Insect bites and stings

| Insect bites and stings | |

|---|---|

| |

| Aedes aegypti, the yellow fever mosquito, biting | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | emergency medicine |

| ICD-10 | T14.1, X23-X25, W57 |

| ICD-9-CM | 919.4, 989.5, E905.3, E905.5, E906.4 |

| MedlinePlus | 000033 |

| MeSH | D007299 |

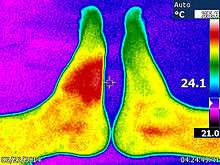

Insect bites and stings occur when an insect is agitated and seeks to defend itself through its natural defense mechanisms, or when an insect seeks to feed off the bitten person. Some insects inject formic acid, which can cause an immediate skin reaction often resulting in redness and swelling in the injured area. Stings from fire ants, bees, wasps and hornets are usually painful, and may stimulate a dangerous allergic reaction called anaphylaxis for at-risk patients, and some wasps can also have a powerful bite along with a sting. Bites from mosquitoes and fleas are more likely to cause itching than pain.

The skin reaction to insect bites and stings usually lasts for up to a few days. However, in some cases the local reaction can last for up to two years. These bites are sometimes misdiagnosed as other types of benign or cancerous lesions.[1]

Signs and symptoms

The reaction to a sting is of three types. The normal reaction involves the area around the bite with redness, itchiness, and pain. A large local reaction occurs when the area of swelling is greater than 5 cm. Systemic reactions are when symptoms occur in areas besides that of the bites.[2]

With insect stings a large local reaction may occur (an area of skin redness greater than 10 cm in size).[3] It can last one to two days.[3] It occurs in about 10% of those bitten.[4]

Feeding bites

Feeding bites have characteristic patterns and symptoms, a function of the feeding habits of the offending pest and the chemistry of its saliva.

| Pest | Preferred body part | Felt at time of bite | Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| mosquitoes | exposed appendages | often | Low raised welt, itches several hours. |

| midges and no-see-ums | exposed appendages | usually | Itches several hours. |

| fleas | prefer ankles and bare feet | usually | May make red itchy welt; several days. Later bites are less severe. |

| biting flies (Tabanidae) | any exposed skin | painful and immediate | Painful welt, several hours. |

| bed bugs | appendages, neck, exposed skin | usually not | Low red itchy welts, usually several together resembling rash, slow to develop and can last weeks. |

| lice | pubic area or scalp | usually not | Infested area intensely itchy, with red welts at bite sites. |

| larval ticks | Anywhere on body, but prefer covered skin, crevices. | Usually not; may be scratched off before they are seen. | Intensely itchy red welts lasting over a week. |

| adult ticks | covered skin, crevices, entire body | usually not | Itchy welt, several days. May transmit diseases |

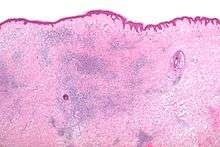

Microscopic appearance

The histomorphologic appearance of insect bites is usually characterized by a wedge-shaped superficial dermal perivascular infiltrate consisting of abundant lymphocytes and scattered eosinophils. This appearance is non-specific, i.e. it may be seen in a number of conditions including:[5]

- Drug reactions,

- Urticarial reactions,

- Prevesicular early stage of bullous pemphigoid, and

- HIV related dermatoses.

See also

- List of biting or stinging arthropods

- Spider bite

- Insect bite relief stick

- Schmidt Sting Pain Index

- Bee sting

- Allergy

References

- ↑ Allen, Arthur C. (March 1948). "Persistent "Insect Bites" (Dermal Eosinophilic Granulomas) Simulating Lymphoblastomas, Histiocytoses, and Squamous Cell Carcinomas". Am J Pathol. 24 (2): 367–387. PMC 1942711

. PMID 18904647.

. PMID 18904647. - ↑ Goddard, Jerome (2002). Physician's guide to arthropods of medical importance. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-8493-1387-2.

- 1 2 Ludman, SW; Boyle, RJ (2015). "Stinging insect allergy: current perspectives on venom immunotherapy.". Journal of asthma and allergy. 8: 75–86. doi:10.2147/JAA.S62288. PMC 4517515

. PMID 26229493.

. PMID 26229493. - ↑ Maynard, Robert J. Flanagan, Alison L. Jones ; with a section on antidotes and chemical warfare by Timothy C. Marrs and Robert L. (2003). Antidotes. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 118. ISBN 9780203485071. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ↑ Alsaad, KO.; Ghazarian, D. (Dec 2005). "My approach to superficial inflammatory dermatoses.". J Clin Pathol. 58 (12): 1233–41. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.027151. PMC 1770784

. PMID 16311340.

. PMID 16311340.

External links

- Venomous Arthropods chapter in United States Environmental Protection Agency and University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences National Public Health Pesticide Applicator Training Manual