Illustrated Daily News

|

The cover of the Los Angeles Daily News on November 5, 1953, just under a year before the paper ceased publication. | |

| Publisher | Manchester Boddy |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1923 |

| Political alignment | Democratic |

| Language | English |

| Ceased publication | 1954 |

The Los Angeles Daily News (originally the Los Angeles Illustrated Daily News), often referred to simply as the Daily News, was a newspaper published from 1923 to 1954. It was operated through most of its existence by Manchester Boddy. The publication has no connection with the current newspaper of the same name.

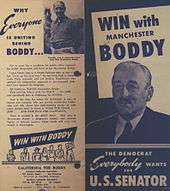

The Daily News was founded in 1923 by the young Cornelius Vanderbilt IV as the first of several newspapers he wanted to manage. After quickly going bankrupt, it was sold to Boddy, a businessman with no newspaper experience. Boddy was able to make the newspaper succeed, and it remained profitable through the 1930s and 1940s, after it took a mainstream Democratic perspective. The newspaper began a steep decline in the late 1940s and early 1950s. In 1950, Boddy ran in both the Democratic and Republican primaries for the United States Senate. Boddy finished a distant second in both primaries, and lost interest in the newspaper. He sold his interest in the paper in 1952, and publication ceased in December 1954, when the business was sold to the Chandler family, who merged it with their publication, the Los Angeles Mirror.

Founding and initial bankruptcy

The Los Angeles Illustrated Daily News was founded in 1923 by Cornelius Vanderbilt IV, who wished to start his own newspaper chain.[1] The young Vanderbilt had served as a news reporter in New York for four years, but had no experience running a paper. Believing the best newspaper was a democratic one, he offered voting rights to those who would pay $5 for a year's subscription to his newspaper.[2] Repudiating the legendary adage of William Henry Vanderbilt, "The public be damned," Vanderbilt announced that the paper's philosophy would be "The public be served."[3] Vanderbilt ignored attempts by the newspaper moguls who dominated Los Angeles journalism, William Randolph Hearst and Harry Chandler, to warn him off. Denied advertising in other newspapers, Vanderbilt attempted to gain publicity for his paper by having trucks drive through the streets bearing the paper's banner, and hiring boys to chalk the paper's name on sidewalks, much to the annoyance of landowners who had to clean it up.[3]

The paper began publication on September 3, 1923.[4] The tabloid-format newspaper was to be devoted to the ideal of clean journalism, and was prudish to an extreme: women's skirts were retouched in photos so that they would appear to cover the wearer's knees, while photos of wrestlers were altered so that they would appear to be wearing gym shirts.[1] Vanderbilt's rivals did not take well to the new competition—a graphic sex story was planted by saboteurs in the first edition, forcing Vanderbilt to stop the presses and redo page 2 before it was published. Up to a hundred Illustrated Daily News newsboys were treated at local hospitals each week after being assaulted.[5]

Unusually for the time, the newspaper covered its staff's transportation. Reporters were expected to carry rolls of nickels, so they could board streetcars and reach their assignments. However, if they had sufficient money with them, a taxicab was permitted, and Vanderbilt—"Neil" to the staff—let the staff use his two Packards to reach stories. Too often, however, the least experienced newsman on staff, Vanderbilt himself, would cover major stories. According to Rob Wagner in his history of Los Angeles newspapers of the time, Vanderbilt's "news stories reeked of naiveté and his editorials were sophomoric."[6]

By 1924, the newspaper had a good circulation but was losing money because of low advertising revenues. Vanderbilt sought help from his parents, and they agreed to help if most authority went to their hand-picked manager, Harvey Johnson. His father poured over a million dollars into the newspaper in 1924–1925, but Johnson's involvement led to a rightward shift in the newspaper, which alienated many readers. In April 1926, Johnson concluded that the Illustrated Daily News and the two other newspapers that Vanderbilt had founded in other cities could survive if $300,000 more were invested in them; however, the elder Vanderbilt refused to provide any more money. A petition for receivership was filed on May 3, 1926.[7]

Boddy takes over

A consortium of the publishers of the rivals of the Illustrated Daily News offered $150,000 to buy the paper, intending to shut it down. Los Angeles businessman Willis Lewis had invested heavily in the paper, and he put together a rival bid backed by the paper's outside shareholders, backing book publishing executive Manchester Boddy to take over the paper and keep it as a going concern.[8] The stockholder's committee got the Vanderbilt family to sign over a $1 million note so that they could top the rival bid, and raised $30,000 for a month's payroll.[9] Boddy and Lewis both served on the Commercial Board, a group of young businessmen; the new publisher got Board members to lend him $116,000 to buy a controlling interest in the paper, but if the paper did not show a profit within six months, ownership would go to the lenders.[10] Boddy once commented, "The Daily News was conceived in iniquity, born in bankruptcy, reared in panic, and refinanced every six months."[11]

The new publisher scrapped Vanderbilt's editorial policy, and began a campaign against vice. The Los Angeles police chief, James E. Davis, had a hands-off policy when it came to vice and organized crime. Most local reporters valued the perks given to them by the police, and did nothing to push the issue.[12] After Boddy began a crusade against crime and corruption, he weathered harassment by police and politicians, circulation rose, and the paper was soon showing a profit.[13] Boddy also streamlined operations and stabilized the paper's management.[14] During the first six years of Boddy's ownership, the Daily News maintained a conservative editorial policy. By 1932, Boddy had dropped the word "Illustrated" from the name of the paper. He was a personal supporter of Herbert Hoover's bid for reelection. Los Angeles newspaper owners met and decided that, with all newspaper owners supporting Hoover, one paper had to support Democratic candidate and New York governor Franklin Roosevelt, and Boddy and the Daily News volunteered for the job. The day after the election, which saw Roosevelt elected, Boddy turned to his city editor and said of the voters: "They have made a terrible mistake. I helped them do it. But damn it, I had to make a living."[15]

After Roosevelt's election, the nation waited with anticipation for the specifics of the "New Deal" plan on which he had campaigned. Boddy had no more information than anyone else, but had been impressed by a program called "Technocracy," which proposed replacing politicians with scientists and engineers possessing the technical expertise to coordinate the economy, a scheme that Roosevelt did not advocate. On November 30, 1932, the Daily News printed a huge headline "New Deal Details Bared". The article contained no inside information, and actually did not even mention Roosevelt, but instead outlined Technocracy. He continued to discuss Technocracy for weeks, as the people of Los Angeles, desperate for plausible information from any source, bought copies of the Daily News, even invading the paper's loading dock to get them as quickly as possible.[16] Even after Roosevelt took office, the Daily News trumpeted proposals to give money to the nation's citizens, such as Francis Townsend's plan that the federal government give $200 a month to every citizen over age 60. The Daily News also gave space to the "Ham 'n' Eggs" plan whereby the elderly would get checks for $30 every Thursday. Boddy hit the lecture circuit to advocate social credit, another plan for the government to return taxes to the citizenry.[17]

When the New Deal finally was revealed, Boddy became an avid supporter of it, and so did his newspaper,[18] making it the only Democratic daily in Los Angeles.[16] In 1934, writer Upton Sinclair ran for the Democratic nomination for governor, advocating the End Poverty in California (EPIC) program. When Sinclair scored a stunning upset victory in the Democratic primary against George Creel, most newspapers closed ranks against him and supported the Republican candidate, Frank Merriam. The Daily News, on the other hand, opened its front page to Sinclair's program and called him "a great man." Though the Daily News eventually endorsed Merriam, its objection was not that the program was too radical, but that it was not consistent with the New Deal. This did not stop Sinclair from being embittered at what he saw as a betrayal by the Daily News, accusing Boddy of "leading liberal movements up blind alleys and bludgeoning them."[19]

Decline and fall

Like most newspapers, the Daily News prospered during World War II. Its readership peaked in 1947, when an average 300,000 copies per day were sold. In both absolute and relative terms, however, it was falling further and further behind the other Los Angeles dailies. In addition, Boddy, who was now past sixty, was losing interest in the management of the paper. In 1950, feeling that he was repeating himself in print, Boddy sought the Democratic nomination for United States Senate.[20] Boddy was tapped to enter the race when incumbent Sheridan Downey dropped out during the primary. Democratic establishment figures distrusted the remaining major Democratic candidate, liberal Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas, and feared that a Douglas victory would hand the election to the likely Republican candidate, Representative Richard M. Nixon. Daily News staffers believed that Boddy was abandoning his journalistic integrity in running. Boddy ran in both major party primaries, a practice known as "cross filing." His campaign was ineffective, and he finished a distant second in each primary.[21] During the campaign, he dubbed the leftist Douglas as "the pink lady" in the Daily News, a nickname which was reused by the Nixon campaign in the general election.[21] Just before the primary, when Nixon, who along with Douglas had also cross-filed, sent out election materials which did not mention that he was a Republican, an ad appeared in the Daily News from the hitherto-unknown "Veterans Democratic Committee". The advertisement accused Nixon of masquerading as a Democrat, and dubbed him "Tricky Dick"—the first appearance of that Nixon moniker.[22] Nixon went on to win the general election in a landslide.[21]

After the primary defeat, Boddy went into semi-retirement, and profits from sales of the Daily News began to decrease.[23] In early 1951, he made his assistant, Robert Smith, editor of the paper.[24] In mid-1952, Boddy sold out to a consortium.[23] In August 1952, Boddy announced his retirement as publisher in Smith's favor. Smith instituted changes, scrapping the money-losing Saturday edition and started a Sunday News.[24] He called in WIlliam Townes as editor, who was well known for restoring ailing newspapers. However, Smith fired Townes after twelve weeks on the job. Smith attempted to sell the paper, and reached an agreement with a small-time Oregon newspaper owner, Sheldon F. Sackett. After signing, Smith backed out of the deal, apparently out of seller's remorse. By the time Smith finally sold the paper, in December 1952 to Congressman Clinton D. McKinnon, who was leaving office after losing a Senate primary bid, the Daily News was losing over $100,000 a month.[25] McKinnon had no better luck than anyone else in reviving the paper, and in December 1954, the paper was sold to the Chandler family, owners of the Los Angeles Mirror. Under the sale agreement, the Mirror became the Mirror & Daily News (before again being renamed the Mirror-News) and all Daily News employees lost their jobs. On December 18, 1954, publication of the Daily News ceased.[26]

According to a 1975 book about Marion Davies, the mistress of William Randolph Hearst, 51% of the Daily News was actually owned by Hearst.[27]

Notable employees

- Helen Brush Jenkins, photojournalist[28]

- E.V. Durling, columnist

- C.H. Garrigues, investigative reporter

- Matt Weinstock, columnist

Notes

An earlier newspaper called the Los Angeles Daily News was printed beginning in 1869 and continuing during the 1870s.[29]

References

Citations

- 1 2 Rosenstone 1970, p. 292.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, pp. 50–51.

- 1 2 Wagner 2000, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, p. 56.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, p. 61.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ New York Times 1967–05–14, Boddy obit.

- ↑ Rosenstone 1970, pp. 292–293.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, p. 90.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Rosenstone 1970, p. 293.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, p. 85.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, p. 86.

- 1 2 Wagner 2000, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Rosenstone 1970, p. 298.

- ↑ Rosenstone 1970, pp. 298–299.

- ↑ Rosenstone 1970, pp. 302–303.

- 1 2 3 Wagner 2000, pp. 267–269.

- ↑ Gellman 1999, p. 303.

- 1 2 Rosenstone 1970, p. 304.

- 1 2 Wagner 2000, p. 269.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, pp. 271–273.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, pp. 255–257.

- ↑ Davies 1975, p. 249.

- ↑ "Notable deaths around the nation and world as of June 23, 2013". Associated Press. OregonLive.com. 2013-06-22. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- ↑ "Los Angeles daily news". Los Angeles Public Library L2PAC Catalog. Retrieved September 2013. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)

Bibliography

- Davies, Marion (1975). The Times We Had: Life with William Randolph Hearst. New York: Bobbs-Merrill. ISBN 0-672-52112-1.

- Gellman, Irwin (1999), The Contender, The Free Press, ISBN 978-1-4165-7255-8, retrieved 2009-07-26

- Rosenstone, Robert A. (December 1970), "Manchester Boddy and the L.A. Daily News", The California Historical Society Quarterly, XLIX (4): 291–307, JSTOR 25154490

- Wagner, Rob (2000), Red Ink, White Lies: The Rise and Fall of Los Angeles Newspapers 1920–1962, Dragonflyer Press, ISBN 978-0-944933-80-0

Online sources

- "Manchester Boddy dies at 75; former Los Angeles publisher", The New York Times, New York, p. 87, 1967-05-14, retrieved 2010-07-21 (subscription required)