Cry of Dolores

| Grito de Dolores | |

|---|---|

| Observed by | Mexico |

| Date | September 16 |

| Next time | 16 September 2017 |

| Frequency | annual |

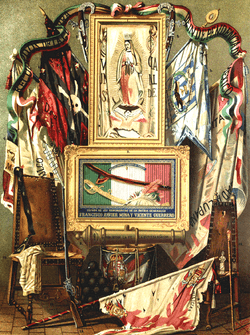

The Cry of Dolores (Spanish: Grito de Dolores) was uttered from the small town of Dolores Hidalgo, near Guanajuato in Mexico, on September 16, 1810. This event is considered the beginning of the Mexican War of Independence. The "grito" was the pronunciamiento of the Mexican War of Independence by Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a Roman Catholic priest. Since October 1825, the anniversary of the event is celebrated as Mexican Independence Day.

Event

Hidalgo and several criollos were involved in a planned revolt against the Spanish colonial government, when several plotters were killed. Fearing his arrest,[1] Hidalgo commanded his brother Mauricio, as well as Ignacio Allende and Mariano Abasolo to go with a number of other armed men to make the sheriff release the pro-independence inmates there on the early morning of September 16. They managed to set 80 free.[2] Around 2:30 a.m., on September 16, 1810, Hidalgo ordered the church bells to be rung and gathered his congregation. Flanked by Allende and Juan Aldama, he addressed the people in front of his church, urging them to revolt.

The Siege of Guanajuato, the first major engagement of the insurgency, occurred 4 days later. Mexico's independence would not be effectively declared from Spain in the Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire until September 28, 1821, after a decade of war. Former royal officer Augustín de Iturbide in alliance with insurgents including Vicente Guerrero achieved Mexican independence, but Hidalgo is credited as being the "father of his country."[3]

Wording

People celebrate this on September 16. There is no scholarly consensus as to what exactly Hidalgo said at the time, as the book The Course of Mexican History states "The exact words of this most famous of all Mexican speeches are not known, or, rather, they are reproduced in almost as many variations as there are historians to reproduce them".[4]

The book goes on to claim that "the essential spirit of the message is... 'My children: a new dispensation comes to us today. Will you receive it? Will you free yourselves? Will you recover the lands stolen three hundred years ago from your forefathers by the hated Spaniards? We must act at once... Will you defend your religion and your rights as true patriots? Long live Our Lady of Guadalupe! Death to bad government! Death to the gachupines!'"[4]

By contrast, William F. Cloud divides the sentiments above between both Hidalgo and the crowd... "He [Hidalgo] told them that the time for action on their part had now come. When he asked, 'Will you be slaves of Napoleon or will you as patriots defend your religion, your hearths and your rights?' there was a unanimous cry, 'We will defend to the utmost! Long live religion, long live our most holy mother of Guadalupe! Long live America! Death to bad government, and death to the Gachupines!'"[5]

Hidalgo’s Grito did not condemn the notion of monarchy or criticize the current social order in detail, but his opposition to the events in Spain and the current viceregal government was clearly expressed in his reference to bad government. The Grito also emphasized loyalty to the Catholic religion, a sentiment with which both Creoles and Peninsulares (native Spaniards) could sympathize; however, the strong anti-Spanish cry of “Death to Gachupines” (Gachupines was a slur given to Peninsulares) probably had caused horror among Mexico’s elite.[1]

Remembrance

This event has since assumed an almost mythic status.[6][7] Since the late 20th century, Hidalgo's "cry of independence" has become emblematic of Mexican independence.

Each year on the night of September 15, at around eleven in the evening, the President of Mexico rings the bell of the National Palace in Mexico City. After the ringing of the bell, he repeats a shout of patriotism (a Grito Mexicano) based upon the "Grito de Dolores", with the names of the important heroes of the Mexican War of Independence who were there on that very historical moment included, and ending with the threefold shout of ¡Viva México! from the balcony of the palace to the assembled crowd in the Plaza de la Constitución, or Zócalo, one of the largest public plazas in the world. After the shouting, he rings the bell again and waves the Flag of Mexico to the applause of the crowd, and is followed by the playing and mass singing of the Himno Nacional Mexicano, the national anthem, with a military band from the Mexican Armed Forces playing. This event draws up to half a million spectators from all over Mexico and tourists worldwide. On the morning of September 16, or Independence Day, the national military parade (the September 16 military parade) in honor of the holiday starts in the Zócalo and its outskirts, passes the Hidalgo Memorial and ends on the Paseo de la Reforma, Mexico City’s main boulevard, passing the El Ángel memorial column and other places along the way.

A similar celebration occurs in cities and towns all over Mexico, and in Mexican embassies and consulates worldwide on the 15th or the 16th. The mayor (or governor, in the case of state capitals and ambassadors or consuls in the case of overseas celebrations), rings a bell and gives the traditional words, with the names of Mexican independence heroes included, ending with the threefold shout of Viva Mexico!, the bell ringing for the second time, the waving of the Mexican flag and the mass singing of the National Anthem by everyone in attendance. There are also celebrations in schools as well all over the country. In the 19th century, it became common practice for Mexican presidents in their final year in office to re-enact the Grito in Dolores Hidalgo, rather than in the National Palace. President Calderón officiated at the Grito in Dolores Hidalgo as part of the bicentennial celebrations in 2010 on the 16th of September, even though he had to do this first, to launch the national bicentennial celebrations, in the National Palace balcony on the night of the 15th.[8][9] As a result, the 2012 commemoration, his last as President, was held in the National Palace balcony instead, thus becoming the third President breaking the traditional practice.

The following day, September 16 is Independence Day in Mexico and is considered a patriotic holiday, or fiesta patria (literally, Patriot Festival or Civic Festival). This day is marked by parades, patriotic programs, drum and bugle and marching band competitions, and special programs on the national and local media outlets, even concerts.[10]

Modern full version

This is the version often recited by the President of Mexico in the national commemorative activity in the National Palace or at the church in Dolores Hidalgo. For each line beginning ""¡Viva(n)!"" recited by the president, the crowd respond with "¡Viva(n)!". Local leaders can adapt this to their respective circumstances from the state to the municipal or city level, and can sometimes reverse the order while retaining the threefold Viva Mexico cry at the end.

- Spanish

- ¡Mexicanos!

- ¡Vivan los héroes que nos dieron patria!

- ¡Viva Hidalgo!

- ¡Viva Morelos!

- ¡Viva Josefa Ortíz de Dominguez!

- ¡Viva Allende!

- ¡Viva Aldama!

- ¡Viva Matamoros!

- ¡Viva la Independencia Nacional!

- ¡Viva México! ¡Viva México! ¡Viva México!

- English

- Mexicans!

- Long live the heroes who gave us our homeland!

- Long live Hidalgo!

- Long live Morelos!

- Long live Josefa Ortíz de Dominguez!

- Long live Allende!

- Long live Aldama!

- Long live Matamoros!

- Long live the nation's independence!

- Long Live Mexico! Long Live Mexico! Long Live Mexico!

References

Inline citations

- 1 2 Kirkwood, Burton (2000). History of Mexico. Westport, CT, USA: Greenwood Publishing Group, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-313-30351-7.

- ↑ Sosa, Francisco (1985) (in Spanish). Biografias de Mexicanos Distinguidos-Miguel Hidalgo. 472. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa SA. pp. 288-292. ISBN 968-452-050-6.

- ↑ Virginia Guedea, "Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 640.

- 1 2 Meyer. Michael, et al (1979): The Course of Mexican History, page 276, New York, New York USA Oxford University Press ISBN 978-0-19-502413-5

- ↑ William F. Cloud (1896). Church and State or Mexican Politics from Cortez to Diaz. Kansas City, Mo: Peck & Clark, Printers.

- ↑ Hamill, Hugh M. (1966). The Hidalgo Revolt: Prelude to Mexican Independence. University of Florida Press. ISBN 0-8130-2528-1.

- ↑ Knight, Alan (2002). Mexico: The Colonial Era. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89196-5.

- ↑ "Mexico Celebrates Its Bicentennial - Photo Gallery - LIFE". Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ↑ "Calderón revive grito original en magnos festejos por bicentenario de México" (in Spanish). Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ↑ Saint-Louis, Miya. "How to Celebrate Mexico's Independence Day: Grito de Dolores". iexplore.com. Inside-Out Media. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

General references

- Fernández Tejedo, Isabel; Nava Nava, Carmen (2001). "Images of Independence in the Nineteenth Century: The Grito de Dolores, History and Myth". In William H. Beezly and David E. Lorey. ¡Viva Mexico! ¡Viva la independencia!: Celebrations of September 16. Silhouettes: studies in history and culture series. Margarita González Aredondo and Elena Murray de Parodi (Spanish-English trans.). Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources. pp. 1–42. ISBN 0-8420-2914-1. OCLC 248568379.

- Sr. Antonio Barajas Becerra, "Entrada de los Insurgentes a la Villa de San Miguel El Grande, la tarde del Domingo, 16 de Septiembre de 1801."

- Antonio Barajas Beccera, 1969, Generalisimo don Ignacio de Allende y Unzaga, 2a edicion, p. 108 ("a las cinco de la manana del domingo 16 de Septiembre, 1810").

- Gloria Cisneros Lenoir, Miguel Guzman Peredo, 1985, Miguel Hidalgo y la Ruta de la Independencia, Bertelsmann de Mexico, p. 87.

External links

- Mexico connect.com: "El Grito" (The Cry)

- Bibliography and Hemerography: Miguel Hidalgo and Costilla.

- Miguel Hidalgo and Costilla - Documents of 1810 and 1811.

- Chronology of Miguel Hidalgo and Costilla

- Mexico Celebrates Its Bicentennial - slideshow by Life magazine