History of the Maryland Militia in the Civil War

Like other border states, Maryland found herself in a difficult position at the start of the American Civil War, with loyalties divided between North and South. Although Maryland herself remained in the Union, Maryland militia units fought on both sides of the Civil War. Many militia members travelled south at the start of the war, crossing the Potomac River to join the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.

Harper's Ferry

In 1859 units of the Maryland Militia participated in the suppression of John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, an abortive attempt to ignite a slave rebellion.[1] Major General George H. Steuart personally led six companies of Militia: the City Guard, Law Greys and Shields Guard from Baltimore, and the United Guards, Junior Defenders and Independent Riflemen from the city of Frederick.[2] The departing Baltimore militia were cheered on by substantial crowds of citizens and well-wishers.[3] After Harper's Ferry, militias in the South began to grow in importance as Southerners began to fear slave rebellion inspired by Northern Abolitionists.[4]

The coming of war

From 1841 to 1861 the senior militia general was George H. Steuart, commander of the First Light Division.[5] Until the Civil War he would be the senior commander of the Maryland Volunteers.

In 1833 a number of Baltimore regiments were formed into a brigade, and Steuart was promoted from colonel to brigadier general.[6] From 1841 to 1861 he was Commander of the First Light Division, Maryland Volunteer Militia.[5] Until the Civil War he would be the Commander-in-Chief of the Maryland Volunteers.[1][7] The First Light Division comprised two brigades: the 1st Light Brigade and the 2nd Brigade. The First Brigade consisted of the 1st Cavalry, 1st Artillery, and 5th Infantry regiments. The 2nd Brigade was composed of the 1st Rifle Regiment and the 53rd Infantry Regiment, and the Battalion of Baltimore City Guards.[8]

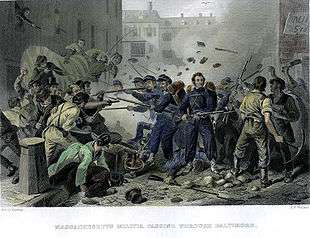

Baltimore Riots

By April 1861 it had become clear that war was inevitable. On April 16 Steuart's son, George H. Steuart, then an officer in the United States Army, resigned his captain's commission to join the Confederacy.[9] On April 19 Baltimore was disrupted by riots, during which Southern sympathizers attacked Union troops passing through the city by rail. Steuart's son commanded one of the Baltimore city militias during the disturbances of April 1861, following which Federal troops occupied the city. In a letter to his father, the younger Steuart wrote:

- "I found nothing but disgust in my observations along the route and in the place I came to - a large majority of the population are insane on the one idea of loyalty to the Union and the legislature is so diminished and unreliable that I rejoiced to hear that they intended to adjourn...it seems that we are doomed to be trodden on by these troops who have taken military possession of our State, and seem determined to commit all the outrages of an invading army." [10]

Steuart himself was strongly sympathetic to the Confederacy and, perhaps knowing this, Governor Hicks did not call out the militia to suppress the riots.[11] On May 13, 1861 Union troops occupied the state, restoring order and preventing a vote in favour of Southern secession. Steuart moved south for the duration of the American Civil War, and much of the general's property was confiscated by the Federal Government as a consequence. Old Steuart Hall was confiscated by the Union Army and Jarvis Hospital was erected on the estate, to care for Federal wounded.[12] However, many members of the newly formed Maryland Line in the Confederate army would be drawn from the state militia.[13]

Maryland militia units fought on both sides of the Civil War. At the Battle of Front Royal, the Union 1st Maryland regiment was engaged and defeated by the Confederate 1st Maryland Regiment.

The lineage of the Confedrate 1st Maryland is perpetuated by the 175th Infantry Regiment, whose lineage dates back to 1774.

Notes

- 1 2 Hartzler, Daniel D., p.13, A Band of Brothers: Photographic Epilogue to Marylanders in the Confederacy Retrieved March 1, 2010

- ↑ Field, p.33

- ↑ Andrews, p.497

- ↑ Ken Burns, The American Civil War

- 1 2 Sullivan David M., The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War: The First Year, p.286, White Mane Publishing (1997). Retrieved Jan 13 2010

- ↑ Griffith, Thomas W., p.257, Annals of Baltimore, 1833 Retrieved February 28, 2010

- ↑ Niles' Weekly Register, Volume 14, by Hezekiah Niles (1818) Retrieved Jan 15 2010

- ↑ Field, Ron, et al., p.33, The Confederate Army 1861-65: Missouri, Kentucky & Maryland Osprey Publishing (2008), Retrieved May 10, 2010

- ↑ Cullum, George Washington, p.226, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Retrieved Jan 16 2010

- ↑ Mitchell, Charles W., p.102, Maryland Voices of the Civil War. Retrieved February 26, 2010

- ↑ Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634-1980 by Robert J. Brugger, Johns Hopkins University Press (1996) Retrieved Jan 15 2010

- ↑ Nelker, p.120

- ↑ Goldsborough, p.9

References

- Field, Ron, et al., The Confederate Army 1861-65: Missouri, Kentucky & Maryland Osprey Publishing (2008), Retrieved March 4, 2010

- Goldsborough, W. W., The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army, Guggenheimer Weil & Co (1900), ISBN 0-913419-00-1.

- Hanson, George Adolphus, Old Kent: The Eastern Shore of Maryland: Notes Illustrative of the Most Ancient Records Of Kent County, Maryland (1876), unknown publisher.

- Nelker, Gladys P., The Clan Steuart, Genealogical Publishing (1970).

- Papenfuse, Edward C. et al., Archives of Maryland, Historical List, new series, Vol. 1. Annapolis, MD: Maryland State Archives (1990).

- Pfanz, Harry W., Gettysburg - Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC (1993).

- Richardson. Hester Dorey, Side-Lights on Maryland History: With Sketches of Early Maryland Families, Tidewater Publishing, 1967. ASIN: B00146BDXW, ISBN 0-8063-0296-8, ISBN 978-0-8063-0296-6.

- Steuart, George H., Letter to the National Intelligencer dated November 19, 1860, unpublished, Archive of the Maryland Historical Society.

- Steuart, William Calvert, Article in Sunday Sun Magazine, "The Steuart Hill Area's Colorful Past", Baltimore, February 10, 1963.

- White, Roger B, Article in The Maryland Gazette, "Steuart, Only Anne Arundel Rebel General", November 13, 1969.