Italian general election, 1924

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

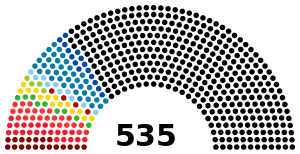

General elections were held in Italy on 6 April 1924.[1] They were held under the Acerbo Law, which stated that the party with the largest share of the votes would automatically receive two-thirds of the seats in Parliament as long as they received over 25% of the vote.[2] The National List of Benito Mussolini (an alliance with Liberals and Conservatives) used intimidation tactics,[2] resulting in a landslide victory and a subsequent two-thirds majority.

This was the last free election in Italy until 1946.

Electoral system

In November 1923 the Parliament approved the Acerbo Law, which stated that the party gaining the largest share of the votes – provided they had gained at least 25 percent of the votes – gained two-thirds of the seats in parliament. The remaining third was shared amongst the other parties proportionally.[3]

Historical background

On 22 October 1922 the young leader of the National Fascist Party, Benito Mussolini, attempted a coup d'état which was titled by the Fascist propaganda, the March on Rome, in which took part almost 30,000 fascists. The quadrumvirs leading the Fascist Party, General Emilio De Bono, Italo Balbo (one of the most famous ras), Michele Bianchi and Cesare Maria de Vecchi, organized the March while the Duce stayed behind for most of the march, though he allowed pictures to be taken of him marching along with the Fascist marchers. Generals Gustavo Fara and Sante Ceccherini assisted to the preparations of the March of 18 October. Other organizers of the march included the Marquis Dino Perrone Compagni and Ulisse Igliori.

On 24 October 1922, Mussolini declared before 60,000 people at the Fascist Congress in Naples: "Our program is simple: we want to rule Italy."[4] Blackshirts occupied some strategic points of the country and began to move on the capital. On 26 October, former prime minister Antonio Salandra warned current Prime Minister Luigi Facta that Mussolini was demanding his resignation and that he was preparing to march on Rome. However, Facta did not believe Salandra and thought that Mussolini would govern quietly at his side. To meet the threat posed by the bands of fascist troops now gathering outside Rome, Luigi Facta (who had resigned but continued to hold power) ordered a state of siege for Rome. Having had previous conversations with the king about the repression of fascist violence, he was sure the king would agree.[5] However, King Victor Emmanuel III refused to sign the military order.[6] On 28 October, the King handed power to Mussolini, who was supported by the military, the business class, and the right-wing.

The march itself was composed of fewer than 30,000 men, but the king feared a civil war, did not consider strong enough previous government while Fascism was no longer seen as a threat to the establishment. Mussolini was asked to form his cabinet on 29 October 1922, while some 25,000 Blackshirts were parading in Rome. Mussolini thus legally reached power, in accordance with the Statuto Albertino, the Italian Constitution. The March on Rome was not the conquest of power which Fascism later celebrated but rather the precipitating force behind a transfer of power within the framework of the constitution. This transition was made possible by the surrender of public authorities in the face of fascist intimidation. Many business and financial leaders believed it would be possible to manipulate Mussolini, whose early speeches and policies emphasized free market and laissez faire economics.[7] This proved overly optimistic, as Mussolini's corporatist view stressed total state power over businesses as much as over individuals, via governing industry bodies ("corporations") controlled by the Fascist party, a model in which businesses retained the responsibilities of property, but few if any of the freedoms.

Even though the coup failed in giving power directly to the Fascist Party, it nonetheless resulted in a parallel agreement between Mussolini and King Victor Emmanuel III that made Mussolini the head of the Italian government

A few weeks after the election, the leader of the United Socialist Party, Giacomo Matteotti, requested, during his speech in front of the Parliament, that the elections be annulled because of the irregularities.[8]

But after a few days, on June 10 Matteotti was assassinated by Fascist Blackshirts and his murder provoked a momentary crisis in the Mussolini government. Mussolini ordered a cover-up, but witnesses saw the car that transported Matteotti's body parked outside Matteotti's residence, which linked Amerigo Dumini, a fascist prominent in Mussolini's personal escort, to the murder.

Mussolini later confessed that a few resolute men could have altered public opinion and started a coup that would have swept fascism away. Dumini was imprisoned for two years. On his release Dumini allegedly told other people that Mussolini was responsible, for which he served further prison time.

The opposition parties responded weakly or were generally unresponsive. Many of the socialists, liberals, and moderates boycotted Parliament in the Aventine Secession, hoping to force Victor Emmanuel to dismiss Mussolini.

On 31 December 1924, Blackshirt leader smet with Mussolini and gave him an ultimatum—crush the opposition or they would do so without him. Fearing a revolt by his own militants, Mussolini decided to drop all trappings of democracy.[9]

On 3 January 1925, Mussolini made a truculent speech before the Chamber in which he took responsibility for squadristi violence (though he did not mention the assassination of Matteotti).[10] This speech usually is taken as the beginning of the fascist dictatorship because it was followed by several laws restricting or canceling common democratic liberties, voted by the Parliament filled by two thirds of Fascists because of the Acerbo Law.

Parties and leaders

| Party | Ideology | Leader | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National List (LN) | Fascism, Italian nationalism | Benito Mussolini | |

| Italian People's Party (PPI) | Christian democracy, Popularism | Alcide De Gasperi | |

| United Socialist Party (PSU) | Social democracy, Anti-fascism | Giacomo Matteotti | |

| Italian Socialist Party (PSI) | Socialism, Revolutionary socialism | Tito Oro Nobili | |

| Communist Party of Italy (PCdI) | Communism, Marxism-Leninism | Antonio Gramsci | |

| Italian Liberal Party (PLI) | Liberalism, Centrism | Luigi Facta | |

| Democratic Liberal Party (PLD) | Radicalism, Progressivism | Francesco Saverio Nitti | |

| Italian Republican Party (PRI) | Republicanism, Radicalism | Eugenio Chiesa | |

Results

| |||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National List | 4,305,936 | 60.09 | 355 | +250 | |

| Italian People's Party | 645,789 | 9.01 | 39 | −69 | |

| United Socialist Party | 422,957 | 5.90 | 24 | New | |

| Italian Socialist Party | 360,694 | 5.03 | 22 | −101 | |

| National List bis | 347,552 | 4.85 | 19 | New | |

| Communist Party of Italy | 268,191 | 3.74 | 19 | +4 | |

| Italian Liberal Party | 233,521 | 3.27 | 15 | −28 | |

| Democratic Liberal Party | 157,932 | 2.20 | 14 | −54 | |

| Italian Republican Party | 133,714 | 1.87 | 7 | +1 | |

| Italian Social Democratic Party | 111,035 | 1.55 | 10 | −19 | |

| Party of Italian Peasants | 73,569 | 1.03 | 4 | New | |

| Slavs and Germans | 62,491 | 0.87 | 4 | −5 | |

| Sardinian Action Party | 24,059 | 0.34 | 2 | New | |

| Dissident Fascists | 18,062 | 0.25 | 1 | New | |

| Invalid/blank votes | 448,949 | – | – | – | |

| Total | 7,614,451 | 100 | 535 | ±0 | |

| Registered voters/turnout | 11,939,452 | 63.8 | – | – | |

Results by Region

| Region | First party | Second party | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abruzzo-Molise | LN | PSU | PLD | |||

| Apulia | LN | PLI | PCdI | |||

| Basilicata | LN | PLD | PSDI | |||

| Calabria | LN | PLD | PSDI | |||

| Campania | LN | PLD | PSU | |||

| Emilia-Romagna | LN | PPI | PSU | |||

| Lazio | LN | PPI | PSI | |||

| Liguria | LN | PSU | PPI | |||

| Lombardy | LN | PPI | PSU | |||

| Marche | LN | PPI | PSU | |||

| Piedmont | LN | PLI | PSU | |||

| Sardinia | LN | PSdAz | PPI | |||

| Sicily | LN | PSDI | PLD | |||

| Trentino | LN | PPI | SeT | |||

| Tuscany | LN | PSU | PPI | |||

| Umbria | LN | PPI | PSI | |||

| Veneto | LN | PPI | PSI | |||

| Venezia Giulia | LN | PPI | SeT | |||

References

- ↑ Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p1047 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- 1 2 Nohlen & Stöver, p1033

- ↑ Boffa, Federico (2004-02-01). "Italy and the Antitrust Law: an Efficient Delay?" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ Carsten (1982), p.62

- ↑ Chiapello (2012), p.123

- ↑ Carsten (1982), p.64

- ↑ Carsten (1982), p.76

- ↑ Speech of 30 May 1924

- ↑ Paxton, Robert (2004). The Anatomy of Fascism. New York City: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4094-9.

- ↑ Mussolini, Benito. "discorso sul delitto Matteotti". wikisource.it. Retrieved 24 June 2013.