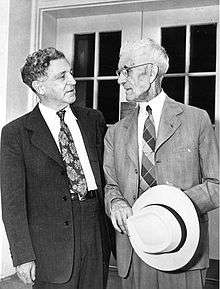

Sheridan Downey

| Sheridan Downey | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from California | |

|

In office January 3, 1939 – November 30, 1950 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas M. Storke |

| Succeeded by | Richard Nixon |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

March 11, 1884 Laramie, Wyoming |

| Died |

October 25, 1961 (aged 77) San Francisco, California |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Alma mater | University of Michigan Law School |

Sheridan Downey (March 11, 1884 – October 25, 1961) was a lawyer and a Democratic U.S. Senator from California from 1939 to 1951.

Early life

He was born in Laramie, the seat of Albany County in southern Wyoming, the son of the former Evangeline Victoria Owen and Stephen Wheeler Downey. He was educated in public schools and graduated from the University of Wyoming in Laramie in 1907, and from the University of Michigan Law School in Ann Arbor. He subsequently returned to Laramie to practice law, and in 1908 he was elected district attorney of Albany County as a Republican. In 1910 he married Helen Symons; they had five children. In 1912, Downey split Wyoming's Republican vote by heading the state's "Bull Moose" revolt in support of Theodore Roosevelt, thus leading to a Democratic victory statewide.

Politics

In 1913, Downey moved to Sacramento, California, and continued to practice law with his brother, Stephen Wheeler Downey, Jr. During his first few years in California, he devoted most of his time and energy to his law practice and various real estate interests. In 1924 he supported Robert La Follette, Sr.'s Progressive party campaign for the presidency, and in 1932 he became a Democrat and campaigned for the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In October 1933, Downey announced that he was running for governor of California, but after a series of meetings with the writer Upton Sinclair, who also had designs on the governorship, Downey agreed to run for Lieutenant Governor of California as Sinclair's running mate, stumping on the End Poverty in California (EPIC) plan (opponents called the ticket "Uppie and Downey"). EPIC began as a mass movement, calling for an economic revolution to lift California out of the depression. The EPIC platform called for state support for the creation of jobs, a massive program of public works, and an extensive system of state-sponsored pensions and radical changes in the tax structure.

Before long, more than 2,000 grassroots EPIC clubs sprouted throughout the state, and the most popular EPIC anthem, "Campaign Chorus for Downey and Sinclair," was made into a phonograph record by Titan Records for mass distribution. It featured the speaking voice of Downey, announcer Jerry Wilford, and the singing of three men calling themselves the "Epic Trio." While EPIC was defeated by Republican Frank Merriam in November 1934, Downey, who had been subjected to less vitriol than Sinclair during the campaign, remained a viable political force in the state. Downey actually garnered 123,000 votes more than his running mate, and he gained a statewide reputation as a champion of progressive politics.

After Sinclair's defeat, Downey became an attorney involved with Dr. Francis Townsend, the main advocate of the Townsend Plan for government old-age pensions. Townsend's $200-a-month pension plan had won a large following in California, particularly among retirees. In 1936, the two drifted apart, as Townsend supported Union Party presidential nominee William Lemke of North Dakota, and Downey remained a Democrat committed to Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

U.S. Senate

In 1938, Downey ran for the U.S. Senate as a supporter of the proposed "Ham and Eggs" government pension program. He defeated incumbent Senator William Gibbs McAdoo, the former son-in-law of Woodrow Wilson, in the Democratic primary by more than 135,000 votes. Despite the strong backing McAdoo received from the White House and a personal campaign appearance by President Franklin Roosevelt to endorse the incumbent, Downey won the primary and went on to victory in November, defeating Republican Philip Bancroft by a 54-46 percent margin. During the 1938 campaign, Downey appeared on the cover of Time.

Though he had been considered a staunch liberal, Downey as a senator became a conservative Democrat who won the support of California's major oil interests. He supported the efforts of oil companies and agribusiness to procure state, rather than federal, control of California's oil resources. He also worked to exempt the California Central Valley from the Reclamation Act of 1902, an action which assisted corporate farms.[1] In the Senate, Downey also introduced a series of pension bills, and in 1941 he was named chairman of a special Senate committee on old-age insurance. He took an early stand supporting a military draft but opposed the Roosevelt administration's plans to requisition industries in time of war. During World War II he called for the creation of a committee to investigate the status of blacks and other minorities in the armed forces and advocated a postwar United Nations, international control of atomic energy, increased veterans' benefits, and federal pay raises. At the end of the war he opposed continuation of the military draft. During his years in the U.S. Senate Downey often represented the interests of California's powerful motion picture industry. His shift from a liberal New Dealer to a conservative Democrat would become officially recognized after the war ended.[2]

Re-election

After his narrow reelection to the Senate in 1944, defeating Republican Lieutenant Governor Frederick F. Houser by 52 percent to 48 percent, Downey began a push for the California Central Valley project, which had been initiated during the 1930s as part of the New Deal's vast array of public works projects, such as power dams and irrigation canals.

In a 1947 book entitled They Would Rule the Valley, Downey argued that the farmers of the Central Valley, who controlled water rights based on state law, would come into conflict with the federal Bureau of Reclamation. Downey acknowledged that Central Valley farmers were technically in violation of the Reclamation Act of 1902, but defended these violations of Federal law as necessary because, in the context of California agriculture the Federal limitation was impractical.[3] Downey's political views made him vulnerable. Helen Gahagan Douglas challenged him in a primary. 1950 Downey dropped out of the race, citing ill health, and threw his support in the Democratic primary behind Manchester Boddy, the conservative and wealthy publisher of the Los Angeles Daily News. He even indicated that if Douglas won the primary, which she did, he would support Republican U.S. Representative Richard Nixon in the general election. In the ensuing Douglas-Nixon race, Nixon prevailed in what his critics called a smear campaign. From this race, Nixon emerged with the sobriquet "Tricky Dick".[4]

Later life and achievements

After he left the Senate, Downey practiced law in Washington, D.C., until his death in San Francisco in 1961. Downey also served as a lobbyist representing the city of Long Beach and the large petroleum concerns leasing its extensive waterfront. Upon his passing, he donated his body to the University of California Medical Center in San Francisco. His papers are archived at the Bancroft Library in Berkeley.

During his years in the Senate Downey was often described as slight, grayish, and strikingly handsome. His political career in many ways typified the transformation of millions of Republican progressives who supported Theodore Roosevelt and the "Bull Moose" movement of 1912 into Democratic supporters of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal in the 1930s. During the 1930s and early 1940s Downey was one of California's most significant progressive politicians. While he was often overshadowed in state politics by Republican progressives like Hiram Johnson and Earl Warren, Downey left a significant mark because of his tireless advocacy of old-age pensions, organized labor, and racial justice. His conservative turn after his reelection in 1944, when he increasingly represented the interests of big business, large agribusiness concerns, and the oil industry, has obscured his historical reputation as a one-time liberal and progressive force in California politics.

- United States Congress. "Sheridan Downey (id: D000469)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

Works

- Onward America, 1933.

- Courage America, 1933.

- Why I Believe in the Townsend Plan, 1936.

- Pensions or Penury?, 1939. - An early book of New Deal advocacy.

- Highways to Prosperity, 1940.

- They Would Rule the Valley, 1947. - A book written to inform Californians about the Federal Government's efforts to impose undue economic restrictions on agriculture via the Reclamation Bureau.

References

- Congressional Biographical Directory: Sheridan Downey - From the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Guide to the Sheridan Downey Papers from 1929 to 1961 - Provided by the Online Archive of California and Bancroft Library.

- http://politicalgraveyard.com/bio/down-downey.html

- ↑ Kenneth Franklin Kurz, Nixon's Enemies, NTC/Contemporary Publishing Group, 1998, p. 102

- ↑ G. J. Barker-Benfield, Catherine Clinton, Portraits of American Women: From Settlement to the Present, Oxford University, 1998, pg. 554, https://books.google.com/books?id=HemsBuz3kqkC&pg=PA555&lpg=PA555&dq=sheridan+downey+became+conservative&source=bl&ots=8wc0h0Kq9g&sig=UmvM8Ks6wQd_P1RvsvgRO_BB1bw&hl=en&sa=X&ei=ggDUT6PWOcG-2gWOzpSGDw&ved=0CFoQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=sheridan%20downey%20became%20conservative&f=false

- ↑ Downey, Sheridan. 1947. They Would Rule the Valley San Francisco, self published

- ↑ Kenneth Franklin Kurz, Nixon's Enemies, NTC/Contemporary Publishing Group, 1998, p. 103

External links

| United States Senate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Thomas Storke |

U.S. Senator (Class 3) from California January 3, 1939 – November 30, 1950 Served alongside: Hiram Johnson, William Knowland |

Succeeded by Richard Nixon |