Gridley J. F. Bryant

| Gridley J. F. Bryant | |

|---|---|

|

Bryant in the 1850s | |

| Born |

Gridley James Fox Bryant August 29, 1816 Scituate, Massachusetts |

| Died |

June 8, 1899 (aged 82) Boston, Massachusetts |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Gridley J. F. Bryant |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Parent(s) |

Gridley Bryant (father) Maria Winship Fox (mother) |

| Buildings |

Massachusetts State House Quincy Market Old City Hall Gloucester City Hall Dartmouth Hall Hathorn Hall Shattuck Observatory |

Gridley James Fox Bryant (August 29, 1816 – June 8, 1899),[1] often referred to as G.J.F. Bryant,[2] was a Boston architect, builder, and industrial engineer. His designs "dominated the profession of architecture in [Boston] and New England",[2] spanning his career and after. He was known as one of the most influential architects in the history of New England, and designed custom houses, government buildings, churches, schoolhouses, and private residences across the United States, and was known as being popular among the Boston elite.[1] His most notable designs are foundational buildings on numerous campus across the Northeastern United States, such as on the campuses of Dartmouth College, Tufts College, Bates College, and Harvard College.[3] He has been credited as one of the first modern architects of America, and at the height of his career was the most commissioned architect in New England and the most commissioned in the history of the city of Boston.[2]

A native of Massachusetts, his early life was heavily influenced by his father's life work in construction engineering. His father, Gridley Bryant built the first commercial railroad in the United States.[4] In his early life he did not receive formal training in architecture but taught himself industrial engineering and construction analysis as well as building design. His first informal mentor was Alexander Perris, who introduced him to neoclassical design and the utilization of Second Empire architectural templates. His self-started firm, "Bryant & Associates", was one of the most selective and popular architectural firms in New England and Bryant himself designed for institutions that provided high personal value, societal value or if sufficient payment was made to him personally, oftentimes described as "ludicrously expensive".[2] He was the first architect in history to be featured on London's The Builder, a record three of his designs were featured, his constant public featuring propelled him into the public eye and earned him expensive and large commissions. He often was paired with John Hubbard Sturgis to design and create luxury housing for wealthy private townspeople.

Early life and education

Bryant was born to Maria Winship Fox and Gridley Bryant, noted railway pioneer, in Scituate, Massachusetts. In his youth he moved to Gardiner, Maine, and attended the Garrdiner Lyceum for his secondary education. He studied mathematics and engineering there before leaving joining his father's engineering office. Outside of his secondary schools studies he interned at local lithographers and artists to experiment with design and artistic manipulation.[2]

Life and architectural career

Early career

_(14779254754).jpg)

Bryant's early career started in a time in which very few architects gained prominence in his hometown of Boston, Massachusetts, and struggled to find commercial success in the profession. Due to this, formal training and education in the field of architecture was not available to him so his passion of building soon moved to him learn building design, and construction analysis at an early age all self-taught.[2] Although the American Institute of Architects was beginning to establish itself it prompted aspiring architects to practice regulated construction, and proper licensing,[2] a thought rejected by a young Bryant. Although never traveling abroad, Bryant read extensively on the architectural practices of Europe, more specifically, London, and Paris. The Second Empire archtecutreal design as exampled in the Élysée Palace, played a key role in his later designs. He began informal training with fellow Boston architect, Alexander Perris, who introduced him to neoclassical design and the utilization of Second Empire architectural templates. His training under Perris was grounded in neoclassicism, and played an important role in his first building drafts.[2] Primarily working as a student in his early days he quickly became a paid member by moving to the newly opened architectural firm of Perris' at the corner of Court and Washington streets. His first achievement was the design for the Broadway Savings Bank, South Boston, in the early 1830s.[2]

Bryant focused on unregulated architecture and decided to create a new template for the construction of at the time buildings in New England.[2] Early on in his career he faced competition from other larger firms that sought to monopolize construction of buildings and their designs in the greater Boston area for profit. As a draftsmen, he drew up minor additions and renovations to already established buildings in Boston, and initially struggled to find footing in the competitive field.[2] Aged twenty-one, and amid an economic depression he established his own architectural firm called Bryant and Associates.[2]

Rise to prominence

Bryant & associates

A common fault that was dealt to Bryant is that he valued the art form of architecture over the commercial validity of his designs which proved to be counterproductive for his budding practice. With an understanding that a client's wishes should always come first when constructing and designing for them he, "frequently persuaded a client to spend more than he might have planned, in the interests of erecting a structure with greater aesthetic value to the community."[2] Although his firm was relatively new and had start-up funds he worked and often collaborated with hundreds of draftsmen around the city. A notable trait of Bryant was due to the low level of economic validity to hire countless draftsmen to draw up buildings and their specification he wrote length and thoroughly detailed written specifications to describe how a building should be built. His firm utilized thousands of un-retained draftsmen throughout its life and contributed to the construction of unprecedented amount of building being constructed throughout the United States. However, his designs specifically were reserved for high value projects, meaning those with high personal value, societal value or if sufficient payment was made to him. Due to his firm being largely un-retained, he was able to provide guidance to his firm's operations while in other areas of the country which contributed to increased financial success. He used the lithography he learned in secondary school to promote his firms and their projects to attract clients and donors. He was one of the first people in the city of Boston to use colored advertisements to promote his work, which contributed to even more financial success.[2]

Collaborations

His firm also attracted the architectural prowess of notable architects such as Alexander Rice Esty, Edward H. Kendall, Albert Currier, Wilfred E. Mansur, Arthur Gilman and Louis P. Rogers.[2] He worked with Albert Currier to construct the Adroscoggin County Courthouse and Jail, the largest Courthouse-Jail building in Maine at the time.[2] He worked with Wilfred E. Mansur to construct Aroostook County Courthouse and Jail, the largest Courthouse complex in Maine, in 1859.[2] In 1862, he worked with Arthur Gilman to design and eventually construct Boston's city hall, Old City Hall, one of the first to be built in the French Second Empire style in the United States. In 1869 he collaborated with Louis P. Rogers to construct Gloucester City Hall.[2]

Bryant commission

Early commissions

Bryant was commissioned to produce numerous buildings on weekly basis so much so that his partaking in architectural projects in Boston was called the "Bryant Commission" speaking to its reoccurrence and widespread demand.[2] His largest and more expansive commissions were from town and state governments, in which he worked frequently with John Hubbard Sturgis, most notably on upscale and luxury projects in the 1860s. At this time Bryant was the most commissioned architect in New England and the most commission in the history of the city of Boston.[2][3] He received the vast majority commercial commissions in Boston including the Massachusetts State House, and various other projects in the city's commercial district. Although his projects required large sums of money both in commission payments and construction he often traveled to rural areas for promotional work and designed for much lower prices for instances that provided "high societal value." Most notably was the construction of Dartmouth College's main hall, and Bates College's Hathorn Hall, in which he designed and constructed it partially himself at a price so low that when all things accounted for actually cost him money to build the two projects. Larger more wealthy educational institutions payed him top dollar for he designed such as Harvard College, which asked him to give input in the construction of various administrative buildings.[2]

.jpg)

Prominent commissions

Although bricks were the main tool in the construction of buildings in Boston at the height of Bryant's work, he often opted for the use of granite for increased stability. Most notably he along with his first mentor Alexander Perris, designed and developed the now iconic Quincy Market.[2]

Boston fire of 1872

During the Great Boston fire of 1872 152 buildings he had designed 152 buildings that ended up being burned down. He was commissioned to rebuild 110 of them, validating his popularity among the people of Boston.[1]

Bryant was a leading proponent of the Boston "Granite Style", and together with Arthur Gilman devised the Back Bay's gridiron street pattern.[2]

Style and design

Bryant built many buildings that showcase neoclassical entrance design, such as Old City Hall in Boston, Massachusetts, and Rand Hall of Bates College in Lewiston, Maine.[5][6] As an industrial engineer and architect in New England, Bryant participated in the Colonial Revival architecture movement, and subsequently constructed his projects correspondence by including cornice embellished moldings, and multi-plane windows. White pillars, as a staple of neoclassical design, can be found as the entrance to many different buildings, including some residential dorms he has created.[5]

Many of his collegiate projects possess mint-green colorization on their bell towers, building caps and tips. This architectural design can be traced back to 1799 with the construction of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[7] Many of his college buildings are American Georgian buildings that were constructed with wood and clapboards, with their columns made of timber, that have been framed up, and turned on an oversized lathe.

The green caps on the buildings Bryant created, both architecturally and structurally, were designed after Independence Hall.[5] He also designed numerous buildings on campuses that featured red brick exteriors, designed in the Georgian style, they showcased red print doors, as well as darkened ridge sides. Gothic influence is seen in all of the academic buildings Bryant produced.

Death and legacy

Bryant died on June 8, 1899 in his townhouse in Boston, Massachusetts. He was survived by his wife, Louisa Bryant who he married on September 9, 1839.[1] His only known commission in the south was Thornbury, a plantation house built in the 1840s for Henry King Burgwyn, in Northampton County, North Carolina.[8] Upon his death his wife assembled all of his books and drawing in his home study and burned down his house, at the request of his will.[2]

Notable buildings

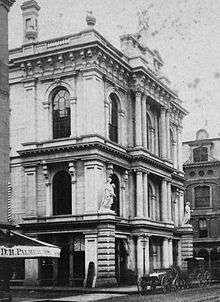

State Street Block, in Boston, Massachusetts

State Street Block, in Boston, Massachusetts.jpg) Boston Old City Hall in Boston, Massachusetts

Boston Old City Hall in Boston, Massachusetts Bigelow Chapel, Mount Auburn Cemetery in Auburn, Maine

Bigelow Chapel, Mount Auburn Cemetery in Auburn, Maine

Horticultural Hall, Tremont St., in Boston, Massachusetts

Horticultural Hall, Tremont St., in Boston, Massachusetts Gloucester City Hall, in Gloucester, Massachusetts

Gloucester City Hall, in Gloucester, Massachusetts Hathorn Hall in Lewiston, Maine

Hathorn Hall in Lewiston, Maine Shattuck Observatory in Hanover, New Hampshire

Shattuck Observatory in Hanover, New Hampshire- Dartmouth Hall in Hanover, New Hampshire

Massachusetts State House in Boston, Massachusetts

Massachusetts State House in Boston, Massachusetts- Old City Hall in Boston, Massachusetts

Listing of buildings constructed or influenced by Bryant

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gridley James Fox Bryant. |

- 1 2 3 4 Roger G. Reed, Building Victorian Boston: the architecture of Gridley J.F. Bryant (Univ of Massachusetts Press, 2007) ISBN 1-55849-555-X, 9781558495555

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 Reed, Roger (2007). Building Victorian Boston: The Architecture of Gridley J.F. Bryant. University of Massachuets. p. 16.

- 1 2 O'Gorman, James F. (2004). On the Boards: Drawings by Nineteenth-Century Boston Architects. University of Pennsylvania Library: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 57.

- ↑ White (pp.14)

- 1 2 3 Stuan, Thomas (2006). The Architecture of Bates College. Ladd Library, Bates College, Lewiston, Maine: Bates College. p. 23.

- ↑ "Hathorn Hall | Library | Bates College". www.bates.edu. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ↑ "Architecture of Independence Hall - Independence National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ↑ Robert B. MacKay and Catherine W. Bishir (2009). "North Carolina Architects & Builders: Bryant, Gridley James Fox (1816-1899)". North Carolina State University Libraries.

- ↑ Meeks, Carroll Louis Vanderslice (1956). The Railroad Station: An Architectural History. Yale University Press. p. 54. ISBN 0300007647.

- ↑ Southworth & Southworth. AIA Guide to Boston, 3rd ed. 2008

Bibliography

Cited in footnotes

- Reed, Roger. (2007) Building Victorian Boston: The Architecture of Gridley J.F. Bryant (University of Massachusetts Press); pp. 15–244

- Scholes, Robert E. (1968), The Granite Railway and its Associated Enterprises. Retrieved March 31, 2005.

- White, John H. Jr. (Spring 1986). "America's most noteworthy railroaders". Railroad History. 154: 9–15. ISSN 0090-7847. OCLC 1785797.