Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon

Coordinates: 22°58′16″S 43°12′42″W / 22.971117°S 43.211718°W

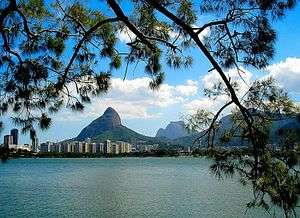

Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon (Portuguese: Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas) is a lagoon in the district of Lagoa in the Zona Sul (South Zone) area of Rio de Janeiro. The lagoon is connected to the Atlantic Ocean, allowing sea water to enter by a canal along the edge of a park locally known as Jardim de Alah.[1]

Islands

- Piraquê Island on the western edge houses the Departamento Esportivo do Clube Naval (Sport Department of the Naval Club).

- Caiçaras Island on the southern edge houses the Clube dos Caiçaras (Caiçaras Club), where water skiers tested for the 2007 Pan American Games.[2]

History

Though it receives its waters from diverse river tributaries from the surrounding hillsides, among those that stand out is the river Rio dos Macacos (today channelized), which introduces salt water. The water of the lagoon comes from the damming of an opening to the sea caused by successive build-ups of earth. This separates it from the Atlantic Ocean, except for the Canal do Jardim Alá.

Initially inhabited by the Tamoios Indians who dominated the lagoon, such as Piraguá ("Still Water") or Sacopenapan ("Path of the Herons"). The arrival of the Portuguese colonizer, Dr. António Salema (1575-1578), who was at the time also the Governor and Captain General of the Captaincy of Rio de Janeiro, intended to install a sugar mill on the banks of the lagoon. To free himself of the undesirable presence of the native Indians he spread clothes that had been worn by people sick with smallpox along the banks of the lagoon intending to kill the Indians. Such was the sugar cane plantation and the building of the Engenho d'El-Rey (The King's Mill), where today's Centro de Recepção aos Visitantes do Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro (the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden Visitors' Reception Center) operates.

These lands were once acquired by Dr. Salema from the town councilor, Amorim Soares, causing the lagoon to be called "Lagoa de Amorim Soares" (Amorim Soares Lagoon). With his expulsion from the city in 1609 the land was sold to his son-in-law, Sebastião Fagundes Varela, with the consequent name change to "Lagoa do Fagundes" (Fagundes' Lagoon). That landowner, by way of acquisition and invasion, increased the size of his landholdings in the region, in such as way that around 1620 he owned all the land from today's neighborhoods of Humaitá to Leblon.

In 1702, his great granddaughter, Petronilha Fagundes, then 35 years old, married the young Portuguese Cavalry official, Rodrigo de Freitas de Carvalho—then only 18 years old—which lends his name to the lagoon. Widower, Rodrigo de Freitas de Carvalho returned to Portugal in 1717 and died there in 1748.

The region stayed in the hands of the tenants without great fanfare until the beginning of the 19th century. Then, in 1808, the Portuguese Royal Family arrived during the transfer of the Portuguese court to Brazil. The Prince Regent appropriated the Engenho da Lagoa (Lagoon Mill) to build a powder factory and construct the Real Horto Botânico (Royal Botanical Garden)—today's Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden).

During the 19th century many diverse solutions were thought of for the problem of stagnated water—until, in 1922, the Repartição de Saneamento das Zonas Rurais (Bureau of Rural Sanitation) presented a project to "... clean up and beautify the Capital for the Independence Centennial festivities". That project involved dredging a canal to reconnect the lagoon to the sea, and deepening the land bar. The soil removed to build the canal formed the island of Caiçara, seat of today's club of the same name.

In a short time, embankments formed on its edges, which gradually reduced its surface area, providing land for the Jockey Club Brasileiro, the Jardim de Alá, and the sport seat of the Clube Naval on the island of Piraquê. The dredged channel is now called the Jardim de Alá Channel. The lagoon today represents one of the principal tourist attractions of the capital of Rio de Janeiro.

It is also known as "The Heart of Rio de Janeiro". The Lagoa neighborhood named after the Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas. It's an upper middle-class neighborhood and it has one of the largest human development indexes in the country.

Part of the lagoon is landfill that occurred in the middle of the 20th century. Many hills, such as Catacumba, Praia do Pinto, and others, occupied the area around the lagoon. For many years they housed more than fifty thousand people. However, because of poor construction quality and safety risks, after more than twenty years on the hillsides the mayor expelled all of the inhabitants and "tore down" the hills, burying a large part of the city. The inhabitants left for the suburbs and started to live in housing. Apartment buildings and parks were built in the place of the hillsides .

With 2.4 million square meters (0.93 square miles) of surface area, aquatic sports such as rowing or simply biking happen around its reflecting water. It is home to a rowing stadium (Estádio de Remo da Lagoa), a paved biking path of 7.5 kilometers (more than 4.5 miles), diverse leisure equipment, and food kiosks that offer regional and international gastronomy items. Some of the most important sports clubs in the city are by the lagoon:

- Clube de Regatas do Flamengo

- Jóquei Clube Brasileiro

- Clube Naval Piraquê na ilha do Piraquê

- Paissandu Atlético Clube

- Clube dos Caiçaras

- Club de Regatas Vasco da Gama (nautical seat)

- Botofogo de Futebol e Regatas (nautical seat)[2]

The lagoon is surrounded by the districts of Ipanema, Leblon, Gávea, Jardim Botânico, Copacabana, Botafogo, and Humaitá. It attracts quite a number of visitors during the Christmas holidays because of its famous and gigantic Christmas Tree, which is built over a floating platform that moves around the lagoon. The Eva Klabin Foundation is located on the banks of the lagoon. The lagoon will host canoe sprint and rowing events for the 2016 Summer Olympics, and rowing events for the 2016 Summer Paralympics.[3]

Pollution

The lagoon has several environmental problems, including water as well as land pollution. Currently, a private company is sponsoring a project to depollute the lagoon,[4] but this will not be quick or simple.

Though a fish colony survives along its banks, the lagoon suffers chronic fish kills caused by algae proliferation that consumes oxygen in the water. Recently, an initiative by a biologist successfully reintroduced native mangrove species and other native vegetation.[2]

There is a concern about the health risks for athletes during the 2016 Summer Olympics and 2016 Summer Paralympics. In 2015, thirteen American paddlers had stomach problems after a competition in the lagoon, which was considered a test event for the Olympics; they suffered from vomiting and diarrhea.[5] Further, it is recognized that there is not sufficient time to clean the lagoon effectively for the Olympics.[6]

References

- ↑ Alves, Maria Alice S.; Pereira, Erika F. (1998). "Richness, abundance, and seasonality of bird species in a lagoon of an urban area (Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas) of Rio De Janeiro, Brazil" (PDF). Brazilian Ornithological Society (SBO).

- 1 2 3 Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas Portuguese Wikipedia page

- ↑ Rio 2016 Bid Package (PDF). 2. Rio de Janeiro Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games. p. 18.

- ↑ Ribeiro, Patricia. "The Lagoa Limpa (Clean Lagoon) Environmental Recovery Project in Rio de Janeiro". About.com/Travel. IAC/InterActiveCorp. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Remadores dos EUA passam mal após evento-teste na Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas" [US rowers feel sick after the test event at Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas]. iG.com.br (in Portuguese). Internet Group. August 10, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Águas contaminadas são risco para atletas nas Olimpíadas do Rio" [Contaminated waters are risk for athletes at Rio Olympics]. Globo.com (in Portuguese). Grupo Globo. July 30, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

External links

-

Media related to Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas at Wikimedia Commons

_pictogram.svg.png)