Halogen bond

Halogen bonding (XB) is the non-covalent interaction that occurs between a halogen atom (Lewis acid) and a Lewis base. Although halogens are involved in other types of bonding (e.g. covalent), halogen bonding specifically refers to when the halogen acts as an electrophilic species.

Bonding

Comparison between hydrogen and halogen bonding:

- Hydrogen bonding:

- Halogen bonding:

In both cases, D (donor) is the atom, group, or molecule that is electron rich and donates them to the electron poor species (H or X). H is the hydrogen atom involved in hydrogen bonding (HB), and X is the halogen atom involved in XB. A (acceptor) is the electron poor species withdrawing the electron density from H or X, accordingly. H-A and X-A, when both atoms are considered together, are called hydrogen/halogen bond donors, accordingly, and D is HB/XB acceptor. A difference between HB and XB is since halogen atoms are Lewis bases, a halogen atom can both donate and accept in a halogen bond.

A parallel relationship can easily be drawn between halogen bonding and hydrogen bonding (HB). In both types of bonding, an electron donor/electron acceptor relationship exists. The difference between the two is what species can act as the electron donor/electron acceptor. In hydrogen bonding, a hydrogen atom acts as the electron acceptor and forms a non-covalent interaction by accepting electron density from an electron rich site (electron donor). In halogen bonding, a halogen atom is the electron acceptor. Simultaneously, the normal covalent bond between H or X and A weakens, so the electron density on H or X appears to be reduced. Electron density transfers results in a penetration of the van der Waals volumes.[1]

Halogens participating in halogen bonding include: iodine (I), bromine (Br), chlorine (Cl), and sometimes fluorine (F). All four halogens are capable of acting as XB donors (as proven through theoretical and experimental data) and follow the general trend: F < Cl < Br < I, with iodine normally forming the strongest interactions.[2]

Dihalogens (I2, Br2, etc.) tend to form strong halogen bonds. The strength and effectiveness of chlorine and fluorine in XB formation depend on the nature of the XB donor. If the halogen is bonded to an electronegative (electron withdrawing) moiety, it is more likely to form stronger halogen bonds.[3]

For example, iodoperfluoroalkanes are well-designed for XB crystal engineering. In addition, this is also why F2 can act as a strong XB donor, but fluorocarbons are weak XB donors because the alkyl group connected to the fluorine is not electronegative. In addition, the Lewis base (XB acceptor) tends to be electronegative as well and anions are better XB acceptors than neutral molecules.

Halogen bonds are strong, specific, and directional interactions that give rise to well-defined structures. Halogen bond strengths range from 5–180 kJ/mol. The strength of XB allows it to compete with HB, which are a little bit weaker in strength. Halogen bonds tend to form at 180° angles, which was shown in Odd Hassel’s studies with bromine and 1,4-dioxane in 1954. Another contributing factor to halogen bond strength comes from the short distance between the halogen (Lewis acid, XB donor) and Lewis base (XB acceptor). The attractive nature of halogen bonds result in the distance between the donor and acceptor to be shorter than the sum of van der Waals radii. The XB interaction becomes stronger as the distance decreases between the halogen and Lewis base.

History

In 1863, Frederick Guthrie gave the first report on the ability of halogen atoms to form well-defined adducts with electron donor species.[4] In his experiment, he added I2 to a saturated solution of ammonium nitrate to form NH3I2. When the compound was exposed to air, it spontaneously decomposed into ammonia and iodine which allowed Guthrie to conclude that he had formed NH3I2.

In the 1950s, Robert S. Mulliken developed a detailed theory of electron donor-acceptor complexes, classifying them as being outer or inner complexes.[5][6][7] Outer complexes were those in which the intermolecular interaction between the electron donor and acceptor were weak and had very little charge transfer. Inner complexes have extensive charge redistribution. Mulliken’s theory has been used to describe the mechanism by which XB formation occurs.

Around the same time period that Mulliken developed his theory, crystallographic studies performed by Hassel began to emerge and became a turning point in the comprehension of XB formation and its characteristics.

The first X-ray crystallography study from Hassel’s group came in 1954. In the experiment, his group was able to show the structure of bromine 1,4-dioxanate using x-ray diffraction techniques.[8] The experiment revealed that a short intermolecular interaction was present between the oxygen atoms of dioxane and bromine atoms. The O−Br distance in the crystal was measured at 2.71 Å, which indicates a strong interaction between the bromine and oxygen atoms. In addition, the distance is smaller than the sum of the van der Waals radii of oxygen and bromine (3.35 Å). The angle between the O−Br and Br−Br bond is about 180°. This was the first evidence of the typical characteristics found in halogen bond formation and led Hassel to conclude that halogen atoms are directly linked to electron pair donor with a bond direction that coincides with the axes of the orbitals of the lone pairs in the electron pair donor molecule.[9]

In the 1980s continued work was carried out using analytical methods such as infrared spectroscopy and Fourier transform spectroscopy. These methods allowed the isolation of complexes formed between Lewis bases and halogen molecules for further studies.

Applications

Crystal Engineering

Crystal engineering is a growing research area that bridges solid-state and supramolecular chemistry.[10] This unique field is interdisciplinary and merges traditional disciplines such as crystallography, organic chemistry, and inorganic chemistry. In 1971, Schmidt first established the field with a publication on photodimerization in the solid-state.[11] The more recent definition identifies crystal engineering as the utilization of the intermolecular interactions for crystallization and for the development of new substances with different desired physicochemical properties. Before the discovery of halogen bonding, the approach for crystal engineering involved using hydrogen bonding, coordination chemistry and inter-ion interactions for the development of liquid-crystalline and solid-crystalline materials. Furthermore, halogen bonding is employed for the organization of radical cationic salts, fabrication of molecular conductors, and creation of liquid crystal constructs. Since the discovery of halogen bonding, new molecular assemblies exist.[12] Due to the unique chemical nature of halogen bonding, this intermolecular interaction serves as an additional tool for the development of crystal engineering.[13]

The first reported use of halogen bonding in liquid crystal formation was by H. Loc Nguyen.[14] In an effort to form liquid crystals, alkoxystilbazoles and pentafluoroiodobenzene were used. Previous studies by Metrangolo and Resnati demonstrated the utility of pentafluoroiodobenzene for solid-state structures.[1] Various alkoxystilbazoles have been utilized for nonlinear optics and metallomesogens.[15] Using another finding of Resnati (e.g. N−I complexes form strongly), the group engineered halogen-bonded complexes with iodopentafluorobenzene and 4-alkoxystilbazoles. X-ray crystallography revealed a N−I distance of 2.811(4) Å and the bonding angle to be 168.4°. Similar N−I distances were measured in solid powders.[16] The N−I distance discovered is shorter than the sum of the Van Der Waals radii for nitrogen and iodine (3.53 Å). The single crystal structure of the molecules indicated that no quadrupolar interactions were present. The complexes in Figure 4 were found to be liquid-crystalline.

To test the notion of polarizability involvement in the strength of halogen bonding, bromopentafluorbenzene was used as a Lewis base. Consequently, verification of halogen bond complex formation wasn’t obtained. This finding provides more support for the dependence of halogen bonding on atomic polarizability. Utilizing similar donor-acceptor frameworks, the authors demonstrated that halogen bonding strength in the liquid crystalline state is comparable to the hydrogen-bonded mesogens.

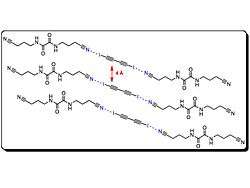

Preparation of poly(diiododiacetylene)

Applications utilizing properties of conjugated polymers emerged from work done by Heeger, McDiaramid, and Shirakawa with the discovery that polyacetylene is a conducting, albeit difficult to process material. Since then, work has been done to mimic this conjugated polymer’s backbone (e.g., poly(p-phenylenevinylene)). Conjugated polymers have many practical applications, and are used in devices such as photovoltaic cells, organic light-emitting diodes, field-effect transistors, and chemical sensors. Goroff et al. prepared ordered poly(diiododiacetylene) (PIDA) via prearrangement of monomer (2) with a halogen bond scaffolding.[17] PIDA is an excellent precursor to other conjugated polymers, as Iodine can be easily transformed. For instance, C−I cleavage is possible electrochemical reduction.[18]

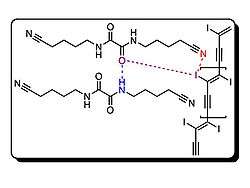

Crystal structures of monomer (2) are disordered materials of varying composition and connectivity. Hosts (3–7) were investigated for their molecular packing, primarily by studying co-crystals of monomer (2) and respective host. Both (3) and (4) pre-organized monomer (2), but steric crowding around the iodines prevented successful topological polymerization of the monomer. Hosts (5–7) utilize hydrogen bonds and halogen bonds to hold monomer (2) at an optimal distance from each other to facilitate polymerization.

In fact, when host 7 was used, polymerization occurred spontaneously upon isolation of the co-crystals. Crystal structures show the polymer strands are all parallel to the hydrogen-bonding network, and the host nitriles are each halogen-bonded to iodine atoms. Half of the iodine atoms in (1) in the crystal are in close contact to the oxalamide oxygen atoms. Oxygen atoms of host 7 are acting as both hydrogen and halogen bond acceptors.

Porous structures

Porous structures have a variety of uses. Many chemists and material scientists are working to improve metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) to store hydrogen to use in cars. These highly organized crystalline inclusion complexes have potential uses in catalysis and molecular separation devices. Molecular organization is often controlled via intermolecular forces such as hydrogen bonding. However, utilizing hydrogen bonding often limits the range of pore sizes available due to close packing.

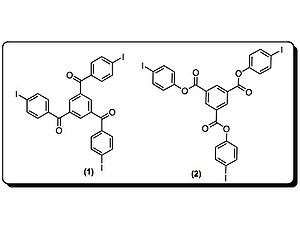

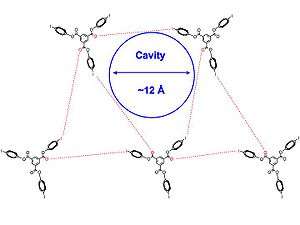

Pigge, et al., utilized halogen bonding interactions between amines, nitrogen heterocycles, carbonyl groups, and other organic halides, to construct their porous structures. This is significant because organic crystalline networks mediated by halogen bonds, an interaction significantly weaker than hydrogen bond, are rare.[19]

Crystal structures of 1 and 2 [below] were obtained in a variety of solvents, such as dichloromethane, pyridine, and benzene. The authors note that the porous inclusion complexes appear to be mediated in part by unprecedented I-π interactions and by halogen bond between iodine and carbonyl groups. The crystal structure [shown below] come together in a triangular array and molecules of 2 are approximately symmetric. Additionally, all of the sets of halogen bonding interactions are not identical, and all of the intermolecular interactions between halogen and halogen bond acceptor slightly exceed the sum of the Van der Waals radius, signifying a slightly weaker halogen bond, which leads to more flexibility in the structure. The 2D layers stack parallel to each other to produce channels filled with solvent.

Solvent interactions are also noted in the formation of the hexagonal structures, especially in pyridine and chloroform. Initially, crystals that form these solutions form channeled structures. Over time, new needle-like solvate-free structures form are packed tighter together, and these needles are actually the thermodynamically favored crystal. The authors hope to use this information to better understand the complementary nature of hydrogen bonds and halogen bonds in order to design small molecules predict structures.

Halogen Bonding in Biological Macromolecules

For some time, the significance of halogen bonding to biological macromolecular structure was overlooked. Based on single-crystal structures in the protein data bank (PDB) (July 2004 version), a study by Auffinger and others on single crystals structures with 3 Å resolution or better entered into the PDB revealed that over 100 halogen bonds were found in six halogenated-based nucleic acid structures and sixty-six protein-substrate complexes for halogen-oxygen interactions. Although not as frequent as halogen-oxygen interactions, halogen-nitrogen and halogen-sulfur contacts were identified as well.[20] These scientific findings provide a unique basis for elucidating the role of halogen bonding in biological systems.

On the bio-molecular level, halogen bonding is important for substrate specificity, binding and molecular folding.[21] In the case of protein-ligand interactions, the most common charge-transfer bonds with polarizable halogens involve backbone carbonyls and/or hydroxyl and carboxylate groups of amino acid residues. Typically in DNA and protein-ligand complexes, the bond distance between Lewis base donor atoms (e.g. O, S, N) and Lewis acid (halogen) is shorter than the sum of their Van der Waals radius. Depending on the structural and chemical environment, halogen bonding interactions can be weak or strong. In the case of some protein-ligand complexes, halogen bonds are energetically and geometrically comparable to that of hydrogen bonding if the donor-acceptor directionality remains consistent. This intermolecular interaction has been shown to be stabilizing and a conformational determinant in protein-ligand and DNA structures.

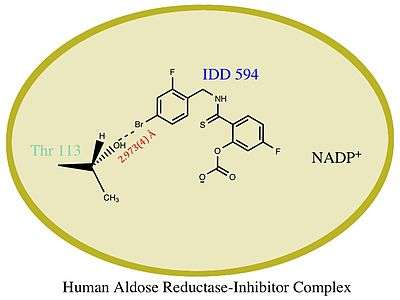

For molecular recognition and binding, halogen bonding can be significant. An example of this assertion in drug design is the substrate specificity for the binding of IDD 594 to human aldose reductase.[22] E.I. Howard reported the best resolution for this monomeric enzyme. This biological macromolecule consists of 316 residues, and it reduces aldoses, corticosteroids, and aldehydes. D-sorbitol, a product of the enzymatic conversion of D-glucose, is thought to contribute to the downstream effects of the pathology of diabetes.[23] Hence, inhibiting this enzyme has therapeutic merit.

Aldehyde-based and carboxylate inhibitors are effective but toxic because the functional activity of aldehyde reductase is impaired. Carboxylate and aldehyde inhibitors were shown to hydrogen bond with Trp 111, Tyr 48, and His 110. The “specificity pocket,” created as a result of inhibitor binding, consists of Leu 300, Ala 299, Phe 122, Thr 113, and Trp 111. For inhibitors to be effective, the key residues of interaction were identified to be Thr 113 and Trp 111. IDD 594 was designed such that the halogen would provide selectivity and be potent. Upon binding, this compound induces a conformational change that causes halogen bonding to occur between the oxygen of the Thr and the bromine of the inhibitor. The bond distance was measured to be 2.973(4) Å. It is this O−Br halogen bond that contributes to the large potency of this inhibitor for human aldose reductase rather than aldehyde reductase.

References

- 1 2 Metrangolo, P.; Resnati, G. (2001), "Halogen Bonding: A Paradigm in Supramolecular Chemistry", Chem. Eur. J, 7 (12): 2511–2519, doi:10.1002/1521-3765(20010618)7:12<2511::AID-CHEM25110>3.0.CO;2-T, PMID 11465442

- ↑ Politzer, P.; et al. (2007), "An Overview of Halogen Bonding", J. Mol. Model, 13 (2): 305–311, doi:10.1007/s00894-006-0154-7, PMID 17013631

- ↑ Metrangolo, P.; Neukirch, H; Pilati, T; Resnati, G. (2005), "Halogen Bonding Based Recognition Processes: A World Parallel to Hydrogen Bonding†", Acc. Chem. Res., 38 (5): 386–395, doi:10.1021/ar0400995, PMID 15895976

- ↑ Guthrie, F. (1863), "Xxviii.—On the Iodide of Iodammonium", J. Chem. Soc, 16: 239–244, doi:10.1039/js8631600239

- ↑ Mulliken, R.S. (1950), "Structures of Complexes Formed by Halogen Molecules with Aromatic and with Oxygenated Solvents1", J. Am. Chem. Soc, 72 (1): 600, doi:10.1021/ja01157a151

- ↑ Mulliken, R.S. (1952), "Molecular Compounds and their Spectra. II", J. Am. Chem. Soc, 74 (3): 811–824, doi:10.1021/ja01123a067

- ↑ Mulliken, R.S. (1952), "Molecular Compounds and their Spectra. III. The Interaction of Electron Donors and Acceptors", J. Phys. Chem., 56 (7): 801–822, doi:10.1021/j150499a001

- ↑ Hassel, O.; Hvoslef, J.; Vihovde, E. Hadler; Sörensen, Nils Andreas (1954), "The Structure of Bromine 1,4-Dioxanate", Acta Chem. Scand., 8: 873, doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.08-0873

- ↑ Hassel, O. (1970), "Structural Aspects of Interatomic Charge-Transfer Bonding", Science, 170 (3957): 497–502, Bibcode:1970Sci...170..497H, doi:10.1126/science.170.3957.497, PMID 17799698

- ↑ Braga, D.; Desiraju, Gautam R.; Miller, Joel S.; Orpen, A. Guy; Price, Sarah (Sally) L.; et al. (2002), "Innovation in Crystal Engineering", CrystEngComm, 4 (83): 500–509, doi:10.1039/b207466b

- ↑ Schmidt, G.M.J. (1971), "Photodimerization in the solid state", Pure Appl. Chem, 27 (4): 647–678, doi:10.1351/pac197127040647

- ↑ Metrangolo, P.; Resnati, Giuseppe; Pilati, Tullio; Liantonio, Rosalba; Meyer, Franck; et al. (2007), "Engineering Functional Materials by Halogen Bonding", J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem, 45 (1): 1–14, Bibcode:2007JPoSA..45....1M, doi:10.1002/pola.21725

- ↑ Metrangolo, Pierangelo; Resnati, Giuseppe; Pilati, Tullio; Terraneo, Giancarlo; Biella, Serena (2009), "Anion coordination and anion-templated assembly under halogen bonding control", CrystEngComm, 11 (7): 1187–1196, doi:10.1039/B821300C

- ↑ Nguyen, Loc; Al, H. et; Hursthouse, MB; Legon, AC; Bruce, DW (2004), "Halogen Bonding: A New Interaction for Liquid Crystal Formation", J. Am. Chem. Soc, 126 (1): 16–17, doi:10.1021/ja036994l, PMID 14709037

- ↑ Bruce, D.W. (2001), "The Materials Chemistry of Alkoxystilbazoles and Their Metal Complexes", Adv. Inorg. Chem, 52: 151–204, doi:10.1016/S0898-8838(05)52003-8

- ↑ Weingarth, M.; Raouafi, N.; Jouvelet, B.; Duma, L.; Bodenhausen, G.; Boujlel, K.; Scöllhorn, B.; Tekley, P. (2008), "Revealing molecular self-assembly and geometry of non-covalent halogen bonding by solid-state NMR spectroscopy", Chem. Commun. (45), pp. 5981–5983, doi:10.1039/b813237b

- ↑ Sun, A.; Lauher, J.W.; Goroff, N.S. (2006), "Preparation of Poly(Diiododiacetylene), an Ordered Conjugated Polymer of Carbon and Iodine", Science, 312 (5776): 1030–1034, Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1030S, doi:10.1126/science.1124621, PMID 16709780

- ↑ Sun, A.; Lauher, J.W.; Goroff, N.S. (2008), "Preparation of Poly(Diiododiacetylene), an Ordered Conjugated Polymer of Carbon and Iodine", Science, 312 (5776): 1030–1034, Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1030S, doi:10.1126/science.1124621, PMID 16709780

- ↑ Pigge, F.; Vangala, V.; Kapadia, P.; Swenson, D.; Rath, N.; Chem, Comm (2008), "Hexagonal crystalline inclusion complexes of 4-iodophenoxy trimesoate", Chemical Communications, 38: 4726–2728, doi:10.1039/b809592b

- ↑ Auffinger, P.; Hays, FA; Westhof, E; Ho, PS; et al. (2004), "Halogen Bonds in Biological Molecules", Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A, 101 (48): 16789–16794, Bibcode:2004PNAS..10116789A, doi:10.1073/pnas.0407607101, PMC 529416

, PMID 15557000

, PMID 15557000 - ↑ Steinrauf, L.K.; Hamilton, JA; Braden, BC; Murrell, JR; Benson, MD; et al. (1993), "X-ray crystal structure of the Ala-109-->Thr variant of human transthyretin which produces euthyroid hyperthyroxinemia", J. Biol. Chem., 268 (4): 2425–2430, PMID 8428916

- ↑ Howard, E.I.; et al. (2004), "Ultrahigh Resolution Drug Design I: Details of Interactions in Human Aldose Reductase-Inhibitor Complex at 0.66 Å", Proteins : Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics, 55 (4): 792–804, doi:10.1002/prot.20015, PMID 15146478

- ↑ Yabe-nishimura, C. (1998), "Aldose reductase in glucose toxicity: a potential target for the prevention of diabetic complications", Pharmacol Rev, 50 (1): 21–33, PMID 9549756

- ↑ Howard, E.I.; Sanishvili, R; Cachau, RE; Mitschler, A; Chevrier, B; Barth, P; Lamour, V; Van Zandt, M; et al. (2004), "Ultrahigh resolution drug design I: Details of interactions in human aldose reductase-inhibitor complex at 0.66 Å", Proteins : Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics, 55 (4): 792–804, doi:10.1002/prot.20015, PMID 15146478