Henri Mouhot

| Henri Mouhot | |

|---|---|

|

A drawing of Henri Mouhot done by H. Rousseau from a photograph | |

| Born |

May 15, 1826 Montbéliard, Doubs, France |

| Died |

November 10, 1861 (aged 35) Naphan, Laos |

| Nationality | French |

| Fields | Natural history |

| Known for | Angkor |

Henri Mouhot (Born May 15, 1826 - November 10, 1861) Was a French naturalist and explorer who alerted the West to the ruins of Angkor, capital of the ancient Khmer civilization of Cambodia (Kampuchea).[1] From a Protestant family living in the Franche-Comté, Mouhot studied at the collège Cuvier in Montbéliard, his hometown. At the age of 18 he left Montbéliard for a teaching position. In the Russian town of St. Petersburg he taught French at the military academy.

Driven by his desire for travel and the up-and-coming art of photography (daguerréotype), he visited Italy and Germany. Once in England, he married Anna Park, possibly the grand-daughter of the explorer Mungo Park. In 1856, the couple settled down in the Isle of Jersey.

During this period, Henri Mouhot honed his skills in natural sciences, especially in ornithology and conchyliology.

He died near Naphan, Laos on November 10, 1861. He is remembered mostly in connection to Angkor. Mouhot's tomb is located just outside Ban Phanom, to the east of Luang Prabang.

Early life

He traveled throughout Europe with his brother Charles, studying photographic techniques developed by Louis Daguerre. In 1856, he began devoting himself to the study of Natural Science. Upon reading "The Kingdom and People of Siam" by Sir James Bowring in 1857, Mouhot decided to travel to Indochina to conduct a series of botanical expeditions for the collection of new zoological specimens. His initial requests for grants and passage were rejected by French companies and the government of Napoleon III. The Royal Geographical Society and the Zoological Society of London lent him their support, and he set sail for Bangkok, via Singapore.

Expeditions

From his base in Bangkok in 1858, Mouhot made four journeys into the interior of Siam, Cambodia and Laos. Over a period of three years before he died, he endured extreme hardships and fended off wild animals, to explore some previously uncharted jungle territory.

On his first expedition, he visited Ayutthaya, the former capital of Siam (already charted territory), and gathered an extensive collection of insects, as well as terrestrial and river shells, and sent them on to England.

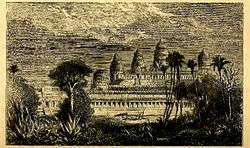

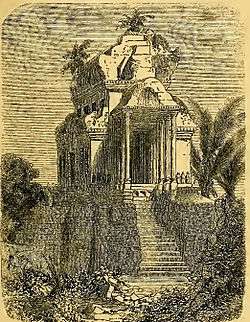

In January 1860, at the end of his second and longest journey, he reached Angkor (already charted territory) — an area spread over more than 400 km²., consisting of many sites of ancient terraces, pools, moated cities, palaces and temples, the most famous of which is Angkor Wat. He recorded this visit in his travel journals, which included three weeks of detailed observations. These journals and illustrations were later incorporated into Voyage dans les royaumes de Siam, de Cambodge, de Laos which were published posthumously.

Angkor

Mouhot is often mistakenly credited with "discovering" Angkor, although Angkor was never lost — the location and existence of the entire series of Angkor sites was always known to the Khmers and had been visited by several westerners since the 16th century. Mouhot mentions in his journals that his contemporary Father Charles Emile Bouillevaux, a French missionary based in Battambang, had reported that he and other Western explorers and missionaries had visited Angkor Wat and the other Khmer temples at least five years before Mouhot. Father Bouillevaux published his accounts in 1857: "Travel in Indochina 1848–1846, The Annam and Cambodia". Previously, a Portuguese trader Diogo do Couto visited Angkor and wrote his accounts about it in 1550, and the Portuguese monk Antonio da Magdalena had also written about his visit to Angkor Wat in 1586.

Mouhot did, however, popularise Angkor in the West. Perhaps none of the previous European visitors wrote as evocatively as Mouhot, who included interesting and detailed sketches. In his posthumously published "Travels in Siam, Cambodia and Laos," Mouhot compared Angkor to the pyramids, for it was popular in the West at that time to ascribe the origin of all civilization to the Middle East. For example, he described the Buddha heads at the gateways to Angkor Thom as "four immense heads in the Egyptian style" and wrote of Angkor:

"One of these temples—a rival to that of Solomon, and erected by some ancient Michael Angelo—might take an honourable place beside our most beautiful buildings. It is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome, and presents a sad contrast to the state of barbarism in which the nation is now plunged."

Mouhot also wrote that:

"At Ongcor, there are ...ruins of such grandeur... that, at the first view, one is filled with profound admiration, and cannot but ask what has become of this powerful race, so civilized, so enlightened, the authors of these gigantic works?"

Such quotations may have given rise to the popular misconception that Mouhot had found the abandoned ruins of a lost civilisation. The Royal Geographical Society and The Zoological Society, both interested in announcing new finds, seemed to have encouraged the rumor that Mouhot — whom they had sponsored to chart mountains and rivers and catalog new species — had discovered Angkor. Mouhot himself erroneously asserted that Angkor was the work of an earlier civilization than the Khmer. For although the very same civilization which built Angkor was alive and right before his eyes, he considered them in a "state of barbarism" and could not believe they were civilized or enlightened enough to have built it. He assumed that the authors of such grandeur were a disappeared race and mistakenly dated Angkor back over two millennia, to around the same era as Rome. The true history of Angkor Wat was later pieced together from the book The Customs of Cambodia written by Temür Khan's envoy Zhou Daguan to Cambodia in 1295-1296[2] and from stylistic and epigraphic evidence accumulated during the subsequent clearing and restoration work carried out across the whole Angkor site. It is now known that the dates of Angkor's habitation were from the early 9th to the early 15th centuries.

Colonialism

Some have argued that Mouhot may have been a tool for French expansionism and the annexation of territories which followed shortly after his death. Mouhot himself, however, did not seem to be a hardcore colonialist, for he occasionally doubted the beneficial effects of European colonisation:

"Will the present movement of the nations of Europe towards the East result in good by introducing into these lands the blessings of our civilization? Or shall we, as blind instruments of boundless ambition, come hither as a scourge, to add to their present miseries?"

Death and legacy

Mouhot died of a malarial fever on his 4th expedition, in the jungles of Laos. He had been visiting Luang Prabang, capital of the Lan Xang kingdom, one of 3 kingdoms which eventually merged into what can be known as modern day Laos, and was under the patronage of the king. Two of his servants buried him near a French mission in Naphan, by the banks of the Nam Khan river. Mouhot's favourite servant, Phrai, transported all of Mouhot's journals and specimens back to Bangkok, from where they were shipped to Europe.

A modest monument was erected over his grave in 1867 under the orders of French commander Ernest Doudart de Lagrée, who gave him this eulogy:

"We found everywhere the memory of our compatriot who, by the uprightness of his character and his natural benevolence, had acquired the regard and the affection of the natives."

The monument was destroyed by the overflow of the river Nam Khan. It was replaced in 1887 by a more durable crypt monument, and a maisonnette was built nearby to house and feed visitors to the white shrine. Some restoration work was done on the tomb in 1951 by the EFEO (Ecole Française d'Extrème Orient—The French School of the Far East).

Mouhot's tomb was consumed by the jungle and lost until it was accidentally rediscovered in 1989 by a French Laos scholar, Jean-Michel Strobino, who played a part in rehabilitating it with the support of the French embassy and the Municipality of Montbeliard, Mouhot's birth town. A new plaque was fixed to one end of the crypt in 1990 to commemorate this rediscovery. The location is now known to hotels and tourist operators in Luang Prabang, and a minivan or "tuk tuk" may be hired to take one the 10 km from town to visit it. This entails a walk down a steep track on the southern bank of river Nam Khan, over a small wooden bridge, and then up to a well-cleared track to the tomb, altogether about 150 meters. A new road being constructed nearby (June 2013) will make access easier. The tomb is still quite near the river (only about 20m), and access by boat from town should be possible. As more people visit the tomb, the pathway hopefully will be improved, as it is quite slippery after rain; sensible shoes are a must.

The popularity of Angkor generated by Mouhot's writings led to the popular support for a major French role in its study and preservation. The French carried out the majority of research work on Angkor until recently.

Borne of the posthumous misattribution to Henri Mouhot discovering Angkor, the idea that Angkor was lost and (re)discovered by Europeans lingers on, reinforced by Hollywood images of Europeans hacking through jungles to stumble upon the lost ruins of Angkor. An uninformed host of Discovery Channel's Beyond Borders program described just such a scenario of Mouhot, perpetuating the myth.

Two species of Asian reptiles are named in his honor: Cuora mouhotii, a turtle; and Oligodon mouhoti, a snake.[3]

Mouhot's writings

Mouhot's travel journals are immortalized in Voyage dans les royaumes de Siam, de Cambodge, de Laos et autres parties centrales de l'Indochine (published 1863, 1864) -- English title: Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China, Cambodia and Laos During the Years 1858,1859, and 1860 (see Literature section below)

Literature

- Travels in Siam, Cambodia, Laos, and Annam—Henri Mouhot, M. Mouhot—ISBN 974-8434-03-6

- Travels in Siam, Cambodia and Laos, 1858-1860—Henri Mouhot, Michael Smithies - ISBN 0-19-588614-3

- Illustrated by Profusely illus in b/w. - Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos During the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860—Mouhot, M. Henri—ISBN 974-8495-11-6

References

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- The history of Henri Mouhot's shrine near Ban Phanom (1861-1990), by J.M. Strobino : https://www.academia.edu/11773322/La_sépulture_dHenri_MOUHOT_à_Luang_Prabang_Laos_

- Angkor Guide, published in Siem Reap by the Cambodian Ministry of Information

- The Siem Reap Angkor Visitors Guide (quarterly—March–May 2005), Canby publications (www.canbypublications.com)

- University of California Irvine, Cambodian Students Organization, Knowledge Section (see http://spirit.dos.uci.edu/cambo/)

- Ron Emmon's Biographies (http://ronemmons.com/biographies/mouhot/)

- Angkor.com - The Forgotten Crypt of Henri Mouhot (1826–1861) (see http://www.angkor.com/hd.shtml)

- German Wikipedia: de:Henri Mouhot

- Henri Mouhot's diary; travels in the central parts of Siam, Cambodia and Laos during the years 1858-61.

- Angkor Wat Online http://angkor.wat.online.fr/dec-henri_mouhot.htm

- Bryson, 2003, A Short History of Nearly Everything, chap. 6, ISBN 0-552-15174-2

- Petrotchenko, Michel (2011), Focusing on the Angkor Temples: The Guidebook, 383 pages, Amarin Printing and Publishing, 2nd edition, ISBN 978 616 305 096 0

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Henri-Mouhot

- ↑ Translated into French as early as 1819, perhaps Mouhot knew of it

- ↑ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael. 2011. The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Mouhot", p. 183).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henri Mouhot. |

- http://www.angkorwat.org/html/L2225.html [broken link]

- Short biography (in French)

- http://www.kh.refer.org/cbodg_ct/decouvert_kh/culture_kh/livres/mouhot.htm (in French) [broken link]

- http://www.insecula.com/contact/A010818.html (in French)

- http://www.angkor.com/hd.shtml [broken link]