T44 (classification)

T44 is a disability sport classification for disability athletics, applying to "Single below knee amputation or an athlete who can walk with moderately reduced function in one or both legs." It includes ISOD A4 and A9 classes.

Definition

This classification is for disability athletics.[1] This classification is one of several classifications for athletes with ambulant related disabilities. Similar classifications are T40, T42, T43, T44, T45 and T46.[2] Jane Buckley, writing for the Sporting Wheelies, describes the athletes in this classification as: "Single below knee amputation or an athlete who can walk with moderately reduced function in one or both legs."[1] The Australian Paralympic Committee defines this classification as being for athletes who have the "Single leg below knee amputation. Combined lower plus upper limb amputations. Ambulant with moderately reduced function in one or both lower limbs."[3] The International Paralympic Committee defined this class in 2011 as: "This class is for any athlete with a lower limb impairment/s that meets minimum disability criteria for: lower limb deficiency (section 4.1.4.a); impaired lower limb PROM (section 4.1.5.b); impaired lower limb muscle power (section 4.1.6.b); or leg length difference (section 4.1.7)."[4] The International Paralympic Committee defined this classification on their website in July 2016 as, "(Lower limb affected by limb deficiency, leg length difference, impaired muscle power or impaired range of movement)".[5]

-

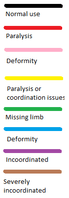

Colour guide for understanding fully body diagrams

-

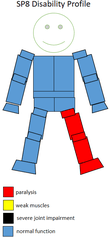

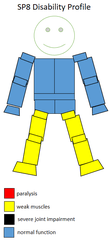

Disability type for some T44 classified competitors

Disability groups

Amputees

People who are amputees compete in this class, including ISOD A4 and A9.[6][7][8] In general, track athletes with amputations should consider track surfaces, and avoid asphalt and cinder .[7]

Lower limb amputees

This class competes in T44 and F44.[6][7][9] In modern pentathlon, they compete in P44.[10] Shank length for people in this class is not uniform, with competitors having different lengths of leg found below the knee.[10] People in this class use a three-part prosthetic limb when competing in athletics: a socket, a shank, and a foot.[7] People in this class can use standard starting blocks because their amputation generally allows for the use of a standard starting position.[7] Use of a specially made carbon fibre running prosthetic leg assists runners in this class in lowering their heart rate compared to using a prosthetic not designed for running.[11] Runners in this class can have lower metabolic costs compared to elite runners over middle and long distances.[11]

Inside the class, shank length does not impact the distance that male long jumpers can jump.[10] A study comparing the performance of athletics competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics found no significant difference in performance times between women in A3 and A4 in the javelin; women in A2, A3 and A4 in the long jump; men in the A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8 and A9 in the discus; men in A2, A3 and A4 in the discus; men in A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8 and A9 in the javelin; men in A2, A3 and A4 in the javelin; men in A2, A3 and A4 in the shot put; men in A2, A3 and A4 in the high jump; men in A4, A5 and A6 in the high jump; and men in A1, A2, A3 and A4 in the 400 meter race.[12]

Because of low participation rates in men's T43 races, the class has been combined with the T44 class. The combined class was then called T44, and included both single and double below the knee amputees. There was a push in 2008 to avoid this happening because of a perception that double below knee amputees had a competitive advantage compared to single below knee amputees.[9][13][14] Subsequent research related to results for men at the 2012 Summer Paralympics in London confirmed this to be the case for both the 200 meters and 400 meters.[9]

The nature of a person's amputations in this class can effect their physiology and sports performance.[7][15][16] Because of the potential for balance issues related to having an amputation, during weight training amputees are encouraged to use a spotter when lifting more than 15 pounds (6.8 kg).[7] Lower limb amputations effect a person's energy cost for being mobile. To keep their oxygen consumption rate similar to people without lower limb amputations, they need to walk slower.[16] People in this class use around 7% more oxygen to walk or run the same distance as someone without a lower limb amputation.[16]

People in this class can have problems with their gait. There are a number of different causes for these issues and suggested ways to modify them. For a gait that has abrupt heel contact, the cause can be excessive heel lever. This can be fixed by realigning their prosthetic foot. For jerky knee motions, the cause could be a loose socket in the knee or inadequate suspension. In that case, the socket might need replacing or they may need to realign the prosthesis. If they have prolonged heel contact, the cause could be problems with the heel lever in their prosthesis or a worn heel. Increasing heel stiffness or realigning the prosthesis corrects these issues. In some cases, prolonged heel contact or knees remaining fulling extended is a problem with training prosthesis use. Foot drag - often caused by an ill-fitting prosthesis - can be corrected by shortening the length of the prosthesis. Uneven length strides can be a result of problems with hip flexion or insecurity about their walk, both of which can be corrected by physical therapy.[15]

Upper and lower limb amputees

Members of the ISOD A9 class compete in T42, T43, T44, F42, F43, F44, F56, F57, and F58.[6][7][8] The shank length of people in this class can differ dramatically.[17] A study comparing the performance of athletics competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics found no significant difference in performance in times between men in the A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8 and A9 in the discus; men in A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8 and A9 in the javelin; and men in A8 and A9 in the shot put.[18]

The nature of an A9 athletes's amputations can effect their physiology and sports performance.[7][16][16] Because of the potential for balance issues related to having an amputation, during weight training amputees are encouraged to use a spotter when lifting more than 15 pounds (6.8 kg).[7] Lower limb amputations effect a person's energy cost for being mobile. To keep their oxygen consumption rate similar to people without lower limb amputations, they need to walk slower.[16] They are also more prone to injuries including rotator cuffs tearing, shoulder impingement, epicondylitis and peripheral nerve entrapment.[16]

Les Autres

People who are Les Autres compete in this class. This includes LAF3 and LAF5 classified athletes.[6][19] In general, Les Autres classes cover sportspeople with locomotor disabilities regardless of their diagnosis.[20][21][22][23][24][25]

LAF3

In athletics, LAF3 competitors may compete in T44. This is a standing class for people with weakness in one leg muscle or who have joint restrictions.[6] At the 1984 Summer Paralympics, LAF1, LAF2 and LAF3 track athletes had the 60 meters and 400 meter distances on the program.[6] There was a large range of sportspeople with different disabilities in this class at the 1984 Summer Paralympics.[6]

LAF3 is an Les Autres sports classification.[6][26] Sportspeople in this class use wheelchairs on a regular basis as a result of reduced muscle function. They have normal trunk functionality, balance and use of their upper limbs.[26] Medically, this class includes people with hemiparsis, and hip and knee stiffness with deformation in one arm. It means they have limited function in at least two limbs. In terms of functional classification, this means the sportsperson uses a wheelchair, has good sitting balance and has good arm function.[27] For the 1984 Summer Paralympics, LAF3 was defined by the Games organizers as, "Wheelchair bound with normal arm function and good sitting balance."[28]

LAF5

LAF5 competitors can be classified into several athletics classes including F42, F43, and F44.[6][29][30] People in this class have normal functionality in their throwing arm.[29] At the 1984 Summer Paralympics, LAF4, LAF5 and LAF6 track athletes had the 100 meters and 1,500 meters on their program. In field events, they had shot put, discus, javelin and club throws. No jumping events were on the program for these classes.[31] There was a large range of sportspeople with different disabilities in this class at the 1984 Summer Paralympics.[31] In 1997 in the United States, this class was ambulant for field events It was for people with reduced function in their lower limbs or who had balance problems. People in this class had normal function in their throwing arm.[32]

LAF5 is an Les Autres sports classification.[6][33] This is an ambulant class for people with normal upper limb functionality but who have balance issues or problems with their lower limbs.[33] Medically, this class includes people with contracture of the hip or knee, paresis of one arm, or kyphoscoliosis. In practice, this means they have limited function in at least one limb. In terms of functional classification, this means the sportsperson is ambulatory with good arm function. They have issues with balance or reduced function in their lower limbs.[27]

Spinal cord injuries

F8

F8 is standing wheelchair sport class.[34][35] The level of spinal cord injury for this class involves people who have incomplete lesions at a slightly higher level. This means they can sometimes bear weight on their legs.[36] In 2002, USA Track & Field defined this class as, "These are standing athletes with dynamic standing balance. Able to recover in standing when balance is challenged. Not more than 70 points in legs."[37] In 2003, Disabled Sports USA defined this class as, "In a sitting class but not more than 70 points in the lower limbs. Are unable to recover balance in challenged standing position."[34] In Australia, this class means combined lower plus upper limb functional problems. "Minimal disability."[38] It can also mean in Australia that the athlete is "ambulant with moderately reduced function in one or both lower limbs."[38] In Australia, the corresponding class for based on disability type classes are A2, A3, A9,and LAF5.[38]

Field events open to this class have included shot put, discus and javelin.[34][39] In pentathlon, the events for this class have included Shot, Javelin, 200m, Discus, 1500m.[34] For F8 javelin throwers, they can throw the javelin from a standing position and they use a javelin that weights .8 kilograms (1.8 lb).[40]

Performance wise, a 1999 study of discus throwers found that for F5 to F8 discus throwers, the upper arm tends to be near horizontal at the moment of release of the discus. F5 and F8 discus throwers have less average angular forearm speed than F2 and F4 throwers. F2 and F4 speed is caused by use of the elbow flexion to compensate for the shoulder flexion advantage of F5 to F8 throwers.[41] A study of javelin throwers in 2003 found that F8 throwers have angular speeds of the shoulder girdle similar to that of F3, F4, F5, F6, F7 and F9 throwers.[40]

F9

F9 is a standing wheelchair sport class used in the United States.[34][42][43] It is sometimes referred to as Standing F8.[34][43] This is a standing class for people with neurological disorders, the only one of the nine wheelchair sport classes for standing competitors.[34][42] The level of spinal cord injury for this class is largely confined to the sacral region, or involves people who have incomplete lesions at a slightly higher level. This means they can sometimes bear weight on their legs.[44] In 2003, Disabled Sports USA defined this class as, "Is a standing class but not more than 70 points in the lower limbs. Able to maintain Balance when in a challenged standing position. Internationally this class would compete in the 42,43,44 class with other ambulatory classes. Justification: Internationally there is no longer a wheelchair standing class."[34] In some competitions, F8 and F9 classes have been merged as F9, or they compete as F42, F43, or F44.[34][43]

In javelin, F9 throwers throw the javelin from a standing position and use a javelin that weighs .8 kilograms (1.8 lb).[40][45] A study of javelin throwers in 2003 found that F9 throwers have angular speeds of the shoulder girdle similar to that of F4, F5, F6, F7, F8 and F3 throwers.[40] Throwers or all types in this class use a stopboard, making them the only wheelchair class that requires the use of one.[46] In junior events in the United States, the F9 class does not participate in the pentathlon, while F3 to F8 do.[47]

Performance and rules

People in this class are not required to use a starting block. They have an option to start from a standing position, a crouch or a 3-point stance. In relay events involving T40s classes, no baton is used. Instead, a handoff takes place via touch in the exchange zone.[48] People in this class who are lower limb amputees are required to wear their leg prosthesis when they are on the track, and they must run. They cannot hop.[48]

People with arm amputations in this class can have elevated padded blocks to place their stumps on for the start of the race. These blocks need to be in a neutral color or a color similar to that of the track, and they must be placed entirely behind the starting line. Their location needs to be such that they do not interfere with the start of any other athlete.[48]

In field events for this class, athletes are not required to wear a prosthetic. In jumping events, athletes have 60 seconds during which they must complete their jump. During this time, they can adjust their prosthetic.[48]

If during a jump the athlete's prosthesis falls off and lands closer to the takeoff board than the athlete, the mark is taken where the prosthesis landed. If prosthesis lands outside the landing zone nearer the board than where athlete landed, the jump counts as a failure.[48]

Events

There are a number of events open to people in this class, often with different qualifying scores for international competitions.

| Event | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQS | BQS | AQS | BQS | |

| 100 metres | 11.75 | 12.50 | 14.20 | 15.40 |

| 200 metres | 23.30 | 25.80 | 30.50 | 33.00 |

| 400 metres | 50.80 | 53.50 | 1:20.00 | 1:30.00 |

| High jump | 1.70 | 1.50 | N/A | |

| Long jump | 5.80 | 5.20 | 4.30 | 3.80 |

| Discus throw | 46.00 | 40.00 | 22.00 | 18.00 |

| Javelin throw | 48.00 | 43.00 | N/A | |

| gender | EVENT | Class | AQS/MQS | BQS | Event |

| men's | 100m | T43/44 | 14.5 | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| women's | 100m | T43/44 | 16 | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| men's | 100m | T44 | 00:13.1 | 2016 CAIXA Loteria Athletics Open Championship | |

| women's | 100m | T44 | 00:20.0 | 2016 CAIXA Loteria Athletics Open Championship | |

| men's | 100m | T43/44 | 12.25 | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| women's | 100m | T43/44 | 15.1 | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| men's | 100m | T43/44 | 13 | 2016 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| women's | 100m | T43/44 | 16 | 2016 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | 100m | T43/44 | 12.4 | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| women's | 100m | T43/44 | 16.6 | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | 100m | T43/44 | 15.5 | 12.5 | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships |

| men's | 100m | T43/44 | 13.4 | 2015 Parapan American Games | |

| men's | 200m | T43/44 | 30 | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| women's | 200m | T43/44 | 38 | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| men's | 200m | T44 | 00:28.3 | 2016 CAIXA Loteria Athletics Open Championship | |

| women's | 200m | T44 | 00:38.0 | 2016 CAIXA Loteria Athletics Open Championship | |

| men's | 200m | T43/44 | 24.5 | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| women's | 200m | T43/44 | 31.5 | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| men's | 200m | T43/44 | 27 | 2016 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| women's | 200m | T43/44 | 33 | 2016 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | 200m | T43/44 | 26.5 | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| women's | 200m | T43/44 | 33 | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | 200m | T43/44 | 30 | 25.8 | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships |

| men's | 200m | T43/44 | 26 | 2015 Parapan American Games | |

| men's | 400m | T43/44 | 01:05.0 | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| women's | 400m | T43/44 | 01:30.0 | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| men's | 400m | T43/44 | 58 | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| women's | 400m | T43/44 | 01:20.0 | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| men's | 400m | T43/44 | 01:07.0 | 2016 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| women's | 400m | T43/44 | 01:30.0 | 2016 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | 400m | T43/44 | 01:08.0 | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| women's | 400m | T43/44 | 01:30.0 | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | 400m | T43/44 | 01:10.0 | 01:01.0 | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships |

| men's | 400m | T43/44 | 01:01.0 | 2015 Parapan American Games | |

| men's | discus | F43/44 | 30.00m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| women's | discus | F43/44 | 21.00m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| men's | discus | F44 | 34.96 | 2016 CAIXA Loteria Athletics Open Championship | |

| men's | discus | F43/44 | 44.00m | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| women's | discus | F43/44 | 22.00m | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| men's | discus | F43/44 | 33.00m | 2016 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | discus | F43/44 | 33.00m | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| women's | discus | F43/44 | 15.00m | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | discus | F43/44 | 24.00m | 40.00m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships |

| men's | discus | T43/44 | 1.50m | 1.50m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships |

| men's | discus | F43/44 | 33.00m | 2015 Parapan American Games | |

| women's | discus | F43/44 | 15.00m | 2015 Parapan American Games | |

| men's | high jump | T43/44 | 1.50m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| men's | high jump | T44 | 1.5 | 2016 CAIXA Loteria Athletics Open Championship | |

| men's | high jump | T44 | 1.65m | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| men's | high jump | T43/44 | 1.50m | 2016 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | high jump | T44 | 1.55m | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | high jump | T44 | 1.50m | 2015 Parapan American Games | |

| men's | javelin | F43/44 | 34.00m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| men's | javelin | F44 | 40 | 2016 CAIXA Loteria Athletics Open Championship | |

| men's | javelin | F43/44 | 42.00m | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| men's | javelin | F42/43/44 | 35.00m | 2016 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | javelin | F43/44 | 32.00m | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | javelin | F43/44 | 34.00m | 43.00m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships |

| men's | javelin | F43/44 | 38.00m | 2015 Parapan American Games | |

| men's | long jump | T43/44 | 5.00m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| women's | long jump | T43/44 | 3.80m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| men's | long jump | T44 | 4.6 | 2016 CAIXA Loteria Athletics Open Championship | |

| men's | long jump | T43/44 | 5.70m | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| women's | long jump | T43/44 | 4.30m | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| men's | long jump | T43/44 | 5.15m | 2016 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| women's | long jump | T43/44 | 3.60m | 2016 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | long jump | T43/44 | 5.15m | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| women's | long jump | T43/44 | 3.55m | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | long jump | T43/44 | 5.00m | 5.20m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships |

| men's | long jump | T43/44 | 5.15m | 2015 Parapan American Games | |

| men's | shot put | F43/44 | 8.40m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| women's | shot put | F43/44 | 7.00m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| men's | shot put | F44 | 11.50m | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| women's | shot put | F43/44 | 8.00m | 2015 IPC Athletics World Championships | |

| men's | shot put | F43/44 | 10.00m | 2016 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | shot put | F44 | 11.00m | 2014 IPC Athletics European Championships | |

| men's | shot put | F43/44 | 8.00m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships | |

| men's | shot put | F43/44 | 8.00m | 2016 IPC Athletics Asia-Oceania Championships |

History

The classification was created by the International Paralympic Committee and has roots in a 2003 attempt to address "the overall objective to support and co-ordinate the ongoing development of accurate, reliable, consistent and credible sport focused classification systems and their implementation."[49]

For the 2016 Summer Paralympics in Rio, the International Paralympic Committee had a zero classification at the Games policy. This policy was put into place in 2014, with the goal of avoiding last minute changes in classes that would negatively impact athlete training preparations. All competitors needed to be internationally classified with their classification status confirmed prior to the Games, with exceptions to this policy being dealt with on a case by case basis.[50] In case there was a need for classification or reclassification at the Games despite best efforts otherwise, athletics classification was scheduled for September 4 and September 5 at Olympic Stadium. For sportspeople with physical or intellectual disabilities going through classification or reclassification in Rio, their in competition observation event is their first appearance in competition at the Games.[50]

Becoming classified

For this class, classification generally has four phases. The first stage of classification is a health examination. For amputees in this class, this is often done on site at a sports training facility or competition. The second stage is observation in practice, the third stage is observation in competition and the last stage is assigning the sportsperson to a relevant class.[51] Sometimes the health examination may not be done on site because the nature of the amputation could cause not physically visible alterations to the body. This is especially true for lower limb amputees as it relates to how their limbs align with their hips and the impact this has on their spine and how their skull sits on their spine.[52] During the observation phase involving training or practice, all athletes in this class may be asked to demonstrate their skills in athletics, such as running, jumping or throwing. A determination is then made as to what classification an athlete should compete in. Classifications may be Confirmed or Review status. For athletes who do not have access to a full classification panel, Provisional classification is available; this is a temporary Review classification, considered an indication of class only, and generally used only in lower levels of competition.[53]

While some some people in this class may be ambulatory, they generally go through the classification process while using a wheelchair. This is because they often compete from a seated position.[54] Failure to do so could result in them being classified as an ambulatory class competitor.[54] For people in this class with amputations, classification is often based on the anatomical nature of the amputation.[15][55] The classification system takes several things into account when putting people into this class. These include which limbs are affected, how many limbs are affected, and how much of a limb is missing.[56][57]

Competitors

American T44 competitor April Holmes is world record holder in the Women's T44 100m event, while French competitor Marie-Amélie Le Fur holds T44 world records at 200m, 400m and 800m distances.[58] United States runner Jerome Singleton is a strong competitor in the 100m event, winning at the IPC Athletics World Championships in 2011.[59] Richard Browne currently holds the T44 100m world record after coming second to Alan Oliveira with a time of 10.75 at the Paralympic Anniversary Games in London on 28 July 2013.[60] Other notable competitors in this class include Arnu Fourie and David Prince, who hold T44 200m and 400m world records respectively. German world record holder Markus Rehm with an 8.24m long jump was the first T44 athlete who won a national able-bodied competition, in consequence causing discussions about possible advantages of prosthesis techniques.

References

- 1 2 Buckley, Jane (2011). "Understanding Classification: A Guide to the Classification Systems used in Paralympic Sports". Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ↑ "Summer Sports » Athletics". Australia: Australian Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ "Classification Information Sheet" (PDF). Sydney, Australia. 16 November 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ Tweedy, Sean (16 July 2010). "Research Report - IPC Athletics Classification Project for Physical Impairments" (PDF). Queensland, Australiaa: International Paralympic Committee. p. 42. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ "IPC Athletics Classification & Categories". www.paralympic.org. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM FOR STUDENTS WITH A DISABILITY". Queensland Sport. Queensland Sport. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Classification 101". Blaze Sports. Blaze Sports. June 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- 1 2 Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes.

- 1 2 3 Hassani, Hossein; Ghodsi, Mansi; Shadi, Mehran; Noroozi, Siamak; Dyer, Bryce (2015-06-16). "An Overview of the Running Performance of Athletes with Lower-Limb Amputation at the Paralympic Games 2004–2012". Sports. 3 (2): 103–115. doi:10.3390/sports3020103.

- 1 2 3 Nolan, Lee; Patritti, Benjamin L.; Stana, Laura; Tweedy, Sean M. (2011). "Is Increased Residual Shank Length a Competitive Advantage for Elite Transtibial Amputee Long Jumpers?" (PDF). Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 28.

- 1 2 Broad, Elizabeth (2014-02-06). Sports Nutrition for Paralympic Athletes. CRC Press. ISBN 9781466507562.

- ↑ van Eijsden-Besseling, M. D. F. (1985). "The (Non)sense of the Present-Day Classification System of Sports for the Disabled, Regarding Paralysed and Amputee Athletes" (PDF). Paraplegia. International Medical Society of Paraplegia. 23. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ Zettler, P. Is It Cheating to Use Cheetahs? The Implications of Technologically Innovative Prostheses for Sports Value and Rules; Stanford Law School: Stanford, CA, USA, 2009.

- ↑ Dyer, B. An Insight into the Acceptable Use & Assessment of Lower-Limb Running Prostheses in Disability Sport. Ph.D. Thesis, Bournemouth University, Poole, UK, 2013.

- 1 2 3 DeLisa, Joel A.; Gans, Bruce M.; Walsh, Nicholas E. (2005-01-01). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781741309.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Miller, Mark D.; Thompson, Stephen R. (2014-04-04). DeLee & Drez's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455742219.

- ↑ Nolan, Lee; Patritti, Benjamin L.; Stana, Laura; Tweedy, Sean M. (2011). "Is Increased Residual Shank Length a Competitive Advantage for Elite Transtibial Amputee Long Jumpers?" (PDF). Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 28.

- ↑ van Eijsden-Besseling, M. D. F. (1985). "The (Non)sense of the Present-Day Classification System of Sports for the Disabled, Regarding Paralysed and Amputee Athletes" (PDF). Paraplegia. International Medical Society of Paraplegia. 23. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes.

- ↑ Tweedy, S. M. (2003). The ICF and Classification in Disability Athletics. In R. Madden, S. Bricknell, C. Sykes and L. York (Ed.), ICF Australian User Guide, Version 1.0, Disability Series (pp. 82-88)Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- ↑ Albrecht, Gary L. (2005-10-07). Encyclopedia of Disability. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781452265209.

- ↑ "Paralympic classifications explained". ABC News Sport. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

- ↑ Sportbond, Nederlandse Invaliden (1985-01-01). Proceedings of the Workshop on Disabled and Sports. Nederlandse Invaliden Sportbond.

- ↑ Narvani, A. A.; Thomas, P.; Lynn, B. (2006-09-27). Key Topics in Sports Medicine. Routledge. ISBN 9781134220618.

- ↑ Hunter, Nick (2012-02-09). The Paralympics. Hachette Children's Group. ISBN 9780750270458.

- 1 2 Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes.

- 1 2 MD, Michael A. Alexander; MD, Dennis J. Matthews (2009-09-18). Pediatric Rehabilitation: Principles & Practices, Fourth Edition. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 9781935281658.

- ↑ Broekhoff, Jan (1986-06-01). The 1984 Olympic Scientific Congress proceedings: Eugene, Ore., 19-26 July 1984 : (also: OSC proceedings). Human Kinetics Publishers. ISBN 9780873220064.

- 1 2 Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes.

- ↑ International Paralympic Committee (June 2009). "IPC Athletics Classification Project for Physical Impairments: Final Report - Stage 1" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Governing Committee Reports.

- 1 2 Broekhoff, Jan (1986-06-01). The 1984 Olympic Scientific Congress proceedings: Eugene, Ore., 19-26 July 1984 : (also: OSC proceedings). Human Kinetics Publishers. ISBN 9780873220064.

- ↑ "Men & Women 800 Meter Run - Results - 1997 National Summer Games". Disabled Sports US. Disabled Sports US. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- 1 2 Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 National Governing Body for Athletics of Wheelchair Sports, USA. Chapter 2: Competition Rules for Athletics. United States: Wheelchair Sports, USA. 2003.

- ↑ Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes.

- ↑ Foster, Mikayla; Loveridge, Kyle; Turley, Cami (2013). "S P I N A L C ORD I N JURY" (PDF). Therapeutic Recreation.

- ↑ "SPECIAL SECTION ADAPTATIONS TO USA TRACK & FIELD RULES OF COMPETITION FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field. 2002.

- 1 2 3 Sydney East PSSA (2016). "Para-Athlete (AWD) entry form – NSW PSSA Track & Field". New South Wales Department of Sports. New South Wales Department of Sports.

- ↑ Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes.

- 1 2 3 4 Chow, John W.; Kuenster, Ann F.; Lim, Young-tae (2003-06-01). "Kinematic Analysis of Javelin Throw Performed by Wheelchair Athletes of Different Functional Classes". Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 2 (2): 36–46. ISSN 1303-2968. PMC 3938047

. PMID 24616609.

. PMID 24616609. - ↑ Chow, J. W., & Mindock, L. A. (1999). Discus throwing performances and medical classification of wheelchair athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise,31(9), 1272-1279. doi:10.1097/00005768-199909000-00007

- 1 2 Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes.

- 1 2 3 "OFFICIAL GUIDE & RULES OF GAMES 2006" (PDF). GAELIC ATHLETICS & CYCLE ASSOCIATION. GAELIC ATHLETICS & CYCLE ASSOCIATION. 2006.

- ↑ Foster, Mikayla; Loveridge, Kyle; Turley, Cami (2013). "S P I N A L C ORD I N JURY" (PDF). Therapeutic Recreation.

- ↑ Foster, Mikayla; Loveridge, Kyle; Turley, Cami (2013). "S P I N A L C ORD I N JURY" (PDF). Therapeutic Recreation.

- ↑ USA Track & Field (2007). "Special Section Adaptions to the USA Track & Field Rules of Competition for Individuals with Disabilities" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field.

- ↑ "National Junior Disabled Sports Championships 2004 Registration Packet" (PDF). Mesa Association of Sports for the Disabled. Mesa Association of Sports for the Disabled. 2004.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "PARALYMPIC TRACK & FIELD: Officials Training" (PDF). USOC. United States Olympic Committee. December 11, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Paralympic Classification Today". International Paralympic Committee. 22 April 2010. p. 3.

- 1 2 "Rio 2016 Classification Guide" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. International Paralympic Committee. March 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ↑ Tweedy, Sean M.; Beckman, Emma M.; Connick, Mark J. (August 2014). "Paralympic Classification: Conceptual Basis, Current Methods, and Research Update" (PDF). Paralympic Sports Medicine and Science. 6 (85). Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ Gilbert, Keith; Schantz, Otto J.; Schantz, Otto (2008-01-01). The Paralympic Games: Empowerment Or Side Show?. Meyer & Meyer Verlag. ISBN 9781841262659.

- ↑ "CLASSIFICATION Information for Athletes" (PDF). Sydney Australia: Australian Paralympic Committee. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- 1 2 Cashman, Richmard; Darcy, Simon (2008-01-01). Benchmark Games. Benchmark Games. ISBN 9781876718053.

- ↑ Pasquina, Paul F.; Cooper, Rory A. (2009-01-01). Care of the Combat Amputee. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160840777.

- ↑ Tweedy, Sean M. (2002). "Taxonomic Theory and the ICF: Foundations for a Unified Disability Athletics Classification" (PDF). ADAPTED PHYSICAL ACTIVITY QUARTERLy. 19: 220–237. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ International Sports Organization for the Disabled. (1993). Handbook. Newmarket, ON: Author. Available Federacion Espanola de Deportes de Minusvalidos Fisicos, c/- Ferraz, 16 Bajo, 28008 Madrid, Spain.

- ↑ "IPC Athletics World Records". International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ↑ Davies, Gareth A Davies (26 Jan 2011). "Jerome Singleton pips Oscar Pistorius in 100 metres T44 final at IPC Athletics World Championships". Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/0/disability-sport/23483228

.svg.png)