In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach

| In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | Court of Appeal of New Zealand |

| Decided | 6 March 1963 |

| Citation(s) | [1963] NZLR 461 |

| Case history | |

| Prior action(s) | [1960] NZLR 673 |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Gresson P, North and T.A. Gresson JJ |

| Keywords | |

| Foreshore and seabed, Aboriginal title, Ninety Mile Beach | |

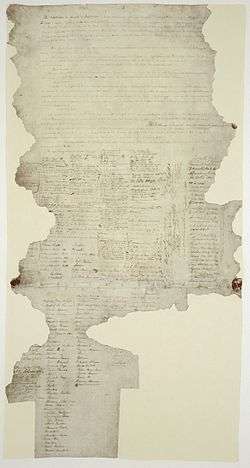

In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach was a decision of the Court of Appeal holding that Maori could not hold title to the foreshore because of the effect of section 147 of the Harbours Act 1878, (later section 150 of the Harbours Act 1950); and because investigation of title to land adjacent to the sea by the Maori Land Court had extinguished rights to land below the high water mark.[1] The decision was overturned in 2003 by Ngati Apa v Attorney-General.

Background

The plaintiff in the case, Waata Tepania, was the "Chairman of the Taitokerau Maori District Council, a member of the New Zealand Maori Council, and a member of both the Taitokerau and Aupouri Maori Trust Boards, Mr Tepania was a leader and elder of both the Aupouri and Rarawa tribes. A resident at Ahipara, he was born at Wai-mahana and as a lad attended the most northerly school in New Zealand — Te Hapua."[2]

The background to the case was neatly summarised by Justice T.A. Gresson:

This was an application under s. 161 of the Maori Affairs Act 1953 by Waata Hone Tepania for an investigation of title, and for the issue of a freehold order in respect of the foreshore of the Ninety-Mile Beach in North Auckland. It was heard by the Maori Land Court in November 1957 and the Court found as a fact that immediately before the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 the Te Aupouri and Te Rarawa Tribes owned and occupied the foreshore in question according to their customs and usages. The Chief Judge, however, stated a case, pursuant to s. 67 of the Maori Affairs Act 1953, for the opinion of the Supreme Court on two substantial questions of law, which — in abbreviated form — may be stated as follows:1. Has the Maori Land Court jurisdiction to investigate title to, and to issue freehold orders in respect of the foreshore — namely, that part of the land which lies between mean high-water mark and mean low-water mark?

2. If so, is the Maori Land Court prohibited from exercising this jurisdiction by reason of a Proclamation issued by the Governor under s. 4 of the Native Lands Act 1867 on 29 May 1872?[3]

In the Supreme Court, Justice Turner stated that "s 150 of the Harbours Act 1950 operated as "an effective restriction upon the jurisdiction of the Maori Land Court" which in terms of the statute was in effect "forbidden to undertake the investigation of the application."" [4]

Waata Tepania appealed Turner J's decision to the Court of Appeal.

Judgments

Justices North and T. A. Gresson gave judgments dismissing the appeal with which President Gresson concurred. Justice North holds as a preliminary point that the Crown is the only "legal source of private title", and that "on the assumption of British sovereignty — apart from the Treaty of Waitangi — the rights of the Maoris to their tribal lands depended wholly on the grace and favour of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, who had an absolute right to disregard the Native title to any lands in New Zealand, whether above high-water mark or below high-water mark."[5]

The judgements contained two principal reasons for denying the Maori Land Court the jurisdiction to investigate title to the foreshore. Firstly, the judges held that the Court was prevented by the Harbour Acts of 1878 and 1950. Secondly, the judges held that Maori Land Court investigations of title to land adjacent to the sea had extinguished customary rights below the high water mark.

North J

In addition to holding that section 147 of the Harbours Act 1878 prevented the Maori Land Court from investigating title to the foreshore, Justice North held that section 12 of the Crown Grants Act 1866 had the effect of leaving ownership of the foreshore with the Crown when the ocean was "described as being the boundary of the land".[6]

As the learned Solicitor-General submitted might be the case, I am of opinion that once an application for investigation of title to land having the sea as one of its boundaries was determined, the Maori customary communal rights were then wholly extinguished. If the Court made a freehold order or its equivalent fixing the boundary at low-water mark and the Crown accepted that recommendation, then without doubt the individuals in whose favour the order was made or their successors gained a title to low-water mark. If, on the other hand, the Court thought it right to fix the boundary at high-water mark, then the ownership of the land between high-water mark and low-water mark remained with the Crown, freed and discharged from the obligations which the Crown had undertaken when legislation was enacted giving effect to the promise contained in the Treaty of Waitangi. Finally, as it would appear must often have been the case, if in the grant the ocean sea or any sound bay or creek affected by the ebb and flow of the tide was described as forming the boundary of the land, then by virtue of the provisions of s. 12 of the Crown Grants Act 1866 the ownership of the land between high-water mark and low-water mark likewise remained in the Crown.[7]

T.A. Gresson J

Justice T.A. Gresson cited section 147 of the Harbours Act 1878:

No part of the shore of the sea or of any creek, bay, arm of the sea, or navigable river communicating therewith, where and so far up as the tide flows and re-flows, nor any land under the sea or under any navigable river, except as may already have been authorised by or under any Act or Ordinance, shall be leased, conveyed, granted or disposed of to any Harbour Board or any other body (whether incorporated or not) or to any person or persons without the special sanction of an Act of the General Assembly.[8]

T.A. Gresson concluded in light of the Harbours Act,

"The section in the Harbours Act is in my opinion an effective restriction upon the jurisdiction of the Maori Land Court. The section speaks to prohibit all Courts, all officials, every person, from doing acts whose effect may be to purport to grant to any person any part of the foreshore. The present application is designed to obtain from the Maori Land Court an order having exactly that effect: therefore it must follow that the Maori Land Court is forbidden to undertake the investigation of the application. I must accordingly resolve the first question posed to me in favour of the Crown, and the answer to that question will accordingly be "No"."[9]

Ngati Apa v Attorney-General

The Court of Appeal overturned the ratio of In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach in its 2003 decision Ngati Apa v Attorney-General. The Court explicitly overruled the decision both on the preliminary point on the source of Aboriginal title and on the specific issues of statutory interpretation. Reaffirming the doctrine of native title established in R v Symonds, Chief Justice Elias stated:

The transfer of sovereignty did not affect customary property. They are interests preserved by the common law until extinguished in accordance with law. I agree that the legislation relied on in the High Court does not extinguish any Maori customary property in the seabed or foreshore. I agree with Keith and Anderson JJ and Tipping J that In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach was wrong in law and should not be followed. In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach followed the discredited authority of Wi Parata v Bishop of Wellington (1877) 3 NZ Jur (NS) SC 72, which was rejected by the Privy Council in Nireaha Tamaki v Baker [1901] AC 561. This is not a modern revision, based on developing insights since 1963. The reasoning the Court applied in In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach was contrary to other and higher authority and indeed was described at the time as “revolutionary”.[10]

Elias CJ explained the proper interpretation of the Harbours Acts:

Such legislation, by its terms, applied to future grants. It did not disturb any existing grants. Indeed, substantial areas of seabed and foreshore had already passed into the ownership of Harbour Boards and private individuals by 1878. I agree with the conclusion of Keith and Anderson JJ that the legislation cannot properly be construed to have confiscatory effect. Although a subsequent vesting order after investigation under the Maori Affairs Act 1953 was “deemed” a Crown grant (s162), that was a conveyancing device only and applied by operation of law. It was not a grant by executive action. Only such grants from Crown land were precluded for the future by the legislation. More importantly, the terms of s150 are inadequate to effect an expropriation of Maori customary property.[11]

Elias CJ also noted that,

Just as the investigation through the Maori Land Court of the title to customary land could not extinguish any customary property in contiguous land on shore beyond its boundaries, I consider that an investigation and grant of coastal land cannot extinguish any property held under Maori custom in lands below high water mark.[12]

References

- ↑ In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach [1963] NZLR 461

- ↑ "HAERE KI O KOUTOU TIPUNA". National Library of New Zealand. Te Ao Hou, the Maori Magazine. March 1969. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach [1963] NZLR 461 at 475-476.

- ↑ In re an Application for Investigation of Title to the Ninety Mile Beach (Wharo Oneroa a Tohe) [1960] NZLR 673.

- ↑ In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach [1963] NZLR 461 at 468.

- ↑ In re the Ninety-Mile Beach [1963] NZLR 461at 473.

- ↑ In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach [1963] NZLR 461 at 463.

- ↑ Harbours Act 1878, s 147.

- ↑ In Re the Ninety-Mile Beach [1963] NZLR 461 at 480.

- ↑ Ngati Apa v Attorney-General [2003] NZCA 117 at [13].

- ↑ Ngati Apa v Attorney-General [2003] NZCA 117 at [60].

- ↑ Ngati Apa v Attorney-General [2003] NZCA 117 at [88].