Jimmie Nicol

| Jimmie Nicol | |

|---|---|

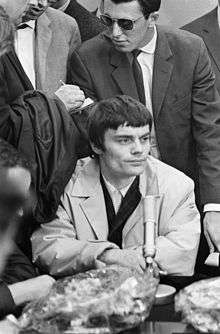

Jimmie Nicol at a 1964 Beatles press conference in the Netherlands | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | James George Nicol |

| Born |

3 August 1939 London, England, UK |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) | Drummer, business entrepreneur |

| Instruments | |

| Years active | 1950s-1960s |

| Associated acts | The Beatles, Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, Colin Hicks & The Cabin Boys, Vince Eager, Oscar Rabin, Cyril Stapleton, The Spotnicks, Charlie Katz, Ray McVay, The Shubdubs |

James George Nicol (born 3 August 1939), better known as Jimmie Nicol or Jimmy Nicol, is a British drummer and business entrepreneur. He is best known for temporarily replacing Ringo Starr in The Beatles for a series of concerts during the height of Beatlemania in 1964, elevating him from relative obscurity to worldwide fame and then back again in the space of a fortnight.[1] Nicol had hoped that his association with The Beatles would greatly boost his career but instead found that the spotlight moved away from him once Starr returned to the group. His subsequent lack of commercial success led him into bankruptcy in 1965. After then working with a number of different bands, including a successful stint with The Spotnicks, he left the music business in 1967 to pursue a variety of entrepreneurial ventures. Over the decades, Nicol has increasingly shied away from media attention, preferring not to discuss his connection to The Beatles nor seek financial gain from it. He has a son, Howard, who is a BAFTA award-winning sound engineer.

Early career

Jimmie Nicol's first professional career break came when he was talent spotted by Larry Parnes whilst drumming with various bands in London's The 2i's Coffee Bar in 1957, a time that saw Britain's skiffle-dominated music scene giving way to rock and roll which was being popularised by its Teddy Boy youth. Parnes then invited Nicol to join Colin Hicks & The Cabin Boys whom Parnes co-managed with John Kennedy (Colin Hicks is the younger brother of English entertainer Tommy Steele, whom Parnes also managed). After taking a temporary break playing as part of the original pit band in the Lionel Bart musical Fings Ain't Wot They Used T'Be at the Theatre Royal Stratford East Nicol rejoined Hicks's band for their appearance in the 1958 Italian film documentary Europa Di Notte, breaking them in Italy and subsequently allowing them to tour there extensively.[2] During the early sixties, Nicol went on to play for a number of artists, including Vince Eager, Oscar Rabin, and Cyril Stapleton. He was kept in regular work through Charlie Katz, a well-known session fixer during that period. Nicol has cited drummer Phil Seamen and saxophonist Julian "Cannonball" Adderley as being his main influences.[3]

In 1964 Nicol helped to form The Shubdubs with former Merseybeats bassist Bob Garner, a jazz line-up similar in musical style to Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, a group with whom Nicol had sat-in when they were the resident house band at London's now defunct Flamingo Jazz Club. Other members of The Shubdubs were Tony Allen (vocals), Johnny Harris (trumpet), Quincy Davis (tenor saxophone), and Roger Coulam (organ – went on to form Blue Mink). It was at this point that he received a telephone call from The Beatles' producer, George Martin. Nicol recalled: "I was having a bit of a lie down after lunch when the phone rang."[4]

With The Beatles

When Ringo Starr collapsed with tonsillitis and was hospitalised on 3 June 1964, the eve of The Beatles' 1964 Australasian tour, the band's manager Brian Epstein and their producer George Martin urgently discussed the feasibility of using a stand-in drummer rather than cancelling part of the tour. Martin suggested Jimmie Nicol as he had recently used him on a recording session with Tommy Quickly.[4] Nicol had also drummed on a 'Top Six' budget label album as part of an uncredited session band, as well as an extended play single (with three tracks on each side) of Beatles cover versions (marketed as 'Teenagers Choice' and entitled Beatlemania) which meant that he already knew the songs and their arrangements. Producer Bill Wellings and the aforementioned Shubdubs trumpeter Johnny Harris (freelancing here as an arranger and composer) were responsible for putting together alternative budget cover versions of songs taken from the British Hit Parade aimed at cash-strapped teenagers. Harris said: 'The idea was for me to try and guess which six songs would be topping the charts about a month ahead. I would do the arrangements and then go into the studio and record "sound a-likes"; the first EP (extended play) released got to number 30 in the charts. Jimmie was on drums and, as you can imagine, we covered a lot of the Beatles' songs.'[5] Although John Lennon and Paul McCartney quickly accepted the idea of using an understudy George Harrison threatened to pull out of the tour telling Epstein and Martin: 'If Ringo's not going, then neither am I. You can find two replacements.'[6] Martin recalled: 'They nearly didn't do the Australia tour. George is a very loyal person. It took all of Brian's and my persuasion to tell George that if he didn’t do it he was letting everybody down.'[7] Tony Barrow, who was The Beatles' press officer at the time, later commented: 'Brian saw it as the lesser of two evils; cancel the tour and upset thousands of fans or continue and upset the Beatles.'[8] Ringo: 'It was very strange, them going off without me. They’d taken Jimmie Nicol and I thought they didn’t love me any more – all that stuff went through my head.'[7] The arrangements were made very quickly, from a telephone call to Nicol at his home in West London inviting him to attend an audition-rehearsal at Abbey Road Studios,[9] to packing his bags, all in the same day.[10] At a press conference a reporter mischievously asked John Lennon why Pete Best, who had been The Beatles' previous drummer for two years but dismissed by the group on the eve of stardom, was not being given the opportunity of replacing Ringo, to which Lennon replied: 'He's got his own group [Pete Best & the All Stars], and it might have looked as if we were taking him back, which is not good for him.'[11] Later, on the subject of remuneration, Nicol recalled: 'When Brian [Epstein] talked of money in front of them [Lennon, McCartney and Harrison] I got very, very nervous. They paid me £2,500 per gig and a £2,500 signing bonus. Now, that floored me. When John spoke up in a protest by saying "Good God, Brian, you'll make the chap crazy!", I thought it was over. But no sooner had he said that when he said, 'Give him ten thousand!' Everyone laughed and I felt a hell of a lot better. That night I couldn't sleep a wink. I was a fucking Beatle!' These sums of money, which were vast in 1964, are unverified.

_1964_001.png)

Nicol's first concert with The Beatles took place just 27 hours later on 4 June at the KB Hallen in Copenhagen, Denmark. He was given the distinctive Beatle moptop hairstyle, put on Ringo's suit and went on stage to an audience of 4,500 Beatles fans. McCartney recalled: 'He was sitting up on this rostrum just eyeing up all the women. We'd start "She Loves You": [counting in] "one, two", nothing, "one, two", and still nothing!' Their set was reduced from eleven songs to ten, dropping Ringo's vocal spot of "I Wanna Be Your Man".[8] McCartney teasingly sent Starr a telegram saying: 'Hurry up and get well Ringo, Jimmy is wearing out all your suits.'[4] Commenting later on the fickle nature of his brief celebrity, Nicol reflected: 'The day before I was a Beatle, girls weren't interested in me at all. The day after, with the suit and the Beatle cut, riding in the back of the limo with John and Paul, they were dying to get a touch of me. It was very strange and quite scary.' He was also able to shed some light on how they passed the time between shows: 'I thought I could drink and lay women with the best of them until I caught up with these guys.'[12]

In the Netherlands, Nicol and Lennon allegedly spent a whole night at a brothel.[8] Lennon said: 'It was some kind of scene on the road. Satyricon! There's photographs of me grovelling about, crawling about Amsterdam on my knees, coming out of whore houses, and people saying "Good morning John". The police escorted me to these places because they never wanted a big scandal. When we hit town, we hit it – we were not pissing about. We had [the women]. They were great. We didn't call them groupies, then; I've forgotten what we called them, something like "slags".'[12][7] By then, The Beatles were becoming more restricted by their increasing fame, spending most of their free time inside hotel suites. But Nicol discovered that, beyond acting as a Beatle, he could behave much as any tourist could: 'I often went out alone. Hardly anybody recognised me and I was able to wander around. In Hong Kong, I went to see the thousands of people who live on little boats in the harbour. I saw the refugees in Kowloon, and I visited a nightclub. I like to see life. A Beatle could never really do that.'[13]

Nicol played a total of eight shows until Starr rejoined the group in Melbourne, Australia, on 14 June. He was unable to say 'goodbye' to The Beatles as they were still asleep when he left, and he did not want to disturb them. At Melbourne airport, Epstein presented him with a cheque for £500 and a gold Eterna-matic wrist watch inscribed: 'From The Beatles and Brian Epstein to Jimmy – with appreciation and gratitude.'[4] Martin later paid tribute to Nicol whilst acknowledging the problems he experienced in trying to re-adjust to a normal life again: 'Jimmie Nicol was a very good drummer who came along and learnt Ringo's parts very well. He did the job excellently, and faded into obscurity immediately afterwards.'[7] McCartney: 'It wasn't an easy thing for Jimmy to stand in for Ringo, and have all that fame thrust upon him. And the minute his tenure was over, he wasn't famous any more.' Nicol himself expressed his disillusionment several years later: 'Standing in for Ringo was the worst thing that ever happened to me. Until then I was quite happy earning £30 or £40 a week. After the headlines died, I began dying too.'[8] He resisted the temptation to sell his story, stating in a rare 1987 interview: 'After the money ran low, I thought of cashing-in in some way or other. But the timing wasn't right. And I didn't want to step on The Beatles' toes. They had been damn good for me and to me.'

Later career and life

Nicol reformed the Shubdubs, renaming themselves Jimmy Nicol and the Shubdubs. They released two singles "Husky"/"Don't Come Back", followed by "Humpty Dumpty"/"Night Train"; neither of which was a commercial success. He was later called upon again to stand in for an ailing drummer when Dave Clark of The Dave Clark Five fell ill, replacing him in the band for a season in Blackpool, Lancashire.[4] Whilst there Nicol was reminded of just how popular, albeit briefly, he had been as a stand-in Beatle; receiving a bundle of 5,000 fan letters passed on to him from an Australian radio disc jockey. Nicol sent a message back thanking the fans, promising that he would one day return to Australia permanently.[4] He was later reunited with The Beatles when his band was set down on the same bill as them and The Fourmost on 12 July 1964 at the Hippodrome in Brighton. In 1965 Nicol declared bankruptcy with debts of £4,066, nine months after being a temporary Beatle.[8] Later that year he joined the successful Swedish group The Spotnicks, recording with them and twice touring the world. He left them in 1967, spending time in Mexico studying samba and bossa nova rhythms, whilst also diversifying into business. In 1975 he returned to England and became involved with housing renovations. In 1988 it was rumoured that Nicol had died,[3] but an article in 2005 by the Daily Mail confirmed that he was still alive and living in London.

Legacy

During Nicol's brief time with the Beatles both Lennon and McCartney would often ask him how he felt he was coping to which his reply would usually be "It's getting better". Three years later McCartney was walking his dog, Martha, with Hunter Davies, the Beatles official biographer, when the sun came out. McCartney remarked that the weather was "getting better" and began to laugh, remembering Nicol. This event inspired the song "Getting Better" on 1967's Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[14] McCartney again makes reference to Nicol on the Let It Be tapes from 1969, saying: "I think you'll find we're not going abroad 'cause Ringo just said he doesn't want to go abroad. You know, he put his foot down. Although Jimmie Nicol might go abroad."

While appearing on the radio show "Fresh Air" hosted by Terry Gross in April 2016, Tom Hanks noted that he was at least partly influenced by Jimmie Nicol's experience with the Beatles when he wrote the script for his 1996 feature film That Thing You Do.

Discography and performance history

| 1950s |

| |

|---|---|---|

| 1957/1958 | Colin Hicks & The Cabin Boys. (Colin Hicks is the younger brother of British rock 'n' roll star Tommy Steele).

| |

| 1959/1960 | Vince Eager and the Quiet Three. | |

| 1960 | Oscar Rabin Band. | |

| 1961 | Cyril Stapleton Big Band. | |

| 1961–1963 | Session work (including jobs with musicians from the orchestras of Ted Heath and Johnny Dankworth). | |

| 1964 | The Shubdubs.

| |

| 1964 | April / May | Touring with Georgie Fame and The Blue Flames. |

| 1964 | June | The Beatles (as temporary stand in for Ringo Starr).

|

| 1964/1965 | Touring as: Jimmy Nicol & The Shubdubs

| |

| 1965–1967 | The Spotnicks.

| |

| 1967 | Nicol lived in Mexico working with samba & bossa nova groups. He married and had a son, Howard, who in the 1990s won an award for his work as sound engineer on a BBC collection of Beatles recordings. | |

| 1969 | Jimmie Nicol Show:

| |

| 1971 | Blue Rain (Mexican rock group recording in Nicol's house). | |

Information compiled from Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

See also

Notes

- ↑ He used the spelling "Jimmie Nicol" on his own bass drum. See the Jimmie Nicol page from pmouse.nl at the Wayback Machine (archived 11 January 2012)

- ↑ Norman 2009, pp. 180.

- 1 2 pmouse.nl 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Harry 1992, pp. 484.

- ↑ Darren Stuart 2012.

- ↑ Badman 2000, pp. 101.

- 1 2 3 4 The Beatles 2000, pp. 139.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mojo 2002, pp. 108.

- ↑ Harry 1992, pp. 45.

- ↑ Norman 1993, pp. 231.

- ↑ Badman 2000, pp. 103.

- 1 2 Q 2010, pp. 56.

- ↑ Badman 2000, pp. 110.

- ↑ Miles 1998, pp. 313.

Further reading

- Norman, Philip (2009). John Lennon. London: Harper. ISBN 978-0-00-719742-2.

- Badman, Keith (2000). The Beatles Off The Record.

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 0-304-35605-0.

- Harry, Bill (1992). The Ultimate Beatles Encyclopedia. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 0-86369-681-3.

- Stuart, Darren (2002). Johnny Harris – Movements CD & 2LP. London: Warner Bros.

- Miles, Barry (1998). Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now. London: Vintage. ISBN 0-7493-8658-4.

- "Special Limited Edition # M-04951". Mojo. 2002.

- Norman, Philip (1993). Shout!. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-017410-9.

- "Collectors Limited Edition". Q. 2010.

- Baker, Glenn A. (1983). The Beatles down under : the 1964 Australia & New Zealand tour. Sydney: Wild & Woolley.

- The Beatle Who Vanished by Jim Berkenstadt; Publisher: Rock and Roll Detective LLC (2013); ISBN 0985667702

External links

- "Jimmie Nicol". pmouse.nl. 2010. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012.

- Jimmie Nicol discography at Discogs

- Biography at feenotes.com