Murder of Kitty Genovese

Coordinates: 40°42′33.98″N 73°49′48.76″W / 40.7094389°N 73.8302111°W

| Kitty Genovese | |

|---|---|

|

Genovese in 1961 | |

| Born |

Catherine Susan Genovese July 7, 1935 Brooklyn, New York City, New York,[1] United States |

| Died |

March 13, 1964 (aged 28) Kew Gardens, Queens, New York City, New York,[2] United States |

| Cause of death | Stabbing |

| Resting place | Lakeview Cemetery, New Canaan, Connecticut, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Prospect Heights High School |

| Occupation | Bar manager |

| Employer | Ev's Eleventh Hour Club, Hollis, Queens, New York City, New York, United States |

| Known for | Supposed indifference by witnesses depicted in The New York Times article about her murder |

| Partner(s) | Mary Ann Zielonko |

Catherine Susan "Kitty" Genovese (July 7, 1935[1] – March 13, 1964) was an American woman who was stabbed to death outside her apartment building in Kew Gardens, a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Queens, on March 13, 1964.[3]

Two weeks after printing a short article on the attack, The New York Times published a longer report that conveyed a scene of indifference from neighbors who failed to come to Genovese's aid, claiming 37 or 38 witnesses saw or heard the attack and did not call the police. The incident prompted inquiries into what became known as the bystander effect or "Genovese syndrome".[4] Some researchers have questioned this version of events, offering alternative explanations as to why neighbors failed to intervene, and suggesting that the actual number of witnesses was far fewer than reported. In 2015, Genovese's younger brother Bill said that the police were indeed summoned twice but did not respond because they believed it was a domestic dispute, and blames The New York Times for faulty reporting.[5]

After the death of the perpetrator in 2016, The New York Times called the second story "flawed", adding:[6]

While there was no question that the attack occurred, and that some neighbors ignored cries for help, the portrayal of 38 witnesses as fully aware and unresponsive was erroneous. The article grossly exaggerated the number of witnesses and what they had perceived. None saw the attack in its entirety. Only a few had glimpsed parts of it, or recognized the cries for help. Many thought they had heard lovers or drunks quarreling. There were two attacks, not three. And afterward, two people did call the police. A 70-year-old woman ventured out and cradled the dying victim in her arms until they arrived. Ms. Genovese died on the way to a hospital.

Bill Genovese's 2015 film "The Witness" showed an interview with neighbor Sophia Farrar, who was around Kitty's age; Farrar explained in the film that she ran down to the stairwell when she heard her friend's screams, and held her as she was dying. Genovese's attacker, Manhattan native[6] Winston Moseley, was arrested during a house burglary several days after the attack; and he confessed to the murder while in custody, along with the murders and sexual assaults of two other women. At his trial, he was found guilty and sentenced to be executed, which was later reduced to life imprisonment. He died in prison on March 28, 2016, at the age of 81.

Personal life

Genovese was born on July 7, 1935, in New York City, the eldest of five children of Italian American parents Rachel (née Giordano) and Vincent Andronelle Genovese.[7][8] She was raised Catholic, living in a brownstone home at 29 St. Johns Place in Park Slope, a western Brooklyn neighborhood populated mainly by families of Italian heritage. As a teenager, she attended the all-girl Prospect Heights High School, where Genovese was recalled as being remarkably self-assured for her age and having a sunny disposition.[9] After Rachel witnessed a murder, the family moved to New Canaan, Connecticut, in 1954; however, Genovese, a recent high school graduate, remained in the city with her grandparents to prepare for her upcoming marriage ceremony. Late in the same year, the couple wed as planned, but the brief union was annulled before the end of 1954.[9]

Moving into an apartment in Brooklyn, Genovese worked in clerical jobs, which she found unappealing. By the late 1950s, she accepted a job as a bartender; at the time prior to her murder Genovese was working as a bar manager at Ev's Eleventh Hour Bar on Jamaica Avenue and 193rd Street in Hollis, Queens. She shared her Kew Gardens apartment at 82-70 Austin Street with her romantic partner, Mary Ann Zielonko, who Genovese met in 1963.[10][11]

Attack

In the early morning of March 13, 1964, at approximately 2:30 a.m., Genovese had left her job, and began driving home in her red Fiat. While waiting for a traffic light to change on Hoover Avenue, Genovese was observed by Moseley, who was parked in his car. Followed closely by Moseley, Genovese arrived home around 3:15 a.m., and had parked her car in the Kew Gardens Station Long Island Rail Road parking lot.[12] It was about 100 feet (30 m) from her apartment's door, located in an alleyway at the rear of the building. As she walked toward the apartment complex, Moseley[2] exited his vehicle, which was located at a corner bus stop on Austin Street, and approached Genovese armed with a hunting knife.[12] Frightened, Genovese began to run across the parking lot and toward the front of her building located at 82-70 Austin Street, trying to make it up to the corner toward the major thoroughfare of Lefferts Boulevard, Moseley ran after her, quickly overtook her, and stabbed her twice in the back. When later confessing, Moseley said that his motive for the attack was simply "to kill a woman". Genovese screamed, "Oh my God, he stabbed me! Help me!" Several neighbors heard her cry but, on a cold night with the windows closed, only a few of them recognized the sound as a cry for help. When Robert Mozer, one of the neighbors, shouted at the attacker "Let that girl alone!"[13] Moseley ran away and Genovese slowly made her way toward the rear entrance of her apartment building.[14] She was seriously injured, but now out of view of any witnesses.[13]

Records of the earliest calls to police are unclear and were not given a high priority by the police. One witness said his father called police after the initial attack and reported that a woman was "beat up, but got up and was staggering around".[15]

Other witnesses observed Moseley enter his car and drive away, only to return ten minutes later. In his car, he changed to a wide-brimmed hat to shadow his face. He systematically searched the parking lot, train station, and an apartment complex. Eventually, he found Genovese, who was lying, barely conscious, in a hallway at the back of the building where a locked doorway had prevented her from entering the building.[16] Out of view of the street and of those who may have heard or seen any sign of the original attack, Moseley stabbed Genovese several more times. Knife wounds in her hands suggested that she attempted to defend herself from him. While Genovese lay dying, Moseley raped her. He stole about $49 from her and left her in the hallway.[13] The attacks spanned approximately half an hour. Afterwards, "Genovese, still alive, lay in the arms of a neighbor named Sophia Farrar, who had courageously left her apartment to go to the crime scene, even though she had no way of knowing that [Moseley] had fled."[17]

A few minutes after the final attack, a witness, Karl Ross, called the police. Police arrived within minutes of Ross's call. Genovese was taken away by ambulance at 4:15 a.m. and died en route to the hospital. She was buried in a family grave at Lakeview Cemetery in New Canaan, Connecticut.[18]

Later investigation by police and prosecutors revealed that approximately a dozen (but almost certainly not the 38 cited in the Times article) individuals nearby had heard or observed portions of the attack, though none saw or was aware of the entire incident.[19] Only one witness, Joseph Fink, was aware she was stabbed in the first attack, and only Karl Ross was aware of it in the second attack. Many were entirely unaware that an assault or homicide was in progress; some thought what they saw or heard was a lovers' quarrel, a drunken brawl, or a group of friends leaving the bar when Moseley first approached Genovese.[14]

Perpetrator

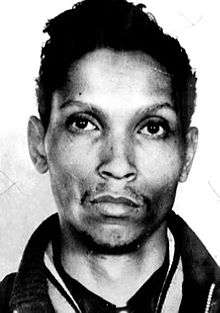

| Winston Moseley | |

|---|---|

Booking photograph (April 1, 1964) | |

| Born |

March 2, 1935[20] United States |

| Died |

March 28, 2016 (age 81)[6] Clinton Correctional Facility, Clinton County, New York, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Remington Rand machine operator |

| Criminal charge |

Murder A1 (degree-less prior to September 1, 1974, in the State of New York) Robbery (second degree) Attempted kidnapping (second degree) |

| Criminal penalty | Death reduced to life imprisonment plus two 15-year sentences |

| Conviction(s) | Murder |

Winston Moseley (March 2, 1935 – March 28, 2016) was at the time a 29-year-old man from South Ozone Park, Queens;[21] he was apprehended by police during a house burglary six days after Genovese's murder. At the time of his arrest, Moseley was working as a "Remington Rand tab operator", had no prior criminal record, and was married with three children.[22]

While in custody, Moseley confessed to killing Genovese. He detailed the attack, corroborating the physical evidence at the scene. Moseley said he preferred to kill women because: "they were easier and didn't fight back". Moseley stated that he got up that night around 2 a.m., leaving his wife asleep at home, and drove around to find a victim. He spied Genovese and followed her to the parking lot.[23] He also confessed to murdering and sexually assaulting two other women and to committing "30 to 40" burglaries.[24] Subsequent psychiatric examinations suggested that Moseley was a necrophile.[25][26]

Moseley committed another series of crimes when he escaped from custody on March 18, 1968, for which he received two additional 15-year sentences. He died in prison in 2016,[6] having been one of the longest serving inmates in the New York State prison system.[27]

Trial

Moseley's trial began on June 8, 1964, presided over by Judge J. Irwin Shapiro. Moseley initially pleaded not guilty, but his attorney later changed Moseley's plea to not guilty by reason of insanity.[28] On June 11, Moseley's attorney called him to testify in hopes that Moseley's testimony would convince the jury that he was "a schizophrenic personality and legally insane". During his testimony, Moseley described the events on the night he murdered Genovese, along with the two other murders to which he had confessed and numerous other burglaries and rapes. The jury deliberated for seven hours before returning a guilty verdict on June 11 around 10:30 p.m.[20]

On June 15, Moseley received the death sentence for the murder of Genovese. When the jury foreman read the sentence, Moseley showed no emotion, while some spectators applauded and others cheered. When calm had returned, Judge Shapiro added, "I don't believe in capital punishment, but when I see a monster like this, I wouldn't hesitate to pull the switch myself."[29] On June 1, 1967, the New York Court of Appeals found that Moseley should have been able to argue that he was "medically insane" at the sentencing hearing when the trial court found that he had been legally sane, and the initial death sentence was reduced to lifetime imprisonment.[30]

Imprisonment and death

On March 18, 1968, Moseley escaped from custody while being transported back to prison from Meyer Memorial Hospital in Buffalo, New York, where he had undergone minor surgery for a self-inflicted injury.[31][32] Moseley hit the transporting correctional officer, stole his weapon, and then fled to a nearby vacant house owned by a Grand Island, New York, couple, Mr. and Mrs. Matthew Kulaga. Moseley stayed at the residence undetected for three days. On March 21, the Kulagas went to check on the house, where they encountered Moseley. He held the couple hostage for more than an hour, during which he bound and gagged Matthew Kulaga and proceeded to rape Mrs. Kulaga. He then took the couple's car and fled.[31][33] Moseley made his way to Grand Island where, on March 22, he broke into another house and took a woman and her daughter hostage. He held them hostage for two hours before releasing them unharmed. Moseley surrendered to police shortly thereafter.[34] He was later charged with escape and kidnapping, to which he pleaded guilty. Moseley was given two additional fifteen-year sentences concurrent with his life sentence.[35]

During the 1970s, Moseley participated in the Attica Prison riot,[36] and late in the decade obtained a Bachelor of Arts in sociology in prison from Niagara University.[37]

Moseley became eligible for parole in 1984. During his first parole hearing, Moseley told the parole board that the notoriety he faced due to his crimes made him a victim also, stating, "For a victim outside, it's a one-time or one-hour or one-minute affair, but for the person who's caught, it's forever."[38] At the same hearing, Moseley claimed he never intended to kill Genovese and that he considered her murder to be a mugging because "[...] people do kill people when they mug them sometimes." The board denied his request for parole.[39]

Moseley returned for a parole hearing on March 13, 2008, the 44th anniversary of Genovese's murder. The previous week, Moseley had turned 73 years old, and had still shown little remorse for murdering Genovese.[38] Parole was denied.[40] Genovese's brother Vincent was unaware of the 2008 hearing until he was contacted by New York Daily News reporters.[38] Vincent Genovese has reportedly never "recovered from the horror" of his sister's murder.[38] "This brings back what happened to her", Vincent had said; "the whole family remembers".[38]

Moseley was denied parole an eighteenth time in November 2015.[41] He died in prison on March 28, 2016, at the age of 81.[6]

Reaction

Public reaction

At first, the murder of Genovese did not receive much media attention. It took a remark from the New York City Police Commissioner Michael J. Murphy to New York Times metropolitan editor A. M. Rosenthal over lunch – Rosenthal later quoted Murphy as saying, "That Queens story is one for the books" – to provoke the Times into publishing an investigative report.[7][17]

The article,[21][42] written by Martin Gansberg and published on March 27, 1964, two weeks after the murder, bore the headline "37 Who Saw Murder Didn't Call the Police". (It has been variously quoted and reproduced since 1964 with a headline that begins "Thirty-Eight Who Saw..."[43]) The public view of the story crystallized around a quote from the article by an unidentified neighbor who saw part of the attack but deliberated before finally getting another neighbor to call the police, saying, "I didn't want to get involved."[7] Many then saw the story of Genovese's murder as emblematic of the callousness or apathy of life in big cities, and New York in particular.[43]

Science-fiction author and cultural provocateur Harlan Ellison, in articles published in 1970 and 1971 in the Los Angeles Free Press and in Rolling Stone, referred to the witnesses as "thirty-six motherfuckers"[44] and stated that they "stood by and watched" Genovese "get knifed to death right in front of them, and wouldn't make a move"[45] and that "thirty-eight people watched" Genovese "get knifed to death in a New York street".[46] In an article in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (June 1988) and later reprinted in his book Harlan Ellison's Watching, Ellison referred to the murder as "witnessed by thirty-eight neighbors, not one of whom made the slightest effort to save her, to scream at the killer, or even to call the police." He cited reports he claimed to have read that one man, "viewing the murder from his third-floor apartment window, stated later that he rushed to turned up his radio so he wouldn't hear the woman's screams." Ellison says that the reports attributed the "get involved" quote to nearly all of the 38 who supposedly witnessed the attack.[47]

More recent investigations have questioned the original version of events.[48][49][50] A 2007 study found many of the purported facts about the murder to be unfounded,[51] stating there was "no evidence for the presence of 38 witnesses, or that witnesses observed the murder, or that witnesses remained inactive".[52]

A 2004 article in the New York Times by Jim Rasenberger, published on the 40th anniversary of Genovese’s murder, raised numerous questions about claims in the original Times article. In 2007, a study found many of the purported facts about the murder to be unfounded.[53]

None of the witnesses observed the attacks in their entirety. Because of the layout of the complex and the fact that the attacks took place in different locations, no witness saw the entire sequence of events. Most only heard portions of the incident without realizing its seriousness, a few saw only small portions of the initial assault, and no witnesses directly saw the final attack and rape, in an exterior hallway.[1] After the initial attack punctured her lungs, leading to her eventual death from asphyxiation, it is unlikely that Genovese was able to scream at any volume.[54] Only one witness, Joseph Fink, was aware she was stabbed in the first attack, and only Karl Ross (the neighbor who called police) was aware of it in the second attack. Many were unaware that an assault or homicide was in progress; some thought that what they saw or heard was a lovers' quarrel, a drunken brawl, or a group of friends leaving the bar when Moseley first approached Genovese.[14]

Public reaction to murders happening in the neighborhood supposedly did not change. According to a The New York Times article dated December 28, 1974, ten years after Genovese's murder, 25-year-old Sandra Zahler was beaten to death early Christmas morning in an apartment within a building that overlooked the site of the Genovese attack. Neighbors again said they heard screams and "fierce struggles" but did nothing.[55]

In an interview on NPR on March 3, 2014, Kevin Cook, author of Kitty Genovese: The Murder, the Bystanders, the Crime That Changed America, said:

Thirty-eight witnesses — that was the story that came from the police. And it really is what made the story stick. Over the course of many months of research, I wound up finding a document that was a collection of the first interviews. Oddly enough, there were 49 witnesses. I was puzzled by that until I added up the entries themselves. Some of them were interviews with two or three people [who] lived in the same apartment. I believe that some harried civil servant gave that number to the police commissioner who gave it to Rosenthal, and it entered the modern history of America after that.[56]

Psychological research

Harold Takooshian, writing in Psychology Today, stated that:

"In his book, Rosenthal asked a series of behavioral scientists to explain why people do or do not help a victim and, sadly, he found none could offer an evidence-based answer. How ironic that this same question was answered separately by a non-scientist. When the killer was apprehended, and Chief of Detectives Albert Seedman asked him how he dared to attack a woman in front of so many witnesses, the psychopath calmly replied, 'I knew they wouldn't do anything, people never do' (Seedman & Hellman, 1974, p. 100)".[57]

The apparent lack of reaction by numerous neighbors purported to have watched the scene or to have heard Genovese's cries for help, although erroneously reported, prompted research into diffusion of responsibility and the bystander effect. Social psychologists John M. Darley and Bibb Latané started this line of research, showing that contrary to common expectations, larger numbers of bystanders decrease the likelihood that someone will step forward and help a victim.[58] The reasons include the fact that onlookers see that others are not helping either, that onlookers believe others will know better how to help, and that onlookers feel uncertain about helping while others are watching. The Kitty Genovese case thus became a classic feature of social psychology textbooks.

In September 2007, the American Psychologist published an examination of the factual basis of coverage of the Kitty Genovese murder in psychology textbooks. The three authors concluded that the story is more parable than fact, largely because of inaccurate newspaper coverage at the time of the incident.[14] According to the authors, "despite this absence of evidence, the story continues to inhabit our introductory social psychology textbooks (and thus the minds of future social psychologists)." One interpretation of the parable is that the drama and ease of teaching the exaggerated story make it easier for professors to capture student attention and interest.[59]

Psychologist Frances Cherry has suggested the interpretation of the murder as an issue of bystander intervention is incomplete.[60] She has pointed to additional research such as that of Borofsky[61] and Shotland[62] demonstrating that people, especially at that time, were unlikely to intervene if they believed a man was attacking his wife or girlfriend. She has suggested that the issue might be better understood in terms of male/female power relations.[60]

In popular culture

The story of the witnesses who did nothing "is taught in every introduction-to-psychology textbook in the United States and Britain, and in many other countries ... and has been made popularly known through television programs and books,"[59] and even songs.

Film and television

- The Perry Mason episode, "The Case of the Silent Six" (November 21, 1965), portrays the brutal beating of a young woman whose screams for help are ignored by the six residents of her small apartment building. The "get involved" quote is spoken once by Paul Drake and paraphrased by several other characters.[63]

- An American television movie, Death Scream (1975), starring Raúl Juliá, was based on the murder.[64]

- In the season 1 Law & Order episode, "The Violence of Summer" (1991), Detective Logan remarks: "It is the post-Kitty Genovese era, nobody wants to look, they think they'll get involved", when lamenting the lack of witnesses to a rape.

- Season 6, episode 10 of Law & Order, "Remand" (1996), featuring a similar but non-fatal attack on a victim named Cookie Costello, is loosely based on the Genovese case.[65]

- Season 17, episode 13 Law & Order: SVU, "41 Witnesses" (2015), a woman is raped and among 41 witnesses nobody intervenes.

- The crime thriller film The Boondock Saints (1999) uses the incident as an example of good men doing nothing.

- History's Mysteries, episode 15.2 "Silent Witnesses: The Kitty Genovese Murder" (2006) on the History Channel, is a documentary of the murder.[66]

- The film 38 témoins (2012, 38 Witnesses), directed by Lucas Belvaux, is based on Didier Decoin's 2009 novel about the case and reset in Le Havre, France.

- Season 2, episode 3 of the Investigation Discovery Channel's A Crime to Remember series, "38 Witnesses" (2014), is about the Genovese murder.

- Season 5, episode 7 of Girls (2016), "Hello Kitty" follows the characters as they navigate through an interactive theatrical version of Genovese's murder.

- The 2015 film The Witness reexamines the murder with interviews of both Genovese's and her killer's families.[67]

- The 2016 film '37' is a drama and a fictional account of the night Kitty Genovese was murdered in 1964, Kew Gardens, Queens.

Literature

- A. M. Rosenthal's book, Thirty-Eight Witnesses: The Kitty Genovese Case (1964), explores the incident.[68]

- Genovese's murder inspired Harlan Ellison's short story "The Whimper of Whipped Dogs", first published in Bad Moon Rising: An Anthology of Political Forebodings (1973).[69]

- Dean Koontz's horror novel, Twilight Eyes (1985), refers to the murder as motivation for the main characters to take action.[70]

- Genovese's murder was a pivotal event in the comic series Watchmen (1986-1987), which originally inspired protagonist Rorschach to become a masked vigilante. His unique mask made from the signature "Moving Ink Blot" material was created from a dress that was originally intended for Genovese.[59][71]

- In his book, The Tipping Point (2000), Malcolm Gladwell refers to the case and the "bystander effect" as evidence of contextual cues for human responses.[59]

- Ryan David Jahn's novel Good Neighbors (2009) is based on the murder.[72][73]

- Didier Decoin's novel Est-ce ainsi que les femmes meurent? (2009; Is This How Women Die?) is based on the murder.

- SuperFreakonomics (2009), by Steven Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner, uses the murder of Genovese as a case study in the book's chapter on altruism.

- In Twisted Confessions: The True Story Behind the Kitty Genovese and Barbara Kralik Murder Trials, Charles Skoller, the lead prosecutor from the Genovese murder trial, recalls the events and mass attention surrounding the infamous crime.

- In 2016 the book "No One Helped": Kitty Genovese, New York City, and the Myth of Urban Apathy, by Marcia M. Gallo, won in the category of LGBT Nonfiction at the Lambda Literary Awards.[74][75]

- In Pat Conroy's novel The Lords of Discipline, the novel's protagonist, a senior cadet at a South Carolina military college, uses the Genovese case as an example to explain the military college's honor code to the incoming freshman class, repeating the mythology of the uninvolved bystanders,[76]

Music

- Genovese's murder inspired folk singer Phil Ochs to write the song "Outside of a Small Circle of Friends", originally released on the album Pleasures of the Harbor (1967). This song related five different situations that should demand action on the part of the narrator, but in each case the narrator concludes: "I'm sure it wouldn't interest anybody outside of a small circle of friends".[77][78]

- Joey Levine and Artie Resnick composed the song "All's Quiet On West 23rd" (1967), which tells the story of a fictional murder based upon the Genovese case. It was released on record by several musicians in 1967–1968, including The Jet Stream, sung by Levine; Julie Budd in the US; and Liza Strike in the UK.[79]

- Genovese is briefly mentioned in the song "Big Bird" by Andrew Jackson Jihad. The lyric is "I'm afraid of the social laziness that let Kitty Genovese die." In reference to something the songwriter (Sean Bonnette) is afraid of.

Theatre

- English composer Will Todd's music theatre work, The Screams of Kitty Genovese (1999), is based on the murder.

See also

- Crime in New York City

- Death of Cristina and Violetta Djeordsevic (Italy)

- Death of Wang Yue (China)

- Social loafing

- Volunteer's dilemma

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 Demay, Joseph. "Kitty Genovese". A Picture History of Kew Gardens, NY. Archived from the original on February 23, 2007. Retrieved March 12, 2007.

- 1 2 Jackson, Kenneth T (1995), The Encyclopedia of New York City, The New York Historical Society; Yale University Press, p. 458.

- ↑ "Queens Woman Is Stabbed to Death in Front of Home". The New York Times. March 14, 1964. p. 26. Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- ↑ Dowd, Maureen (March 12, 1984). "20 years after the murder of Kitty Genovese, The question remains: Why?". New York Times. p. B1. Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Brother of Kitty Genovese, the 28-year-old brutally raped and stabbed to death in New York City in 1964, says her screams for help were NOT ignored in the case that has became the 'poster crime' for bystander apathy", Daily mail.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McFadden, Robert D (April 4, 2016), "Winston Moseley, 81, Killer of Kitty Genovese, Dies in Prison", The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 Rasenberger, Jim (February 8, 2004). "Kitty, 40 Years Later". nytimes.com. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- ↑ Gado, Mark. "The Kitty Genovese Murder". trutv.com. p. 2. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- 1 2 Pelonero, Catherine (2014). Kitty Genovese: A True Account of a Public Murder and Its Private Consequences. Sky Horse Publishing. ISBN 9781634507554.

- ↑ "Remembering Kitty Genovese (Transcript)". Sound Portraits. NPR. March 13, 2004.

- ↑ Pearlman, Jeff. "Infamous '64 murder lives in heart of woman's `friend'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- 1 2 Skoller, Charles (2013). Twisted Confessions: The True Story Behind the Kitty Genovese and Barbara Kralik Murder Trials. Author House. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4817-4615-1.

- 1 2 3 Krajicek, David (March 13, 2011). "The killing of Kitty Genovese: 47 years later, still holds sway over New Yorkers". New York Daily News. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Manning, R.; Levine, M; Collins, A. (September 2007). "The Kitty Genovese murder and the social psychology of helping: The parable of the 38 witnesses". American Psychologist. 62 (6): 555–562. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.6.555. PMID 17874896.

- ↑ Rosenthal, A.M. (1964). Thirty-Eight Witnesses: The Kitty Genovese Case. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21527-3.

- ↑ "On This Day: NYC Woman Killed as Neighbors Look On". Finding Dulcinea. March 13, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- 1 2 Lemann, Nicholas (March 10, 2014). "What the Kitty Genovese Story Really Means". The New Yorker.

- ↑ Gansberg, Martin (March 12, 1965). "Yes, Witnesses Report; Neighbors Have Doubts; Murder Street: Would They Aid?". The New York Times. p. 35.

- ↑ Rasenberger, Jim (October 2006). "Nightmare on Austin Street". American Heritage. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- 1 2 Gado, p. 9

- 1 2 Gansberg, Martin (March 27, 1964). "37 Who Saw Murder Didn't Call the Police" (PDF). The New York Times.

- ↑ Kitty Genovese; A True Account of a Public Murder and its Private Consequences by Catherine Pelonero

- ↑ Aggrawal, p.144.

- ↑ Gado, p.5

- ↑ Aggrawal, Anil (2010). Necrophilia: Forensic and Medico-Legal Aspects. New York: CRC Press. pp. 143–147.

- ↑ "N.Y. Murder Case Unfolds". The News and Courier. June 25, 1964. pp. 9–B. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Moseley". The Star Ledger. March 12, 2013. p. 8.

- ↑ Gado, p.8

- ↑ "Court Applauds Death Sentence". The Windsor Star. June 16, 1964. p. 8. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- ↑ Maiorana, Ronald (June 2, 1967). "Genovese Slayer Wins Life Sentence in Appeal". New York Times.

- 1 2 "Killers' Terror Rampage Retold". The Evening News. December 3, 1969. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- ↑ Dwyer, Kevin; Fiorillo, Juré (2006). True Stories of Law & Order: The Real Crimes Behind the Best Episodes of the Hit TV Show. Penguin. p. 58. ISBN 0-425-21190-8.

- ↑ "Couple Is Held Captive By Escaped Murderer". Reading Eagle. March 21, 1968. p. 22. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Fugitive Killer Gives Up". Edmonton Journal. March 22, 1968. p. 5. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Genovese killer's parole denied". Lakeland Ledger. February 1, 1984. p. 10A. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- ↑ Barry, Dan (May 26, 2006). "Once Again, A Killer Makes His Pitch". New York Times. p. b1. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ↑ Gado, p.10

- 1 2 3 4 5 McShane, Larry (March 10, 2008). "Deny parole to '64 Kitty Genovese horror killer, says victim's brother". NY daily news. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ↑ Smith, Greg B. (August 5, 1995). "Kitty Killer: I'm victim too says notoriety causes him hurt". NY Daily News. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Moseley's prison records, accessible with DIN=64-A-0102 or by name". NYSDOccsLookup.

- ↑ Peltz, Jennifer (2015-11-17). "Kitty Genovese Killer Denied Parole in Notorious 1964 Case". Associated Press. WSB-TV. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- ↑ Gansberg, Martin (27 March 1964). "37 Who Saw Murder Didn't Call the Police". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- 1 2 Gansberg, Martin (March 27, 1964). "Thirty-Eight Who Saw Murder Didn't Call the Police". The New York Times. Southeastern. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ↑ Ellison, Harlan (1983). "62: May 1, 70". The Other Glass Teat. Ace. p. 61.

- ↑ Ellison, Harlan (1983). "92: January 8, 71". The Other Glass Teat. Ace. p. 333.

- ↑ Ellison, Harlan (1983). "100: March 26, 71". The Other Glass Teat. Ace. p. 383.

- ↑ Harlan Ellison, "Intallment 30 1/2: In Which Three Cinematic Variations on 'The Whimper of Whipped Dogs' Are Presented." In Harlan Ellison's Watching (Underwood-Miller, 1989), pp. 432-435.

- ↑ Dubner & Levitt (October 20, 2009). Superfreakonomics (First ed.). William Morrow.

- ↑ "Interview: Kevin Cook, Author Of 'Kitty Genovese'". NPR.org. Washington, DC: NPR. March 3, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- ↑ Lemann, Nicholas (March 10, 2014). "What the Kitty Genovese Story Really Means". The New Yorker. New York, NY: Condé Nast. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- ↑ Jarrett, Christian (October 23, 2007). "The truth behind the story of Kitty Genovese and the bystander effect". Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ Manning, Rachel; Levine, Mark; Collins, Alan (September 2008). "The Kitty Genovese Murder and the Social Psychology of Helping: the parable of the 38 witnesses". American Psychologist. American Psychological Association. 62 (6): 555. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.62.6.555. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ "A Call for Help". New Yorker. March 10, 2014.

- ↑ "The Witnesses That Didn't". On the Media. March 27, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

Brooke Gladstone: Wasn't she screaming during the second attack? Joseph de May: The wounds that she apparently suffered during the first attack, the two to four stabs in the back, caused her lungs to be punctured, and the testimony given at trial is that she died not from bleeding to death but from asphyxiation. The air from her lungs leaked into her thoracic cavity, compressing the lungs, making it impossible for her to breathe. I am not a doctor, but as a layman my question is, if someone suffers that type of lung damage, are they even physically capable of screaming for a solid half hour?

- ↑ McFadden, Robert D. (December 27, 1974). "A Model's Dying Screams Are Ignored At the Site of Kitty Genovese's Murder". New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ↑ "What Really Happened The Night Kitty Genovese Was Murdered?". NPR Books. March 3, 2014.

- ↑ Takooshian, Harold, Ph.D., "Not Just a Bystander: The 1964 Kitty Genovese Tragedy: What Have We Learned?", Psychology Today, March 24, 2014.

- ↑ Zimbardo, Philip. "Dr. Philip Zimbardo on the bystander effect and the murder of Kitty Genovese.". www.bystanderrevolution.org. Bystander Revolution. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Rentschler, Carrie (2010). "The Physiognomic Turn (Feature 231)". International Journal of Communication. 4.

- 1 2 Cherry, F. (1995) The Stubborn Particulars of Social Psychology: Essays on the research process, London, Routledge.

- ↑ Borofsky, G.; Stollak, G.; Messe, L. (1971). "Bystander reactions to physical assault: Sex differences in reactions to physical assault". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 7: 313–18. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(71)90031-x.

- ↑ Shotland, R. L.; Straw, M. K. (1976). "Bystander response to an assault: when a man attacks a woman". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 34: 990–9. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.34.5.990.

- ↑ "Perry Mason: The Case of the Silent Six". IMDb.

- ↑ Marill, Alvin H. (1980). Movies Made For Television (Reprint by arrangement with Arlington House Publishers ed.). New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc.

- ↑ Courrier, Kevin; Green, Susan (1999). Law & Order: The Unofficial Companion – Updated and Expanded (2 ed.). Macmillan. p. 253. ISBN 1-580-63108-8.

- ↑ "History's Mysteries Silent Witnesses: The Kitty Genovese Murder (TV Episode)". IMDb. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ↑ Hoffman, Jordan (September 29, 2015). "The Witness Review: Documentary Digs into Infamous Kitty Genovese Murder". Film. The Guardian. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Abe Rosenthal, Thirty-Eight Witnesses: The Kitty Genovese Case (California, Univ of California Press 1964), pp. xxvii-xxix - On1Foot". on1foot.org. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ↑ Ellison, Harlan (1975). "Introduction". No Doors, No Windows.

- ↑ Koontz, Dean R. (1985). Twilight Eyes. Berkley Books.

- ↑ Hughes, Jamie A. (August 2006). "Who Watches the Watchmen?: Ideology and 'Real World' Superheroes". The Journal of Popular Culture. 39 (4): 546–557. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5931.2006.00278.x.

- ↑ "Interview with Ryan David Jahn". Pan MacMillan.

- ↑ Crimesquad.com Book review of Acts of Violence, by David Jahn

- ↑ "Lambda Literary Awards Finalists Revealed: Carrie Brownstein, Hasan Namir, 'Fun Home' and Truman Capote Shortlisted".

- ↑ "Twitter". Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ↑ Conroy, Pat (2010-08-17). "9". The Lords of Discipline. Open Road Media. ISBN 9781453203989.

- ↑ Unterberger, Richie (2003). Eight Miles High: Folk-Rock's Flight from Haight-Ashbury to Woodstock. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. p. 94. ISBN 0-87930-743-9.

- ↑ Schumacher, Michael (1996). There But for Fortune: The Life of Phil Ochs. New York: Hyperion. p. 156. ISBN 0-7868-6084-7.

- ↑ "all's quiet on west 23rd - 45cat Search". 45cat.com. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

Bibliography

- Cook, Kevin (2014). Kitty Genovese: The Murder, The Bystanders, The Crime That Changed America. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-23928-7.

- Darley, John. "Bystander Intervention in Emergencies: Diffusion of Responsibility". Wadsworth.com.

- Gallo, Marcia M. (2015). "No One Helped": Kitty Genovese, New York City, and the Myth of Urban Apathy. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-5664-0.

- Ochs, Phil. "'Outside of a Small Circle of Friends' lyrics". CS.pdx.edu.

- Ozog, Matthew (Producer) & Isay, David (Executive Producer) & Ticktin, Jessica (Production Assistant). "Remembering Kitty Genovese". Sound Portraits. Includes interview with Mary Ann Zielonko and crime scene photographs.

- Pelonero, Catherine (2014). Kitty Genovese: A True Account of a Public Murder and its Private Consequences. Skyhorse Publishing. p. 376. ISBN 978-1-62873-706-6.

- Rosenthal, A.M. (1964). Thirty-Eight Witnesses: The Kitty Genovese Case. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21527-3.

- Seedman, Albert A. & Peter Hellman (2011). Chief!: Classic Cases from the Files of the Chief of Detectives (originally published 1974). Authors Guild backinprint.com. ISBN 1450279724.

- Skoller, Charles E. (2008). Twisted Confessions: The True Story Behind the Kitty Genovese and Barbara Kralik Murder Trials. Bridgeway Books. p. 228. ISBN 1-934454-17-6.

- "Winston Moseley's Confession" (PDF). Internet Archive. Archived from the original on February 18, 2004.

Further reading

- De May, Joseph, Jr. "Kitty Genovese: What you think you know about the case might not be true". A reinvestigation by a member of the Richmond Hill Historical Society. Richmond Hill, NY. This comes in two versions:

- Single page at the Wayback Machine (archived June 16, 2006) that analyzes and argues with Gansberg's article, with links to other material.

- A 13-page comprehensive summary at the Wayback Machine (archived February 7, 2004) of the same article.

- Getlen, Larry (February 16, 2014). "Debunking the Myth of Kitty Genovese". New York Post.

- Pelonero, Catherine (March 2, 2014). "The Truth About Kitty Genovese". New York Daily News.

- "Kitty Genovese, Revised". Wilson Quarterly. Winter 2007.