventure and science fiction novels in his retirement.[71]

Hillary also built a bach at Whites Beach,[72] one of Auckland's west coast beaches in the former Waitakere City, between Anawhata and North Piha.[73][74] Bob Harvey, mayor of Waitakere,[75] and friend of Hillary from the early 1970s,[72] said that "the West Coast was Sir Ed's second home. Anawhata was his favourite beach; a place he called the most beautiful on the planet."[76] Harvey said that the bach was Hillary's place of solace, where he would go when the media attention became too much – including after his return from conquering Everest.[72] "Building the cottage at Whites Beach – he told me – was one of his greatest pleasures." Aside from the bach, Hillary also co-owned a large piece of land in Karekare Valley in the 1970s with fellow climber Mike Gill.[72]

The Hillary family has had a connection with the West Coast of Auckland since 1925, when Hillary's father-in-law, Jim Rose, built a bach at Anawhata.[77] The family donated land at Whites Beach that is now crossed by trampers on the Hillary Trail, named for Edmund (see Tributes, below).[76]

That is the thing that international travel brings home to me – it's always good to be going home.This is the only place I want to live in; this is the place I want to see out my days.

— Edmund Hillary, speaking about Auckland's West Coast[78]

Philanthropy

Following his ascent of Everest he devoted much of his life to helping the Sherpa people of Nepal through the Himalayan Trust, which he founded in 1960[79] and led until his death in 2008. Through his efforts many schools and hospitals were built in this remote region of the Himalayas. He was the Honorary President of the American Himalayan Foundation, a United States non-profit body that helps improve the ecology and living conditions in the Himalayas. He was also the Honorary President of Mountain Wilderness, an international NGO dedicated to the worldwide protection of mountains.[80]

Political involvement

Hillary took part in the 1975 New Zealand general election, as a member of the "Citizens for Rowling" campaign. His involvement in this campaign was seen as precluding his nomination as Governor-General,[81] which position was instead offered to Keith Holyoake in 1977. However, in 1985, Hillary was appointed New Zealand High Commissioner to India (concurrently High Commissioner to Bangladesh and Ambassador to Nepal) and spent four and a half years based in New Delhi.[82]

As at 1975, Hillary served as a Vice President for the Abortion Law Reform Association of New Zealand. The Association is New Zealand's national pro-choice advocacy group which was founded in 1971.[83] As at 1978, he was a patron of REPEAL, a New Zealand-wide organisation that sought to repeal the restrictive Contraception, Sterilisation, and Abortion Act 1977. The organization collected 319,000 signatures for a petition that demanded the law be overturned.[84]

Death

On 11 January 2008, Hillary died of heart failure at the Auckland City Hospital at the age of 88.[85] Hillary's death was announced by New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark at around 11:20 am. She stated that his death was a "profound loss to New Zealand".[86] His death was recognised by the lowering of flags to half-mast on all Government and public buildings and at Scott Base in Antarctica.[87] Actor and adventurer Brian Blessed, who attempted to climb Everest three times, described Sir Edmund as a "kind of titan". He was in hospital at the time of his death but was expected to come home that day according to his family.[5][88][89][90][91][92]

After Hillary's death the Green Party proposed a new public holiday for 20 July or the Monday nearest to it.[93] Renaming mountains after Hillary was also proposed. The Mt Cook Village's Hermitage Hotel, the Sir Edmund Hillary Alpine Centre and Alpine Guides, proposed a renaming of Mount Ollivier, the first mountain climbed by Hillary. The family of Arthur Ollivier, for whom the mountain is named, are against such a renaming.[94]

Funeral

A state funeral was held for Hillary on 22 January 2008,[95] after which his body was cremated. The first part of this funeral was on 21 January when Hillary's casket was taken into Holy Trinity Cathedral to lie in state.[96] On 29 February 2008, in a private ceremony, most of Hillary's ashes were scattered in Auckland's Hauraki Gulf as he had desired.[97] The remainder went to a Nepalese monastery near Everest; a plan to scatter them on the summit was cancelled in 2010.[98]

On 2 April 2008, a service of thanksgiving was held in his honour at St George's Chapel in Windsor Castle. It was attended by the Queen (but not the Duke of Edinburgh owing to a chest infection) and New Zealand dignitaries including Prime Minister Helen Clark. Sir Edmund's family and family members of Tenzing Norgay attended as well. Gurkha soldiers from Nepal, a country Sir Edmund Hillary held much affection for, stood guard outside the ceremony.[99][100]

On 5 November 2008, a commemorative set of five stamps was issued.[101]

Tributes

There have been many calls for lasting tributes to Sir Edmund Hillary. The first major public tribute has been by way of the "Summits for Ed" tribute tour organised by the Sir Edmund Hillary foundation.[102] This tribute tour went from Bluff at the bottom of the South Island to Cape Reinga at the tip of the North Island, visiting 39 towns and cities along the way. In each venue school children and members of the public were invited to join together to climb a significant hill or site in their area to show their respect for Hillary. Public were also invited to bring small rocks or pebbles that had special significance to them, that would be collected and included in a memorial to Hillary at the base of Mt Ruapehu in the grounds of the Sir Edmund Hillary Outdoor Pursuits Centre. Any funds donated during the tour are to be used by the foundation to sponsor young New Zealanders on outdoor courses to continue the values that Hillary espoused. Over 8,000 members of the public attended these "Summit" climbs between March and May 2008.[103]

In January 2008, Lukla Airport, in Lukla, Nepal, was renamed to Tenzing-Hillary Airport in honour of Sir Edmund and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, for their efforts in the construction of the airport.[104]

On 23 October 2008, it was announced that all future England vs New Zealand rugby test matches will be played for the Hillary Shield named in honour of Sir Edmund. The shield was contested for the first time on 29 November 2008 at Twickenham Stadium, and was presented to the winning team, the New Zealand national rugby union team, by Lady Hillary.[105] Also on 23 October 2008 the Duke of Edinburgh's Award in New Zealand (formerly the Young New Zealanders' Challenge) was announced as the youth programme that would take Sir Edmund's name as part of its brand (at the request of the NZ Govt and the Hillary family). The organisation re-branded on 20 August 2009 as "The Duke of Edinburgh's Hillary Award".[106]

On 11 January 2009 at 9 am the New Zealand duo, "The Kiwis", performed their tribute song "Hillary 88" in front of the Beehive in Wellington. This has been recorded as the official world memorial song for Sir Edmund Hillary with the endorsement of Lady Hillary. The band members were Dean Ward and George Watson of Levin.[107]

A four-day track in the Waitakere Ranges, along Auckland's west coast, is named the Hillary Trail,[108] in honour of Sir Edmund.[76] Hillary's father-in-law, Jim Rose, who had built a bach at Anawhata in 1925, wrote "My family look forward to the time when we will be able to walk from Huia to Muriwai on public walking tracks like the old-time Maori could do" in his 1982 history of Anawhata Beach.[77][109] Hillary loved the area, and had his own bach near Anawhata (see Personal life, above). He and his friend, former mayor Bob Harvey,[72] kept Rose's dream alive,[109] and the track was eventually opened on 11 January 2010, the second anniversary of Hillary's death.[85][110] Rose Track, descending from Anawhata Road to Whites Beach, is named after the Rose family.[78][111]

The South Ridge of Aoraki/Mount Cook, New Zealand's highest mountain, was renamed Hillary Ridge on 18 August 2011. Hillary and three other climbers were the first party to successfully climb the ridge in 1948.[112] In September 2013 the Government of Nepal proposed naming a 7,681 metres (25,200 ft) mountain in Nepal Hillary Peak in his honour.[113] After the New Horizons mission discovered a mountain range on Pluto on 14 July 2015, it was informally named Hillary Montes (Hillary Mountains) by NASA.[114]

Legacy

- A bronze bust of Hillary (circa 1953) by Ophelia Gordon Bell is in the Te Papa museum in Wellington, New Zealand.[115]

- Hillary Montes, the second-highest mountain range on Pluto, is named in honor of Edmund Hillary.

- The Sir Edmund Hillary Archive was added to the UNESCO Memory of the world archive in 2013,[116] it is currently held by the Auckland War Memorial Museum[117]

Arms

|

|

Publications

Books written by Hillary include:

- High Adventure (1955), Hodder & Stoughton (London) (reprinted Oxford University Press (paperback) ISBN 1-932302-02-6 and as High Adventure: The True Story of the First Ascent of Everest ISBN 0-19-516734-1)

- East of Everest — An Account of the New Zealand Alpine Club Himalayan Expedition to the Barun Valley in 1954, with George Lowe (1956), E. P. Dutton and Company, Inc. ASIN B000EW84UM

- No Latitude for Error (1961), Hodder & Stoughton. ASIN B000H6UVP6.

- The New Zealand Antarctic Expedition (1959), R.W. Stiles, printers. ASIN B0007K6D72.

- The Crossing of Antarctica; the Commonwealth Transantarctic Expedition, 1955–1958 with Sir Vivian Fuchs (1958). Cassell ASIN B000HJGZ08

- High in the thin cold air; the story of the Himalayan Expedition, led by Sir Edmund Hillary, sponsored by World Book Encyclopedia, with Desmond Doig (1963) ASIN B00005W121

- Schoolhouse in the Clouds (1965); ASIN B00005WRBB

- Nothing Venture, Nothing Win (1975) Hodder & Stoughton General Division; ISBN 0-340-21296-9

- From the Ocean to the Sky: Jet Boating Up the Ganges Ulverscroft Large Print Books Ltd (November 1980); ISBN 0-7089-0587-0

- Two Generations with Peter Hillary (1984) Hodder & Stoughton Ltd; ISBN 0-340-35420-8

- Ascent: Two Lives Explored: The Autobiographies of Sir Edmund and Peter Hillary (1992) Paragon House Publishers ISBN 1-55778-408-6

- View from the Summit: The Remarkable Memoir by the First Person to Conquer Everest (2000) Pocket; ISBN 0-7434-0067-4

Further reading

- Johnston, Alexa (2013). Sir Edmund Hillary: An Extraordinary Life. Penguin Random House New Zealand Limited. p. 504. ISBN 978-0143006466.

- Little, Paul (2012). After Everest: Inside the private world of Edmund Hillary. Sydney, Australia: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-877505-20-1.

- Tuckey, Harriet (2013). Everest: The First Ascent — How a Champion of Science Helped to Conquer the Mountain. Lyons Press. p. 424. ISBN 978-0762791927.

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Famous New Zealanders". Christchurch City Libraries. Retrieved 23 January 2007.

- 1 2 3 Ministry for Culture and Heritage (11 January 2008). "The early years – Ed Hillary". New Zealand History online – Nga korero aipurangi o Aotearoa. Wellington, New Zealand. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- ↑ Tyler, Heather (8 October 2005). "Authorised Hillary biography reveals private touches". The New Zealand Herald. NZPA. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Robinson, Simon (10 January 2008). "Sir Edmund Hillary: Top of the World". TIME Magazine. Retrieved 14 January 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Hillary mourned, both in Nepal and New Zealand". Timesonline.co.uk. 11 January 2008. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- 1 2 3 Robert Sullivan, Time Magazine, Sir Edmund Hillary—A visit with the world's greatest living adventurer, 12 September 2003. Retrieved 22 January 2007. Archived 25 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 National Geographic, Everest: 50 Years and Counting. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ↑ Barnett, Shaun (30 October 2012). "Hillary, Edmund Percival – Early mountaineering". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ↑ Davenport, Guy (1981). The Geography of the Imagination. North Point Press. p. 59.

- 1 2 Calder, Peter (11 January 2008). "Sir Edmund Hillary's life". The New Zealand Herald. APN Holdings NZ Limited. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- ↑ "Edmund Percival Hillary". Auckland War Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ↑ Langton, Graham (22 June 2007). "Ayres, Horace Henry 1912–1987". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ↑ Isserman, Maurice; Weaver, Stewart (2008). Fallen Giants : A History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ↑ Barnett, Shaun (7 December 2010). "Cho Oyu expedition team, 1952". The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography.

- ↑ Gordon, Harry (12 January 2008). "Hillary, deity of the high country", The Australian. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ "Sir Edmund Hillary scales the heights of literary society". WNYC. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Edmund, Hillary. High Adventure: The True Story of the First Ascent of Everest.

- ↑ Hillary of New Zealand and Tenzing reach the top, Reuter (in The Guardian, 2 June 1953)

- 1 2 Reaching The Top Archived 16 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Royal Geographical Society. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- 1 2 3 The New Zealand Edge, Sir Edmund Hillary—King Of The World. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ↑ Ascent: Two Lives Explored : The Autobiographies of Sir Edmund and Peter Hillary.

- ↑ Everest not as tall as thought Agençe France-Presse (on abc.net.au), 10 October 2005

- ↑ PBS, NOVA, First to Summit, Updated November 2000. Retrieved 31 March 2007.

- ↑ Obituary: Sir Edmund Hillary BBC News, 11 January 2008

- 1 2 Joanna Wright (2003). "The Photographs Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.", in Everest, Summit of Achievement, by the Royal Geographic Society. Simon & Schuster, New York. ISBN 0-7432-4386-2. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- ↑ Reuters (2 June 1953), "2 of British Team Conquer Everest", New York Times, p. 1, retrieved 18 December 2009

- 1 2 The London Gazette: no. 39886. p. 3273. 12 June 1953. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- ↑ 'George Medal for Tensing – Award Approved by the Queen' in The Times (London), issue 52663 dated Thursday 2 July 1953, p. 6

- ↑ Hansen, Peter H. (2004). "'Tenzing Norgay [Sherpa Tenzing] (1914–1986)'" ((subscription required)). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ↑ Vallely, Paul (10 May 1986). "Man of the mountains Tenzing dies". The Times. UK.

- ↑ Ministry for Culture and Heritage (22 July 2014). "Edmund Hillary in Antarctica". New Zealand History online – Nga korero aipurangi o Aotearoa. Wellington, New Zealand. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ Barron, James, "Park Slope Plane Crash | A Collision in the Clouds", nytimes.com, 12 December 2010; retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ↑ "What's My Line?: EPISODE No.614". tv.com. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ↑ Ministry for Culture and Heritage (13 January 2016). "The end of the 'big mountain days' – Ed Hillary".". New Zealand History online – Nga korero aipurangi o Aotearoa. Wellington, New Zealand. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ The Antarctic experience – Erebus disaster New Zealand History online; retrieved 13 January 2008.

- ↑ Radio New Zealand, Sir Edmund Hillary: A Tribute. Retrieved 14 January 2008. Archived 12 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ On top of the world: Ed Hillary – Full biography of Hillary on NZHistory.net.nz

- ↑ NZEdge biography, nzedge.com; accessed 26 July 2015.

- ↑ Attwooll, Jolyon. "Sixty fascinating Everest facts". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ↑ TIME: The Greatest Adventures of All Time – The Race to the Pole (interview with Sir Edmund) Archived 25 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ March 2003 interview with Hillary in The Guardian

- ↑ "Video: Interview on HardTalk". BBC News. 11 January 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ McKinlay, Tom (24 May 2006). "Wrong to let climber die, says Sir Edmund". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Gregory, Angela (25 May 2006). "Inglis faces mental stress after harsh criticism". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ "Hillary's loss will be devastating to Nepal – Inglis". The New Zealand Herald. 11 January 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Cheng, Derek (25 May 2006). "Dying Everest climber was frozen solid, says Inglis". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ NDTV, Sir Edmund Hillary revisits Antarctica, 20 January 2007.

- ↑ Harvey, Claire (21 January 2007). "Claire Harvey on Ice: Mt Erebus sends chills of horror". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Radio Network, PM and Sir Edmund Hillary off to Scott Base, 15 January 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2007. Archived 26 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Hillary slates Brits over historic huts". The Press. Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- ↑ Dye, Stuart (24 April 2007). "Clark sends goodwill message to Sir Edmund". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ "The Order of New Zealand" (12 February 1987) 20 New Zealand Gazette 705 at 709.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 54017. p. 6023. 25 April 1995. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- ↑ "The Most Noble Order of the Garter-K.G." (4 May 1995) 42 1071 at 1088.

- ↑ "Pranab, Tendulkar, Asha Bhosle receive Padma Vibhushan". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 6 May 2008.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 41384. p. 2997. 13 May 1958. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- ↑ "medal, award". Auckland War Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ↑ O'Shea, Phillip. "The orders, decorations and medals of Sir Edmund Hillary, KG, ON Z, KBE (1919–2008)" (PDF). Reserve Bank Museum. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ↑ Explaining Currency NZ Government

- ↑ "Sir Edmund Hillary at The Hermitage July 2003". www.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Zmarł Edmund Hillary, pierwszy zdobywca Mt Everest". Gazeta.pl Wiadomości (in Polish). Agora S.A. 10 January 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ Mountaineering Great Edmund Hillary passes away 12 January 2008 The Rising Nepal Archived 4 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Sir Ed tops NZ's most trusted list". Television New Zealand. 30 June 2005. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ↑ Rowan, Juliet (29 May 2007). "Parents trust firefighters, but want kids to be high-earning lawyers". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ↑ "VC winner most trusted Kiwi – magazine". New Zealand Press Association. Stuff.co.nz. 21 June 2008. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ↑ Booker, Jarrod (16 January 2008). "Hillary's first mountain could take name". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 26 August 2008.

- ↑ Famous New Zealanders. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ↑ Sailing Source, Sir Edmund Hillary to Start Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ↑ National Geographic 50th Anniversary Everest Expedition Reaches Summit, National Geographic News, 25 May 2002. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ "Sir Edmund Hillary". The Edmund Hillary Foundation. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- 1 2 Sarney, Estelle (28 February 2009). "Sir Ed's haven on the market". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Sir Ed's bach a place of solace". Nor-west News. Huapai, New Zealand: Fairfax New Zealand. January 2008. OCLC 276732793. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ↑ BA30 – Helensville (Map). 1:50,000. Topo50. Land Information New Zealand. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ↑ Map 3.5 (C) Outstanding Coastal Areas (PDF) (Map). Policy Section Maps. Waitakere City Council. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ↑ Choe, Kim (8 October 2010). "Bob Harvey set to hang up mayoral chains". 3 News. Auckland, New Zealand: MediaWorks. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Multi-day Waitakere trail named after Sir Edmund Hillary" (Press release). Auckland Regional Council. 29 September 2009. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- 1 2 "Hillary Trail: The Hillary connection". Parks: Things to do. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland Regional Council. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- 1 2 Dye, Stuart (14 January 2008). "Lonely site legend's special place". The New Zealand Herald. Auckland, New Zealand: Wilson and Horton. ISSN 1170-0777. OCLC 55942740. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ "Himalayan Trust New Zealand".

- ↑ "Historical faces". Mountain Wilderness. 31 December 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Rowling: The man and the myth by John Henderson, Australia New Zealand Press, 1980.

- ↑ "Sir Edmund Hillary: Mountaineer who conquered Everest and devoted his". The Independent. 12 January 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Our History". ALRANZ.org. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "Obituaries". ALRANZ Newsletter. November 2008.

- 1 2 McKenzie-Minifie, Martha (11 January 2008). "State funeral for Sir Edmund Hillary". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Clark statement on Hillary death, cnn.com; retrieved 11 January 2008.

- ↑ "Flag flies at half-mast over a sad Scott Base". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Jim Perrin. Obituary, guardian.co.uk; accessed 26 July 2015.

- ↑ Obituary, telegraph.co.uk; 11 January 2008.

- ↑ Report, independent.co.uk; accessed 26 July 2015.

- ↑ Obituary, The Economist

- ↑ 'First man to scale Everest, Sir Edmund Hillary, dies', The Straits Times (Singapore), 12 January 2008.

- ↑ "Annual Sir Edmund Hillary Day a fitting tribute" (Press release). Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand. 14 January 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ↑ "Renaming peak for Sir Ed meets resistance". The New Zealand Herald. 18 January 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ↑ "State funeral for Sir Ed". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ "Sir Edmund Hillary lies in state". Fairfax Media. 21 January 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- ↑ "Sir Edmund Hillary takes final voyage, ashes scattered at sea". The New Zealand Herald. 29 February 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ "Sherpas cancel plan to spread Hillary ashes on Everest". BBC News. 9 April 2010. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ↑ "Sir Edmund Hillary service of thanksgiving". BBC News. 2 April 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ "Third night in hospital for duke". BBC News. 5 April 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ "Sir Edmund Hillary Stamps". New Zealand Post. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ Summits for Ed tribute tour, Sir Edmund Hillary Foundation and Outdoor Pursuits Centre.

- ↑ "Summits for Ed Tribute Tour". Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ "Nepal to name Everest airport after Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay". International Herald Tribune. 15 January 2008. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ↑ Gray, Wynne (1 December 2008). "All Blacks: Henry's men reach summit". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- ↑ "The Duke of Edinburgh's Hillary Award". Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- ↑ "Horowhenua Musicians Perform Sir Edmund Hillary's Official World Memorial Song". Horowhenua District Council. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009.

- ↑ Auckland Council http://regionalparks.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/hillary-trail. Retrieved 13 March 2016. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Wade, Pamela (13 January 2010). "Waitakere: Backyard adventure". The New Zealand Herald. Auckland, New Zealand: Wilson and Horton. ISSN 1170-0777. OCLC 55942740. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ↑ "Hillary Trail". Parks: Things to do. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland Regional Council. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ↑ "Hillary Trail Waitakere Ranges Regional Park" (PDF). Auckland Regional Council (arc). Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ Levy, Danya (10 August 2011). "Aoraki/Mt Cook ridge named after Hillary". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ↑ "Mount Everest: Hillary and Tenzing to have peaks named after them". The Guardian. 6 September 2013.

- ↑ Gipson, Lillian (25 July 2015). "New Horizons Discovers Flowing Ices on Pluto". NASA. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ↑ "Object: Sir Edmund :)Hillary". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ↑ "Sir Edmund Hillary Archive". www.unescomow.org.nz. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

- ↑ "Sir Edmund Hillary – Personal papers". Auckland War Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2015-11-22.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Edmund Hillary |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edmund Hillary. |

- On top of the world: Ed Hillary, nzhistory.net.nz

- Small but interesting part of biography

- Edmund Hillary biography from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- Videos (10) from Archives New Zealand

- Obituary of Edmund Hillary

- Interview with Sir Edmund Hillary: Mountain Climbing at Smithsonian Folkways

- Interview with Sir Edmund Hillary

- 2013: Portrait Painting of Edmund Hillary

- Edmund Hillary interview on BBC Radio 4 Desert Island Discs, 17 April 1979

- Edmund Hillary's collection is in the care of the Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

- Edmund Hillary addressing the The New York Herald Tribune Book and Author Luncheon, February 10, 1954, broadcast by WNYC.