Konstantin Chernenko

| Konstantin Chernenko Константин Черненко | |

|---|---|

| |

| General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union | |

|

In office 13 February 1984 – 10 March 1985 | |

| Preceded by | Yuri Andropov |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Gorbachev |

| Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union | |

|

In office 11 April 1984 – 10 March 1985 | |

| Preceded by | Yuri Andropov |

| Succeeded by | Andrei Gromyko |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko 24 September 1911 Bolshaya Tes, Yeniseysk Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died |

10 March 1985 (aged 73) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Resting place | Kremlin Wall Necropolis, Moscow, Russian Federation |

| Citizenship | Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Spouse(s) |

Faina Vassilyevna Chernenko Anna Dmitrievna Lyubimova |

| Children |

Albert Chernenko Vera Chernenko Yelena Chernenko Vladimir Chernenko |

| Awards |

|

| Signature |

|

|

Central institution membership

Other political offices held

| |

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko (/tʃɜːrˈnɛŋkoʊ/;[1] Russian: Константи́н Усти́нович Черне́нко; IPA: [kənˈstɐntʲin ustʲinɐˈvʲɪtɕ tɕɨrˈnʲenkə], 24 September 1911 – 10 March 1985) was a Soviet politician and the fifth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He led the Soviet Union from 13 February 1984 until his death thirteen months later, on 10 March 1985. Chernenko was also Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet from 11 April 1984 until his death.

Early life and education

Chernenko was born to a poor family in the village of Bolshaya Tes (now in Novosyolovsky District, Krasnoyarsk Krai) on 24 September 1911.[2] His father, Ustin Demidovich (of Ukrainian origin), worked in copper and gold mines while his mother (of Jewish origin) took care of the farm work.

Chernenko joined the Komsomol (Communist Youth League) in 1929, and became a full member of the Communist Party in 1931. From 1930 to 1933, he served in the Soviet frontier guards on the Soviet-Chinese border. After completing his military service, he returned to Krasnoyarsk as a propagandist. In 1933 he worked in the Propaganda Department of the Novosyolovsky District Party Committee. A few years later he was promoted head of the same department in Uyarsk Raykom. Chernenko then steadily rose through the Party ranks, becoming the Director of the Krasnoyarsk House of Party Enlightenment then in 1939, the Deputy Head of the AgitProp Department of Krasnoyarsk Territorial Committee and finally, in 1941 he was appointed Secretary of the Territorial Party Committee for Propaganda. It was in the 1940s that Chernenko established a close relationship with Fyodor Kulakov.[3] In 1945, he acquired a diploma from a party training school in Moscow, and in 1953 he finished a correspondence course for schoolteachers.

The turning point in Chernenko’s career was his assignment in 1948 to head the Communist Party’s propaganda department in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. There, he met and won the confidence of Leonid Brezhnev, the first secretary of the Moldavian SSR from 1950 to 1952 and future leader of the Soviet Union. Chernenko followed Brezhnev in 1956 to fill a similar propaganda post in the CPSU Central Committee in Moscow. In 1960, after Brezhnev was named chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (titular head of state of the Soviet Union), Chernenko became his chief of staff.

Politburo career

In 1964 Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was deposed, and succeeded by Leonid Brezhnev. During Brezhnev's tenure as Party leader, Chernenko's career continued successfully. He was nominated in 1965 as head of the General Department of the Central Committee, and given the mandate to set the Politburo agenda, and prepare drafts of numerous Central Committee decrees and resolutions. He also monitored telephone and wiretapping devices in various offices of the top Party members. Another one of his jobs was to sign hundreds of Party documents daily, a job he did for the next 20 years. Even after he became General Secretary of the Party, he continued to sign papers referring to the General Department (when he could no longer physically sign documents, a facsimile was used instead).

In 1971 Chernenko was promoted to full membership in the Central Committee: Overseeing Party work over the Letter Bureau, dealing with correspondence. In 1976 he was elected secretary of the Letter Bureau. In 1977 he became Candidate, and in 1978 full member of the Politburo, serving second to the General Secretary in terms of Party hierarchy.

During Brezhnev's final years, Chernenko became fully immersed in ideological Party work: Heading Soviet delegations abroad, accompanying Brezhnev to important meetings and conferences, and working as a member of the commission that revised the Soviet Constitution in 1977. In 1979 he took part in the Vienna arms limitation talks.

After Brezhnev's death in November 1982, there was speculation that the position of General Secretary would fall to Chernenko, however he was unable to rally enough popular support for his candidacy within the Party, and the posting fell to former KGB chief Yuri Andropov.

Leader of the Soviet Union

Yuri Andropov died in February 1984, after just 15 months in office. Chernenko was then elected to replace Andropov, despite concerns over his own ailing health, and against Andropov's wishes (he stated he wanted Gorbachev to succeed him). Yegor Ligachev writes in his memoirs that Chernenko was elected general secretary without a hitch. At the Central Committee plenary session on 13 February 1984, four days after Andropov's death, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, Premier, and Politburo member Nikolai Tikhonov moved that Chernenko be elected general secretary, and the Committee duly voted him in.

Arkady Volsky, an aide to Andropov and other general secretaries, recounts an episode that occurred after a Politburo meeting on the day following Andropov's demise: As Politburo members filed out of the conference hall, either Andrei Gromyko or (in later accounts) Dmitriy Ustinov is said to have put his arm round Nikolai Tikhonov's shoulders and said: "It's okay, Kostya is an agreeable guy (pokladisty muzhik), one can do business with him...." The Politburo failed to pass the decision for Gorbachev, who was nominally Chernenko's second in command, to run the meetings of the Politburo itself in the absence of Chernenko; the latter due to his declining health, began to miss those meetings with increasing frequency. As Nikolai Ryzhkov describes it in his memoirs, "every Thursday morning he (Mikhail Gorbachev) would sit in his office like a little orphan – I would often be present at this sad procedure – nervously awaiting a telephone call from the sick Chernenko: Would he come to the Politburo himself or would he ask Gorbachev to stand in for him this time again?"

At Andropov's funeral, he could barely read the eulogy. Those present strained to catch the meaning of what he was trying to say in his eulogy. He spoke rapidly, swallowed his words, kept coughing and stopped repeatedly to wipe his lips and forehead. He ascended Lenin's Mausoleum by way of a newly installed escalator and descended with the help of two bodyguards.

Chernenko represented a return to the policies of the late Brezhnev era. Nevertheless, he supported a greater role for the labour unions, and reform in education and propaganda. The one major personnel change Chernenko made was the dismissal of the chief of the General Staff, Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov, who had advocated less spending on consumer goods in favor of greater expenditures on weapons research and development. Ogarkov was subsequently replaced by Marshal Sergey Akhromeyev.

In foreign policy, he negotiated a trade pact with the People's Republic of China. Despite calls for renewed détente, Chernenko did little to prevent the escalation of the Cold War with the United States. For example, in 1984, the Soviet Union prevented a visit to West Germany by East German leader Erich Honecker. However, in late autumn of 1984, the U.S. and the Soviet Union did agree to resume arms control talks in early 1985. In November 1984 Chernenko met with Britain's Labour Party leader, Neil Kinnock.

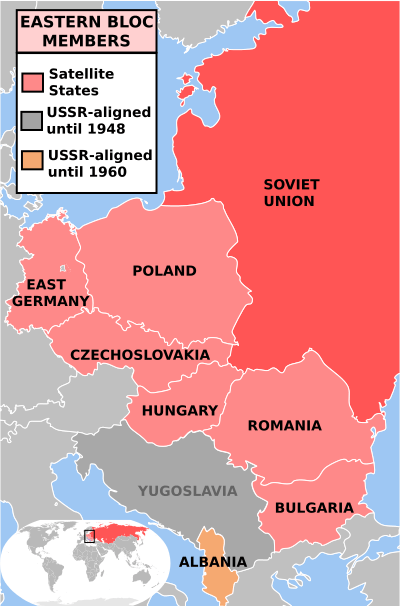

In 1980, the United States had boycotted the Summer Olympics held in Moscow in protest at the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The following 1984 Summer Olympics were due to be held in Los Angeles, California. On 8 May 1984, under Chernenko's leadership, the USSR announced its intention not to participate, citing security concerns and "chauvinistic sentiments and an anti-Soviet hysteria being whipped up in the United States".[4] The boycott was joined by 14 Eastern Bloc countries and allies, including Cuba (but not Romania). The action was widely seen as revenge for the U.S. boycott of the Moscow Games. The boycotting countries organized their own "Friendship Games" in the summer of 1984.

Death and legacy

Chernenko started smoking at the age of nine,[5] and he was always known to be a heavy smoker as an adult.[6] Long before his election as Soviet chairman he had developed emphysema and right-sided heart failure. In 1983 he had been absent from his duties for three months due to bronchitis, pleurisy and pneumonia. Historian John Lewis Gaddis describes him as "an enfeebled geriatric so zombie-like as to be beyond assessing intelligence reports, alarming or not" when he succeeded Andropov in 1984.[7]

In early 1984, Chernenko was hospitalized for over a month, but kept working by sending the Politburo notes and letters. During the summer, his doctors sent him to Kislovodsk for the mineral spas, but on the day of his arrival at the resort Chernenko's health deteriorated, and he contracted pneumonia. Chernenko did not return to the Kremlin until later in 1984. He awarded Orders to cosmonauts and writers in his office, but was unable to walk through the corridors of his office and was driven in a wheelchair.

By the end of 1984, Chernenko could hardly leave the Central Clinical Hospital, a heavily guarded facility in west Moscow, and the Politburo was affixing a facsimile of his signature to all letters, as Chernenko had done with Andropov's when he was dying. Chernenko's illness was first acknowledged publicly on 22 February 1985 during a televised election rally in Kuibyshev Borough of northeast Moscow, where the General Secretary stood as candidate for the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR, when Politburo member Viktor Grishin revealed that the General Secretary was absent in accordance with doctors' advice.[8] Two days later, in a televised scene that shocked the nation,[9] Grishin dragged the terminally ill Chernenko from his hospital bed to a ballot box to vote.[10] On 28 February 1985, Chernenko appeared once more on television to receive parliamentary credentials and read out a brief statement on his electoral victory: "the election campaign is over and now it is time to carry out the tasks set for us by the voters and the Communists who have spoken out".[8]

Emphysema and the associated lung and heart damage worsened significantly for Chernenko in the last three weeks of February 1985. According to the Chief Kremlin physician, Dr. Yevgeny I. Chazov, Chernenko had also developed both chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis of the liver.[4] On 10 March at 15:00 he fell into a coma, and died at 19:20. The autopsy showed chronic emphysema, an enlarged and damaged heart, congestive heart failure and cirrhosis.

Chernenko became the third Soviet leader to die in less than three years, and, upon being informed in the middle of the night of his death, U.S. President Ronald Reagan, who was seven months older than Chernenko and just over three years older than his predecessor Andropov, is reported to have remarked "How am I supposed to get anyplace with the Russians if they keep dying on me?"[11]

Chernenko was honored with a state funeral and was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis. He is the last person to have been interred there.

The impact of Chernenko—or the lack thereof—was evident in the way in which his death was reported in the Soviet press. Soviet newspapers carried stories about Chernenko's death and Gorbachev's selection on the same day. The papers had the same format: page 1 reported the party Central Committee session on 11 March that elected Gorbachev and printed the new leader's biography and a large photograph of him; page 2 announced the demise of Chernenko and printed his obituary.

After the death of a Soviet leader it was customary for his successors to open his safe and look in it. When Gorbachev had Chernenko's safe opened, it was found to contain a small folder of personal papers and several large bundles of money; a large amount of money was also found in his desk.[12]

Honors and awards

Chernenko was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour, 1976, in 1981 and in 1984 he was awarded Hero of the Socialist Labour: on the latter occasion, Minister of Defence Ustinov underlined his rule as an "outstanding political figure, a loyal and unwavering continuer of the cause of the great Lenin"; in 1981 he was awarded with the Bulgarian Order of Georgi Dimitrov and in 1982 he received the Lenin Prize for his "Human Rights in Soviet Society".

- Hero of Socialist Labour, three times

- Order of Lenin, four times

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour, three times

- Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945"

- Lenin Prize (1982)

- USSR State Prize (1982)

- Order of Karl Marx (East Germany)

- Order of Georgi Dimitrov (Bulgaria)

- Order of Klement Gottwald (Czechoslovakia)

Personal life

Chernenko's first marriage produced a son, Albert, who became a noted Soviet legal theorist.[13] His second wife, Anna Dmitrevna Lyubimova (1913–2010), who married him in 1944, bore him two daughters, Yelena (who worked at the Institute of Party History) and Vera (who worked at the Soviet Embassy in Washington, D.C. in the United States), and a son, Vladimir, who was a Goskino editorialist.[13]

He had a gosdacha named Sosnovka-3 in Troitse-Lykovo by the Moskva River with a private beach, while Sosnovka-1 was used by Mikhail Suslov.

Gallery

References

- ↑ "Chernenko". Collins English Dictionary.

- ↑ Jessup, John E. (1998). An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Conflict and Conflict Resolution, 1945-1996. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 121. – via Questia (subscription required)

- ↑ Hough, Jerry F. (1997). Democratization and revolution in the USSR, 1985–1991. Brookings Institution Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-8157-3748-3.

- 1 2 Altman, Lawrence K., "Succession in Moscow: A Private Life, and a Medical Case; Autopsy Discloses Several Diseases", New York Times, 25 March 1985.

- ↑ Post, Jerrold M. Leaders and Their Followers in a Dangerous World: The Psychology of Political Behavior (Psychoanalysis & Social Theory) p. 87

- ↑ Burns, John F. (16 February 1984). "World Attention Turns To Chernenko's Health". The New York Times.

- ↑ John Lewis Gaddis (2005). The Cold War: A New History. Penguin Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-1594200625.

- 1 2 Mydans, Seth (1 March 1985). "A Halting Chernenko is on TV Again". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ↑ Dmitri Volkogonov. (1998), Autopsy for an Empire: The Seven Leaders Who Built the Soviet Regime. (page 72). ISBN 0684834200

- ↑ Dvorsky, George. "Of philosopher kings and diminishing dictators". Institute for Ethics & Emerging Technologies. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ↑ Maureen Dowd, "Where's the Rest of Him?" New York Times, 18 November 1990.

- ↑ Dmitri Volkogonov. (1998), The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Empire. Harper Collins. p. 430. (ISBN 9780006388180]

- 1 2 "Prominent Russians: Konstantin Chernenko". Russiapedia. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

Sources

- Brown, Archie (April 1984). "The Soviet Succession: From Andropov to Chernenko". World Today. 40: 134–141.

- Daniels, Robert V. (20 February 1984). "The Chernenko Comeback". New Leader. 67: 3–5.

- Halstead, John (May–June 1984). "Chernenko in Office". International Perspectives: 19–21.

- Meissner, Boris (April 1985). "Soviet Policy: From Chernenko to Gorbachev". Aussenpolitik. Bonn. 36 (4): 357–375.

- Pribytkov, Victor (December 1985). "Soviet-U.S. Relations: The Selected Writings and Speeches of Konstantin U. Chernenko". American Political Science Review. 79 (4): 1277. JSTOR 1956397.

- Urban, Michael E. (1986). "From Chernenko to Gorbachev: A Repolitization of Official Soviet Discourse". Soviet Union/Union Soviétique. 13 (2): 131–161.

External links

- Human Rights in Soviet Society by Chernenko.

Quotations related to Konstantin Chernenko at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Konstantin Chernenko at Wikiquote

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Yuri Andropov |

General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union 13 February 1984 – 10 March 1985 |

Succeeded by Mikhail Gorbachev |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded by Yuri Andropov |

Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet 11 April 1984 – 10 March 1985 |

Succeeded by Andrei Gromyko |

| Sporting positions | ||

| Preceded by |

President of Organizing Committee for Summer Olympic Games 1980 |

Succeeded by |